John Loengard on sixty years shooting the most famous faces of our time

- Text by Noora Ismail

- Photography by John Loengard

To become a master in your field it’s always good to start out young, whether you’re an acrobat, a chess-player, or a musical prodigy. The same can be said for photographers too: many of the greatest began shooting in their youth, just like John Loengard.

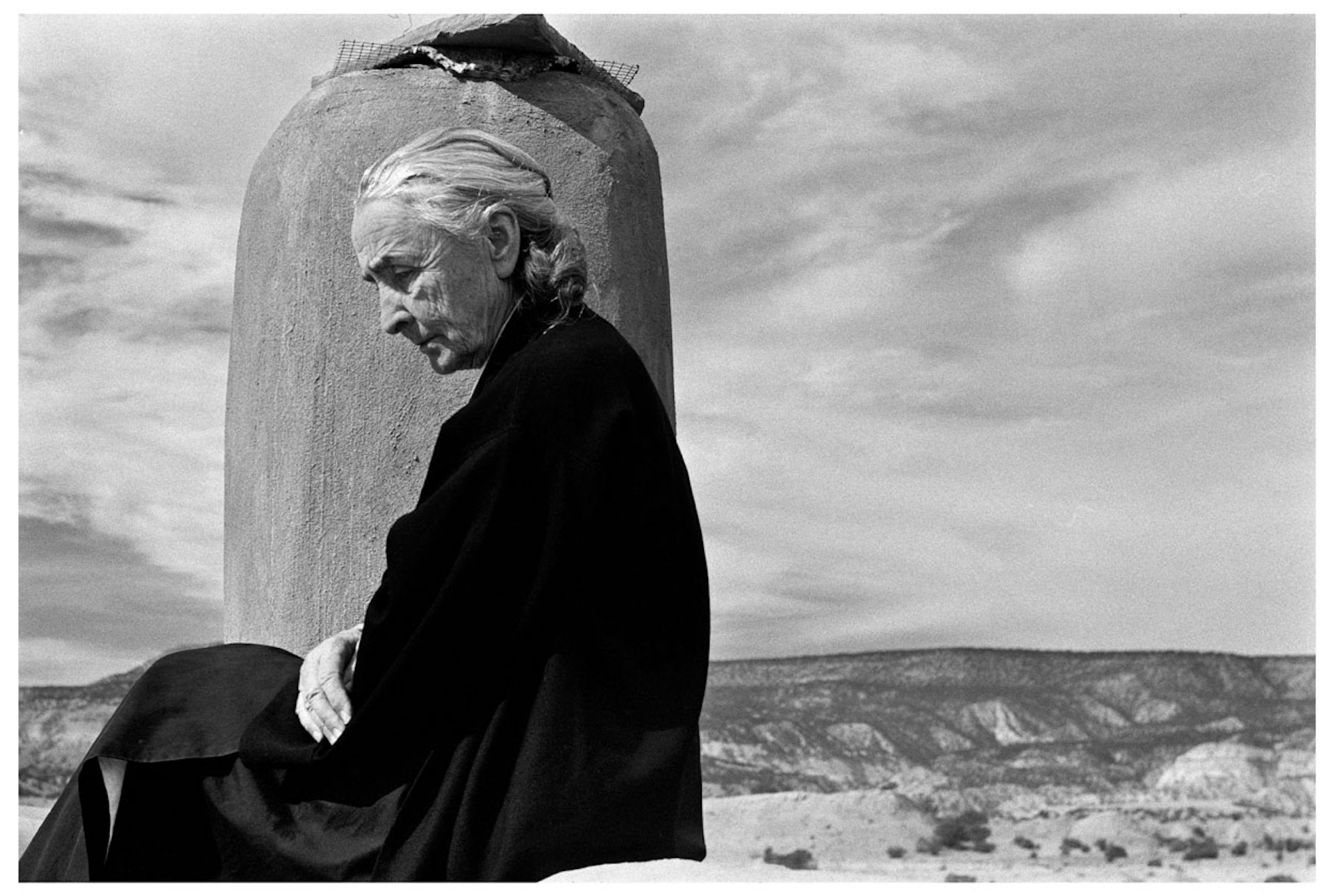

Best known for his work for Life Magazine, Loengard began developing his craft at the tender age of 11. By the time he reached Harvard he was already shooting some of the world’s most famous faces for titles nationwide. From Ronald Reagan to Georgia O’Keefe, Marilyn Monroe to The Beatles, Loengard has immortalised the faces of a generation.

