A visual celebration of Native American culture

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by The Seattle Museum of Art

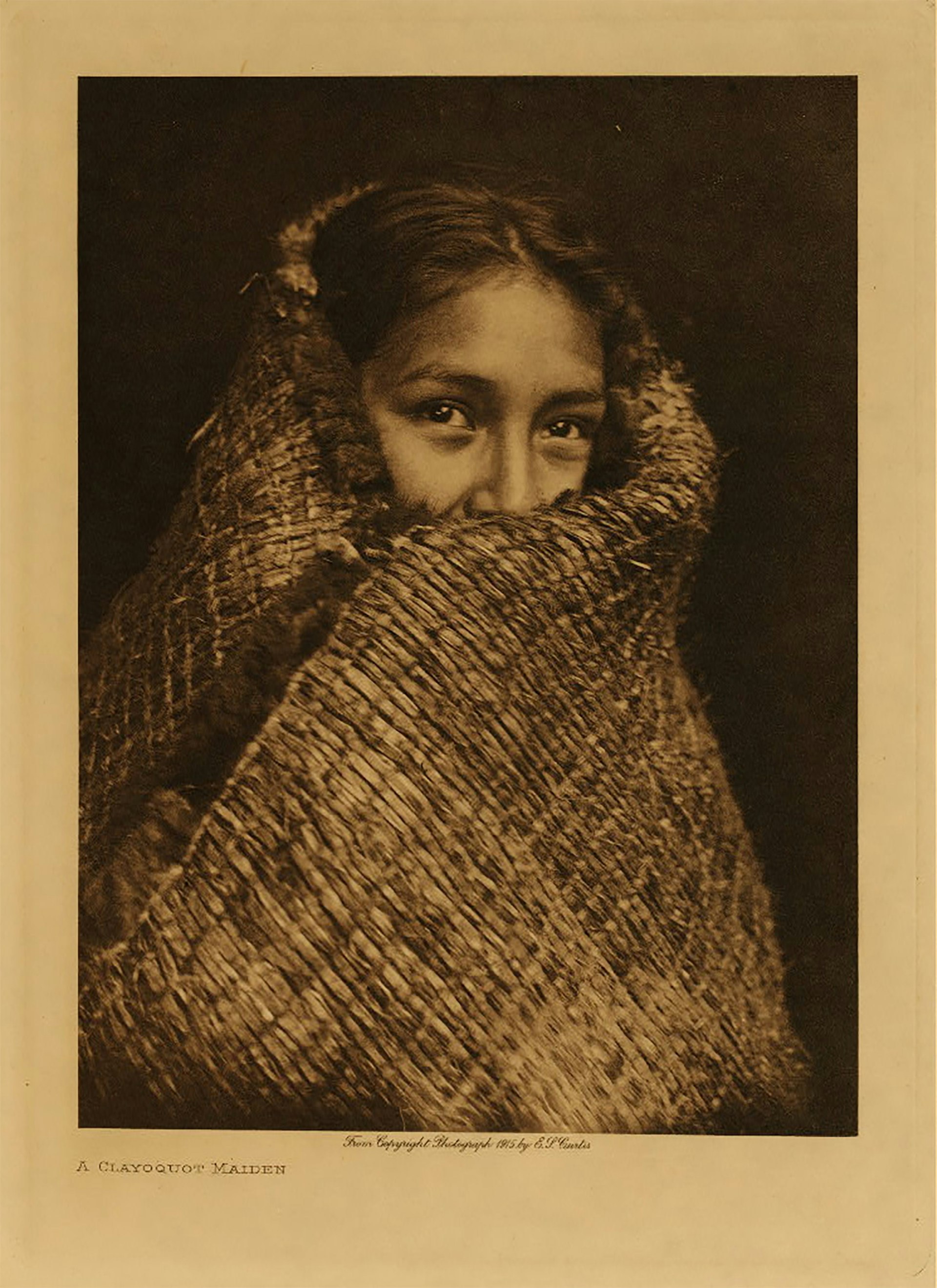

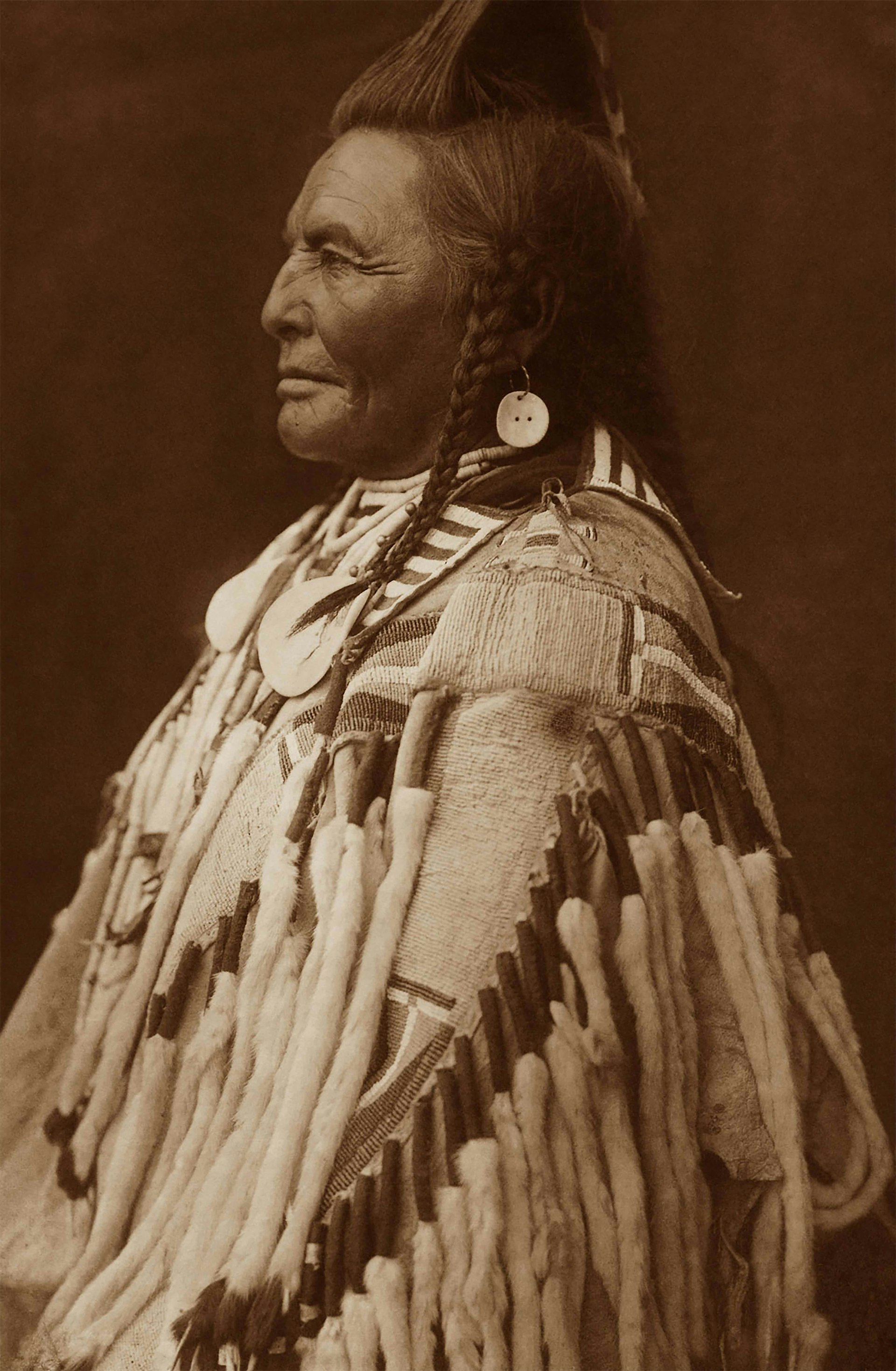

In 1895, Edward S. Curtis took his first portrait of Princess Angeline, daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. The image marked the start of what would be the most widely recognised photography project documenting the First People of the North America – a group who were literally vanishing off the earth.

Double Exposure, now on view at the Seattle Museum of Art through September 9, 2018, presents the work of contemporary Seattle-based Native artists Marianne Nicolson, Tracy Rector, and Will Wilson, each of whom create original works that engage Curtis’ legacy in dynamic new ways, that reveals its strengths and weaknesses as documentary work.

“With Curtis, you see a history that is terrible laying just beyond these photographs that he excised from his version,” says Barbara Brotherton, Curator of Native American Art. “So while he is on reservations from 1901 and 1927, he is witnessing Native peoples struggle under deep colonial oppression. Children as young as four years old being ripped from their parents and sent to boarding school – and that is nowhere to be seen.”

