Yan Morvan: The French photographer who flirts with death for every shot

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Yan Morvan

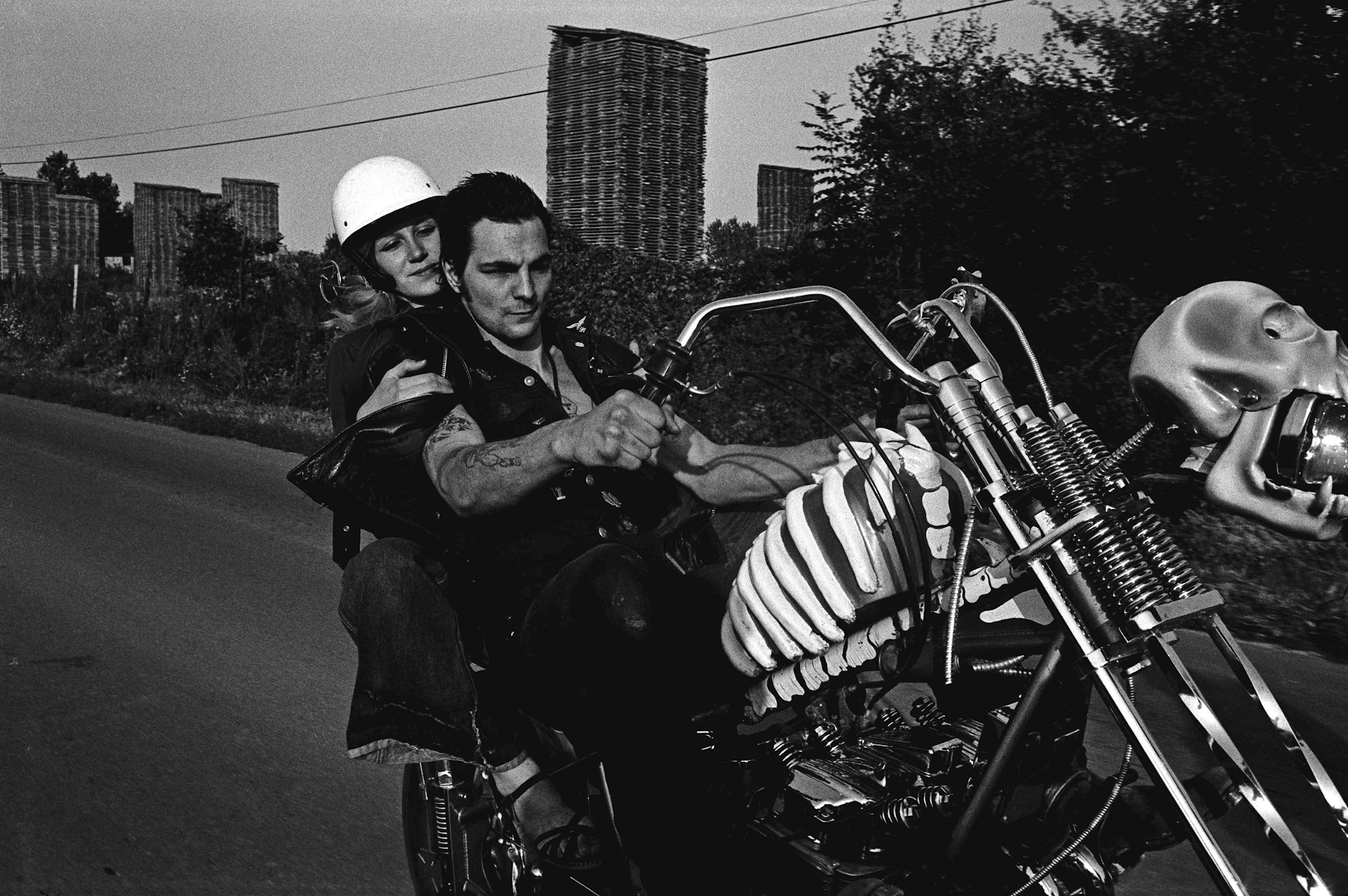

After Yan Morvan published his first photobook Le Cuir et la Baston in 1974, a group of Hells Angels unhappy with how they’d been portrayed came and peppered his house with shotgun shells. At this point, most aspiring photographers would have considered reverting to shooting landscapes and butterflies – but not Yan Morvan.

