Capturing the eerie voices of old spy radio broadcasts

- Text by Biju Belinky

- Photography by Lewis Bush

Human beings love secrets: That’s a fact. If you want proof, you only have to look at the hours people invest on debating conspiracy theories online, be it about Avril Lavigne’s body double, the Chupacabra or CIA mind control. But while the aforementioned discussions might seem a bit far-fetched, numbers stations are just as mysterious – and very much real. They are living secrets, without clear owners or operators, existing and broadcasting into the void endlessly.

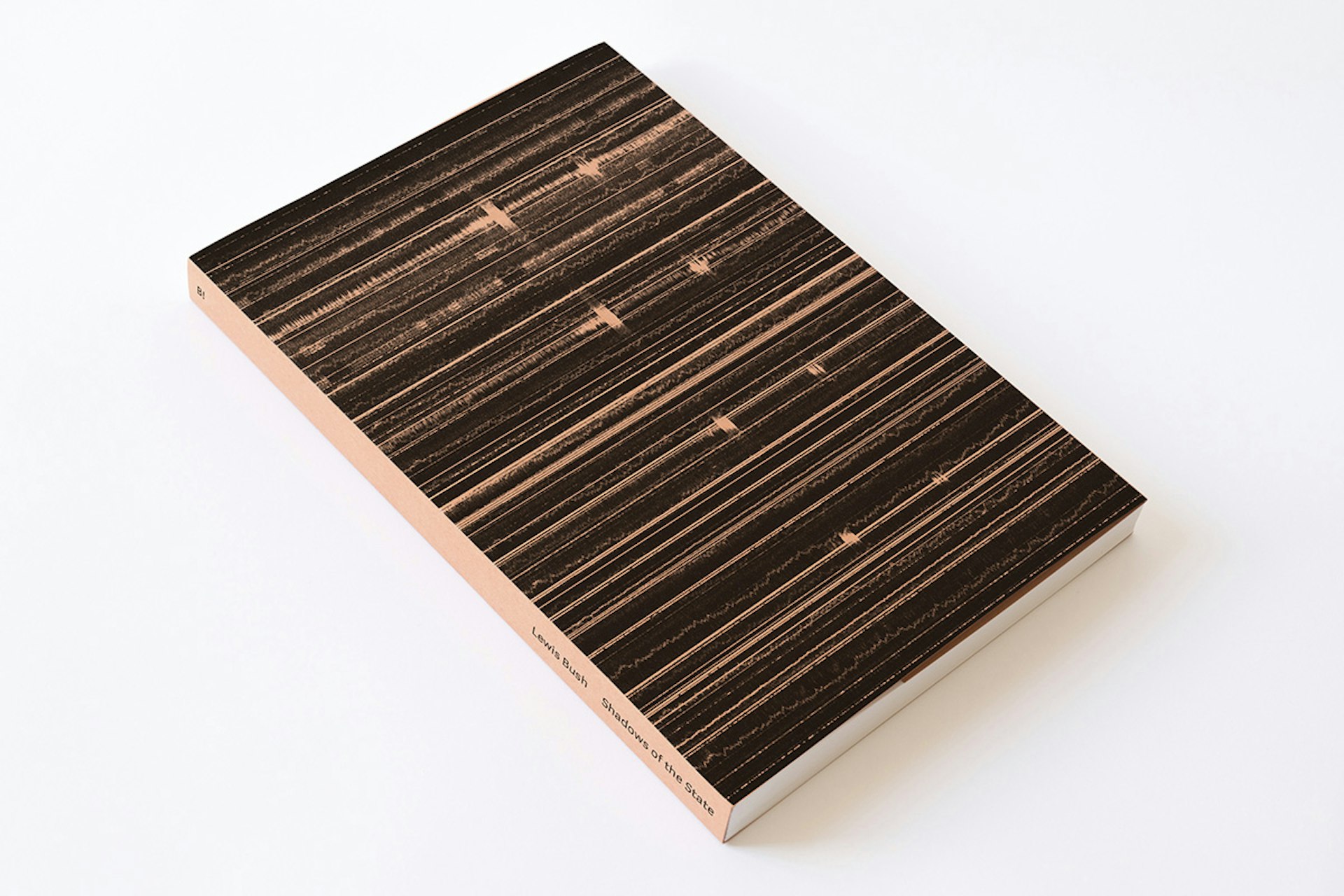

“Numbers stations are shortwave radio broadcasts usually consisting of computerised voices reading strings of seemingly random numbers,” explains Lewis Bush, author of Shadows of the State, a photography book cataloguing these mysterious broadcasts and where they stem from. “They have existed since at least the Cold War and possibly earlier, but their owners and operators remain for the most part a mystery.”

