Why punk keeps connecting people across space and time

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Angela Boatwright, GODLIS

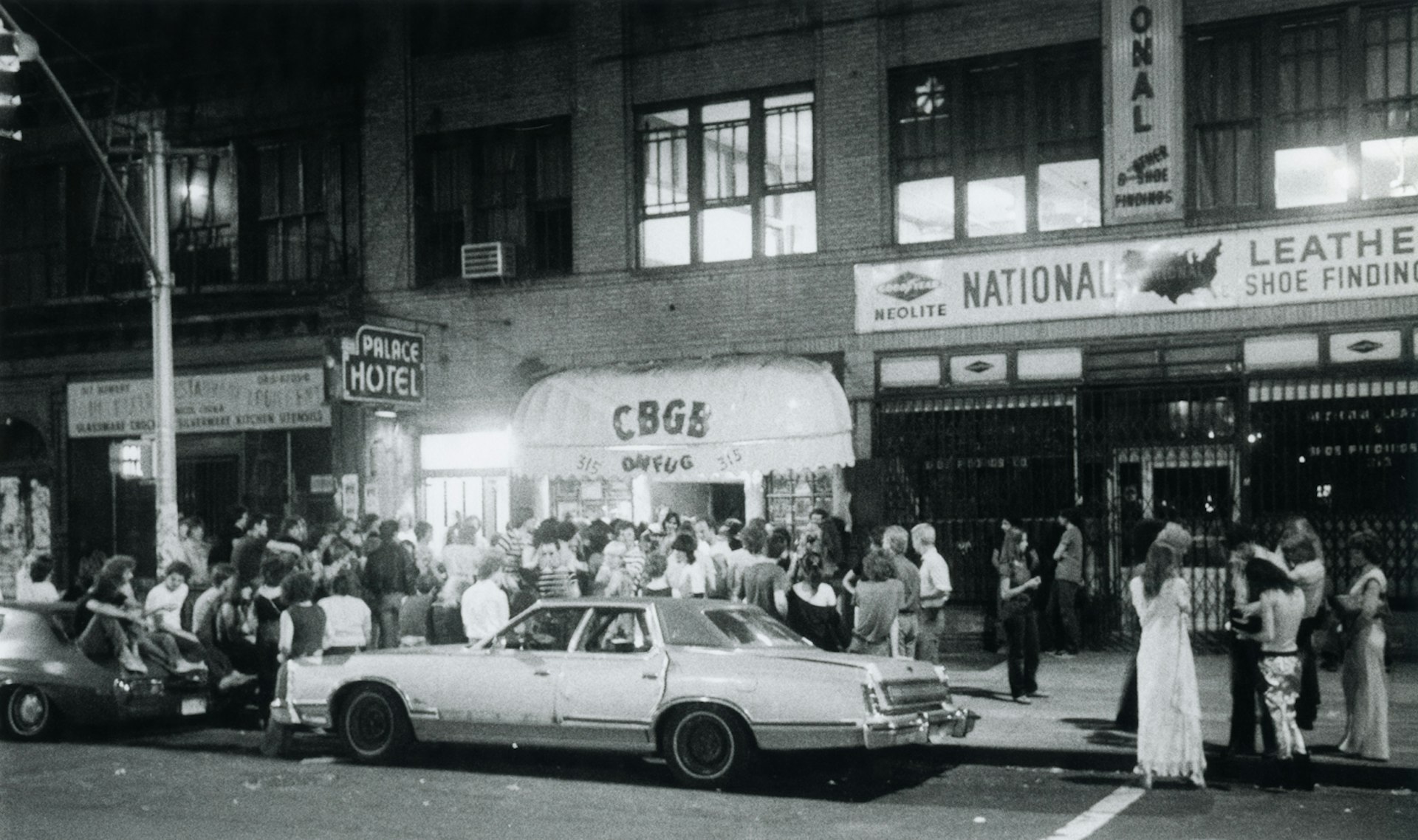

On a cool night late in the summer of 1976, David Godlis stood on the Bowery: a desolate NYC strip synonymous with flophouses and winos who’d lived under the shadow of the Third Avenue El train for more than a century. Although the train had been dismantled, that thoroughfare remained barren and bleak – but for a white awning emblazoned with black letters that announced “CBGB”.

