The Man Booker Prize winners you need to know

- Text by Alex Robert Ross

Last night the Man Booker panel announced László Krasznahorkai as the winner of its 2015 International Award. A Hungarian writer translated into English, Krasznahorkai was described by the panel as “a visionary writer of extraordinary intensity and vocal range” on the level of Kafka and Beckett. Nobody seems upset by the announcement.

Krasznahorkai’s award will likely remain uncontroversial. Prominent literary figures have been championing his work for years and those upset by the ‘international’ award going mostly to English-speaking North American writers will greet the recognition of a writer in translation warmly.

But, almost inevitably, such a prestigious award has drawn itself into a soap opera narrative more than once over the years. In response to both the international award and the main award for fiction, panellists have stormed off in protest, critics have thrown their arms up in despair because their idols have been overlooked and, more than once, accusations of racism and elitism have been levelled at the judges and sponsors.

And in amongst all that, some brilliant, progressive works from disruptive and radical authors have had the honour bestowed upon them. Here are Huck’s favourite winners. We’ve thrown some of the controversy in for good measure.

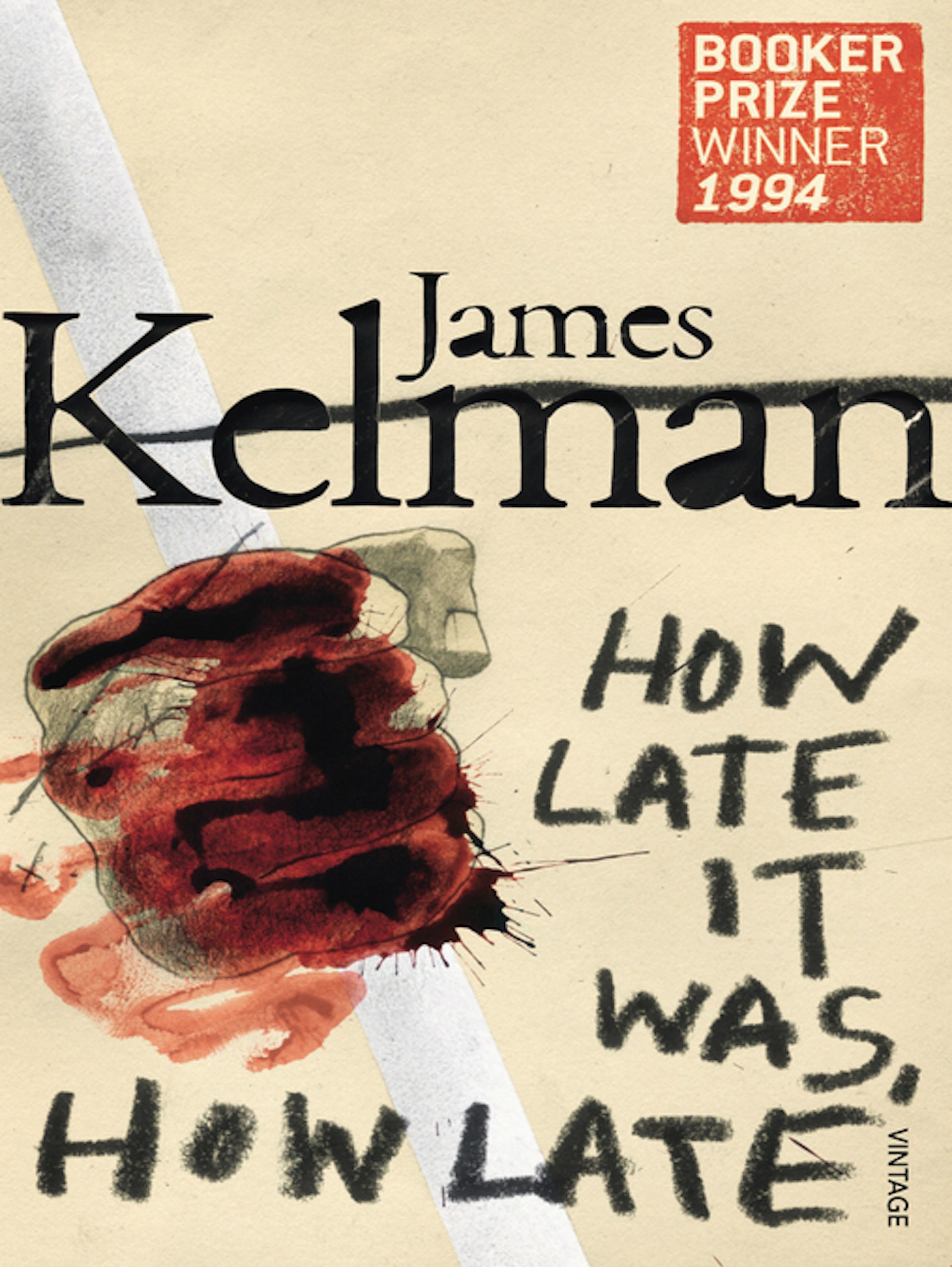

How Late It Was, How Late – James Kelman

When two judges threatened to walk off the Booker panel in 1993 if Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting made the shortlist, the now-classic novel was pulled to placate them. Written in a Scottish dialect and – perhaps most importantly – intimately concerned with society’s unseen, undoctored protagonists, the panel were accused of snobbery for their oversight. They couldn’t afford that level of short-sightedness two years running, though, and in 1994 James Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late took the award home. It’s dull to compare Welsh’s and Kelman’s work purely because they use the word ‘fuck’ a lot, but Kelman’s victory was supposed to be a sign that a novel based on a character who suffers at the hands of the established order, written in a language heard outside of Oxbridge, could be canonised.

G. – John Berger

John Berger’s experimental, idiosyncratic novel about a lust-driven libertine is now remembered more for its author’s rejection speech to the panel than it is for its content. Berger noted that the prize’s sponsors, Booker-McGonnall, had accrued a great deal of their wealth through trading in the Caribbean for 130 years or so. Like a badass, Berger called them out for it and then pledged half of his prize money to the British Black Panther Movement, “the black movement with the socialist and revolutionary perspective that I find myself most in agreement with in this country.” Just typing that out was enjoyable.

