The small coastal haven that became an outsiders’ paradise

- Text by Benjamin Cook

- Photography by Joel Meyerowitz

Provincetown has been offering shelter for centuries. A small town perched on the end of a sandbar jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean, it was here that the Mayflower Pilgrims first came ashore in the winter of 1620.

The 20th century brought poets and painters, drawn to the natural beauty and unique light. And when the great and the good of Greenwich Village descended every summer like a royal court procession, they transformed a sleepy fishing town into a hotbed of creativity and self-expression.

By the time photographer Joel Meyerowitz arrived during the summer of 1976, the likes of Andy Warhol and John Waters were already regular fixtures. “Provincetown was a real party town,” he remembers. “There was always an electricity in the air.”

Caroline and Margaret, 1983

Having spent a decade making his name as a street photographer, Joel, like so many artists before him, was drawn to Provincetown by the promise of “a light that seemed to illuminate everything from within”. Feeling constrained by the limitations of the 35mm format he’d favoured previously, he picked up a six-foot-tall, wooden, 8×10 camera in Salt Lake City and made his away across the country, heading for Cape Cod at the suggestion of a friend. Once there, he set about capturing something that was, back then, entirely new to him: portraits.

“There was this incredible openness that drew me into photographing people there,” he recalls, a warm smile spreading across his face. “I took in everybody – but anytime I felt a kind of spiritual connection, I wanted to take their picture. Sometimes I would see somebody and feel a sort of vibration between their identity and my own.”

“My job was to try and keep the thread of energy between us alive. To get them to reveal their mystery, because we all have a mystery about us. I was only going to take one shot, so I waited for that moment of revelation.”

Norman and his son John Buffalo, 1982

Joel would return to visit the coastal town every summer for 35 years, seeing it as the perfect place to bring his children due to its welcoming attitude. “One of the great strengths of that little town is its understanding and its tolerance. Anywhere that there is a kind of land’s end quality, people seek refuge and get away from it all. There’s nowhere beyond that but the ocean. I think it creates a sense of community that accepts everybody.”

That tolerance made the place a haven for anyone ostracised by mainstream society. Interracial couples, queer partners, trans men and women: they were all drawn there. Provincetown provided a space for people to be free – which, back then, was particularly invaluable to the LGBTQ community.

While the town of Joel’s photography is idyllic, it’s impossible to escape the looming spectre of the AIDS Crisis. Joel chose not to feature shots of anyone living with HIV in the collection, as he wasn’t looking to politicise the work – or make a statement about a particular issue. But he recalls powerfully how the town stood strong through those years, always offering shelter to those who needed it.