At 25, Godlis had returned to his native New York towards the end of 1975 after spending seven years in Boston, where he studied photography alongside Nan Goldin and Stanley Greene at Imageworks.

Back in town, he’d pick up the latest issue of The Village Voice and flip to the classified section where he perused the help-wanted listings. It was there that an ad for a bar repeatedly caught his eye. Intrigued, Godlis set out to catch a band called Television. When he arrived, the streets were completely empty. He spotted the white awning and said to himself, “That’s got to be the joint.”

He opened the door and stepped inside what felt like a new world: a long, narrow room illuminated by neon beer signs hanging on the wall. At the front desk sat Roberta Bayley, who had shot the cover of the Ramones’ first album, though Godlis didn’t know who she was at the time.

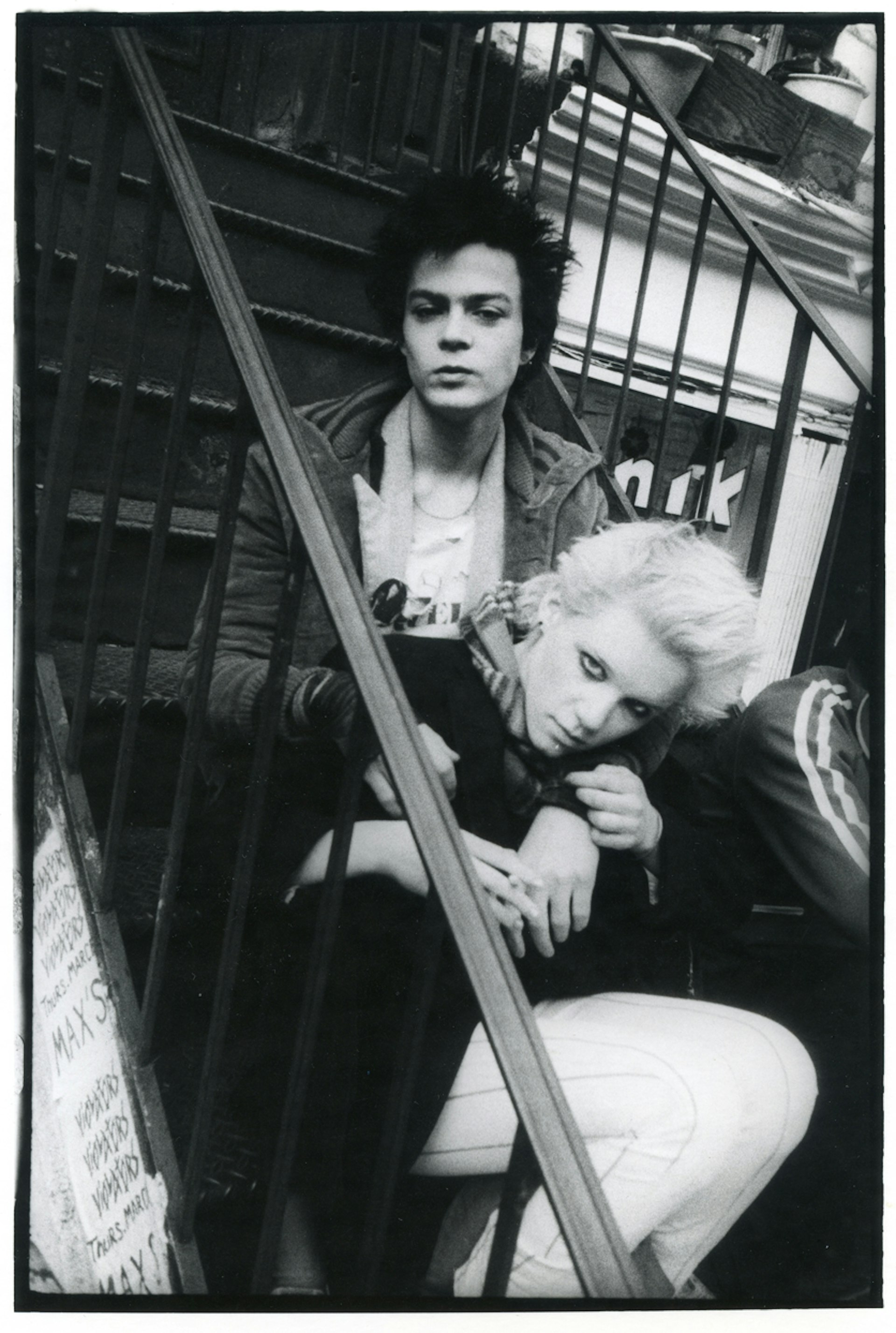

Punk Couple on Steps, St. Mark’s Place, 1981. Photo by GODLIS.

