The Parisian street gangs who fought fascists in style

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Philippe Chancel, courtesy of Melanie Rio Fluency, France

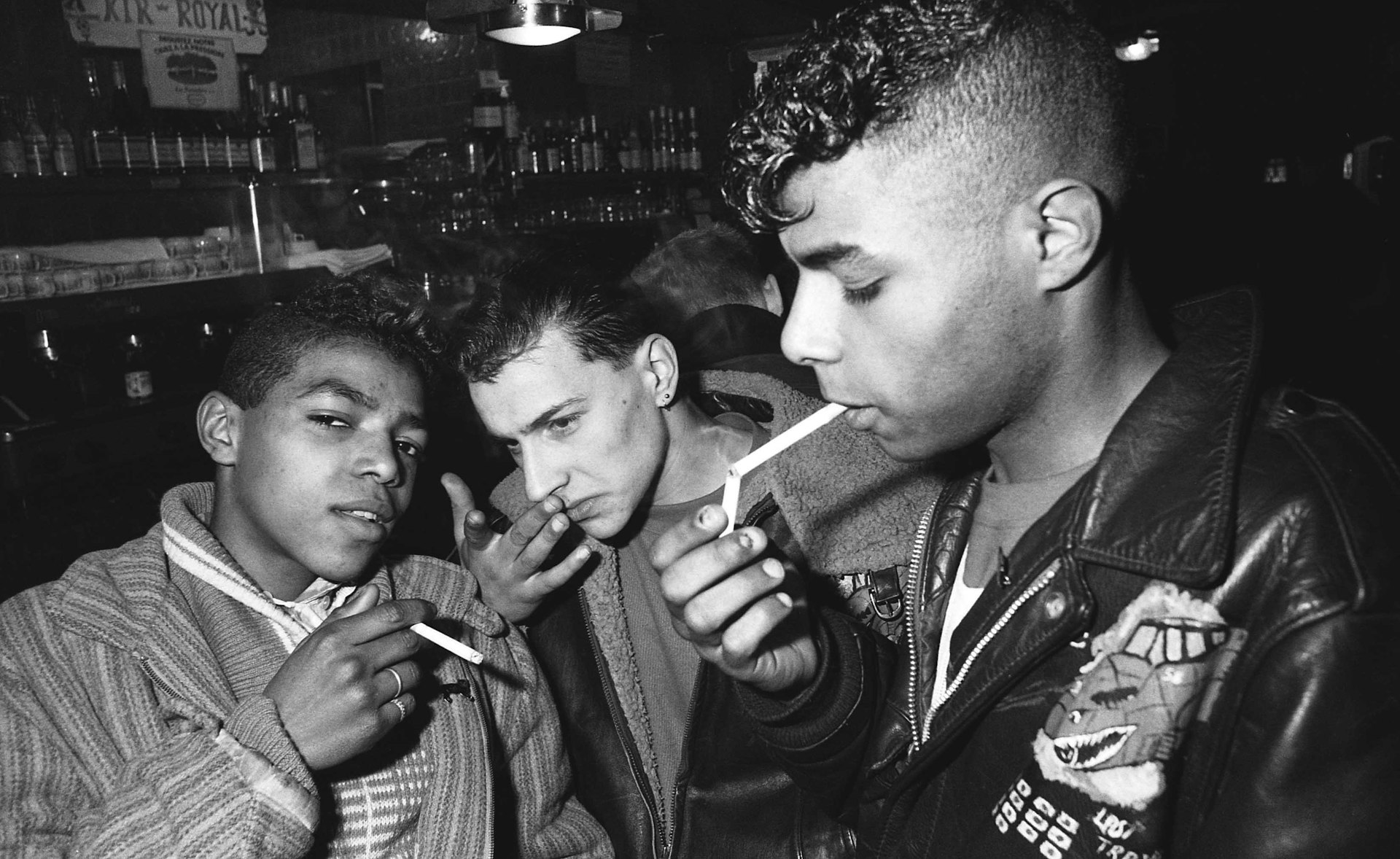

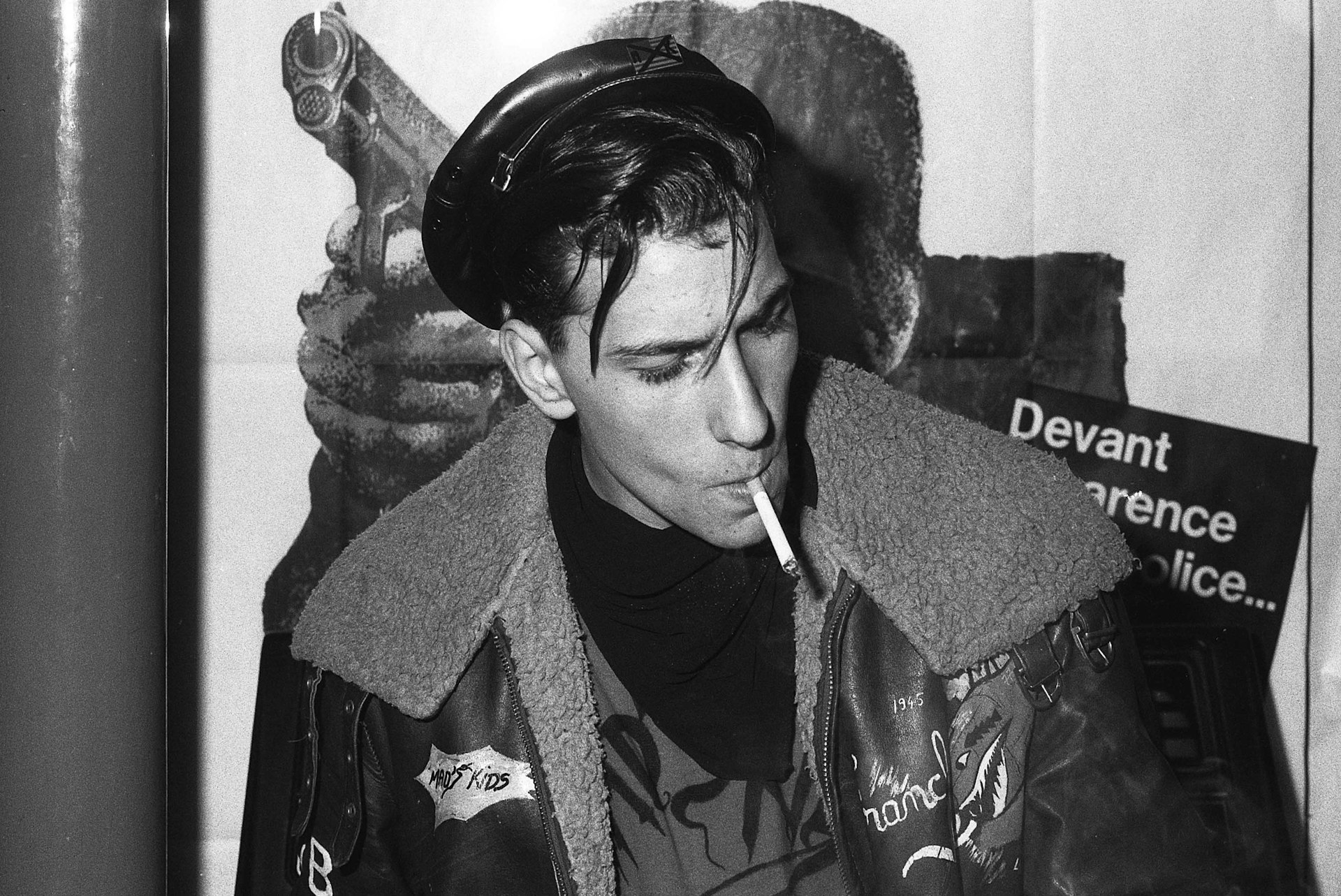

