The photographer who shot Britain’s Black Panthers

- Text by Natty Kasambala

- Photography by Neil Kenlock

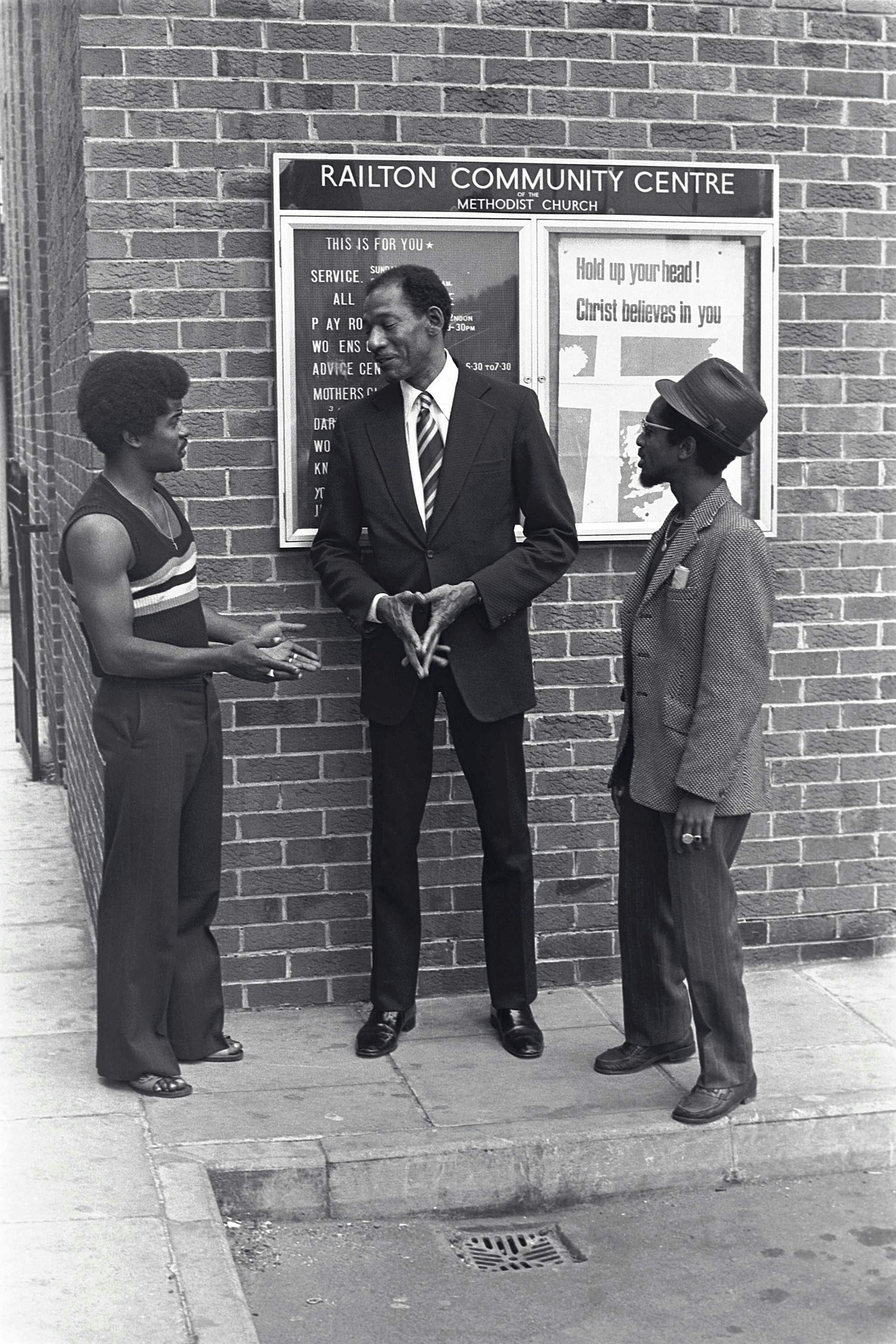

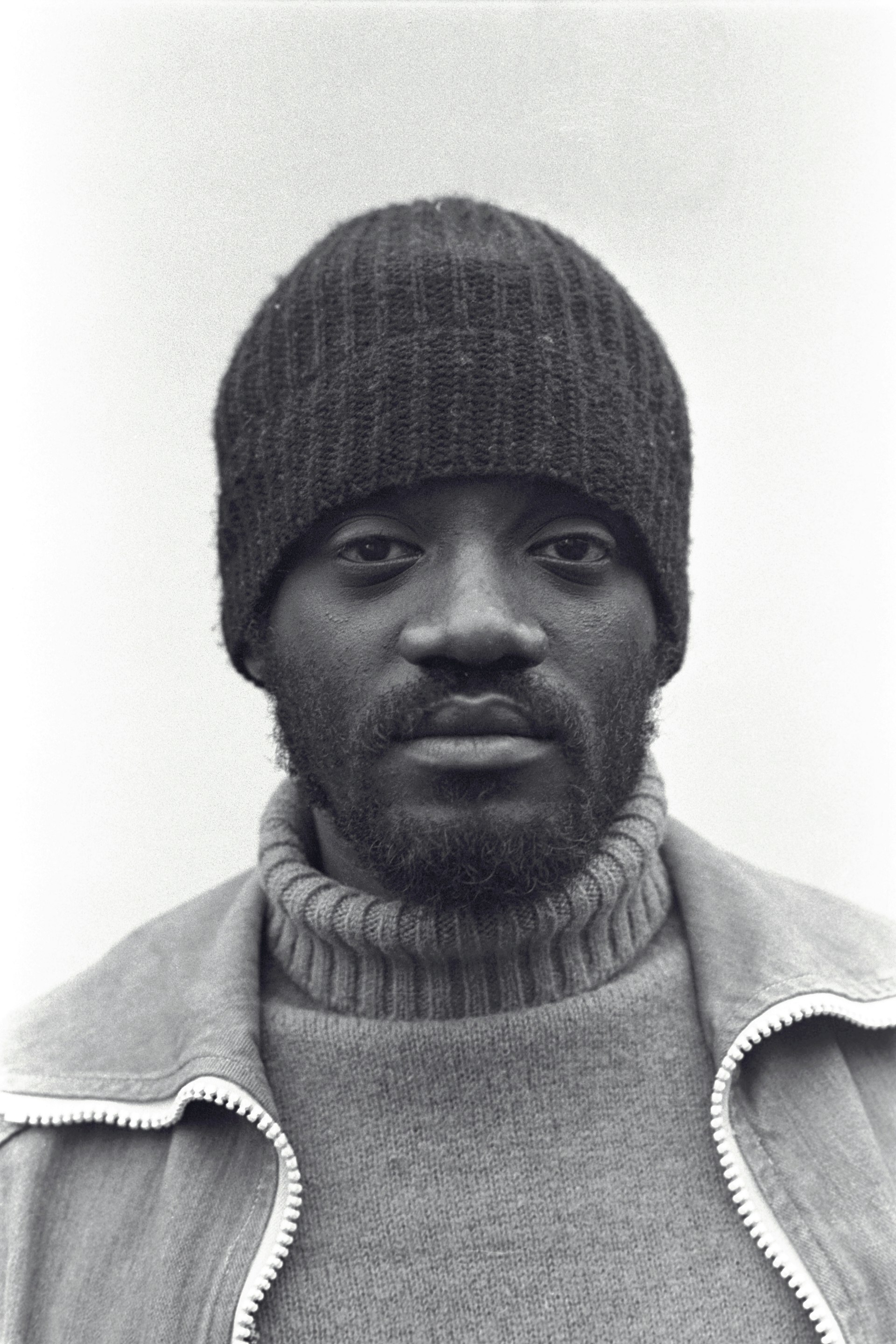