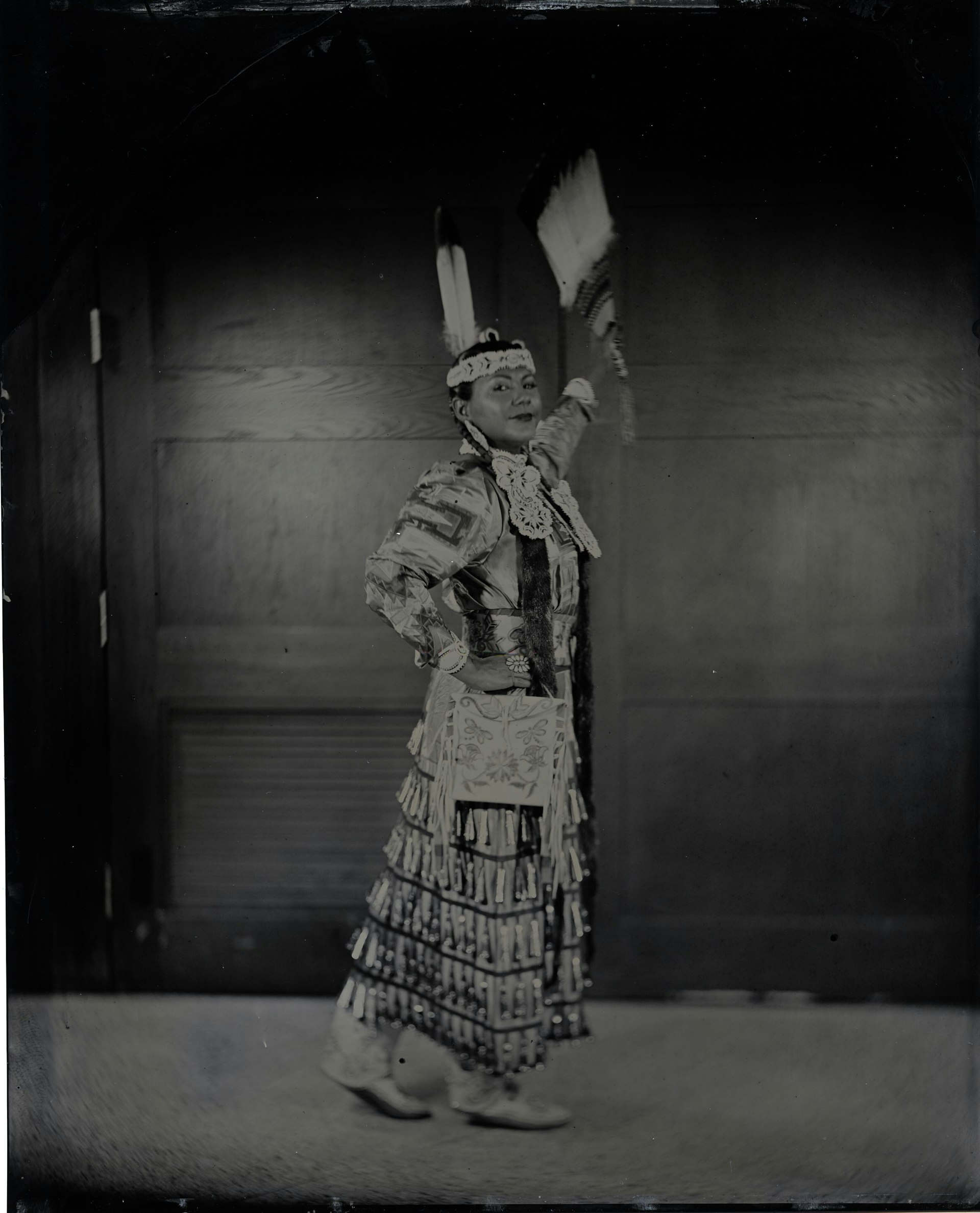

Talking Tintype, Madrienne Salgado, Jingle Dress Dancer/Government and Public Relations Manager for the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, Citizen of the Muckleshoot Nation, 2017, from the series Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, Will Willson.

“People say that the camera was just another way of oppressing and categorising Native people so that they would always be seen as inferior. These young voices are trying to explore all those things. Native people know that whole history. Their ancestors told them. It’s only 100 years ago.”

Each of the artists featured in the exhibition add a vital history that has not yet been told, one that documents Native American culture from the inside, with an understanding of the lives and legacies being revered and preserved.

