A teen's visual diary of the early-90s rave scene

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Simon Burstall

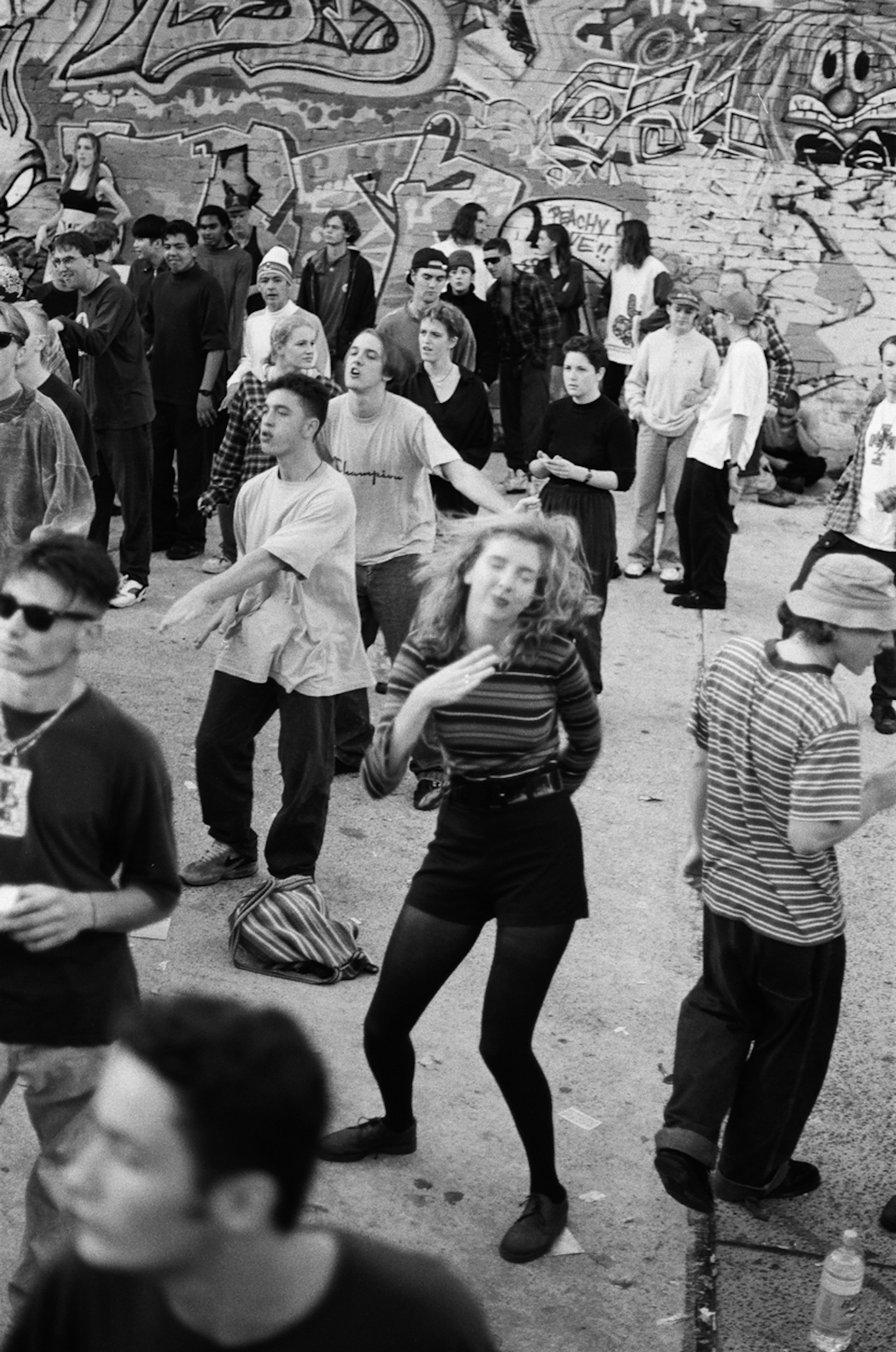

Simon Burstall keeps having flashbacks. Nearly every day for the past year, memories of thumping raves – the ones that shaped his teenage years – keep catching him off-guard.

It could be a car park packed with loved-up strangers still dancing at 10am; train stations filled with light so piercing that it could rip through your eyeballs; the smile of a DJ who died way too soon; old people shaking their heads at the waste of youth.