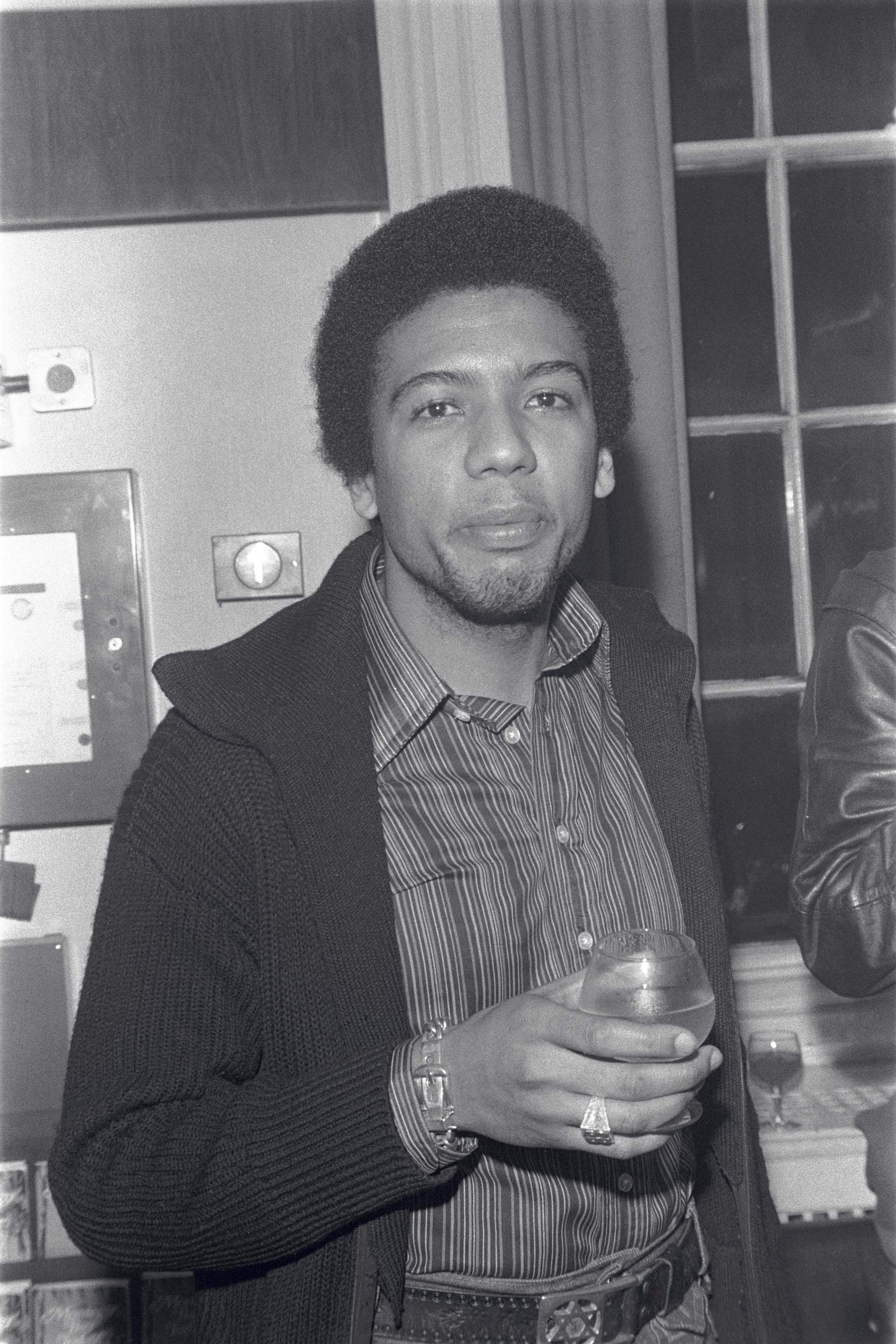

Neil Kenlock’s portraits of black Britons during the ’60s and ’70s were a stark contrast to the passive, personality-free depictions that had come before. Instead, his subjects were central, bold, and unafraid to meet your eye.

The London photographer was primarily determined with battling the constant challenges of discrimination, and his goal was to champion those without a voice.