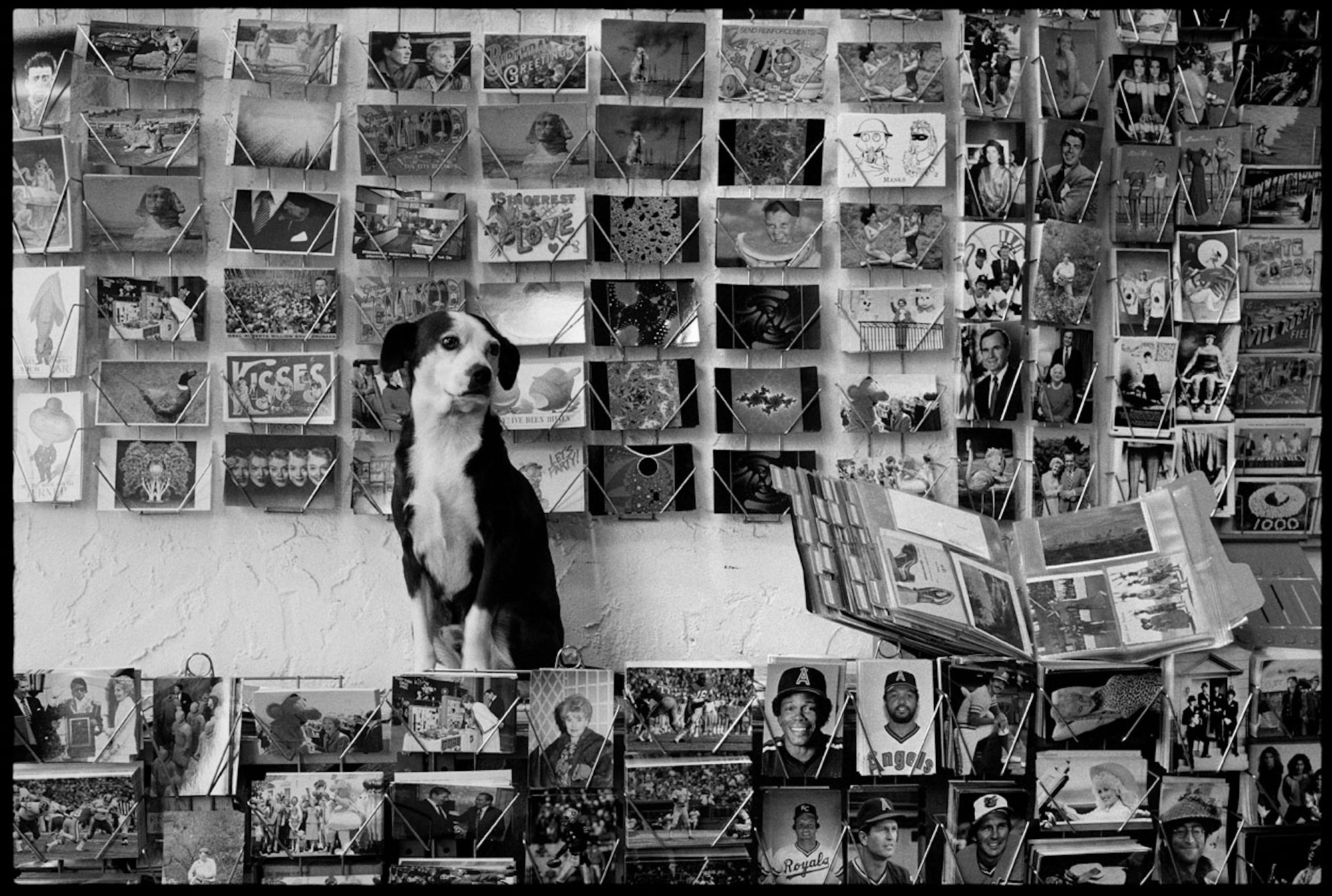

In his latest book, Moment by Moment, Loengrard weaves together his favourite images not just of celebrities and photographers, but his family too. “A great photographer has the knack of putting a great picture in front of his camera”, he once said. It’s a mantra that’s visible in this collection.

You’ve shot some of the most famous people in the world, who were your favourites?