The Australian has been busy making a book about that time, so it makes sense that these scenes have been coming back to life. But even when he’s busy doing something else entirely, the echo of a moment will announce itself with a rush of goosebumps.

“Truth be told, it’s pretty great,” says Simon, now a 43-year-old photographer living in upstate New York. “I clearly remember standing on a set of speakers, holding an intimidatingly large camera and thinking: ‘This is special.’ Being part of a family and a subculture that was so unique made me feel like an insider looking out, rather than an outsider looking in.”

In 1992, Simon left his surf-side community in southern Sydney for a boarding school in the city centre. That’s where two discoveries would transform how he saw the world: raves and photography. At that point, the 15-year-old had struggled at different schools – “I was never a bad kid, I just always questioned things” – but this change of setting didn’t bode well.

He contracted a bad case of glandular fever just before enrolling, meaning he started a month later than his classmates: a mix of country boys and rich kids whom he struggled to connect with. “I had the shittiest room in the dorm, right by the door, where it was cold and draughty. I remember crying at night – and I’m not much of a crier – but that’s how tough a time it was.”

Simon’s saving grace was an art teacher who encouraged him to borrow various cameras and take as much film as he wanted. It inspired him to make the most of boarders’ weekly taste of freedom. He’d go home to see his family on a Saturday and, later that night, would have a bunch of old mates stay over in his parents’ backroom.

Together they’d get up at 3am and drive out towards the warehouses of Alexandria, 4km south of Sydney, honing in on whatever rave they’d discovered that week through a flyer with a phone number on it. They were shrewd enough to know that nobody would be checking tickets by that point, meaning you could “spend your money on other things and dance the morning away”.

“It was pretty heavily underground – there were no cops and security could be dodgy as well – but it was still a wonderful haven and provided some of the best times of my life, even though it probably didn’t help my immune system,” he says. “There was this sense of united respect and a feeling of, ‘We’re just all one happy family here.’ I didn’t see any fights. At all. Ever.”

