The photojournalist who braved prison and a hunger strike

- Text by Mathias Depardon, as told to Andrea Kurland

- Photography by Mathias Depardon

Shortly before I was released from prison, my counsel turned to me and said, “There are a lot of people outside waiting to hear from you. You better start drinking some sugar.” I’d been locked in a room for the past 30 days, on hunger strike for six. But the week that followed my release was somehow worse.

Every photographer who works in Turkey knows the country has changed, that the job carries risks. The first time I was detained was in January after police at Gaziantep airport found photos of Kurdish PKK soldiers on my Instagram and accused me of producing ‘terrorism propaganda.’ From that point on, my name was marked and my press pass renewal stalled. I told the authorities that I would continue working throughout the renewal process. And in May, I travelled to the southeast to document the construction of water dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers for National Geographic. Tensions over water have long haunted the Middle East, with Turkey being accused of hoarding supplies and fuelling conflict in Syria and Iraq. It’s a story I wanted to explore, starting with Turkey’s dams.

View of the town of Hasankeyf above the Tigris River. The Ilisu dam project will flood 80 per cent of its ancient monuments, along with 52 other villages and 15 small towns, by 2018.

On 8 May, I was returning from a dam when I was stopped by local police. They asked to see my photographs but, shooting on a Mamiya 7 camera, I couldn’t show them what was on film. They accused me of spying. Within 24 hours, I was in a detention centre 300km away. For the first week I was placed in isolation on the same floor as illegal migrants; the top floor was reserved for ISIS. But because I was isolated – and a Westerner – the other detainees and guards assumed I was a jihadist.

Life on the inside is a psychological rollercoaster. You wake up every day and nothing has changed. You know your case has become political – things happened on a diplomatic level that were over my head – but you don’t get much information. You leave your room for 15 minutes a day. You speak to a lawyer twice a week for 10 minutes. Every time you hear a set of keys, or a car, you think it could be for you. You don’t know if you’ll be there for hours, days or months. You try to set your mind to the longer term. And obviously, all you do is read. It’s the only kind of metaphysical escape you have.

