Dennis Morris

- Text by Josh Jones

- Photography by Dennis Morris

Dennis Morris came of age documenting the changes that surrounded him. Born and bred in Dalston, Hackney, his observational lens on life later proved iconic when he captured the likes of Bob Marley and The Sex Pistols off-stage and in their prime.

Found and encouraged at a photography class put on at his local church by philanthropist and inventor of photographic equipment Donald Patterson, he was heavily influenced by war photographers like Robert Capa, Don McCullin and Eugene Smith as well Tim Page and Gordon Park – the first black photographer to work with Time and Life magazines.

His vast body of work – including Growing Up Black and Southhall: A Home from Home, which explores Asian identity in Britain – gives a rare documentation of the UK in flux during the 1970s, as new communities flourished and the youth embraced culture from all angles.

Can you remember first getting published?

The first time I got published was a bit of a tragedy. I had a cover of the NME and I think Melody Maker, both at the same time with shots I did of Bob Marley at The Lyceum. I rushed to Mr Patterson’s office, asked if he was in and they said, ‘Have you not heard?’ He had died on holiday in Scotland. He was walking around a loch and some kids had got into difficulty. He went in to save them and they all drowned. So he never got to see my covers. It was a bittersweet moment for me.

You were one of the first people to document inter-racial relationships in the UK. What drew you there?

Yeah, in my book Growing Up Black there’s an inter-racial marriage with a twist. In those days it would have been likely to be a black guy marrying a white girl, but one I shot was a white guy marrying a black girl and what is funny in those pictures is the division between the families – the only happy people in the picture are the couple. I was about fourteen when I did that. I just saw it as a way of practising my art and my technique.

Were you aware that you were capturing a significant era of social change?

I knew what I was doing was good and I knew what I was doing had a place in time, but in terms of extent what it’s become, you can never really foresee that really. If you’re thinking about what you’re shooting then you’re probably thinking about making money and if you shoot for making money then it will never become of importance. The truth of it is, when you’re in the shit you don’t really see the shit. It’s as simple as that to be honest with you. It was a really crappy time. We were a generation that didn’t want to be just a part of what our parents had accepted. What I learnt from Mr Patterson was that there was more out there and I had the ability and talent to get more out of it. Then when I met Bob Marley, he told me, ‘You can do it man. They’re always going to tell you because you’re black that you can’t do this or that, but if you really believe in yourself then you can do it.’

Was skipping school to meet Bob Marley the best decision of your life?

Yes. The first time I met him was when he played at Speakeasy Club on Margaret Street. I waited until Bob came up and asked if I could take his picture. He said, ‘Yeah, come in.’ So I went into the club and while they were doing their sound check I took some shots. He asked me what it was like to be a young black kid in England and I asked about Jamaica. He took to me, for whatever reason, and told me about their tour. So the next day I met them at the hotel, got in their transit van and the rest is history.

Shooting the Sex Pistols was a bit like your Everest. They rarely posed, right?