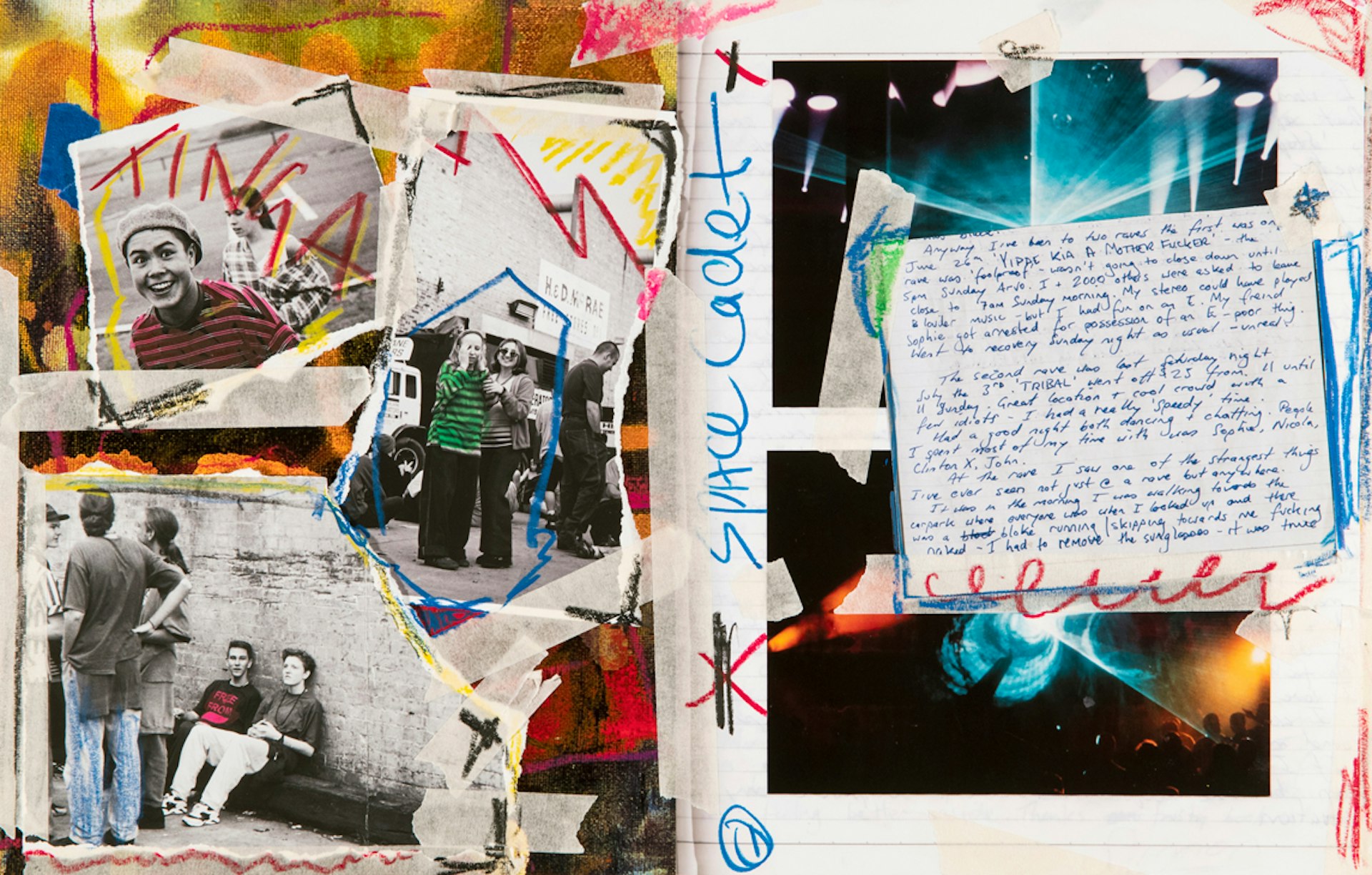

Come Sunday night, Simon would get dragged back to boarding school. But maintaining this routine helped build towards something unexpected. The teenager kept a private diary of observations – “It was a way of processing everything” – as well as a visual portfolio that formed part of his coursework.

If he wasn’t crashed out in the school hospital, Simon would spend every moment developing film – be it during break time or after class – so he could perfectly preserve the ups and downs of that time.

“I want to talk with a counsellor or someone to that affect [sic],” reads one entry. “But all they would say is, ‘Stop drugs and your life will come back together.’ But I don’t want to stop – I love them all, from the pot to the speed to the Es.”

One night, having spent years immersing himself within rave culture, Simon took way too much ecstasy laced with ketamine. He remembers waking up in a field just as dawn broke, gasping the words “Fuck me!”

The music had stopped and an older man in a white buttoned-down shirt was on stage, informing everyone that he was from the town council and that it was time to go home.

“It was bad,” says Simon, the pitch of his voice dropping somberly. “There were two fatal accidents that day and suddenly raves were on the front page. The secret was out. I think once that happened, it all became too cookie-cutter and never quite recovered. Meanwhile, my body went, ‘Okay, enough’s enough. You’re going to have to keep it together here and move on with your life.”