Born in Paris in 1954, Morvan has spent the last four decades putting himself in danger’s path any time he spots a story that others have overlooked. He’s reported from over twenty war zones, taken multiple bullets, had a nervous breakdown, escaped a car bombing, been kidnapped by a notorious Paris serial killer and been sentenced to death – twice, during the Lebanese civil war in the 1980s.

After each of his many brushes with death have forced him to take a break, it’s only a matter of time before his restless nature gets the better of him and he’s back behind the viewfinder in another situation few others could stomach. After his run-in with the Hells Angels in the 1970s, Morvan continued to shoot rebellious youth, from rockers and skinheads to the street gangs of France’s deprived banlieues, where tower blocks and a lack of opportunities dominate the suburban landscape.

Red Warriors in suburbs, Paris, 1989

His career as a foreign correspondent began when he bribed a Turkish border guard to cover the 1980 military coup. He went on to report from numerous conflict zones, including the Iran-Iraq war, Northern Ireland, the Philippines, Uganda, Mozambique, Kurdistan, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Rwanda, Kosovo, Libya and Lebanon, where he won the Robert Capa prize and two World Press Photo prizes.

Morvan makes an effort to distance himself from conflict junkies. He’s revolted by war and his best work artfully reveals the futility and absurdity of violence. For now, he’s taking a break from conflict reporting to shoot a project on ancient and modern battlefield sites, but admits he’s eager to reveal another side to the conflict in Ukraine.

Morvan has regularly brushed shoulders with dangerous people in his exhaustive explorations of France’s underclass, but in 1995 he met Guy Georges, the ‘Beast of the Bastille’, who went on to be convicted of raping and murdering seven women between 1991 and 1997. Together with an accomplice, Georges threatened to rape Morvan’s wife and spray his kids with acid, then held him in an open-air kidnapping for two months while they forced him to take photos of themselves holding weapons to use to intimidate other local gangs. Morvan waited until the school holidays before fleeing with his wife and children to Nice. This narrow escape shook Morvan more than any of his other close calls because it was the first time his family had been put at risk. He took a two year break from photography, but of course, he would inevitably be lured back by another project and has continued to work with French gangs and cover foreign conflicts.

