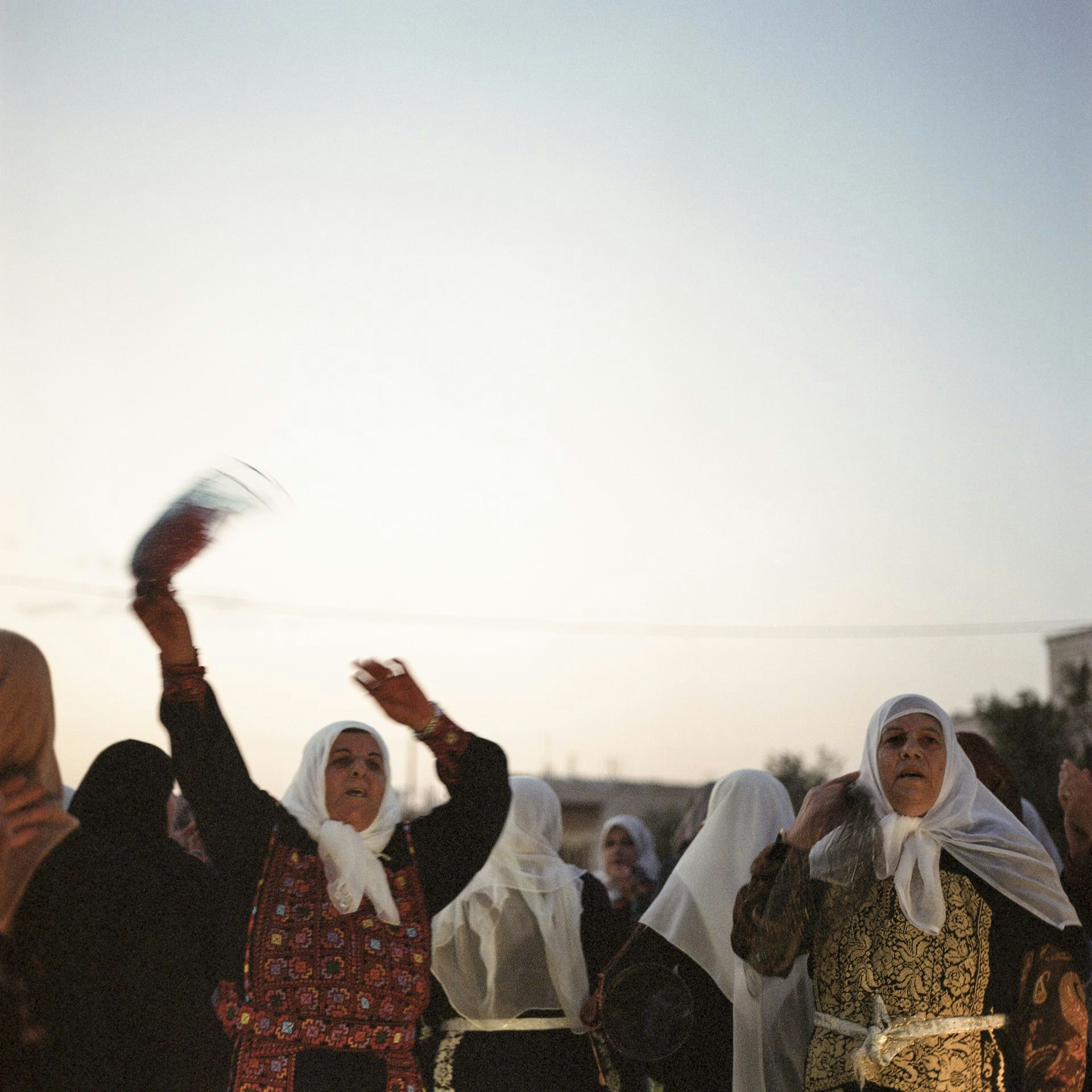

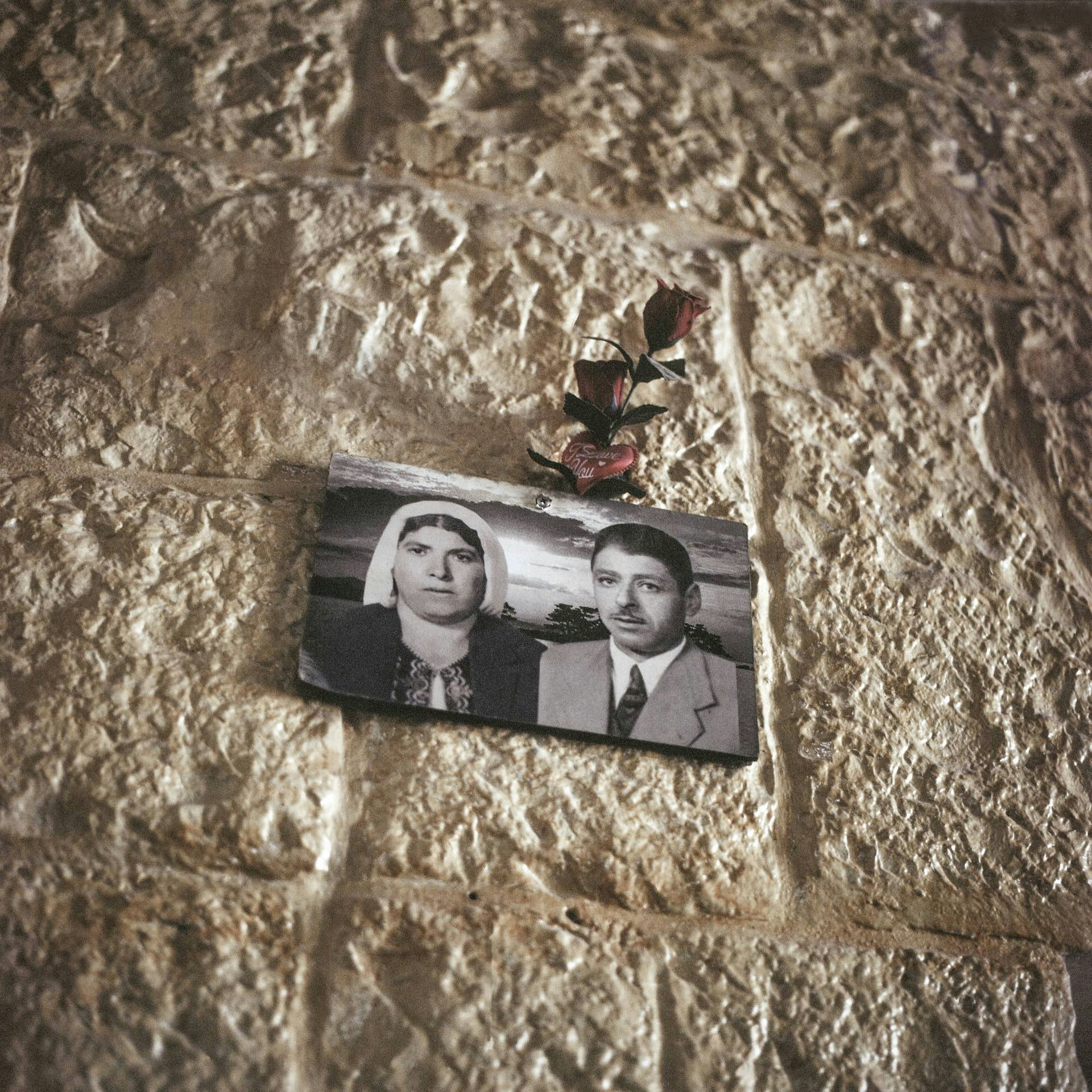

The quiet resistance of a Palestinian village

- Text by Eva Clifford

- Photography by Pauline Beugnies

Situated in one of the world’s most volatile regions, the Palestinian village of Battir occupies a unique position in the West Bank.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, when most residents had fled Battir, a man named Mustafa Hassan and several others stayed behind, lighting candles in the houses at night to make it look as though the village was inhabited. They did this in the hope that it would prevent an attack from the Israeli side.