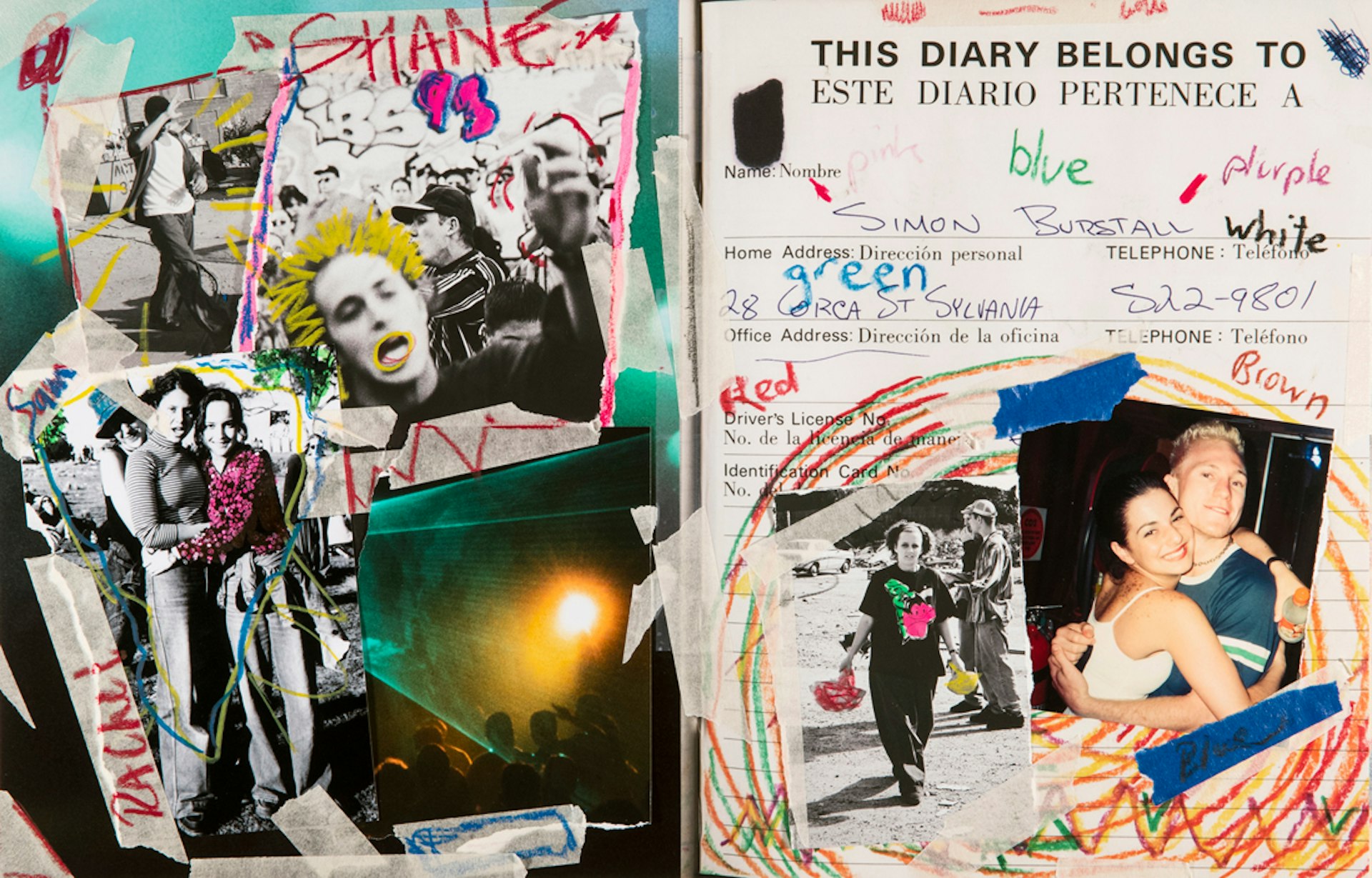

In August 2016, just before Simon’s parents sold the family house, he asked them to gather everything he’d kept from the ’90s and pack it in a suitcase: the diary, the flyers, the negatives. He wanted to reabsorb it all from the vantage point of experience, 25 years later, and assemble the most evocative moments in a book. That proved much harder than expected.

“I was unfiltered back then,” he says. “Going through the diary felt so hard because I was 16 and either drunk, high or emotionally on edge. A couple of times I thought, ‘This is too much. I can’t… I don’t know where this is going.’”

After finishing school, Simon began working as a photo assistant and moved to New York in 2000 to pursue a career in commercial photography. Today he has two kids, aged one and three, and is a joy to speak with: infectiously buoyant and curious. Maybe it’s the impact of revisiting this period in his life, but there’s a spiritedness to him that makes it feel like you were right there as all this unfolded.

Lately, he’s been reconnecting with people in the photos whom he hasn’t spoken to in 25 years, while also planning release parties for the book [titled ’93: Punching the Light] in NYC, Sydney and Berlin. This is the first interview Simon has given and it’s clear he’s still processing what it means to him.

“It’s been an education,” he says. “The school, the art teacher, the photography, the raves – I can see now how it all helped me. Picking up a camera gave me confidence and launched me into being an adult. Once I fell in love, moved on and grew up, I stopped writing the diary.

But falling deeper and deeper into this project has convinced me that it’s an era that won’t ever be recreated. It was like an oasis that happened for three years and then it was gone. And god, it was so much fun.”

’93: Punching the Light will be published by Damiani on 26 September. RSVP for the parties here.

This article appears in Huck: The Burnout Issue. Get a copy in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.