Vernon God Little – DBC Pierre

In 2003, mainstream American culture had shifted worryingly towards the disposable with the media favouring crass populism over insight. Reality shows ruled the airwaves and the youth that failed to fall in line with fear were feared themselves. In amongst this, Australian-born DBC Pierre’s Vernon God Little was a tragic portrait of Western society’s logical endpoint in which a young man attempts to navigate an uncaring ideology based almost wholly on spectacle. With a dark humour and a keen eye for the absurd, it remains one of the great critiques of its era.

The Remains Of The Day – Kazuo Ishiguro

In Huck #50 Kazuo Ishiguro told us that the time he spent volunteering in homeless hostels in his youth affected his writing deeply: “I always felt vaguely guilty that I learned so much that helped me in my fiction writing,” he said, “But I did learn quite a lot from that experience. It certainly helped me in the way I look at characters and to some extent the way I create the worlds in my novels.” The world that Ishiguro saw then was one of societal lines that couldn’t be crossed, in which systems of support and human relationships were based upon a pre-ordained social order. The Remains Of The Day, his third novel, has this concern at its heart as its protagonist muses on missed opportunities at love and life as a butler working for a wealthy, titled family. Ishiguro’s writing has always been based on empathy, an ability to pinpoint and draw out a character’s deepest hopes and regrets. In an era of self-interest, its recognition by the Booker panel is a testament to Ishiguro’s subtlety above all else.

The God Of Small Things – Arundhati Roy

Many in the British literary press wrote the 1997 Booker Prize off at the shortlist stage. Many of the white, male titans of literature had been left off the list and what remained was deemed scrappy at best. Arundhati Roy’s The God Of Small Things drew special criticism too because, after all, Salman Rushdie was Indian so India had basically been covered already. The God Of Small Things, in spite of that, was a sprawling, complex novel that changed voices and locations but never lost its focus, laying bare the injustices and torments of every territory it drops into.

Alice Munro

A little ahead of the curve, the Man Booker panel awarded its International Award to Canadian short fiction writer Alice Munro in 2009, four years before her fully-deserved Nobel Prize for Literature. Bound up in contradiction, experiencing the thrills of joy and madness simultaneously, Munro’s characters are almost shocking in their reality, painfully honest, and never anything less than thrillingly complex. She will unquestionably be remembered as one of the great short story writers of her age, leaving both the public and the panel in a rare moment of mutual congratulation.