He did so the best way he knew how: storytelling. Inspired by the Black Panther movement in the States – and enticed by a canvasser in Brixton for their British equivalent – Kenlock attended one meeting and left as the official photographer of the British Black Panthers movement.

“America was our inspiration,” he recalls. “We read their books and tried to follow their mantras. But at that time that they had weapons, all we had were the tongues in our mouths.”

In 1979, he founded The Root, a black lifestyle magazine. Over a decade later, in 1990, he helped launch Choice FM (now Capital Xtra), the first licensed station solely for music of black origin, and a platform he used to actively campaign against knife and gun crime.

In 1979, he founded The Root, a black lifestyle magazine. Over a decade later, in 1990, he helped launch Choice FM (now Capital Xtra), the first licensed station solely for music of black origin, and a platform he used to actively campaign against knife and gun crime.

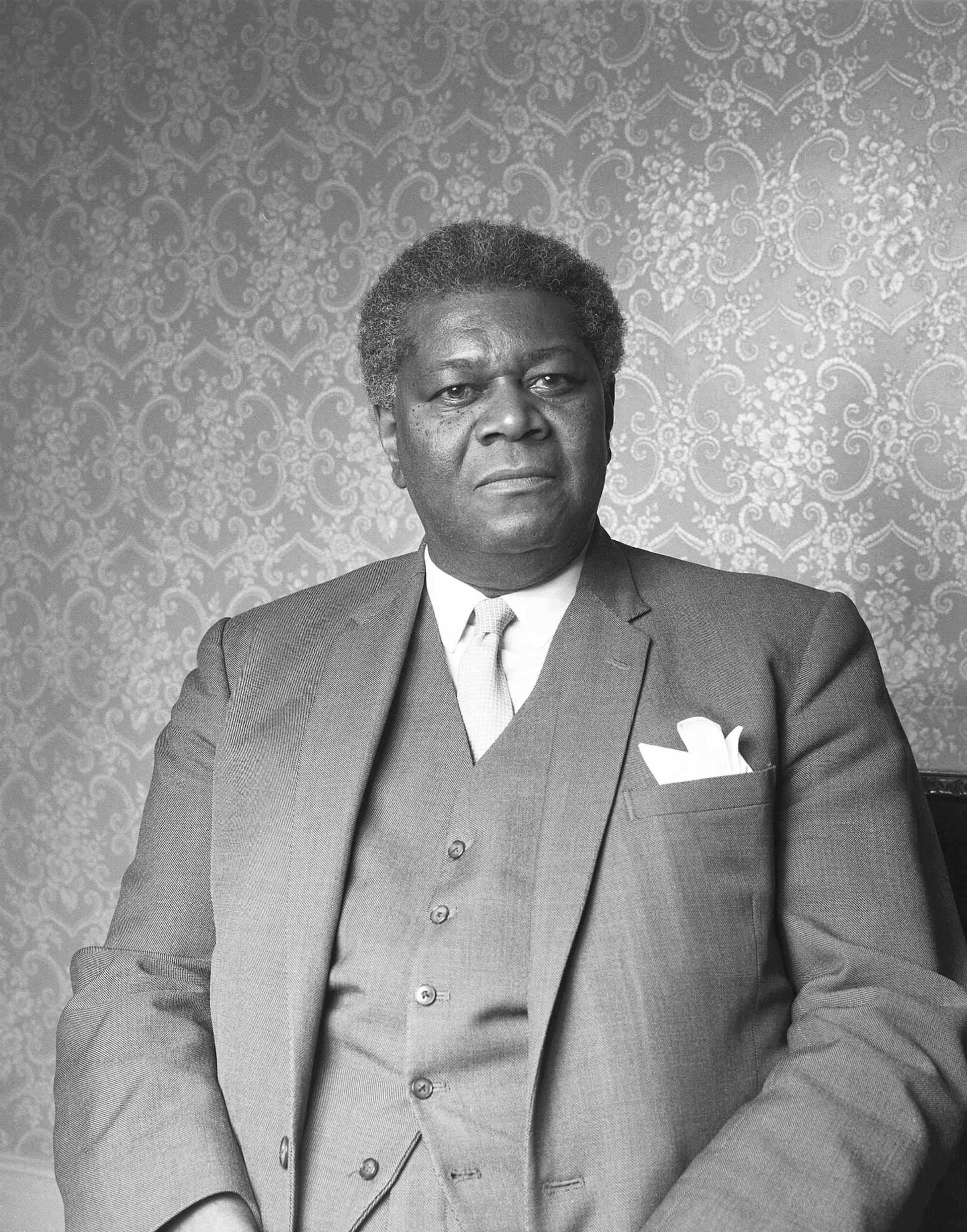

When it came to his photographic career, Kenlock’s work was a response to a pattern of weak or non-existent portrayals of black people within the press and media. He countered with this with authentic representations of political figures, activists and community leaders.

“Black people never had any personality, any strength, always looking down,” he remembers, with mild incredulity. “That’s not what I wanted my subjects to look like.” Instead, he says he used his photos to capture a humanity within the marginalised peoples, making it near impossible to ignore – let alone reject or deny.

Fast forward 40 years, and his work still succeeds in its initial objectives. Celebrated in a new exhibition at Brixton’s Black Cultural Archives (his first solo show in over 10 years), over 70 of Kenlock’s photographic images will be featured in celebration of the 70-year anniversary since the Empire Windrush arrival into Great Britain.

Fast forward 40 years, and his work still succeeds in its initial objectives. Celebrated in a new exhibition at Brixton’s Black Cultural Archives (his first solo show in over 10 years), over 70 of Kenlock’s photographic images will be featured in celebration of the 70-year anniversary since the Empire Windrush arrival into Great Britain.

In the wake of revelations regarding the UK government’s betrayals of the Windrush generation, Kenlock’s lens provides a unique window into the experience of Britain’s first-generation immigrants. Commenting on the scandal, Kenlock’s response is to-the-point: “Sorry is an easy word to say – ‘sorry’ and ‘we’re going to do something about it.’”