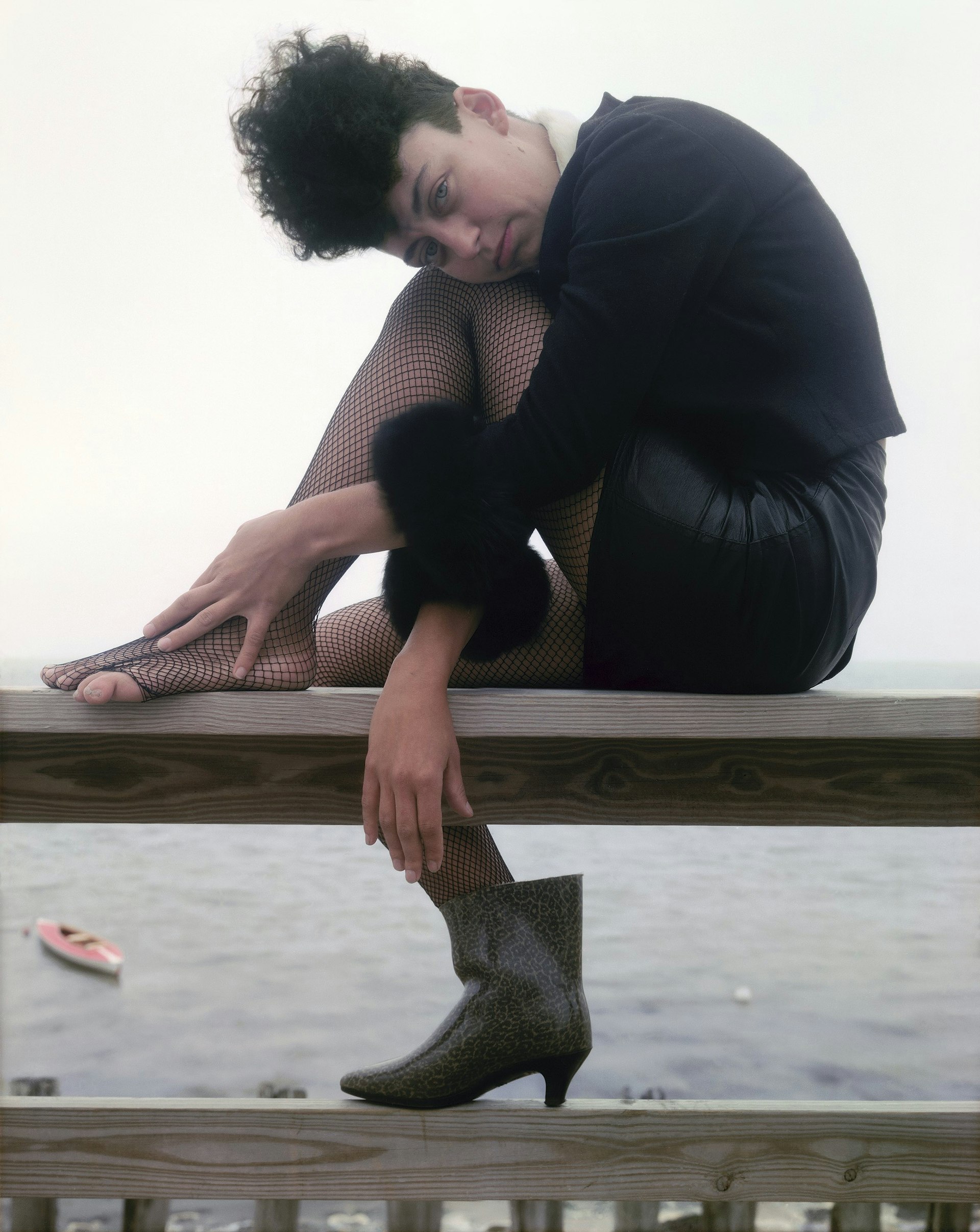

Renee, 1981

“I lost a lot of friends in Provincetown. There were people walking around like ghosts, being helped by their lovers and friends, but at the same time there was a revelry. People were saying, ‘I’m young, I’m beautiful, I’m strong. It’s not going to get me.’”

“There were people who were obviously not going to make it, but they wanted to see Provincetown one last time,” he continues. “It’s so beautiful there. The atmosphere there is so clear it’s like a crystal. A lot of people wanted one last look, they wanted to go there to say goodbye.”

For decades, these photographs remained undiscovered in Joel’s archives, slipping between the cracks of a long and storied career, until his archive manager brought them to the attention of Aperture. It led to them being published for the first time in a new book, itself titled Provincetown.