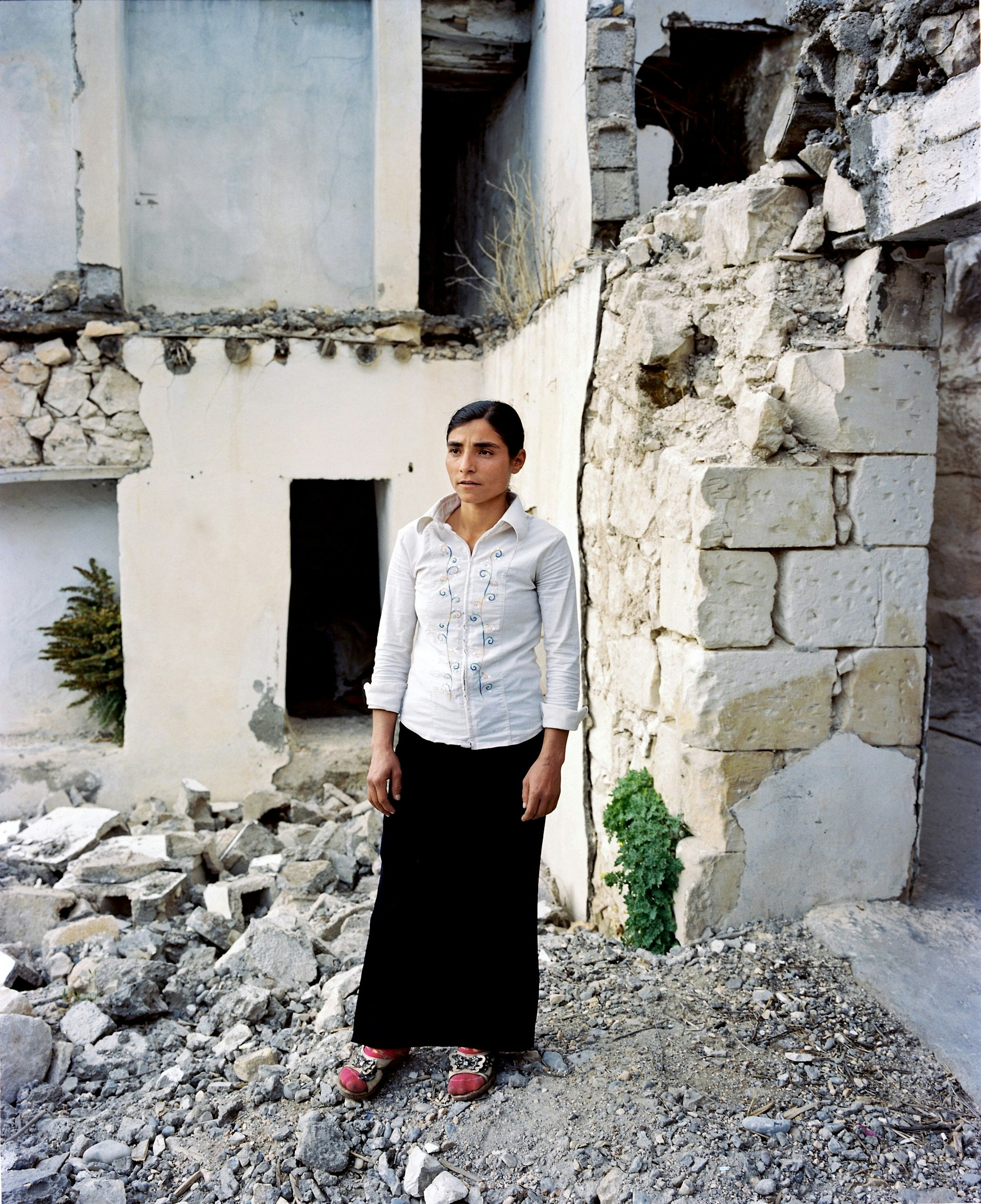

A woman stands in the ruins of the flooded village of Savaçan, facing the reservoir lake of the Birecik Dam on the Euphrates River.

On 21 May, I stopped eating. When you’re in this position, you can’t do anything but wait – and this was a way to take back some control. Thankfully, it provoked authorities to elevate my case. On 25 May, my president, Emmanuel Macron, met with Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at NATO. I was released two weeks later.

As much as I feared being detained, ultimately you’re in a safe environment. It was just a matter of bearing through it. The toxic part came after my release.

A man repaints the bridge crossing the Tigris River.

You spend five weeks in prison and the next day you’re in Paris starting a new life. I wasn’t at ease with the outside world and stayed in my hotel room for days, feeling claustrophobic and slightly schizophrenic. My phone exploded in my face with messages and media requests. We live in a world where everyone wants a million followers, but real fame must be hell. When everyone knows your story, and they all want a piece of you, it’s a living nightmare.

I realised I was spinning out when I was alone for the first time. People kept saying, ‘Have you seen a shrink?’ and of course I said I was fine. But honestly, I haven’t brought my life back on to my own terms – and I haven’t taken a photograph since.

A man pauses on his motorbike near the Keban dam on the Euphrates River, Anatolia.

I think I had anger within myself before all this, but it’s really coming out now. What I’m describing, I guess, is a burn-out. I need to make decisions in my life – both within my photography and my relationships. They’re all decisions I could have postponed but suddenly I cannot buy any more time.

It’s hard to explain how and why this is happening. We all live our lives within our choices. But when people see you as this experience, you feel you have to start new somehow. It’s like a page is turning and everything behind it needs to be confronted. It’s a great way to restart your life – to flatten things that have been tense. To re-seek those dynamics that made you do what you do, and that used to bring you joy.

A beekeeper near the town of Halfeti, Turkey, where a flood displaced over 6,000 people in 2000.

Buy a limited-edition print by Mathias Depardon from our printshop, or see his work in Rule-Breakers: The Exhibition, showing at 71a London until December 22.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.