To him – and a large majority of the country – it seems baffling to remain silent on the subject of historical oppression, especially when the results of it are still so apparent in our society. For the sake of unity, as well as prospects in jobs, education and housing, an acceptance of guilt is of urgent necessity. (“That’s all we want… and it’s important for the rest of the nation to hear it from the government as well.”)

To illustrate his point, he states an age-old, succinct – yet heartbreaking – example of the ever-pervasive consequences of slavery: “Because my name is Neil Kenlock, but that’s not actually my name. My name’s African. I don’t know my name, but it’s not Neil Kenlock.”

The photographer’s work also documents the initial ripples of black leadership in this country, and explores how they paved the way for the incredible talents of today. (He captures the broadcaster Darcus Howes and the politically trailblazing Lord Pitts, for example, who preceded the likes of David Lammy and Edward Enninful). By highlighting the past generations of movers and shakers, he provides a much-needed context to the existence of immigrant generations here, both present and future – an existence that he views as both promising and inherently political.

The photographer’s work also documents the initial ripples of black leadership in this country, and explores how they paved the way for the incredible talents of today. (He captures the broadcaster Darcus Howes and the politically trailblazing Lord Pitts, for example, who preceded the likes of David Lammy and Edward Enninful). By highlighting the past generations of movers and shakers, he provides a much-needed context to the existence of immigrant generations here, both present and future – an existence that he views as both promising and inherently political.

Referencing the Reparations March that took place in Brixton in June this year, Kenlock says that he hopes these events divert the youth from negative influences and inspire them to “use their lens to tell the story” in the same way he did and continues to do. And, of the current political climate, his observation is brief: “I can see that the temperature is rising.”

His final message is that as long as we make ourselves valuable to the movements we truly believe in, the opportunities to communicate will follow. With a sense of satisfaction and slight wonderment, he concludes by considering the scale of his achievements. “I mean, 30 years ago I couldn’t tell this story. But I’m doing it now.”

Expectations: The Untold Story of Black British Community Leaders in the 1960s and 1970s is showing at London’s Black Cultural Archives from 7 August – 28 September, 2018.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.