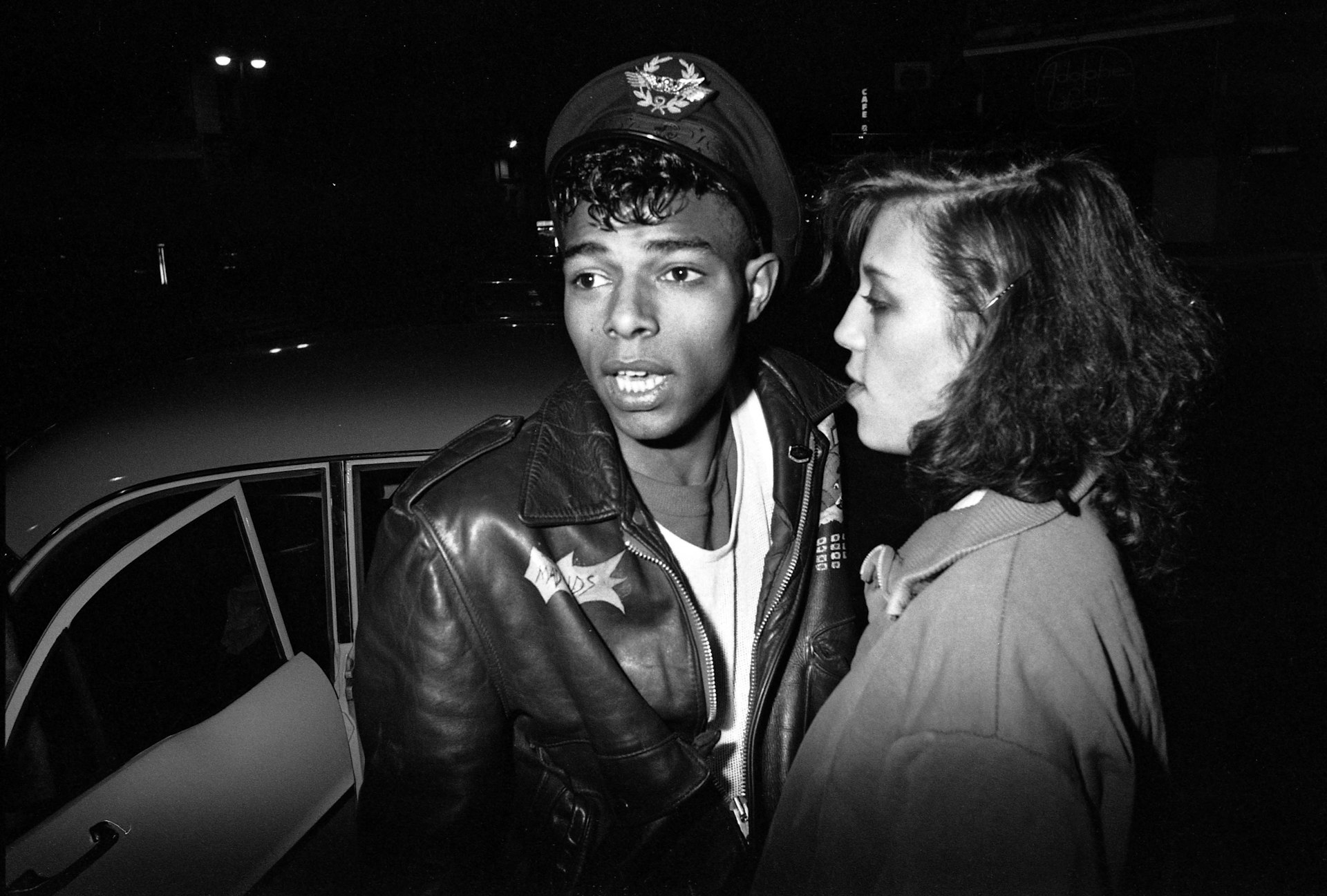

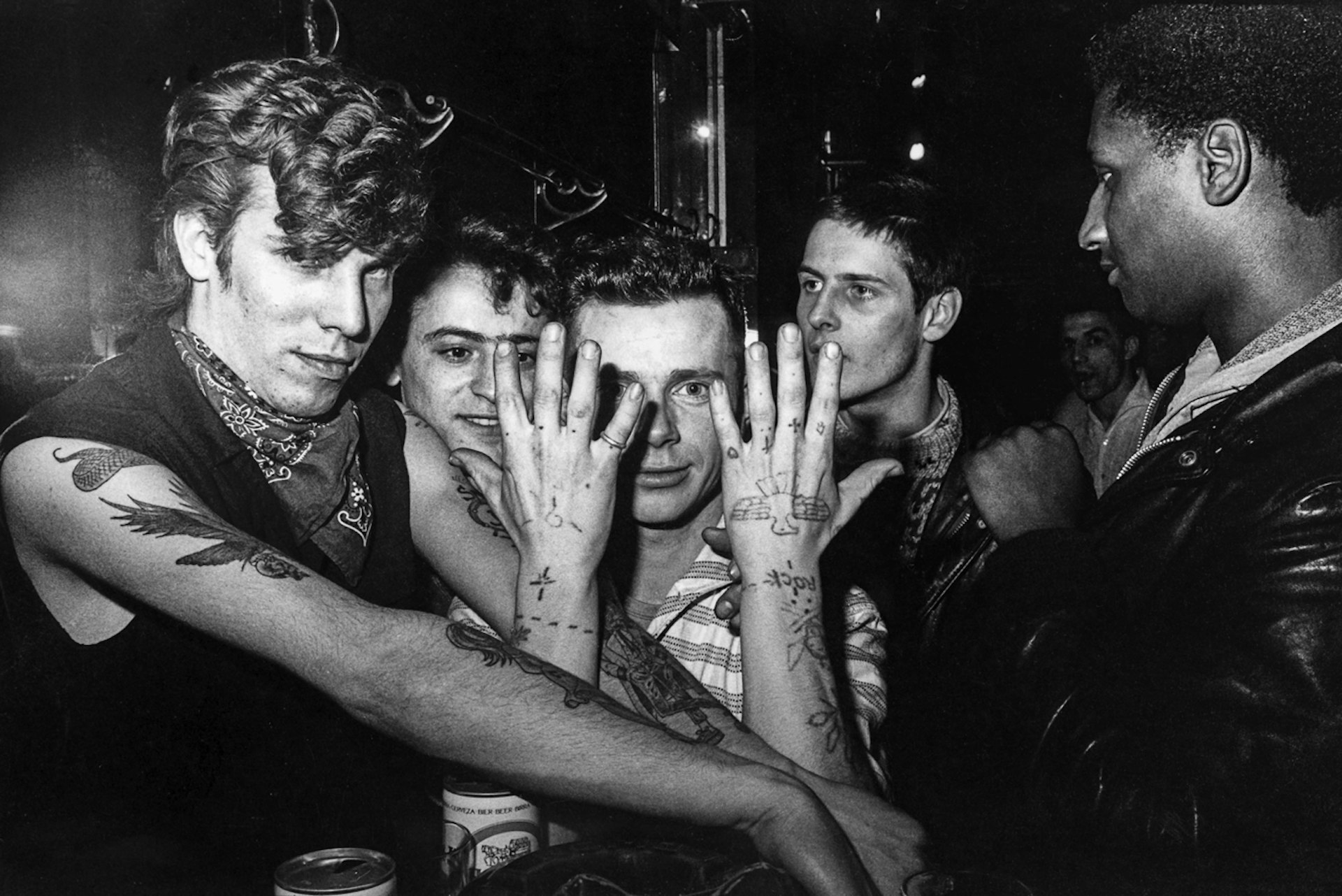

In the early 1980s, photographer Philippe Chancel immersed himself in the world of two rockabilly gangs: the Vikings and the Panthers.

Inspired by the style of 1950s Americana and comprised of various ethnic backgrounds, they were branded ‘skinhead hunters’ for their violent clashes with rightwing rivals across northern Paris.

France was undergoing a turbulent time, with unemployment spiralling and aggression towards immigrants on the rise.

Chancel, meanwhile, was still looking for his place in life. His brash confidence earned him acceptance among the tribes of teen gang members he encountered on the capital’s streets – an experience that shaped an impressive career in photojournalism, documenting war in Afghanistan and life in North Korea.