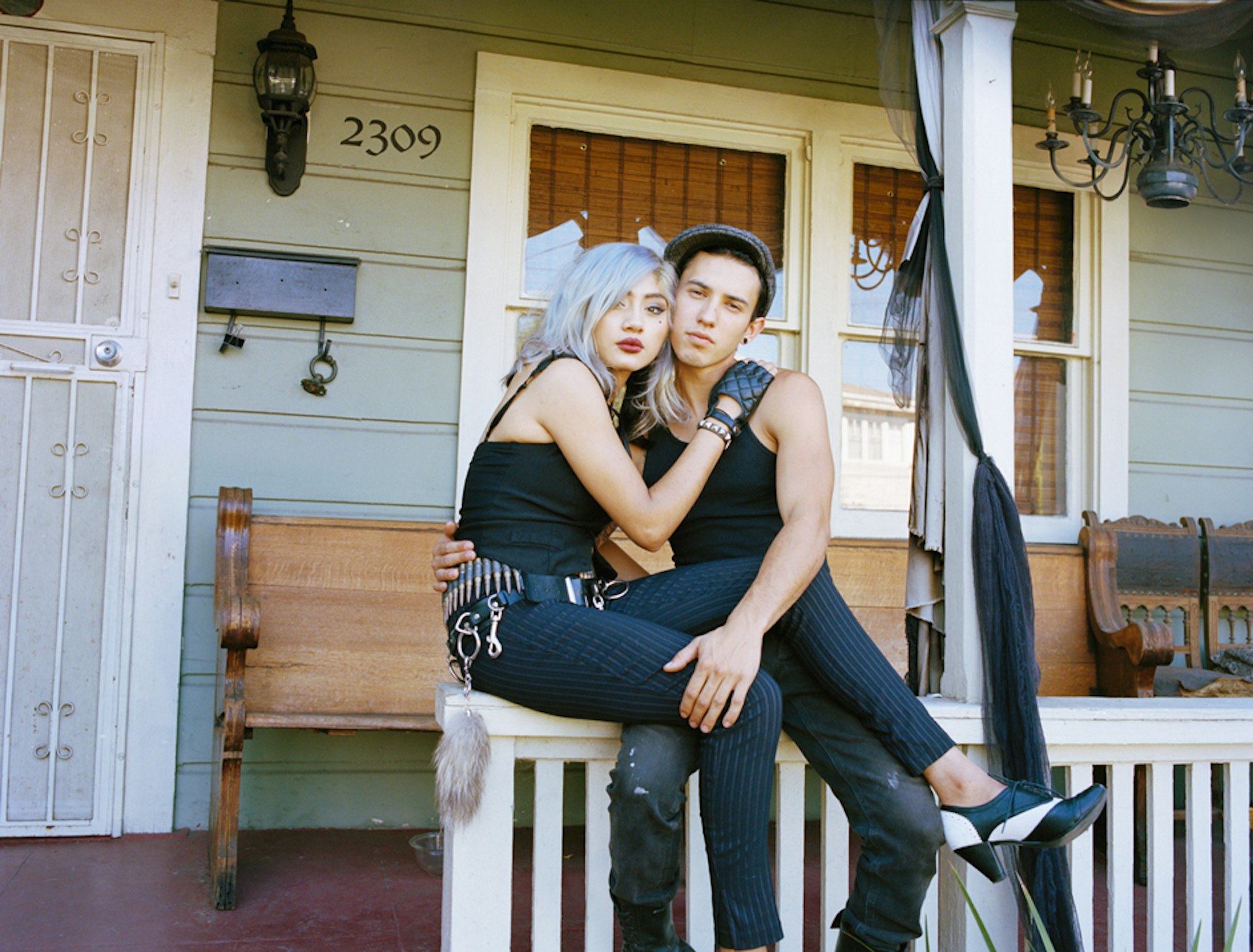

Luna and Tommy Lincoln Heights, Los Angeles. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

Inside, a couple of kids played pinball while others perched on benches opposite the bar. A jukebox lay silent as the sounds of Television filled the room. Godlis headed to the rear to check out the set, where frontman Richard Hell – backed by Tom Verlaine, Richard Lloyd and Billy Ficca – was hovering over the mic.