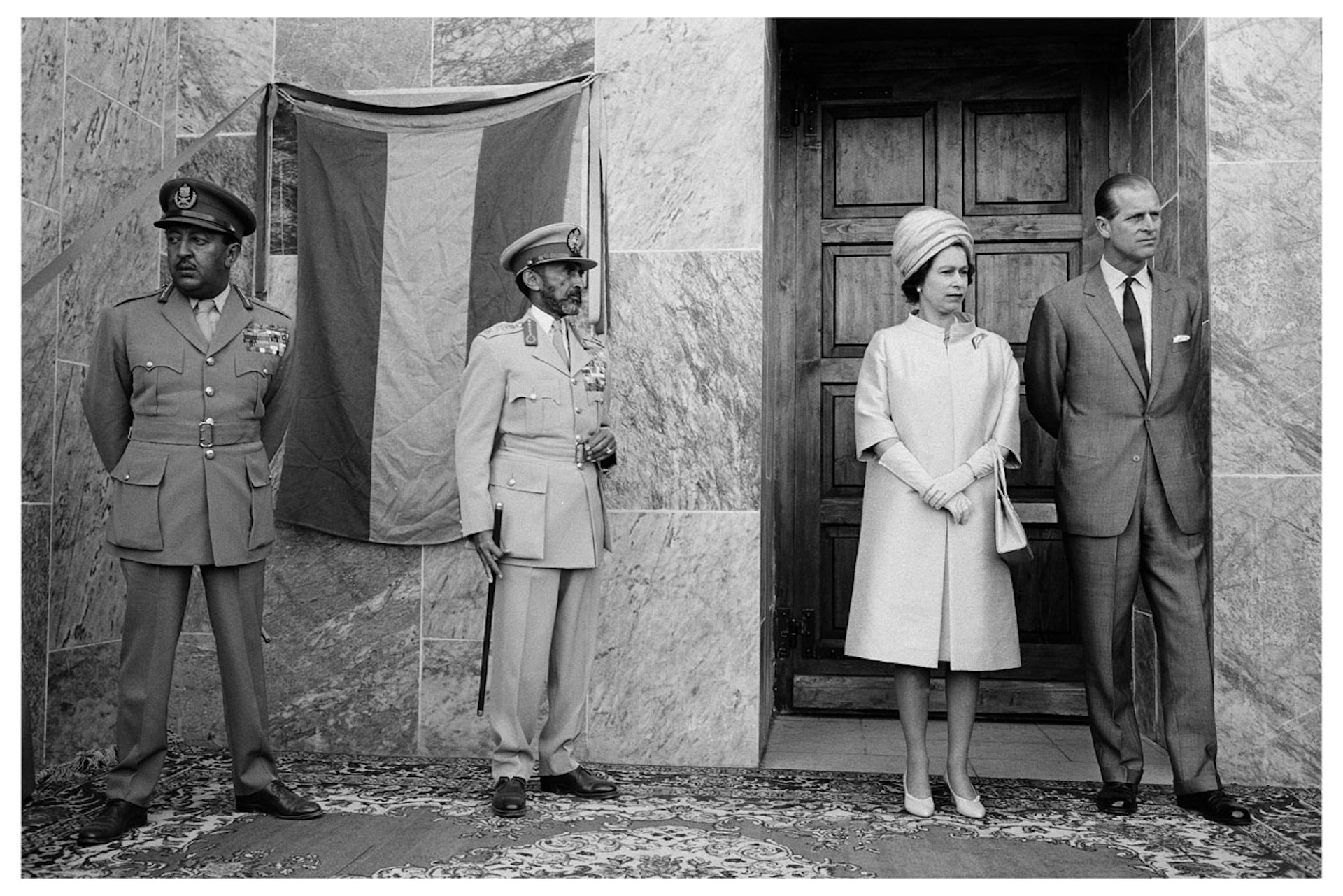

How famous do you have to be? It’s always interesting to meet someone you’ve heard a lot about, but if they are in power, conditions can be very restrictive.

In the case of the Queen of England, the Palace keeps the press behind a very strict line, and there is very little original you can do with ten colleagues to your left and ten to the right snapping away. Sometimes something might slip through, as I feel it did when the Queen toured Ethiopia, but it’s not how I’d like to work. On the other hand, if writer John Updike is famous enough then, heck, we spent a congenial hour driving around Beverley, Massachusetts. I enjoyed our chatter, and I’d be happy to spend another hour with him.

What is your favourite portrait in Moment by Moment that you have taken and why?

I’m sorry. I don’t play favourites. I also don’t believe anecdotes. I’ve become skeptical enough of words so as to distrust those neat, clever stories—because much of my life has been spent separating what can be said from what I can see.

Why did you decide to include portraits of your family in the book?

I feel that if I photograph other people’s children, I should photograph my own by the same standard.