Hassan then negotiated an agreement with the Israeli Defence Minister about the demarcation line – known as the ‘Green Line’ – which runs directly through the village, maintaining that if the inhabitants of Battir respected the Israeli railway line they would not construct a border. The agreement has stuck ever since, and Battir remains one of the last Palestinian villages that is not yet cut off from Jerusalem by the separation wall.

“The situation of Battir is quite unique in the West Bank as inhabitants can cultivate and access their land over the Green Line, the only official and internationally recognised border that marks the Armistice line following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War,” says Belgian photographer Pauline Beugnies, whose project Battir, The Green Intifada focuses on the region.

Beugnies was studying Arabic in Cairo, Egypt – where she lived for five years – when she befriended Hassan Muamer. Hassan was studying engineering in Cairo at the time and Beugnies remembers how he used to proudly show her videos of his hometown, Battir. Although Beugnies had been to Palestine a couple of times before, she visited Battir for the first time in 2010 with him, before revisiting later that year with her mum and sister. By that time, she knew she wanted to do a story there.

“The land conflict in Battir is so clear, yet subtle,” Beugnies tells Huck. “It’s not obvious like the wall in Bethlehem, but in Battir there’s something more human about it and I guess the resistance is also greener, so it’s very peaceful.”

Shortly after her second visit, the Egyptian revolution began and Beugnies was preoccupied with documenting the unrest there. Returning to Battir several times as both traveller and photographer, Beugnies found a deeper attachment to the place, and soon began forming her own relationships. This was helped by the fact she’d been studying Arabic.

“I was not so good after a year at school, but thanks to being a photographer, I’m always hanging out with people so I got to learn the language that way – with the course then with the practice,” she explains.

“I spoke Egyptian Arabic, which was really funny for the people there. I think they liked me more for that because I was this white girl speaking Egyptian Arabic. So I connect with people like that, but of course, in the beginning, I was with Hassan so I had the best guide and he was introducing me to people. I was staying in his home so it’s very different. I was not a stranger, I was half a stranger, let’s say.”

At the time, the inhabitants of Battir were fighting for the protection of the region’s ancient olive groves, terraces and irrigated gardens that make it such a unique place. Eventually, they won the fight and in 2014, Battir was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Beugnies says that while the land is largely unused as inhabitants are forbidden to build on it and trade like they used to, there is an influx of visitors. Residents – along with the Ecological Museum, a citizens’ initiative – are now working together to encourage sustainability and organise hiking trails. They believe that if the land is used by Palestinians, it will be more difficult for Israel to purchase or confiscate parts of it to build the wall or expand Israeli settlements.

“What was really beautiful for me to see was that this initiative came from the people, to the people,” says Beugnies. “It found the support on an international level afterwards, but the spark, the energy, the will came from the people.”

“If you look back, the first time I went in 2010, almost nobody was going there and now almost 10 years later people are going there, so they successfully managed to make Battir a place that you visit when you go to the area.”

Shooting on Hasselblad, Beugnies had the benefit of slowing down to match the gentle pace of village life. Through her intimate access, we see a different side to the conflict – one that is strikingly at odds with the typical scenes of violence that dominate media coverage of the region.

“I could feel that people were proud of being from this village; they were ready to resist and the village was about to win a big fight against the wall being built there,” reflects Beugnies. “That all happened when I was taking pictures there. You can sense this quiet resistance, a way of saying, ‘We are here, we are not going anywhere. This is our village and this is the beautiful place we live in,’ and I hope this somehow comes through in my pictures.”

See more of Pauline Beugnies’ work on her official website, or follow her on Instagram.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.