Curiosity not propaganda: Ozier Muhammad’s incredible civil rights photography

- Text by Andrea Kurland (interview)

- Photography by Ozeri Muhammad (archive) and Andrew White (portrait)

This article appears in Huck’s Fiftieth Issue Special.

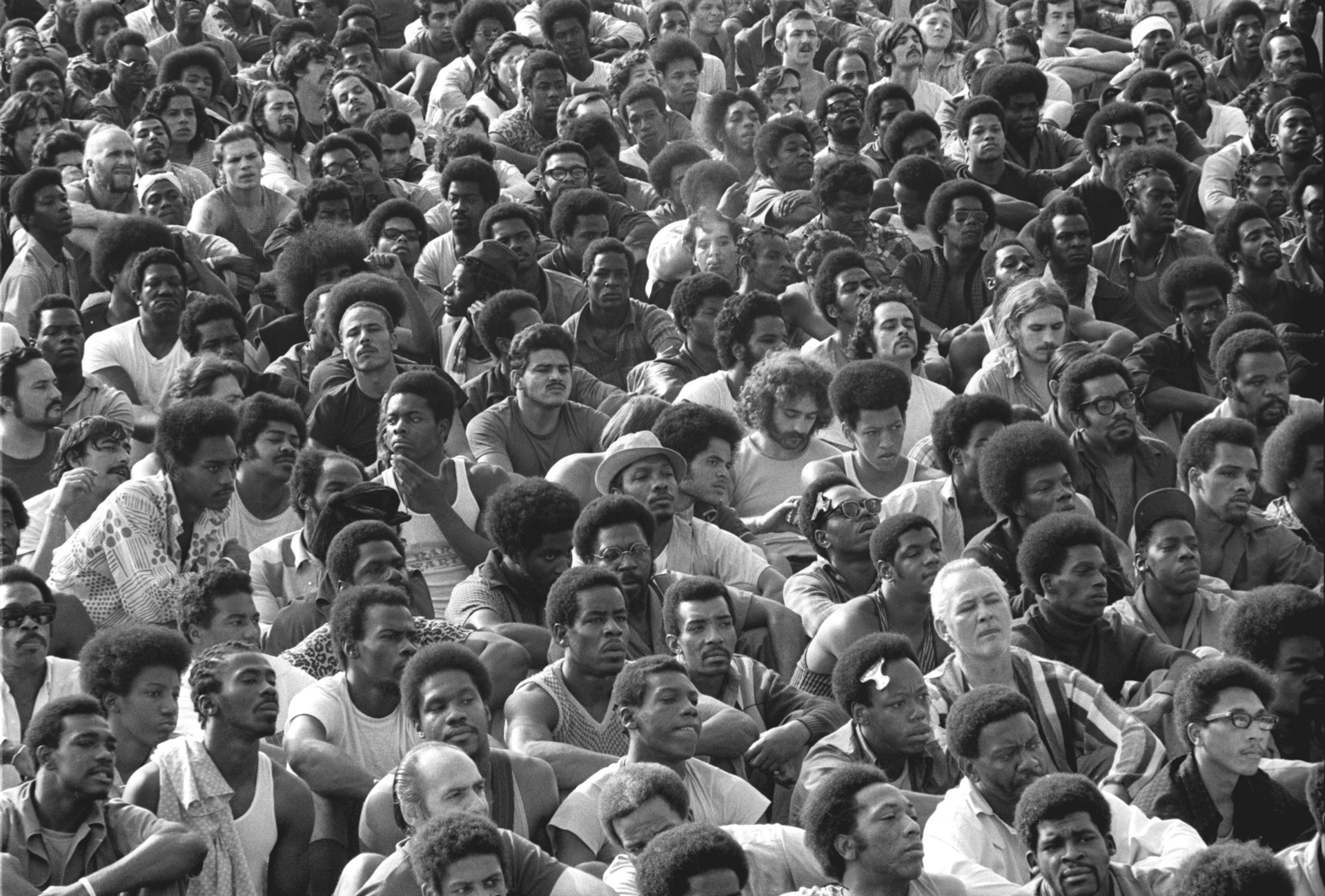

Ozier Muhammad grew up in ’60s Chicago surrounded by urgent voices. The grandson of Elijah Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam, Ozier witnessed the civil rights movement bloom throughout his youth, both firsthand and through the African American press. He took up a camera as a teen to join the photographers he admired who were ostensibly quarantined off from white-owned corporate news. And over the course of his career, starting out in the black press, he’s helped those boundaries break: at Newsday, in 1985, he was awarded a joint Pulitzer Prize for his work on African famine; and in 1992 he joined The New York Times where he stayed for the next twenty-two years.