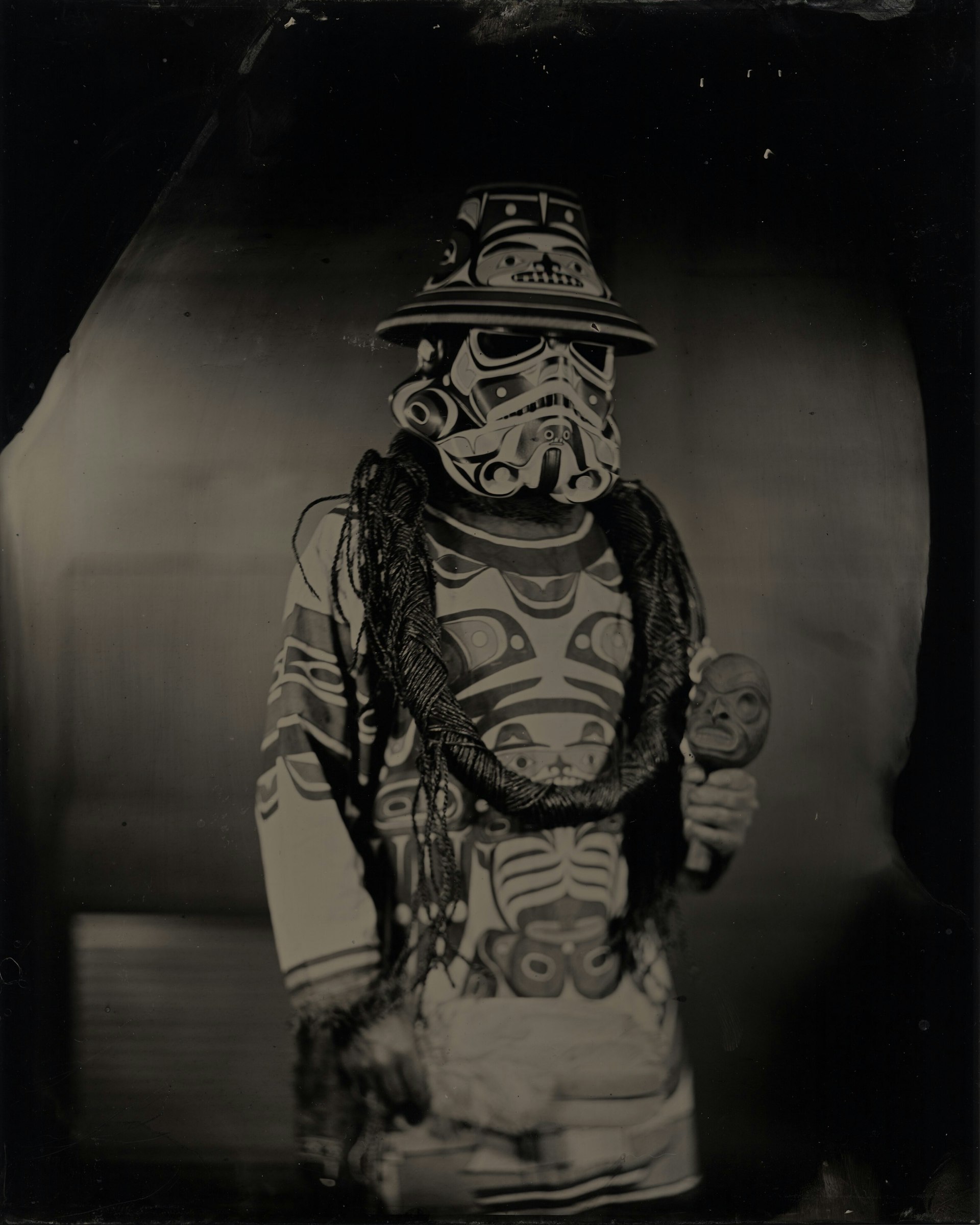

Since 2012, Dine photographer Will Wilson has been making tintypes of Indigenous artists, educators, and activists for his series Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange. The exhibition features 11 portraits of local Seattle residents, many of whose families arrived in the region during the government relocation projects of the ’50s and ’60s. The result is a series of portraits of a community who are alive and well, whose energy and vitality glows in each print.

Chockton/Seminole artist Tracy Rector uses film to expose what is missing in Curtis’ telling of Native life. Working with at-risk youth from Indigenous communities, Rector gives them a digital camera, so that they started telling their own stories.

Tracy Rector

For the exhibition, she created two videos that run on opposite walls. Clearwater: People of the Salish Sea is a black and white video made with drones that documents a series of waterways that connect Seattle to Canada. Ch’aak’ S’aagi is a colour video with vignettes of Native people telling stories about their lives on this land, revealing how the intersections between geography and exchange have brought about a revival of Indigenous culture during our present day.

For Marianne Nicolson, a member of the Dzawada‘enuxw First Nation of the Kwakwaka‘wakw First Nations in British Columbia, the connection with Curtis’ work is personal. It is her relatives who appear in Curtis’ 1914 film, In the Land of the Head-Hunters. For Double Exposure, Nicolson has created Ḱanḱagawí (The Seam of Heaven), a series of 12-foot-tall light sculptures that case long shadows on the floor, examining the histories and cosmologies of Indigenous life on the waterways.

“The work of these artists stands in sharp juxtaposition to the elegant Curtis photographs with their romanticised approach that casts Native people in the past,” Brotherton concludes. “Native people did not vanish. They are resilient and deeply engaged in the issues of identity today.”

Will Willson.

Tracy Rector

Stormtrooper, Will Willson.

A Clayoquot Maiden, Edward S. Curtis

Talking Tintype, Tracy Rector, Artist/Media Activist, Citizen of the Choctaw Nation, 2017, from the series Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, Will Willson.

Tracy Rector

Shot in the Hand—Apsaroke, Edward S. Curtis

Homeward, Edward S. Curtis

Double Exposure is on show at the Seattle Museum of Art until September 9, 2018.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.