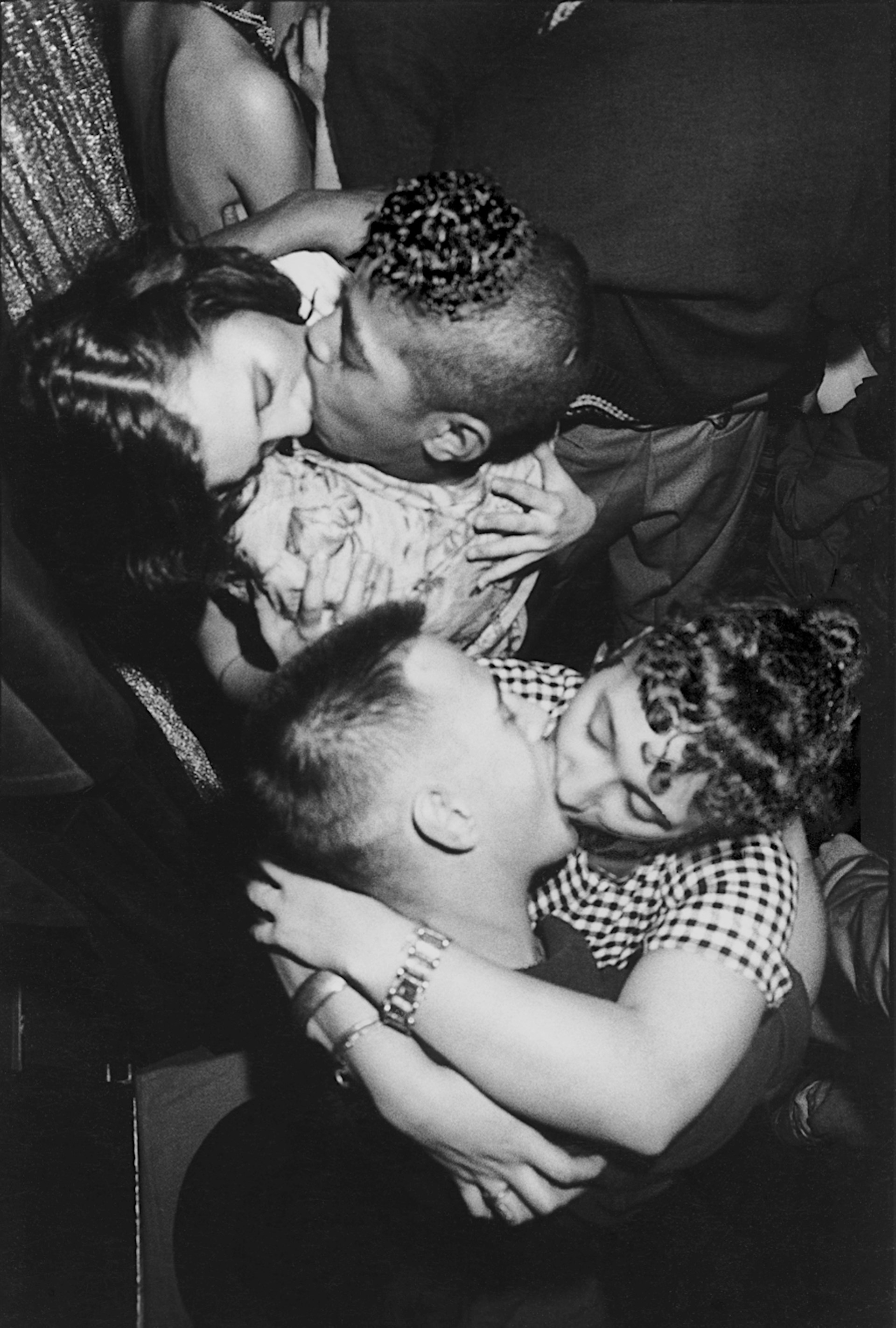

The images he captured of the Vikings and the Panthers – striking black-and-white shots imbued with intimacy – were published in a counterculture magazine called Actuel but were forgotten about until being rediscovered recently.

Now that the work is being shown in London as part of the Barbican’s Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins exhibition – a celebration of the outsider as an agent of change, which ends on Sunday 27 May – Chancel took the time to reflect on the project’s significance.

Why have these images remained unseen for so long?

Honestly, it’s a question that’s only coming up now. These images sat in my archives for a long time, after limited initial publication in the French underground press.

A few years ago, when the artistic director of a rock label contacted me to see them – he’d seen a photo I’d given to one of the Vikings shared on social media – I took that as a sign.

My gallery Mélanie Rio Fluency presented them at Paris Photo two years ago. Then Alona Pardo from the Barbican spotted them and, with her exhibition in the Barbican in mind, decided to display them.

How did you get started in photography?

I started very young and, with age, this became a great passion – an act of love, in a way. If I take stock of the distance travelled since, even measured in only clicks and whirrs, the exposure time is very long… and yet, even now, it’s still the next photoshoot that matters to me, and nothing else.

I owe everything to photography, it lets me travel the world, it feeds my curiosity, enriches me with experiences, discoveries, encounters, and makes me take risks too – something that really drives life.

What did it feel like to immerse yourself in this rebel subculture and how did you gain their participation in the project?

Working with the Vikings and the Panthers – it wasn’t easy to be accepted by both groups – was the grand adventure of my twenties. I was seduced by the margins of humanity and society as a way to find myself. I had also just spent a month in a centre for mentally ill youths in order to confront the harsh reality of madness and try to give it some kind of joyousness through my photos.

The film version of West Side Story, starring Nathalie Wood, was my reference at the time for how I might build an enduring story with them. I was that guy who wants to be in the gang but doesn’t want to choose sides, and then takes photos too! How was I going to be welcomed among them in these conditions? By acting like a tightrope walker, is the answer!