Operating like pirate radio, without any fixed frequencies, these radios are thought to have been established in order for secret intelligence agencies to send information to their agents out of base. And although their popularity might’ve dimmed, there are still plenty of active stations in places like Cuba, Russia and North Korea.

Drawn by the way these strange historical sounds seemed to loom within our reality unperceived, Lewis set out to discover both the recordings and their receivers, spending time talking to the communities of people who dedicate their time to analysing these broadcasts and attempting to capture the immaterial.

The result is Shadows of the State: A photo book currently being crowdfunded on Kickstarter, registering thirty receivers of these stations, their locations, their recordings and radio waves. We spoke to Lewis Bush to find out more about the project.

V07 Spanish Lady

What were some of the most surprising discoveries you’ve made while researching for Shadows of the State?

Lewis Bush: I encountered some strange stories in the archives which were fascinating but which didn’t really fit into the main project. One I like is about a radio station called Gustav Siegfried Eins, which was active during the Second World War. It appeared to originate in Europe and the announcer seemed to be a disaffected German army officer, who spent his time on the air spreading lurid rumours about Nazi officials. In fact, the station broadcast from England, and was run by a refugee from Germany working for the British Political Warfare Executive, effectively a psychological warfare unit. The station’s transmissions ended with a dramatic episode where the Gestapo appeared to stage a raid on the station during a live broadcast, it was all completely dramatised of course. I also read some strange stories of research into psychic spies, and came across a huge amount of stuff that was surprising because it was so banal, like a huge CIA study conducted to investigate the number of car parking spaces they had available at their headquarters.

Considering this is quite an abstract subject, did you find it challenging to find a way to visually convey these “shadows”?