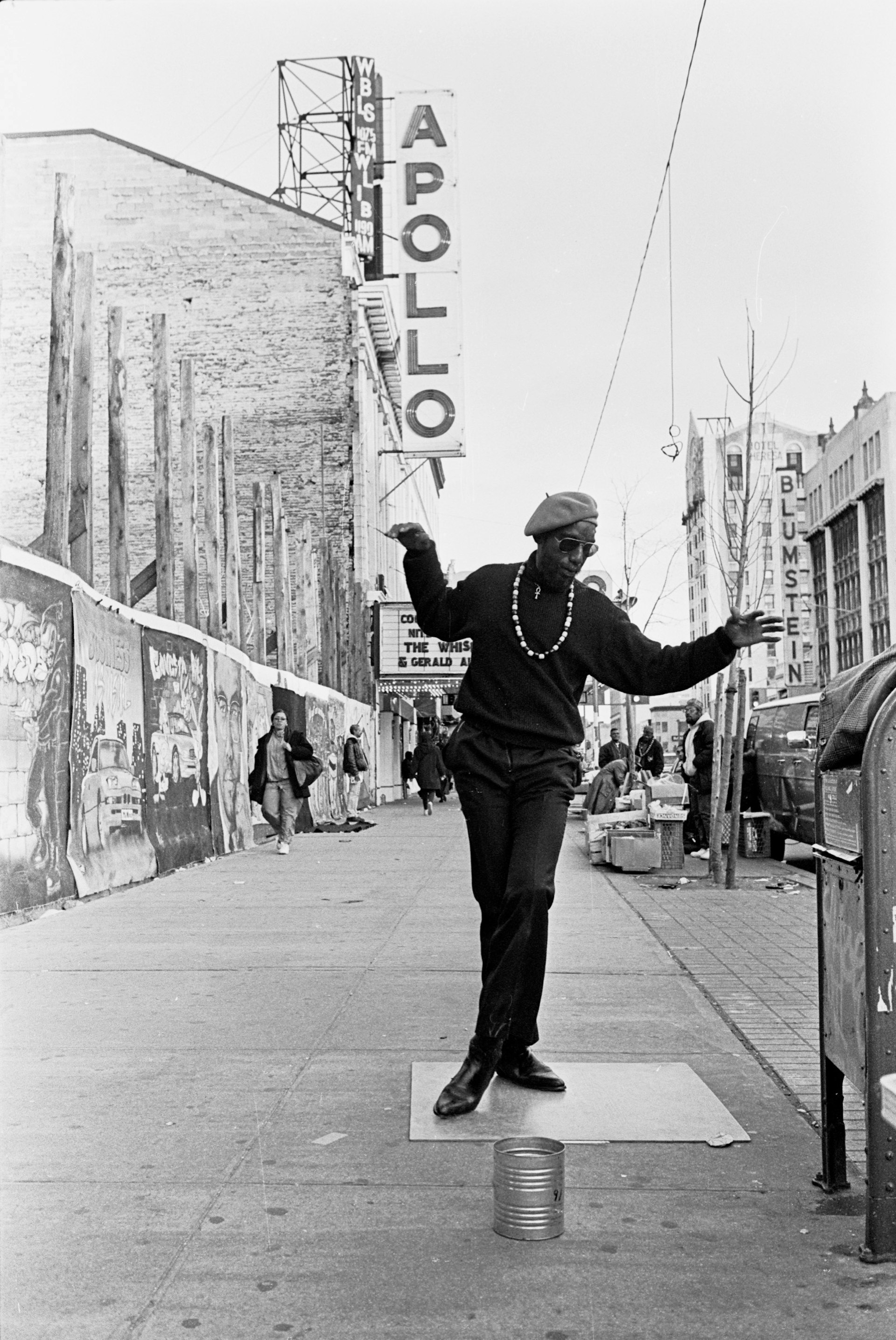

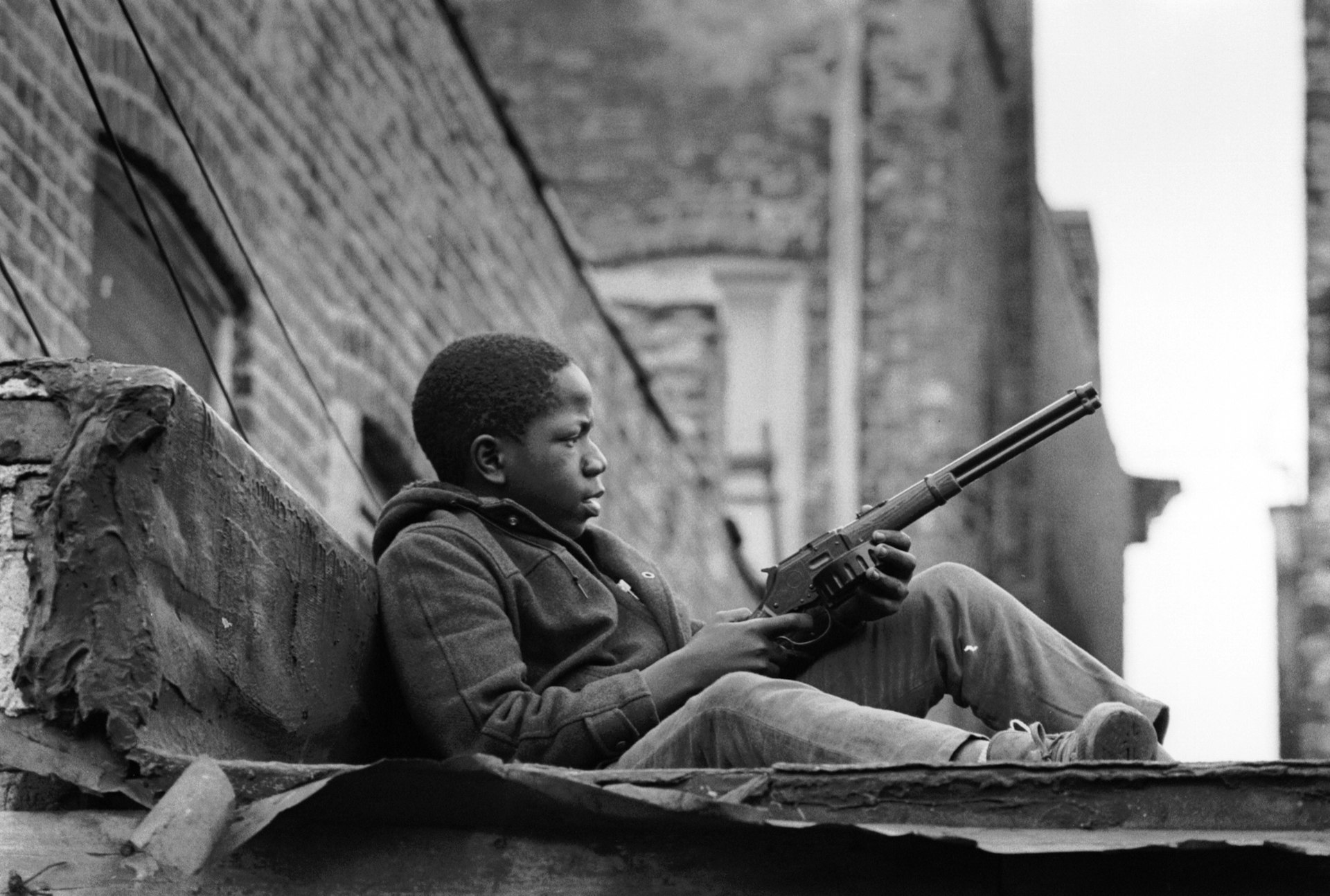

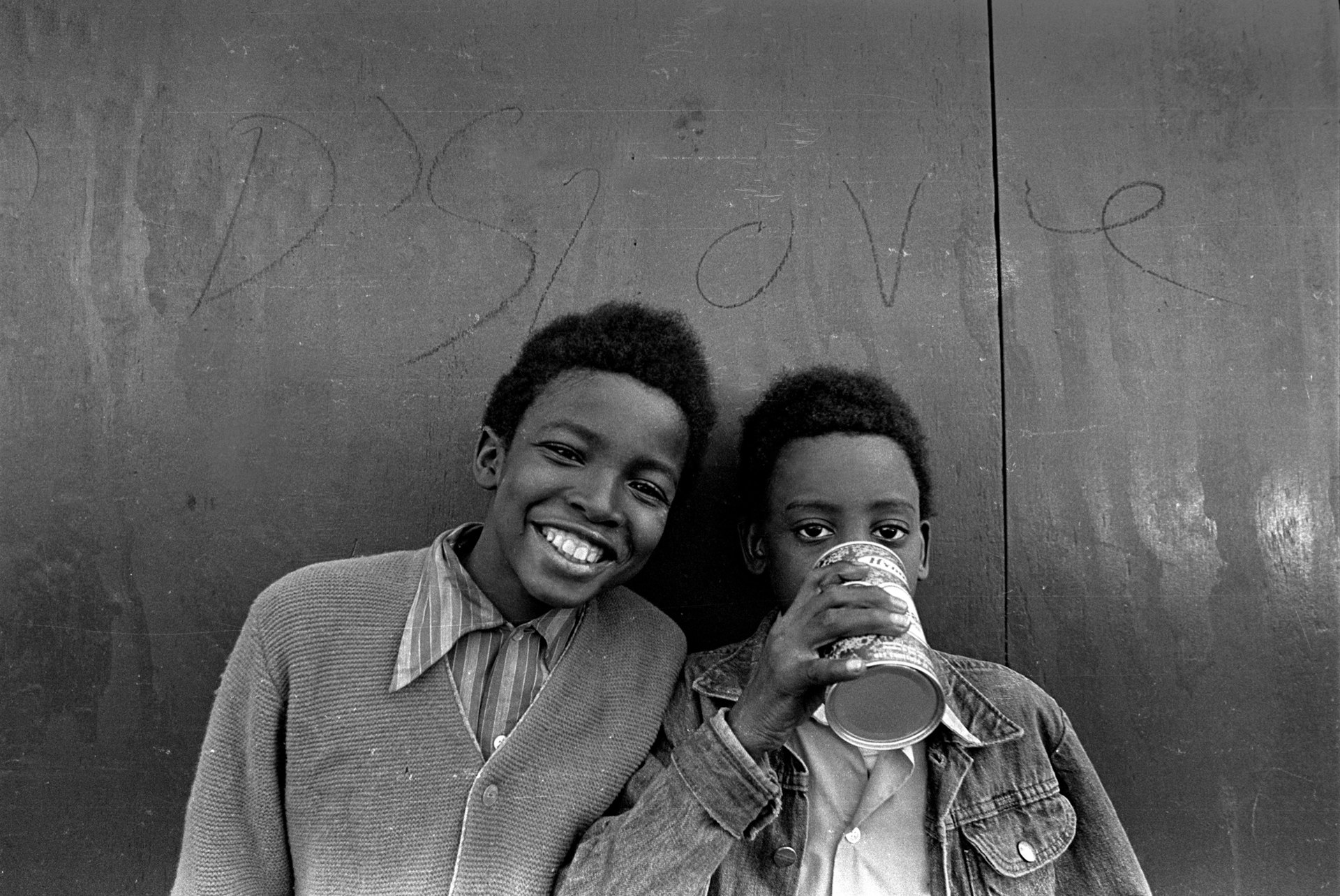

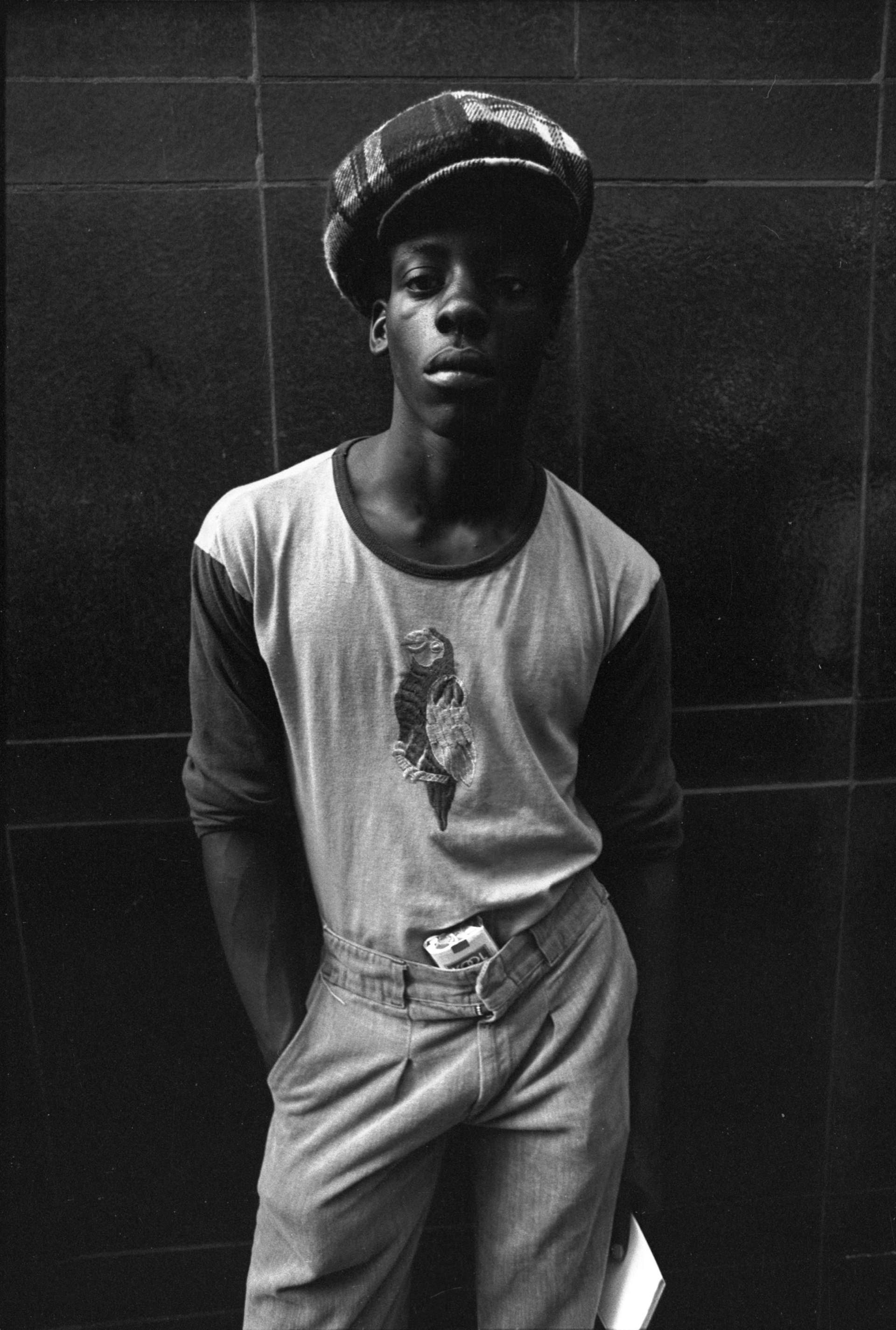

The images Ozier captured made front-page news – from South Africa’s first free elections in 1994, to Obama’s 2008 campaign. But it’s the quiet moments he caught at home, wandering through the streets of Harlem, that capture most intimately what he’s been striving for all along: a voice for his own community

“From a young age, I was impressed with images of the civil rights movement in the black press. My parents bought the Pittsburgh Courier, The Chicago Defender, Jet and Ebony. Chicago was a very active area for a large black community that was instrumental in the civil rights movement. Malcolm X was very influential, obviously. And by the time Muhammad Ali became involved in the Nation of Islam, the popularity of the community had soared. These were people I saw up close as a teenager, but I had a keen interest in how the greater world looked back at us – how we were reflected in the journals. And for a teen, the easiest access was photography.