“There weren’t that many people there,” he says. “But I remember thinking, ‘Everyone here probably has a Velvet Underground album.’ You could feel something was going on. It was enough to make me go, ‘I am coming back.’”

From that day on, Godlis was at CBGB almost every night. Stuffing as many rolls of film as he could fit into a skinny pair of jeans, he shot on a Leica without a flash, using the techniques of Brassaï to document bands like the Ramones, Talking Heads, Blondie, the Dead Boys and Patti Smith.

Inspired by the work of Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand, Godlis began to compose a body of work that captured New York punk in its formative years. He picked up gigs with NME, Sounds, Rock Scene, and New York Rocker, then began publishing images using his surname as a moniker.

Soon the scene he had stumbled upon became his own. “The thing about being a photographer is that you are in the moment,” he says. “You’re out and you’re shooting and you lose yourself in that. You become a combination of your real self, your unconscious self, and the things and people that are in front of you – and you go to that other place with them.”

Joey Ramone, 1981. Photo by GODLIS.

Cerebron were the only band who played before a show was raided in Watts, Los Angeles. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

But by 1979, Godlis was done. Though he continued to photograph at CBGB over the years, he closed a door on that body of work. “I remember thinking it was played out around the time I saw John Cale and Nico play CBGB in ’79,” he says. “The bands began to play other venues like the Mudd Club and travel out of state.”

By then punk had already made its way across the continent, landing on the West Coast with a bang.

Los Angeles, 2013. Angela Boatwright, who grew up in Columbus, Ohio and lived in New York City for 19 years, found herself at a backyard punk show in City Terrace, East LA. Dusk was settling in a veil of smog and the opening band was setting up.

Like Godlis, Boatwright has never forgotten her first encounter with a brand new scene. “I saw young people playing drums while sitting on lawn chairs, their drums duct-taped together. They were playing music for each other, making T-shirts and patches for their own bands and selling them to one another. There were 200 kids there and that wasn’t even a big turnout. Other than myself, there were no outsiders.”

Rey taking photos near El Pino, Boyle Heights. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