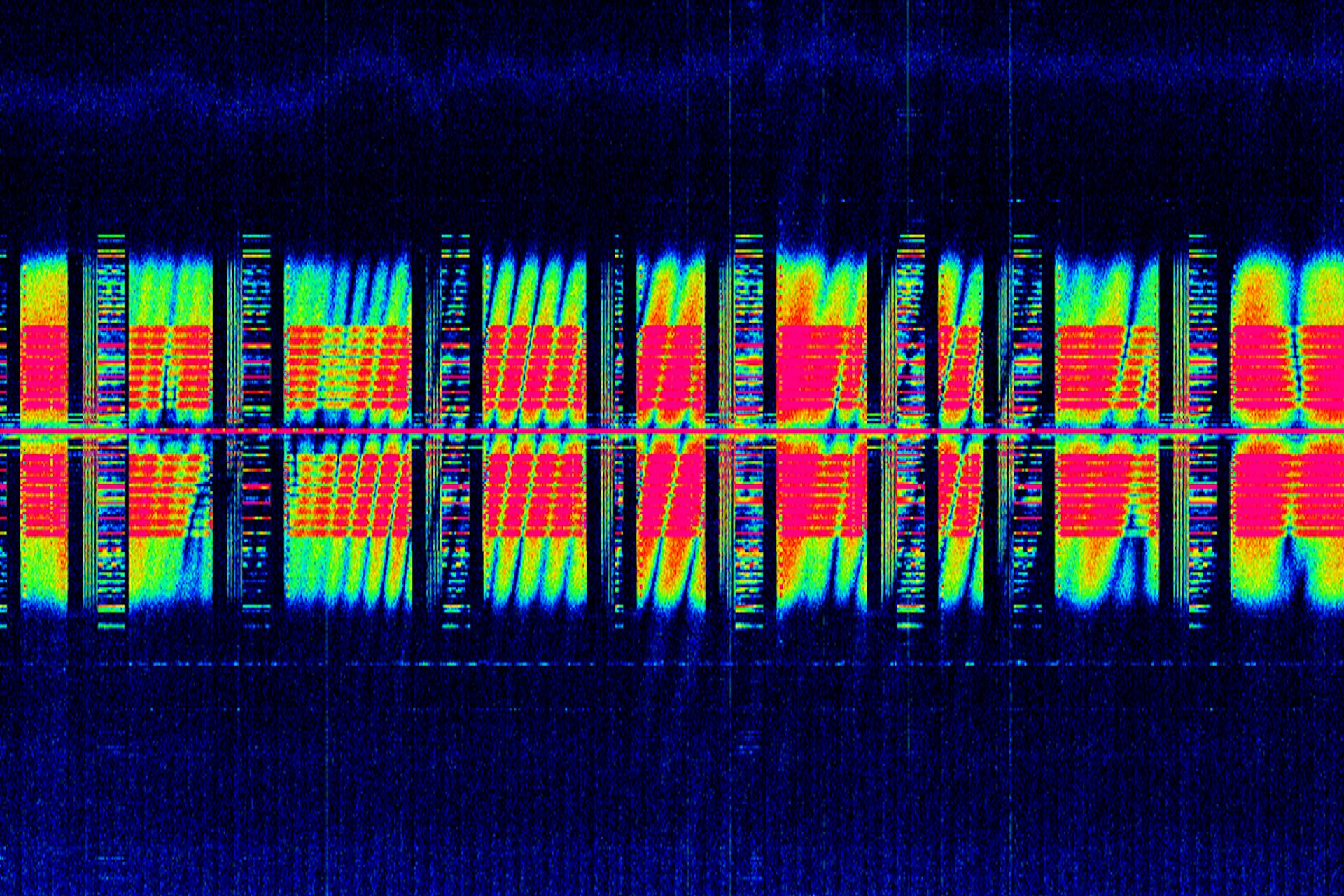

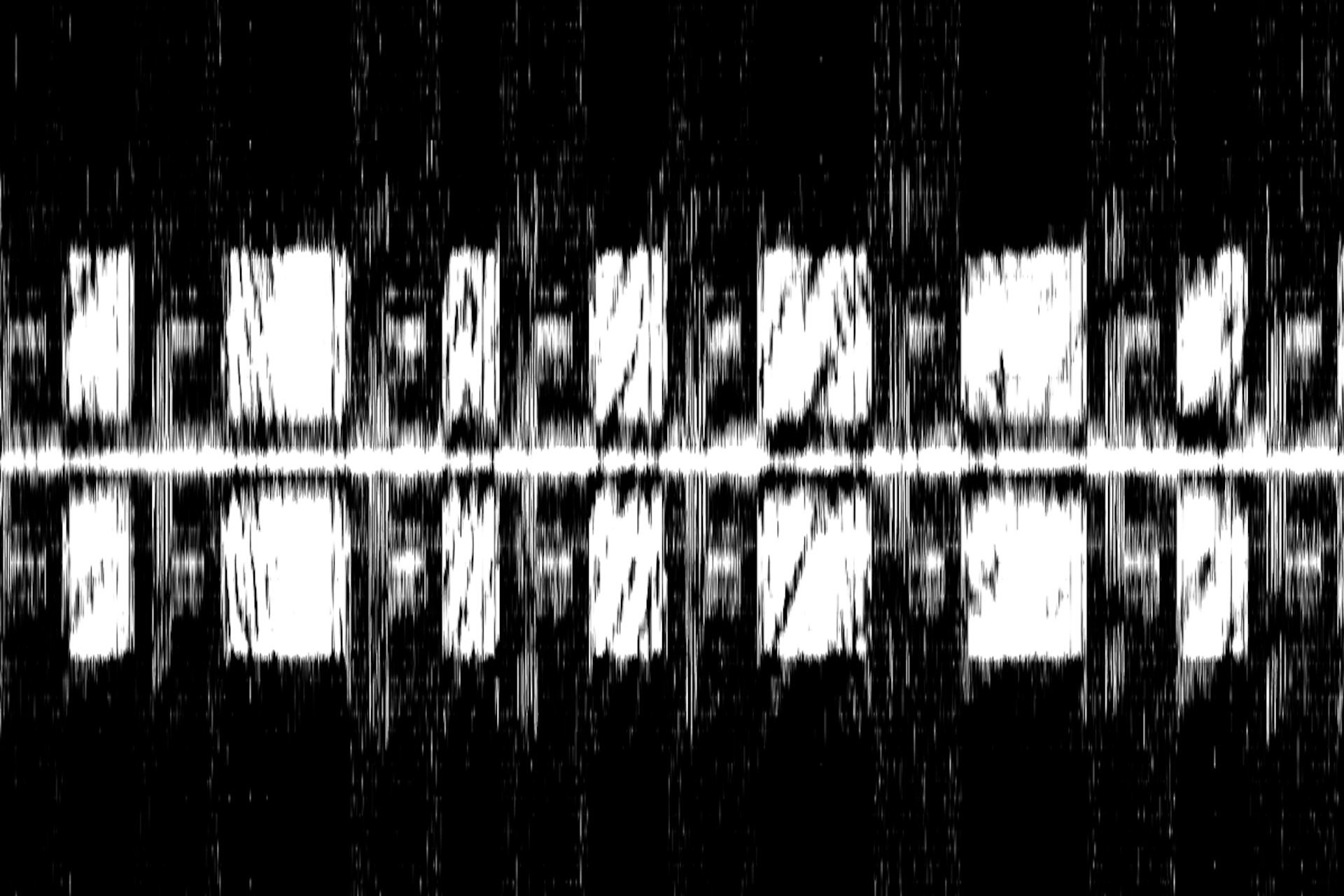

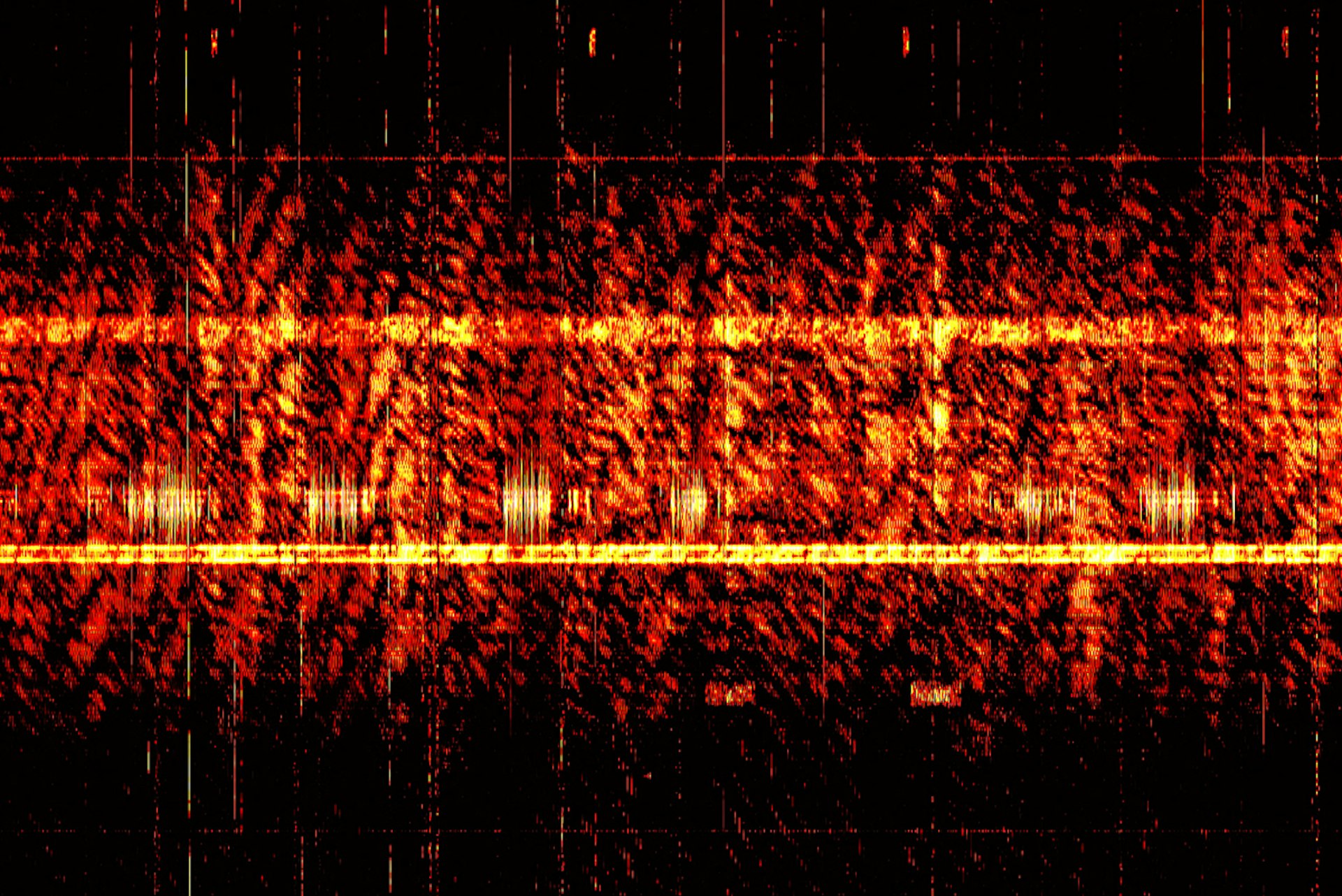

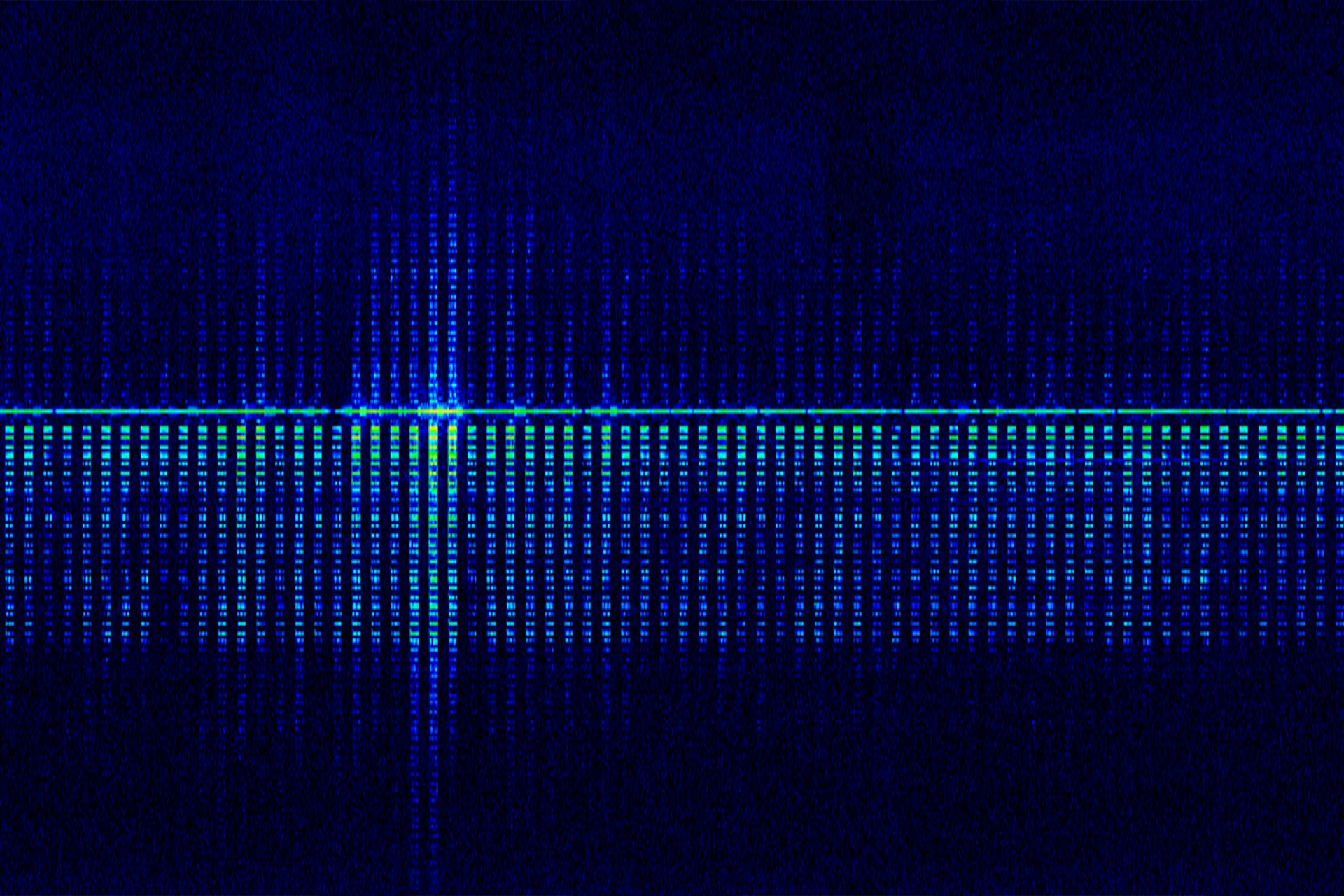

A key part of the project was discovering the possibility of making images of the signals themselves, using spectrograms produced by shortwave radio software to visualise them. I’m very interested in the idea of finding ways to make abstract subjects visible, so this was a bit of a breakthrough and the strange images that resulted seemed like a good accompaniment to the more conventional satellite maps. I like to call these spectrograms photographs in the sense that they are making visible a form of electromagnetic radiation on the same spectrum as visible light, so if you think of photography as literally writing with light, that’s what these images are also doing in a sense. People sometimes have a hard time accepting that idea, but I think it’s interesting and important to try and expand what we think of as ‘photography’.

