Photographers capture the human stories behind 70 years of refugee crises

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Moises Saman (banner) / Magnum Photos (all images)

A young girl is staring longingly in to the distance as she waits patiently for milk to be distributed at a refugee camp in Northern Greece. The young children around her have dust stuck to their faces and carry the same weary, concerned expressions, testament to the arduous ordeal they’ve been through since being forced to flee their homes.

Refugees from the civil war areas. Waiting for this unfamiliar stuff, UNICEF milk (reconstituted from powdered milk) distributed for the first time at the refugee camp. Ioannina, Greece 1948 © David Seymour (Chim)

This could be today, in any of the refugee camps that have sprung up across Greece to house thousands of families who have crossed the Mediterranean in flimsy boats from Turkey to find safety. But the striking black and white is a clue that the image dates from much earlier. In fact, it was taken at the Ioannina camp in 1948, nearly seven decades years go, by David ‘Chim’ Seymour, one of the co-founders of celebrated photography agency Magnum.

I Welcome is an exhibition created by Amnesty International and Magnum Photos, which explores how the agency’s photographers have documented refugee crises since the agency’s founding in 1947. With access to Magnum’s immense archive covering the past 70 years, it connects past and present, from the mass displacement of peoples across Europe after World War II to the Vietnam war, Chechnya and our present day refugee crisis, which sees people fleeing primarily from Afghanistan, the Middle East and North Africa.

It explores the deep personal motivations of the nearly 20 Magnum photographers who have documented these mass flows of people: empathy and a search for understanding of the many factors, from conflict to drought and disease, that force people to leave their homes around the globe. But as part of Amnesty’s broader I Welcome campaign, it also puts our contemporary political response in its historical context and calls on the UK and other wealthy governments to bear their share of responsibility in responding to today’s refugee crisis.

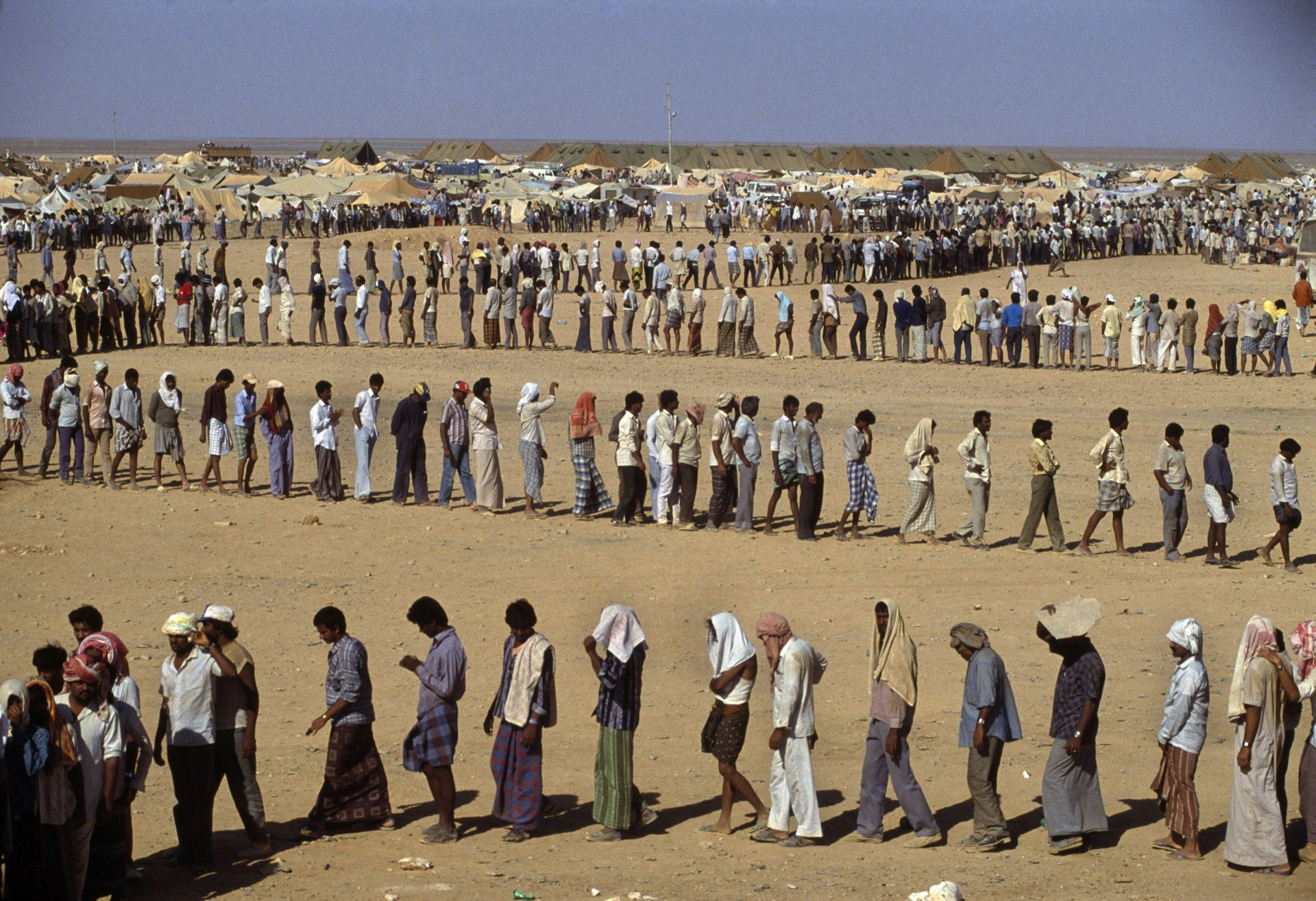

Refugees In the desert. The Sha-alaan One camp, is the worst camp. They have orderly food lines with thousands of refugees waiting calmly for food distribution from the CHARITAS charity organization. Jordan,1990 © Chris Steele-Perkins

“Magnum’s founders came together creatively, partly in response to what was happening in the news media: forming the agency to allow them to work outside the traditional framework of magazine journalism and ensuring that the copyright to their images was held by the authors of the imagery, not by the magazines that published the work,” explains Emily Graham, Magnum’s Cultural Projects Manager. “But it was also a response to the experience of WWII, which affected all of our founders and inspired a move to towards a far more humanitarian approach to looking at the world.”