“I got my first camera at fifteen and from that point on everything just seemed to thrust me in the direction of becoming a photojournalist. Some of the great photojournalists in the ’60s covering civil rights were in my community in Chicago: Bobby Sengstacke, Gordon Parks, Eve Arnold. I liken the impact of their images to when someone says Mozart’s ‘Fifth Symphony’ takes them to another world of insight. Like the poetry of Rita Dove, or a solo by Miles Davis, it touches your humanity.

“It was difficult to get work as a black journalist. What changed that in the mid-’60s was the LA riots, and the riots that followed Dr King’s assassination in 1968. The vanguard who first went into the newsroom were not trained journalists. They were already in the buildings working in the mailroom, or maintenance, but when white reporters encountered hostility covering the riots, black reporters got their break.

“The press never covered the black community in the way it does today. The reason there was a change is just simple economics. By the ’80s, there was money to be made by ceasing to ignore this community. Why not have them increase your circulation? Prior to that, if you wanted to read about African Americans who were striving to better themselves, or you wanted to know about stories like the Tuskegee experiment, where a US military unit was injecting African American men with syphilis, you had to rely on the black press. In the ’60s there was a clamouring for the Chicago Tribune to pay more attention and the response of the owners, the Fitzpatrick family, was: ‘We’re not interested in covering them because they are illiterate.’ That racial attitude about the wherewithal of the black community to absorb world affairs was also a problem at The New York Times and the LA Times in the ’50s and ’60s. Why would they read our journal when they don’t have the capacity to understand world events?

“I felt compelled to be a sort of foot soldier; to walk around my community and try to convey, in the most compelling way, exactly what I saw.”

“By 1975, in order to mature as a photojournalist I had to leave the black press. It became one-dimensional, focused on success stories, and I thought that too many of us were still struggling. I didn’t want to visit homes in Hyde Park Chicago, photographing surgeons or pop stars with six Cadillacs in their driveway. There was too much focus on materialism rather than, ‘How do we improve our condition?’ Ironically, I felt that if I worked for the mainstream media I could do that.