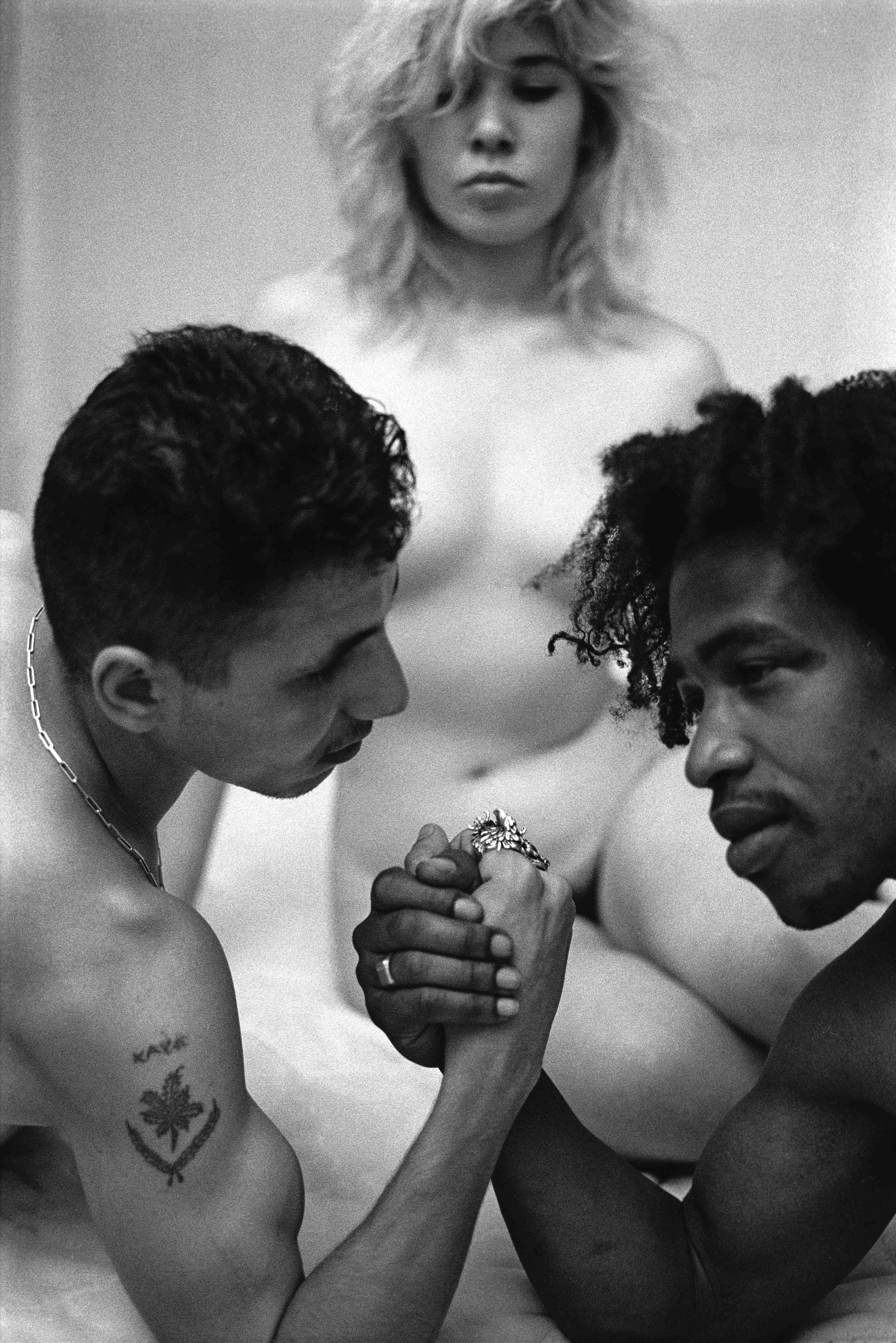

Gang members fight over girl, Paris, 1989

Why have you put yourself in harm’s way so many times to produce work?

Because I have no imagination, that’s why. I ask myself the same question, why do I do this? When I get back to Paris next week I’m involved in a story in Eastern France with a gang of gypsies who attack banks. I don’t know why I do it. Fifty per cent of my blood comes from Denmark and fifty per cent comes from England. I think they’re the worst people in the world, the English and the Danish. They’re war-like people, so it’s in my DNA, what can I say? I get bored the rest of the time. The Pax Romana is not good for me.

Does it take a certain disposition to work in dangerous environments, like war zones?

Maybe it’s because I’m a peaceful guy, you know. I don’t understand violence. I think stupid people use violence. When you can’t talk to people or you can’t explain something you resort to violence… It also takes thought control. Before I go to a hotspot I think a lot. I don’t take any risks and I always work alone. You have to feel your instincts. I always had a driver or I would be driving the car and I would say, ‘OK, stop there. I’m not going any further.’ Sometimes other people will want to go further and sometimes they never come back. You have to feel, and you have to learn to feel. You have to feel everything, like a general. Think all the time and never go too far. Sometimes you get a light which sparkles and says, ‘Take care’. But some people don’t. They don’t stop and they die. It’s like when you’ve been drinking: you have to say I’m drunk and I’m going to stop. It’s the same with war.

Bobby Sands hunger strike riots, Belfast, 1981

Do you remember the first time you thought you were going to die?

If you imagined that you would die, you would never do the job. Once I was captured in Lebanon and they killed the people close to me. A guy fell down screaming with a knife in his belly and the soldier came to me and I said, ‘My god, it’s my time.’ He didn’t do it because the chief said, ‘No, not him.’ The day after I was on the plane back home to Paris. I waited three months and then I returned.

What went wrong when you found yourself in trouble?

Every time I had trouble was my fault. I was going too far. I got excited, I said I’ve got to get it. I want to be the best. Arrogance and selfishness. It’s an awful thing to say but war business is like competition, you know? You have to be the best…. As I’m getting older I get afraid more often but when I was twenty it was like a game for me. There was something exciting happening every night with guys on motorbikes or whoever. Now I’m scared when I think about all the things I’ve seen. I think, ‘My god, what a crazy guy. I’ll never do this again.’ But that’s not true.

