What it means to document the everyday reality of black America

- Text by Ruddy Roye

- Photography by Ruddy Roye

This article appears in Huck 57 – The Documentary Photo Special IV.

The act of staying alive is a protest. If you have to survive in a neighbourhood where there are drugs and crime, for me that is a protest.

When a mother says to her child that he can’t play out on the street after a certain hour because she’s expecting the boys to be coming out, that’s a protest.

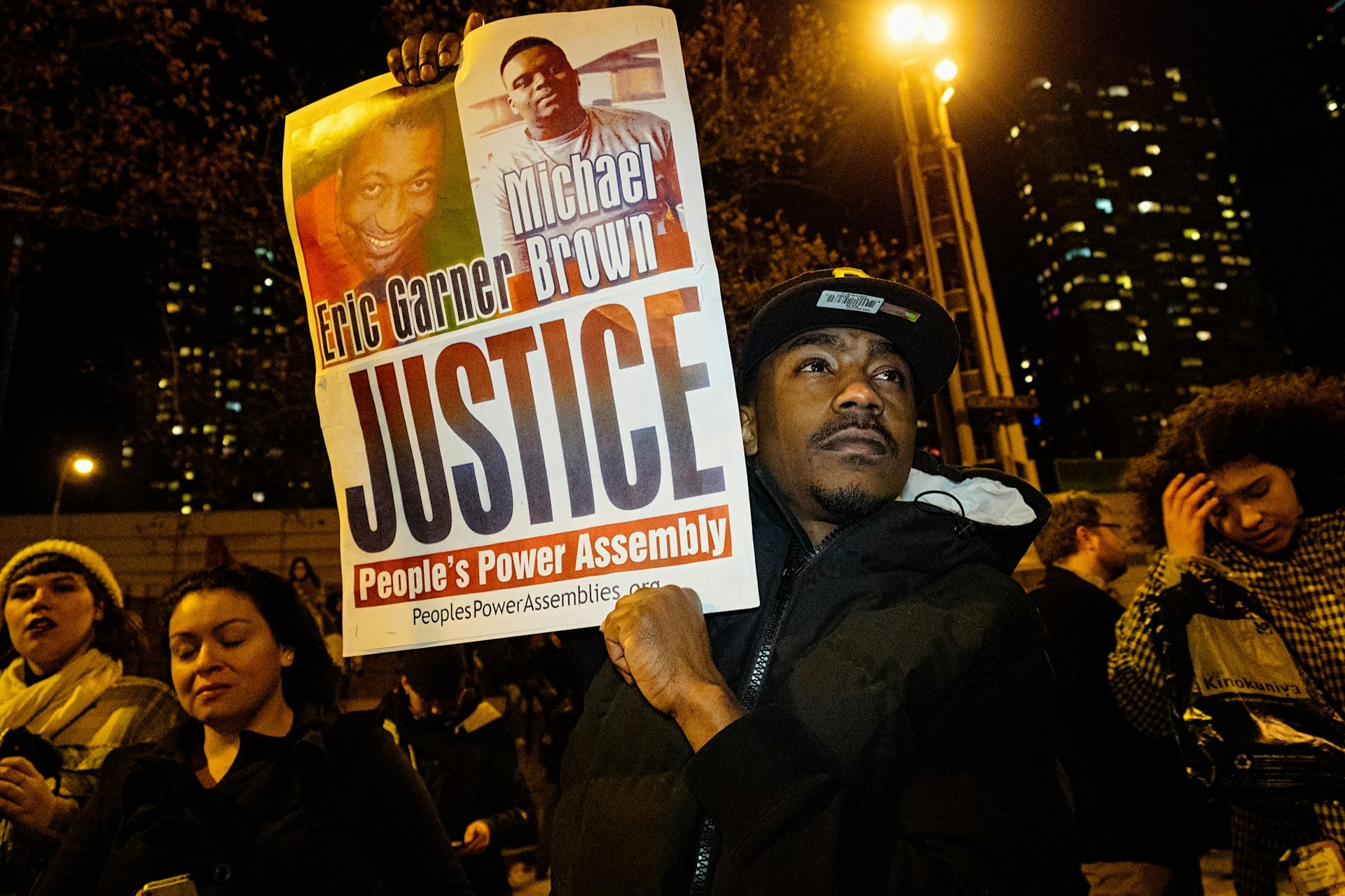

The huge marches in Ferguson or Manhattan are a visible form of protest, but I’m looking at it in a more abstract way. For me, activism is a way of life.