Stephen, Lynette and Jack, 1981

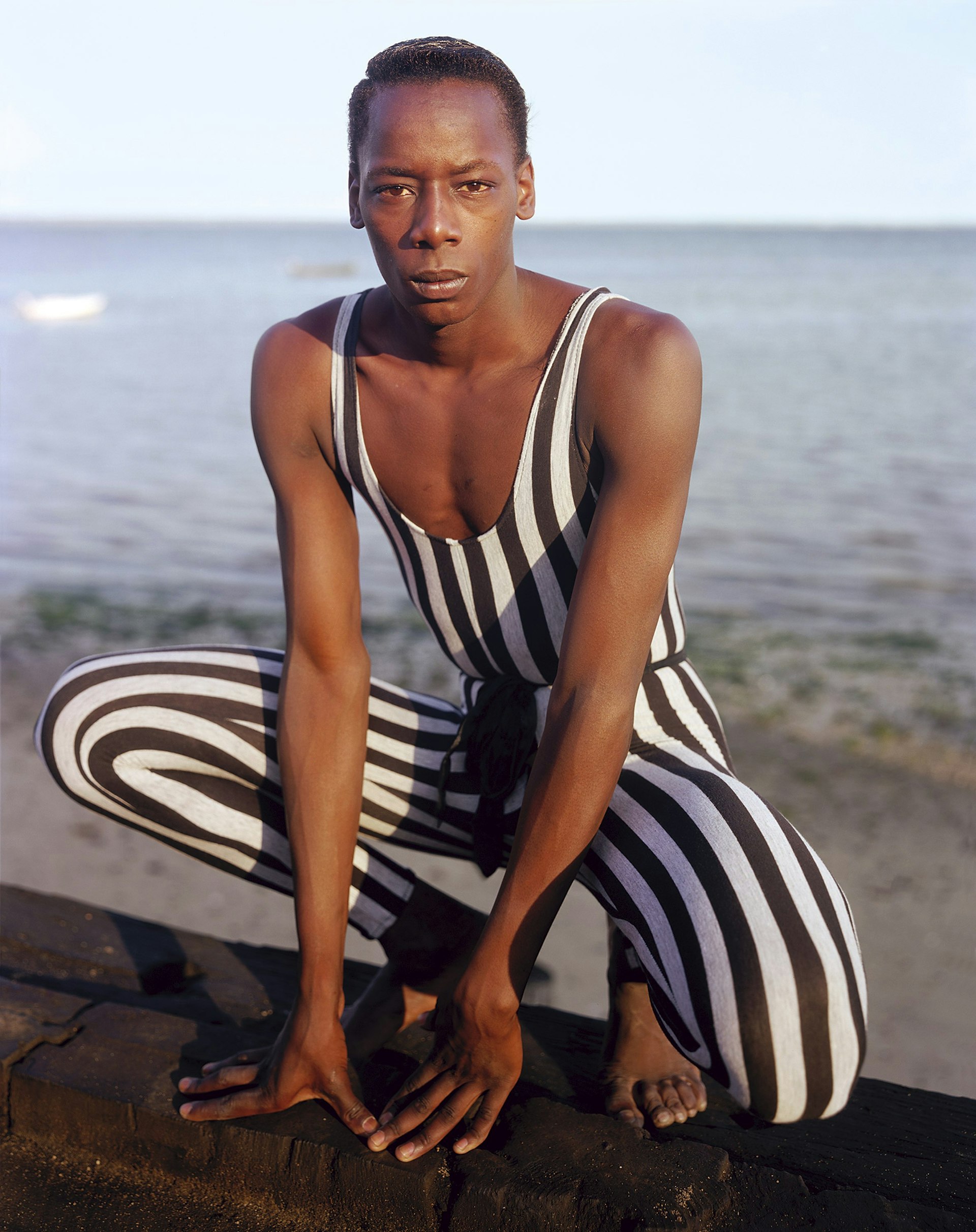

Making the book, he says, has allowed him to revisit the photos he took as a younger man. In that sense, he has been taken back to the shores of all those years ago. There’s the shot of Darrell, a dancer who worked at a nearby hotel, crouched in his striped leotard. Joel was drawn to his beauty, noticing him performing ballet by the ocean. Elsewhere, the American writer Norman Mailer clutches his young son, John Buffalo, close to his chest, in a display of intimacy that feels unique to the place in which it was captured. All of them – along with the lovers, the bohemians, the runaways – found themselves in front of Joel’s lens. All of them, in Provincetown, were free.

“People from all different walks of life came to that little town – you felt like you belonged, like you could be yourself. You open this book and you’re transported there. That’s the wonderful thing about photography, it’s like a time machine.”

Denise, 1985

Carol, 1980

Darrell, 1983

This article appears in Huck: The Utopia Issue. Get a copy in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Provincetown is published by Aperture.

Follow Benjamin Cook on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.