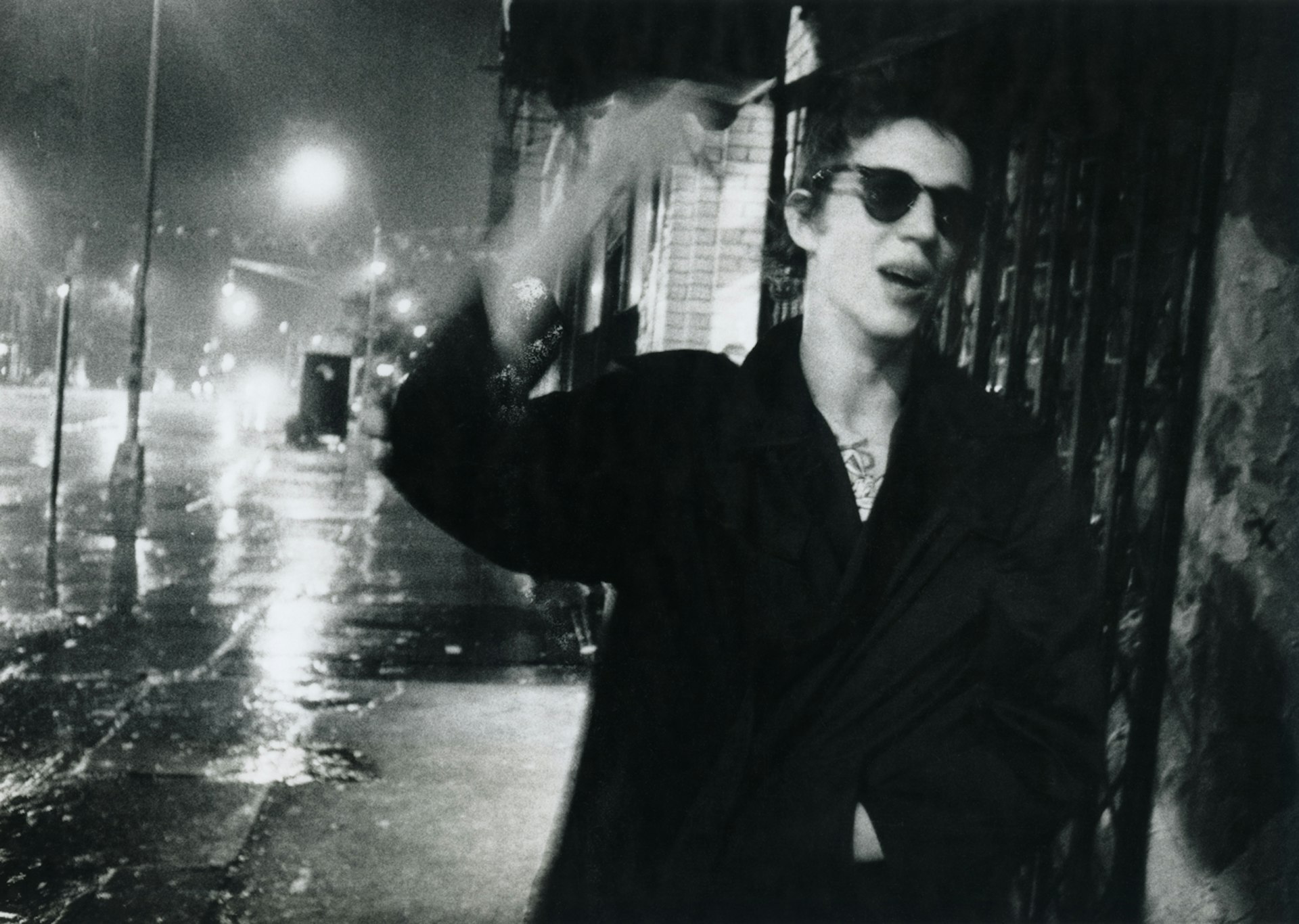

RIchard Hell, Bowery Rainstorm, 1977. Photo by GODLIS.

Boatwright got her start as a photographer in 1990 when she was 15; within a year, she was photographing Kurt Cobain. She spent her days studying at New York’s Fashion Institute of College and her nights in the mosh pit at CBGB, capturing the hardcore scene on film. After moving to LA in 2011, she hooked up with old friend Ron Martinez, who invited her out to the Valley to see him play in legendary street-punk band Lower Class Brats.