“Why was he shot so many times? asks 19-year-old Dante Newsome, reflecting on the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

We’re all activists. Activism does not necessarily mean that your sole purpose is to shine light on the things that you believe in. Activism is care.

I care about humanity. I don’t just care about black folk. I don’t believe in black neighbourhoods and white neighbourhoods. I believe we should all live together.

When Living is a Protest began from my need to be seen as a photographer: a black photographer.

Walking around my neighbourhood, Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn, I would feel like the people who were going through hard times were going through the same things that I was – both as a man and as a professional.

That mirror made me feel like I needed to document it just to help me understand the place I’m in.

The second step was a question: if this is what I’m seeing on a daily basis, what does it do to the black psyche?

“Someone has to stand up to these crooked cops and now is the time,” says Lawrence McNair while standing on Florissant Street in Ferguson, Missouri.

I realised that if all you see around you is depravity, poverty, sickness and disenfranchisement, then there’s nothing to stop you from allowing the place to fall into disrepair.

I have been taking photographs every day for the last 17 years, using my own neighbourhood as a palette – so my palette is dark.

There’s nothing particularly remarkable or unique about any of the people I’ve shot, but there’s something that resonated in me with every one.

A makeshift shrine commemorating where Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri.

Whenever I go beyond Bed-Stuy – to Ferguson or Dallas, Cleveland or Baton Rouge – that’s just my way of stretching my legs, extending the project to look at what exists elsewhere.

My images are not divisive – I hope. I’m trying to make pictures that inspire people to say, ‘You know what, we need to be more vocal, we need to be more vigilant.’

Silence is a crime. If the person who looks at my images has a problem with them, then he’s the oppressor.

I use photography to show that we are also humans: the only difference between me and you is the colour of my skin.

Michael Brown Sr. walks into the Friendly Temple Missionary Baptist Church, St. Louis, Missouri, to attend the funeral service of his son, Michael Brown Jr.

It’s my way of introducing my culture to the other. My story is your story.

Harriet Tubman [a pioneering abolitionist during the Civil War] did not make it to the North just because black folks helped her.

She was able to elicit courage, help and assistance from white folks. In my own way, I’m trying to introduce people of all backgrounds to what is happening to black people.

I say over and over again that the only reason there’s all this miscommunication and misunderstanding is that people don’t understand who we are.

They don’t understand that the food we eat is the food they eat. We all eat melon, we all eat chicken, so why is melon and chicken associated only with black people?

A moment of stillness shot while on assignment in Mound Bayou, Mississippi: the first all-black town in the US.

We have always been crying for some reason or another and speaking out about what is happening to our community.

But with the advent of photography – and more recently social media – we have been able to show unequivocally what is happening to black men in our neighbourhoods.

The people I photograph are a living testimony to an ongoing struggle. Somebody recently told me, ‘One of my goals is to figure out what this life means.’ My response to her was that this life means nothing to us.

As the present generation, we draw from the work of previous generations to get some sense of what we’re doing here.

Our role is to continue the struggle, so that 20, 30, 40 years from now, that generation has a better understanding of what we’re supposed to be doing.

I’m just following the rules and the path that were laid down by my ancestors and everyone else who came before.

I’m doing the best I can today in the the hope that subsequent generations will have a better idea of how to move this stone forward.

This article appears in Huck 57 – The Documentary Photo Special IV. Subscribe today so you never miss another issue.

Check out the portfolio of photographer Ruddy Roye.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.