Revolutionary rap group Minister Amer, Paris, 1995

How do you cope mentally in conflict zones?

I become a robot. I compare myself to a surgeon and I’ve spent a lot of time with surgeons. What is a surgeon? They bring you a guy with no more guts and blood everywhere, and you don’t think, ‘Oh what a poor guy.’ You don’t think too much about the situation but you do what you can to help and your job is to repair. My job is to get the best picture, so I don’t care about anything else. I think about my aperture, about the best framing, and so on. Just like a surgeon… or a butcher, if you prefer. Surgeon for a good photographer, butcher for a bad photographer.

I remember in Beirut in 1992 there was a guy who picked up a machine gun and started dancing around with it. He got crazy, and he loved it. Afterwards he would say, ‘Oh my god, war is terrible’. But at the time he loved it – I saw. I’ve read a lot about post-traumatic stress disorder but I’ve never felt it. I’ve done a lot of stories on sex, gangs and war, but I can only do it for so long. I change between different things because it can make you crazy. People who chase war stories all the time are psychopaths. It’s crazy to see people die all the time. I’ve felt myself losing control and said to myself: stop it, before you start shaking. It’s a crazy job, you can die like that! You can be at home, quiet watching TV with a nice girl and the next day be somewhere terrible. It’s crazy, it’s like schizophrenia.