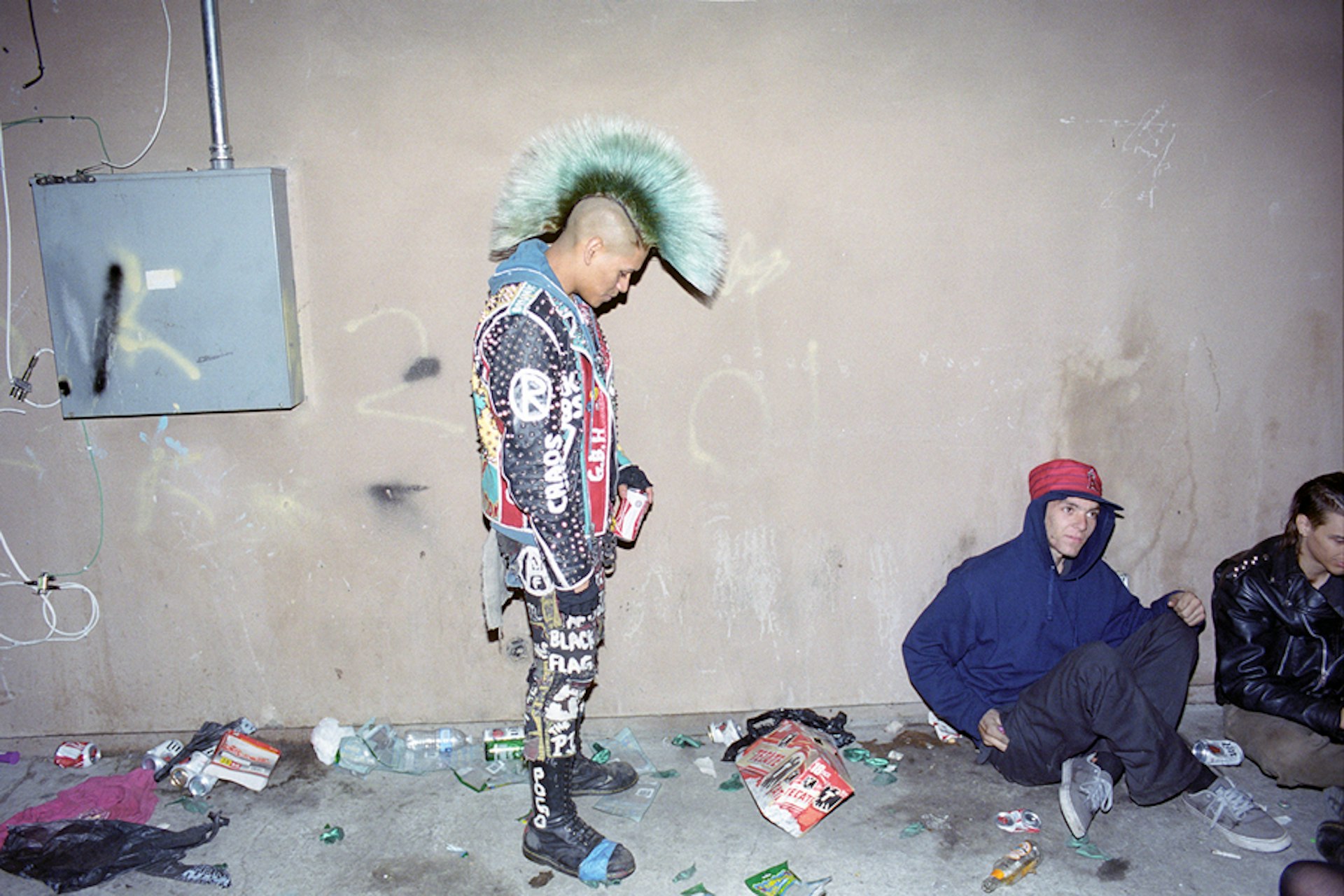

Boatwright immediately felt at home. She started looking into what was happening in East LA, where punk was developing its own fierce aesthetic among the Latinx community. Here, punk evolved to meet the needs of kids who needed an outlet for their alienation and creativity – a culture with no rules that allowed them to be whoever they wanted to be.

But it wasn’t an easy scene to find. Though punk arrived on the West Coast in 1977-78, in East LA it remained underground and undocumented for decades. “You can’t find the music easily,” says Boatwright. “You have to dig deep to find it.”

The photographer did just that in order to make her 2016 documentary film Los Punks, which captures the raw, visceral energy of the street punk scene in Boyle Heights, South Central, and Watts – an underground world that unfolds in backyards and abandoned houses. “In Latinx culture, you will have quinceañeras and family parties at your house – so why not a punk show?” she says. “The shows give them a chance to gather and be themselves without rules. There are no parents, officials, or security telling them not to stage dive.”

Punks at Indiana Street show, Boyle Heights, July 2015. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