“Magnum’s relationship to the coverage of the movement of displaced people really does stretch back to those founding years,” she continues. “Our photographers were present throughout and were committed to bearing witness. David ‘Chim’ Seymour, for example, carried out one of the first large charity commissions for UNICEF, called Children of Europe, surveying the situation for young people in the aftermath of WWII.”

Five boys from Promahi in front if the refugee ship S.S Samos that evacuated children during the Civil War. Greece, 1948 © David Seymour

Chechen refugees living in neighbouring Ingushetia. RUSSIA. Ingushetia, 11/12 1999. © Thomas Dworzak

Seymour was famous for his empathy towards his subjects and he helped set the mould for the involved, compassionate post-war photojournalist. His influence over the development of Magnum was significant, after he founded the agency with Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and William Vandivert (all photographers), as well as Rita Vandivert and Maria Eisner.

The refugee is as old as history itself, and since the agency’s founding, there have been continual conflicts and crises that have produced new exoduses of peoples across the globe. Magnum’s photographers have set their work apart from others through the personal artistic response they’ve brought to the work, but perhaps even more importantly, their commitment to documenting every stage of the process: investigating why people are forced to flee, documenting their journeys, time spent in limbo at refugee camps, and their situation when they finally arrive in places of stability and security.

The battle for Saigon. Refugees under fire. Confused urban warfare was such that Americans were shooting their staunchest supporters. VIETNAM, 1968. © Philip Jones Griffiths

The drive to create awareness around migration is driven by an understanding of how awareness can create change – an improve the lives of those displaced. While the Spanish Civil War (which Capa documented) was raging, in 1937 the Basque government asked British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to take in child refugees to protect them from Franco’s bombs. He denied the request, until popular pressure (buoyed by news coverage) forced a rethink and he eventually agreed to accept 4,000 unaccompanied children. Public consciousness and pressure has always been necessary to force governments to live up to their responsibilities when it comes to supporting refugees, from the Hungarian refugees who fled Soviet occupation in 1956, to victims of the Balkan conflicts in the ‘90s – and remains so today.

But as budgets have fallen and much of the media contributes to a hostile atmosphere towards refugees, Magnum have been forced to change tactics to ensure migration receives continued and thoughtful coverage that contributes to understanding, rather than fuelling fear or inflating negative stereotypes.

Isikveren Camp. Kurdish fleeing northern Iraq arrive at the refugee camp. Over 250.000 Kurds fled from Iraq after a bitter counter attack by Saddam HUSSEIN in northern Iraq. They now live in the mountains on the Turkish border. TURKEY. Uludere. 1991 © Bruno Barbey

Stenkovac. Refugee camp. Macedonia,1999 © Cristina Garcia Rodero

“The flow of images online means its more difficult to get people’s attention,” Emily explains. “Empathy does require engagement. We’ve been thinking about how to convey complex issues to people in the hope that they engage.” The agency has self-funded a comprehensive project to document the current refugee crisis, despatching its photographers to record destruction and civil conflict in Syria, perilous journey across borders, life in refugees camps and efforts to integrate, in countries like Germany, for example.

A family stands on what is left of their home. SYRIA. Kobani / Kobane (Arabic: Ayn al Arab). 06 August 2015. © Lorenzo Meloni

Yet despite the amazing work produced, not solely by Magnum photographers, many governments across Europe and the US seem to be more concerned with attempting to pull up the drawbridge than offering support to refugees. Partnering with Amnesty, and presenting an exhibition that emphasises the similarities and continuities of the many refugee crises since WWII, is a conscious effort to provoke the necessary response to support displaced people. Presenting the exhibition free to public, in the open air, on London’s South Bank is a way of reaching the greatest range of people, many of whom may not experience the work any other way.

Syrian families, mostly from Aleppo, are placed in a refugee camp in Vasariste near the Serbian- Hungarian border. After a day to recover, they will walk and attempt to cross the Serbian-Hungarian border to get to Serbia, the last country that stands between them and a European Union member state, Hungary. SERBIA. Vasariste. August 12, 2015 © Jerome Sessini

But for Magnum’s photographers, the most powerful way to document an issue or help lay the groundwork for change has always been to do what its photographers do best: focus on human stories.

“I think what really comes across in the exhibition is this idea of the similarities rather than differences of people all over the world, regardless of their vastly different contexts,” Emily explains. “Photographers have attempted to tell the human story behind migration, rather than other-ing the people in the photographs. The goal is to tell stories of people in challenging situations by putting the people at the forefront of those stories.”

I Welcome an Amnesty International and Magnum Photos exhibition of photographs of refugee crises past and present is on display at London’s Southbank, between Gabriel’s Wharf and the National Theatre, until Sunday 18 December.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.