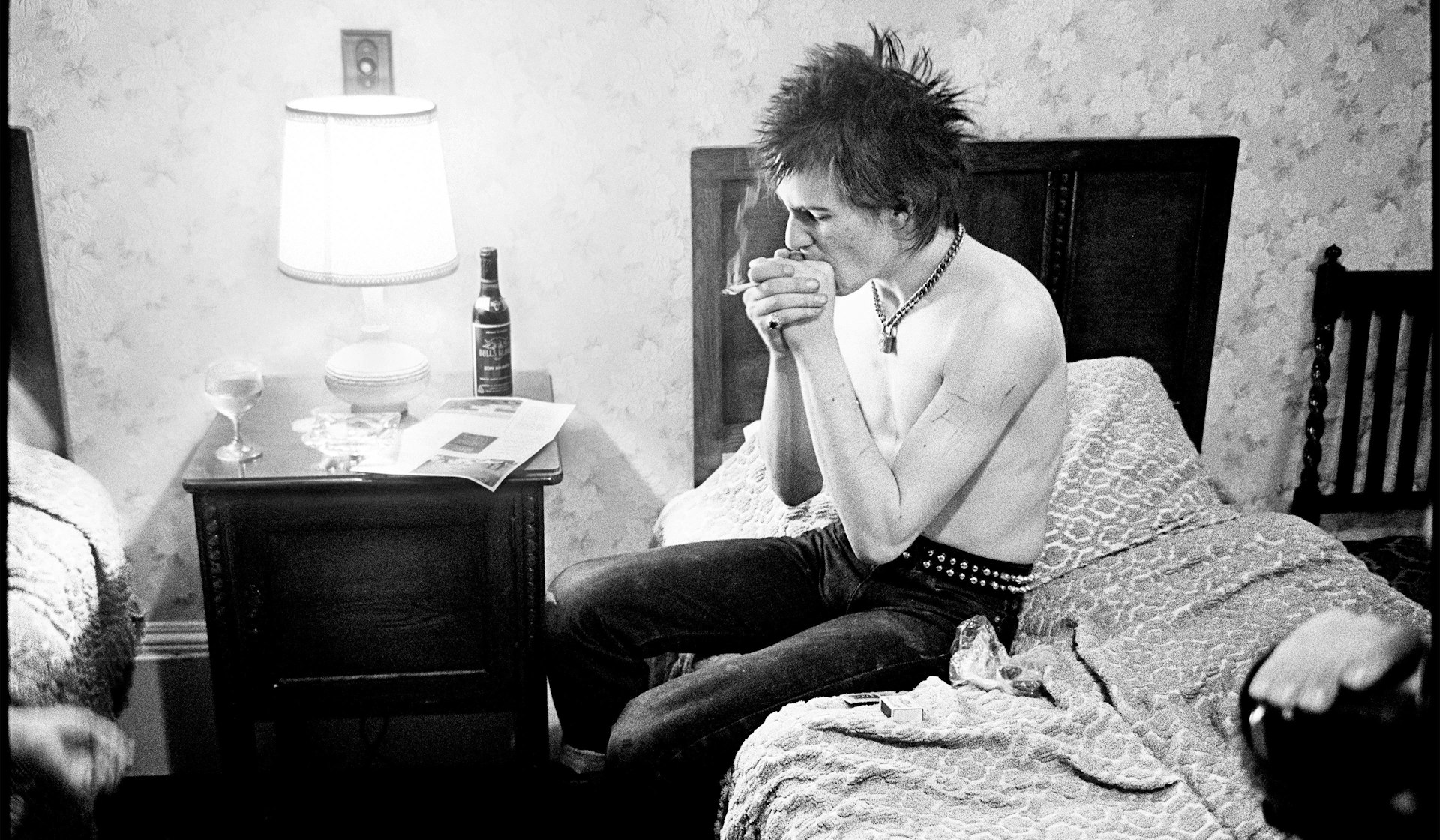

Working with them was a bit of a war zone really. It was absolutely chaotic. The very famous shot of Sid smoking a joint was in Penzance in a room. We were trying to get him off smack [by getting him to smoke instead]. But he couldn’t smoke, he didn’t like smoking. The other famous shot where he completely smashed his room up, I heard all the commotion and when it stopped I went in and it was a nightmare – absolute destruction. For a show I did in December with Shepard Fairey, we recreated that room. Sid smashed the TV that was in the room, so we tried to source a TV from that period. Shepard found one – it belonged to the father of the kid who was on the Nevermind sleeve – and we took it in turns to destroy it. I was smashing the screen and it took about ten attempts with a hammer. Then Shepard did the tube, but what we realised was, my god, the amount of destruction and anger that Sid must have had inside of him!

Your body of work documenting the Asian community of Southall in the 1970s was bought by English Heritage. How did that project come to life?

I don’t know why, but I took a train and got off in Southall. It was like a completely different world, it really was. So I went back again and again and spent maybe a couple of years going there. To do that kind of thing I had to go there in the beginning without my camera. It was mind-blowing for me and eventually I built up contacts with people and produced a camera and started taking pictures. Years later I was doing an exhibition and there was a Sikh man walking around and I could see the enjoyment on his face, so I asked if he liked the images. He looked at me and said, ‘What I want to know is, how did you get through our doors?’ I said I knocked on the doors and said, ‘I’m Dennis Morris. Can I take some pictures?’ I told him I just had that kind of knack. And I do have that knack. I’m able to get through people’s doors.

How did that ‘knack’ help you connect with the likes of Bob Marley and John Lydon?

The technique of reportage demands a one-to-one [relationship] and trust. People have to trust you. It’s a very hard thing to do and you either have it or you don’t. I feel like I’m very lucky to be able to do that. Coming from where I come from in Dalston in Hackney, it’s got me as far away as Tibet. I’ve been up the top of a mountain in Tibet taking pictures.

Has anyone’s advice ever stuck with you?

I read a book years ago by [spiritualist George] Gurdjieff called Meetings with Remarkable Men and it’s all about his journey and meeting people with remarkable abilities. I’ve had that experience throughout my career with remarkable men. I’ve sat down with the likes of Richard Branson. I was actually with him and John Lydon the day he decided to buy Necker Island. We chartered a plane and he pointed at the island and said, ‘I’m going to buy that.’ I’ve been in some incredible situations. Marley was a very, very special person. He had an immense influence on people worldwide. I was very fortunate to sit with him, to talk, break bread, drink, smoke and take pictures of him. None of those images were ever posed. I was just looking, reading the situation, taking a picture and putting the camera down. That’s what people liked about me. It’s been an extraordinary journey.

Catch Dennis Morris’ Sex Pistols exhibition The Bollocks at Known Gallery, Los Angeles, starts Saturday, August 9.

This article originally appeared in Huck 44 – The Tommy Guerrero Issue. Grab your copy now or subscribe to make sure you don’t miss another issue this year.