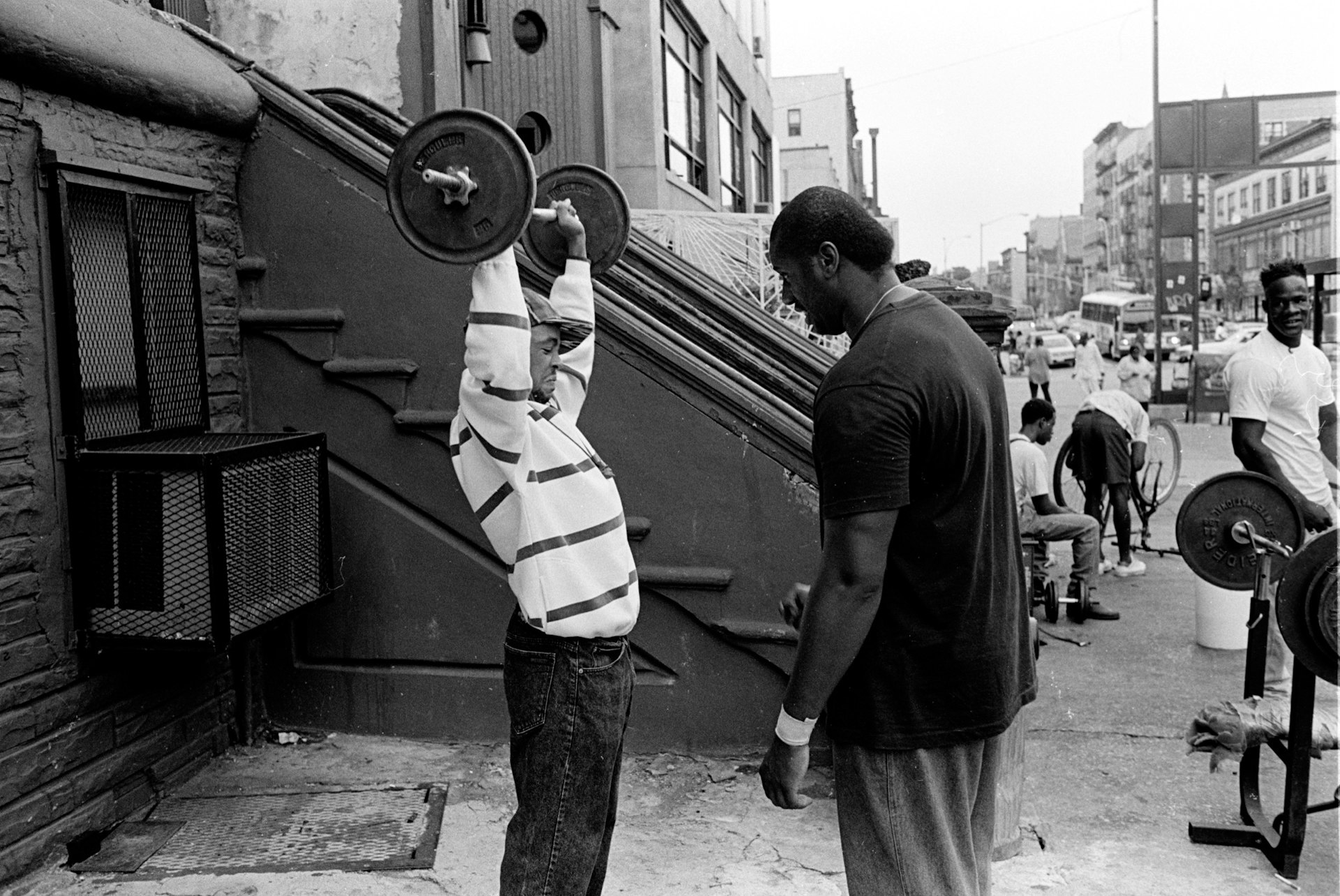

“In 1992, I joined The New York Times. As an African American, I could go to that editorial meeting and have a voice. When they solicited me for ideas I could say, ‘Hey, why don’t we do something on black youth unemployment?’ Kids just doing whatever they could to survive. There was this one guy who started a gym outside, just off 125th Street, to get young men healthy. These were the stories I was interested in.

“Unfortunately, the mainstream press is not serving our community well today. In the early ’90s, there were more African Americans on staff, but when the Internet came around the newsrooms slowly faded to white. Resources were often blamed. I know several of my colleagues at The New York Times asked why this persists. And to my surprise one of the publisher’s answers was, ‘We’re having a hard time finding talented African Americans.’ This sounded like something one would hear in the ’60s. It blew my mind that that was his answer.

“I’ve always tried to look at the African American community in the most honest way I could. Every community has its beautiful aspects and its problematic ones. The ugly and the beautiful. I tried to preserve in imagery some of the things that moved me, like witnessing the struggle of a people, to show viewers that this is simply an attempt to convey a fluid situation. But I also loved documenting the cultural impact – photographing jazz musicians, or walking up and down 125th Street, the main thoroughfare through Harlem, documenting people living their everyday lives. I wasn’t trying to be propagandistic or say, ‘Look how wonderful my people are.’ Just the act of paying attention to the African American community, just taking an interest was important to me.

“They say journalists are the first chroniclers of history – the first historians. So I felt compelled to be a sort of foot soldier; to walk around my community and try to convey, in the most compelling way, exactly what I saw.”

This story has been condensed from an interview. It originally appeared in Huck’s Fiftieth Issue Special, a collection of fifty personal stories from fifty inspiring lives.

Grab a copy now to read all fifty stories in full. Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.