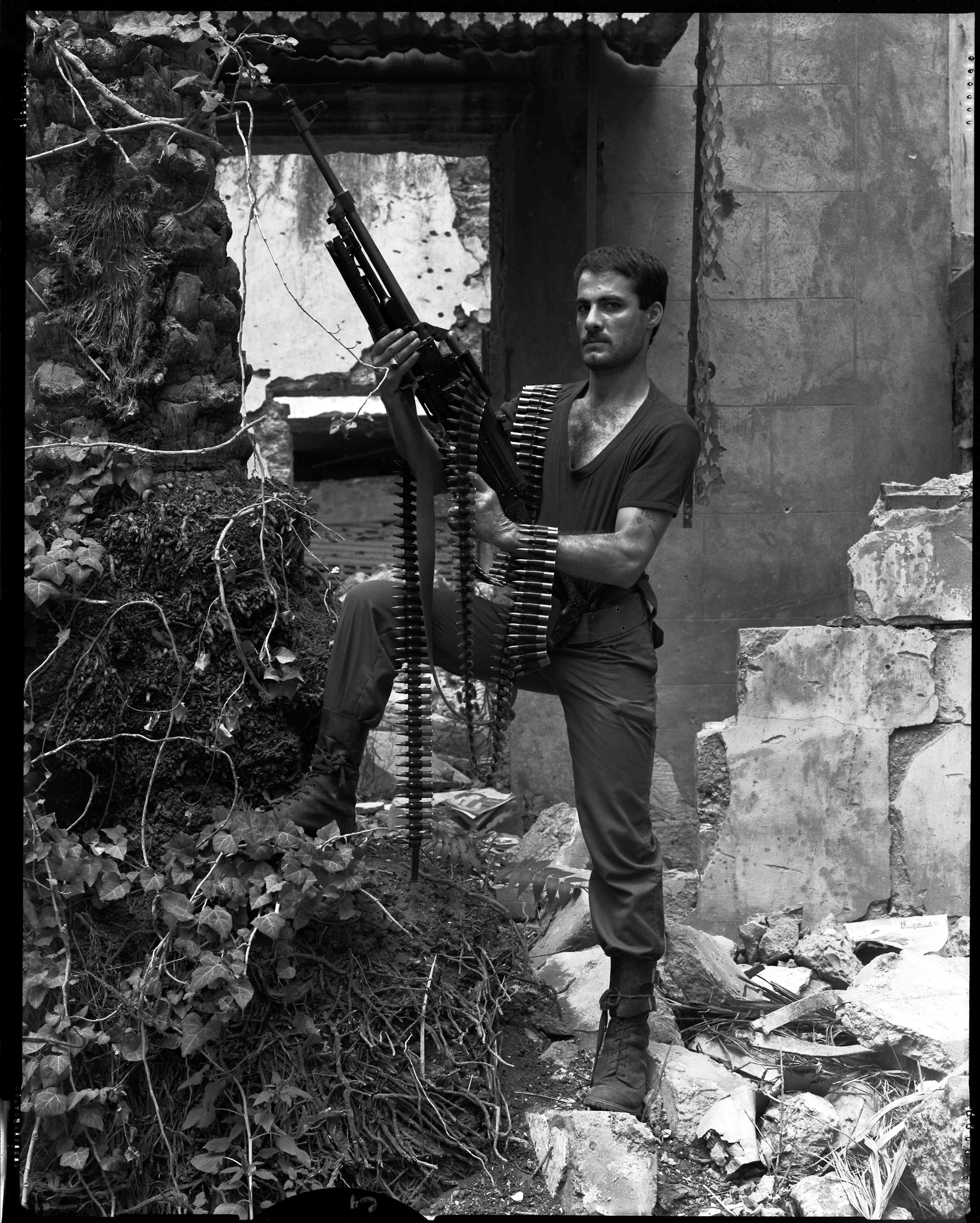

Shi’ite fighter on the Green Line, Beirut, 1985

When do you know when to say enough is enough?

You realise what you love, you know.

Did having a wife and a family change the way you work? Did that ever make you hold back?

I’m selfish, you know, I am a very bad guy. I don’t care… I have to do the job. If I don’t do it I die. When I stay at home for a week or two I feel weak. I’m not shooting wars now but I have to do something, I have to be making photographs. I love the battlefields project I’m working on. I’ve been to Beirut, Libya, Ukraine and Haiti. I’ve travelled all over the world to visit these ancient and modern battle sites. I went to Troy, I think about the Romans Legions fighting the Persians and all that, I love it. I’m involved in history and I’m reading a lot. If somebody told me to stay at home, I’d kill myself. It’s like air for me, it’s oxygen.

Bikers, Paris, 1977

What is it that always draws you back in?

I think about the pictures. I say, ‘I can do this.’ I always know what I’m going to do before I go. I’m reading books and magazines all the time and looking at other photographers’ work. If I can do something different or explain something that the others didn’t then I have to go. You have to prove yourself every time. If you don’t prove yourself, you don’t exist anymore. That’s not so easy. Your brain has to be working all the time, thinking about new stories, new politics, new history and new aesthetics. You have to mix all of that together and find something different to everybody else.

How did the Guy Georges kidnapping affect you?

I stopped taking photographs for two years. I had problems abroad and I didn’t care, but this time they were at my home. They picked me up every day and threatened to rape my wife and throw acid in my kids’ faces. I didn’t know Guy Georges was a serial killer but he was frightening. It was awful, the worst time in my life. If you die on the battlefield it’s not a big deal, you get a bullet: five minutes. But I felt what a cow or a pig feels before they go to the slaughter house. I couldn’t move, I really felt like an animal before being slaughtered. We are all animals.

How did the situation spiral out of control?

I thought I could play with them but violence is the king. If you have violence you rule the world.

Have you had any other close calls in the suburbs?

When I was working with the gangs in Grigny, I met Amedy Coulibaly, who killed the Jewish people at the kosher supermarket two days after the Charlie Hebdo attack. He told me he had a kalashnikov. Him and the people he associated with were all completely stupid, you know? Uneducated. The real problem in the world is a lack of education. People don’t learn languages, they don’t read books. And the government allows them to be like that because it’s easy. People are more and more stupid because they watch TV and they’re on their iPhones or whatever. In fifty years there will be a disaster, everybody will kill each other.

What effect do you hope your work will have?

When I released Gangs Story I had a lot of interest from around the world, but nobody in France wanted to hear about the problems I revealed in the suburbs – they didn’t want to see it. Lefties and righties are the same, they just want to make money off the back of poor people. My job is to show what’s happening. For twenty to thirty years I’ve been trying to show that something would happen with the gangs from Grigny and elsewhere, but nobody cared until they killed seventeen people. Taking photographs allows you to show what’s happening, the consequences of our actions. Photography today is shit. Everybody is selfish and nobody cares.