Warrenton, Virginia

RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus

What do you think makes humans historically fascinated with codes and secret messages?

I suppose it’s a sense of the unknown and unknowable. The thing I often compare listening to these stations to is the feeling of looking down into very deep water, where you can’t see the bottom. You know something is down there, but you have no idea what, and the process of trying to find out is tinged with risk. These coded messages might contain sinister information, they might be completely benign, it is unlikely we will ever know. There is something compelling about the knowledge that these signals are completely opaque, their messages unknowable.

Do you have a “favourite” station in the book?

That’s hard one, they are so diverse and bizarre it would be hard to pick out just one. It’s perhaps a rather obvious choice but there is one called the Lincolnshire Poacher which is thought to have been operated by the British intelligence services and transmitted from a site in Cyprus. The name of the station comes from a tune it plays at the start of its transmissions. The tune is an electronic version of an English folk song which tells the story of an apprentice from Lincolnshire who gives up his vocation to become a poacher. The lyrics are all about chasing hares by moonlight and avoiding gamekeepers, so it’s an apt song for spies and suggests the person who picked it might have had a bit of a sense of humour when they chose it. The other great thing about this station is the voice used for the numbers, which is totally British and sounds just like the continuity announcers you hear on BBC radio.

Spectrum 7, waiting

Shoal Bay, Australia

What was the process of tracking these stations down like? Were there any that were absolutely impossible to find?

The process usually involved reviewing everything I could find about a particular station. That would hopefully start to suggest a country of origin, or perhaps some more specific location. From there I would cross-reference specific information about a station with more general information about covert transmitter sites and other installations associated with intelligence gathering in the country I was interested in. Gradually this would help me focus in closer and closer. In some cases, I would be able to identify the actual site quite quickly, in other cases it would involve searching a particular area for a suitable transmitter site, then trying to find out more about its uses, and so on. So some locations in the book are much more definite than others and that’s one of the things I discuss in the texts. There were definitely stations I couldn’t find, generally, the newer ones are the hardest to locate because there is the least information on them. Another factor is that information on stations is more readily available for numbers stations broadcasting in locations like Europe and North America because the numbers station listening community has tended to be more active in these regions.

Falenty, Poland

S28 The Buzzer

You’ve worked a lot with abstract historical concepts – how did that interest start?

I originally studied history before working in international development and then later retraining as a photographer, and I think coming from that background has very much informed the subjects I make work about and the ways I want to explore them. One of the problems I think with much documentary photography is it tends to focus on things which are very evidently visible and can be captured by a camera in a very conventional way. The downside of this is many topics and issues go unexplored, and I think the responsibility of photographers and the challenge facing them now is to find ways to bring these abstract subjects into view. We can’t keep reusing the same old methods endlessly and uncritically. So I have often tried to approach quite abstract subjects, whether that’s been looking at the role in modern history in the Euro crisis, or trying to critique the use of unpaid labour by successful artists.

How do you think the past can help us understand the present?

As time passes many things change, but the fundamentals remain mostly the same. I think the past is regarded as important in so many cultures because it is recognised as a way we can understand continuities in our present and determine the right responses to the challenges we face right now. The Cold War, with its nuclear brinkmanship and often irrational leaders, offers clear lessons for today’s world when the possibility of conflict between nuclear-armed states seems to be becoming ever more real. Understanding the past can also help us understand and humanise the people we sometimes perceive as enemies. I recently read Svetlana Alexevich’s epic oral history Second Hand Time, which documents the collapse of the Soviet Union through the words of Russians who experienced it. Perhaps more than anything else I have ever read this book helped me to start to understand why Russia and the West find themselves in such an adversarial relationship today.

Shadows of the State by Lewis Bush is currently being funded via Kickstarter.

Biju Belinky is Huck’s staff writer. Follow her on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.