I spent more than six months with them and experienced as many moments of tension and violence as I did charm and exaltation. It was this raw energy that I sought to capture with my camera, loaded with Kodak Tri-X and given a boost by my flash. Though sometimes I acted with cunning and surprise, I always spoke with truth and sincerity… though with a large dose of naivety, I must admit, looking back… and maybe even recklessness at times.

Of course, you have to share an empathy with your subject, otherwise nothing happens; nothing penetrates the image. It’s your status as photographer that has to get you your foot in. Find your space at just the right distance. For a photographer, signs often matter far more than long discussions.

I was regularly accompanied by a journalist, Pierre Hurel, who helped me a lot in dealing with delicate situations. He later became a renowned director of television documentaries, specialising in portraits of politicians, like his recent one on Emmanuel Macron.

How do you think young people’s tendency to identify in tribes and styles has evolved over the decades since these pictures were taken?

The ’50s revival at the beginning of the ’80s led to strong cultural references among the Vikings and the Panthers, in the look, the attitudes, the musical references. I was totally captivated by that; but they weren’t seen in the same way as the modern young people of the New Wave movement.

In today’s context, 35 years later, what strikes me is their clear-as-day authenticity. The fashion industry didn’t exist yet and social markers weren’t yet dictated by brands! Their dress codes were copied from no one and fully reflected their personalities. In other words, it wasn’t yet the time of just remixing everything.

What kind of parallels do you see between the current political climate in France and the one in the 1980s?

The political climate in France has completely changed in 35 years, the “black, blanc, beur” France (“black, white, Arab”), that dream of integration and equality of race and class held up by the newly empowered Left has transformed into talk of globalisation and analysis on the gap between the world of rich and poor, widening in front of our eyes.

France has doomed itself to succeed, even if that means abandoning its universal values, as has happened everywhere else. Resistance has become radicalised and terrorism has blurred the myriad nuances of the Republic and now installed order in every facet of life is once again the only hope of a future without security measures.

And to complete the picture, the waves of migrants are seeing a revival of racial and anti-Semitic tensions. In this light, my rebels would seem like choirboys of the extreme Left!

What did you learn from this project that you could apply to work later on in your career?

I learned a lot with the rebels. Without really realising it, I was going beyond photojournalistic reporting related to the news and moving into the documentary format that is built over time and that aligns itself more to the story and to the subject, as a political base arising from the social milieu, than it does to highly-strung emotions overflowing with pathos that obscures any original meaning.

It’s about finding the right distance. All the projects I developed afterward sought to capture this same guiding principle, that singular fact that carries it beyond simple story-telling in an effort to show the present of what will go on to make history.

What do you think this collection of images says about what it’s like to be young? Or to be an outsider?

All revolutions in all spheres are carried by the strength of youth! This is where the catharsis happens!

What image do you feel most connected to in this project and what is the story behind it?

The kissing photo. This couple, with such an unlikely look, embracing each other; and the heart outlined by folded arms. I took this photo during one of the parties organised by Albert on Friday evenings on the Grands Boulevards before the police got involved and prohibited the place. That night, Brian Setzer, frontman with the Straycats, was there. It was a competition actually: a competition for the longest kiss. P’tit Jean and his girlfriend were the winners.

Do you feel like there’s anything in your personal life that drives your work?

My personal life and my work are inextricably linked; perhaps for the worse! I like quoting this sentence from a French artist I love, Robert Filliou, a sentence the mayor quoted during my wedding on 08/08/08: “L’art est ce qui rend la vie plus intéressante que l’art.” (“Art is what makes life more interesting than art.”) That says it all.

What’s the best advice you could give to someone?

I don’t like to hand out overly learned advice. I like to provoke but, at the same time, I need to say things in order to do them and I like to set the bar ever higher. This implies not being afraid to throw everything back into question in order to never stop advancing, even at the risk of being totally wrong and never recovering.

What’s the key to developing your own style and finding the right subject matter?

In the sphere of documentary photography, though at the start we may be vain enough to think it’s easy to go and conquer the world, that illusion is quickly smashed. It’s the world that shows itself to you, or that doesn’t show itself: your humble job is to see which is the case.

Another Kind of Life ends at the Barbican on 27 May.

This interview has been translated from French by Vanessa Peral and Christopher Stevens.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.