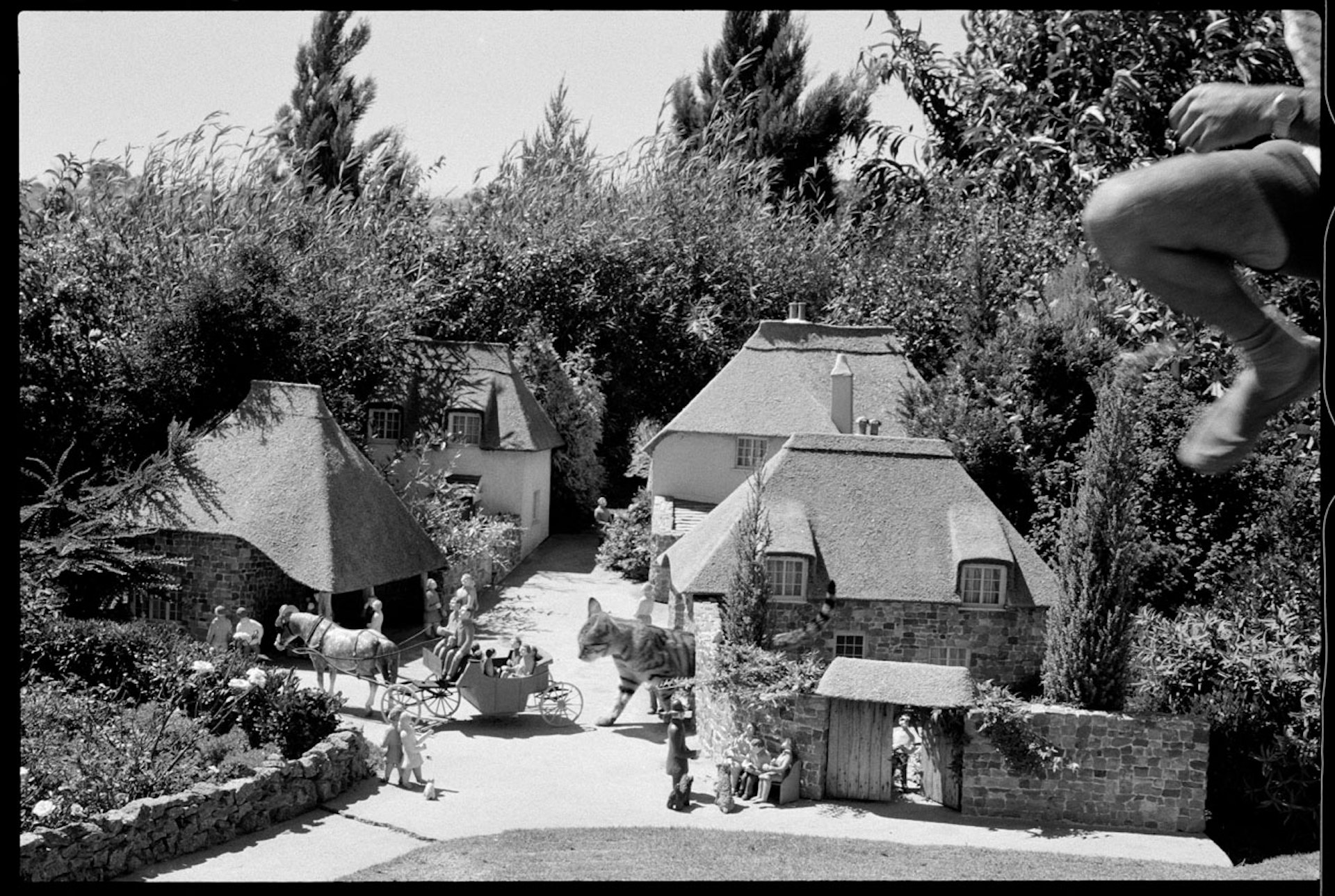

When places together, some of your pictures highlight the stark inequality in 1960’s Britain. Was this your intention?

I went to England in 1968, nearly fifty years ago. I used the trip to take pictures of what might then have been the most photogenic population in the world. There were still a plethora of codes of dress and manner that signified class and status and wealth. Although it was less obvious than the costumes August Sanders dealt with in Germany, in the nineteen twenties and thirties, it was present.

As I was taking photographs I did not plan one picture to work against another. But I did go to Manchester to photograph a city in decay, and I went to Eton to look at schoolboys being educated in the shadow of Windsor Castle. They fit together in their contrast, but I can’t say this was because a precise plan fingered these lads.

You have said in previous interviews that composition is more important than lighting in your photography.

Almost always. I take pictures on sunny days, both indoors and out. Obviously, that limits what I can do. On cloudy days I could work from any side of the subject. Why limit myself? I do so, for one thing, because light and shadow make a subject seem solid. I am trying to turn reality into a picture by slipping a two-dimensional rectangle out of a three dimensional world. A feeling of depth, of space, seems useful.

Beyond that, I want my slice from life to be expressive. Expression—the picture’s balance, its surprise, its clarity, its energy—depends on its composition. What do I see and how do I see it? Of course that’s most important.

What about the relationship you have with your subjects?

I don’t develop a relationship with my subjects. Neither does the guy from the cable company when he hooks up my TV. I think my subjects believe I know what I’m doing and that I do it well. And actually what I’m doing is noticing them. We all like to be noticed as we pass through life.

I want to take pictures of people as they are doing things that they do often. I can interrupt easily to say do that again or can you do that over here? They understand that I’m trying to make a good picture of them, and anything I suggest is to make that picture better.

My interest is flattering, I think. And somewhere in this process, their concern about being photographed drops away for a moment and a natural, unguarded expression appears, not only on the face. It is also in the shoulders and the knees and the hands, all through the body. It is peculiar and particular to the person.

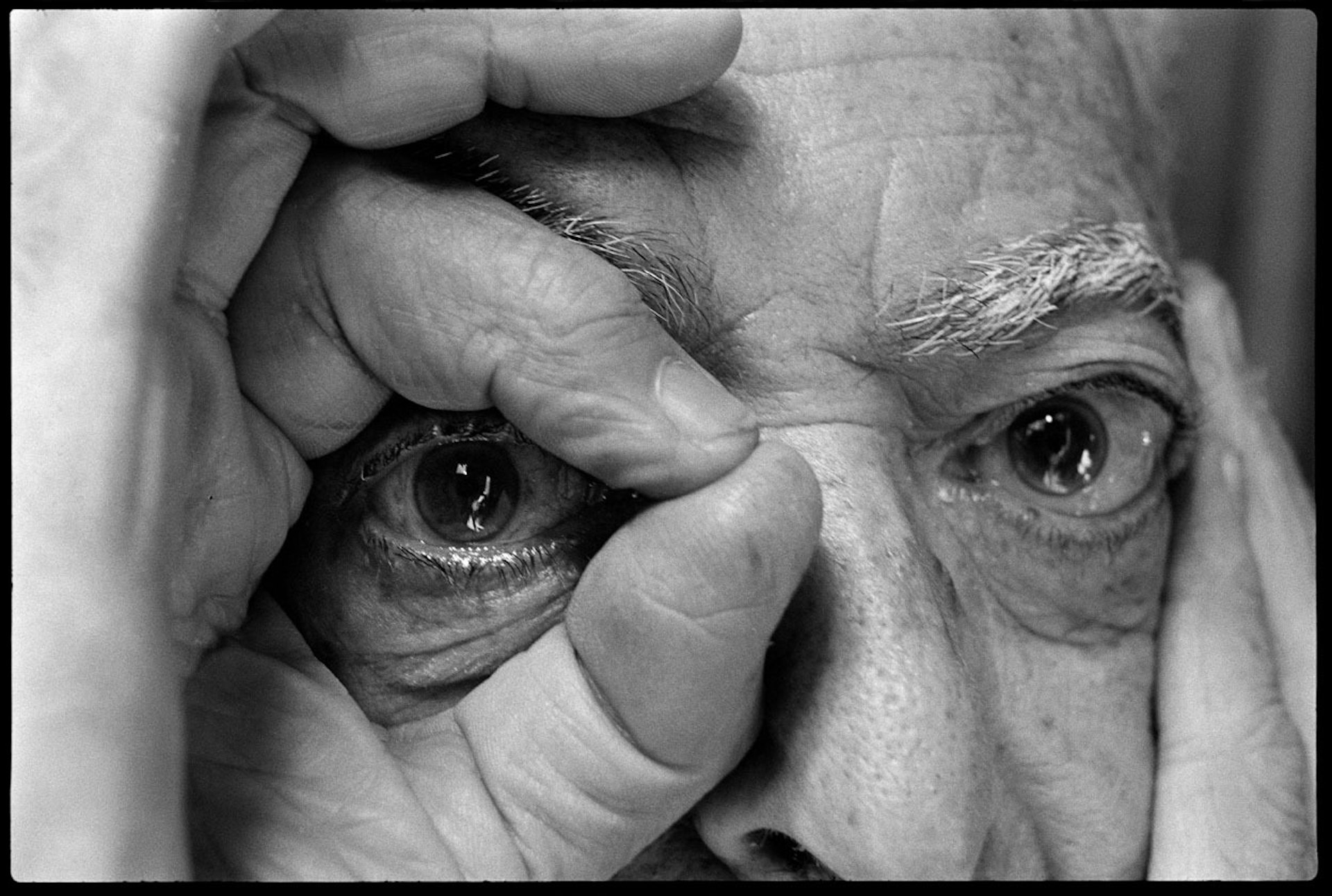

I’ve always found photographers easy to photograph, probably because they so rarely are. However, I found one of them quite difficult. I photographed André Kértesz, on two days, in his home and at his printer’s lab. Looking at my contacts, I felt that using my camera was like pounding a piece of rubber with a hammer. I caught nothing remotely telling. On the other hand, Brassai, for example was a piece of cake. So was Annie Leibovitz. Everything works. Who knows?

What challenges did you face in the curation process for this book?

Putting a book of photographs together is difficult, I am very pleased with the way this one turned out, but it suddenly came together after five years of fiddling. It’s never the pictures left out that are a problem, it’s what is put in.

Moment by Moment is published by Thames & Hudson.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.