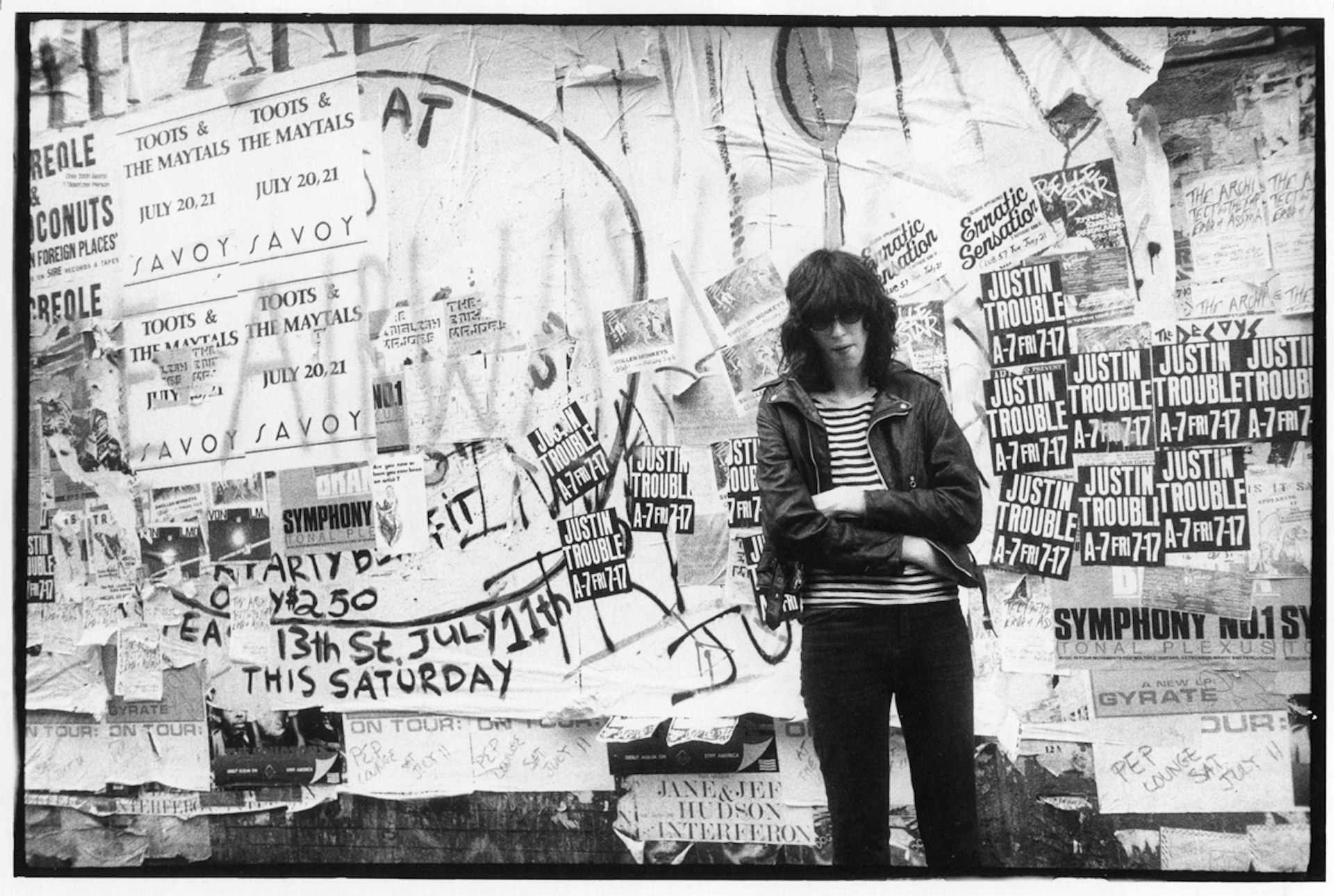

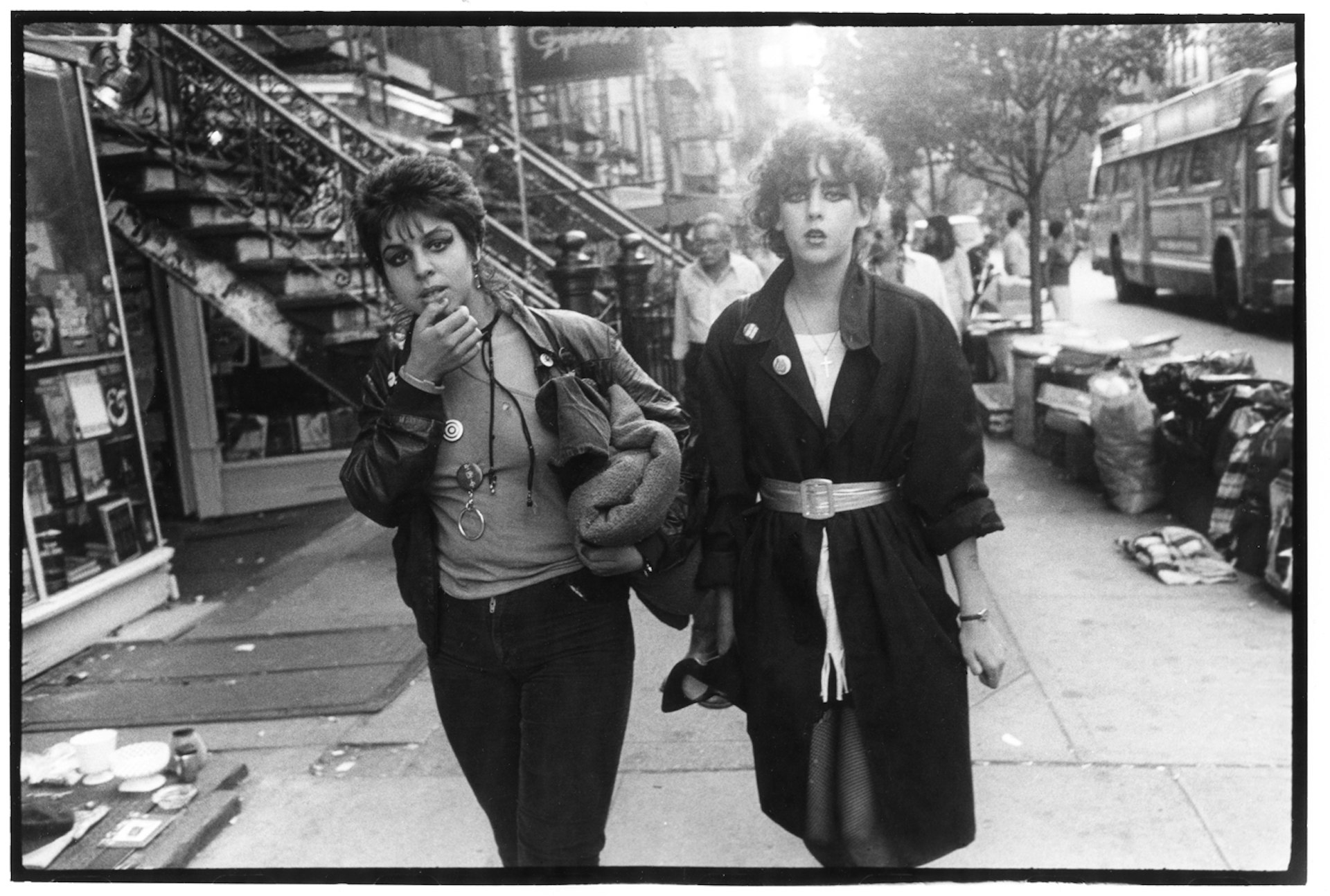

Punk Girls, St Mark’s Place, 1980. Photo by GODLIS

Despite the differences in time, place, demographics and music styles, early New York punk and its contemporary offshoot in LA have both benefited from relative isolation. Without the glare of the media and demands of the record industry, both scenes became an integral part of the underground, with bands, fans, promoters and managers dictating the sound and style.

In New York, punk was the next natural chapter of the counterculture’s ongoing story. “A lot of punks came out of the hippies, which were already anti-mainstream,” says Godlis. “The record companies were trying to shape what people listened to and we were like, ‘No!’ We were 25 or so and we were starting to see 30 [years] ahead. Bands like Television and the Ramones were like, ‘Fuck this!’”

Although the Sex Pistols would become synonymous with anarchy and implosion, the New York bands were in it for the long haul. The Ramones, who came up with the idea of four brothers in leather jackets, would go on to play more than 2,000 shows over 20 years, while artists like Debbie Harry and Patti Smith are still performing in their 70s. “They were three-chord wonders,” says Godlis.

“Everyone was coming of age at the same time,” says the 66-year-old, looking back. “Most of us were alive when Elvis Presley first started in 1956. We were impassioned with these influences and looking for a way to get it out. The scene bred self-confidence for people who had low self-esteem, who walked into that room with a lot of swagger. We all felt good about ourselves when we walked out at four in the morning.”

CBGB became a home for rebels, precisely because owner Hilly Kristal didn’t have any rules. “There was no place that ran a club like it,” he says. “There were enough creative people who were like, ‘You have a great spot. Let us tell you how to do this,’ and Hilly was hands-off enough to let things happen.”

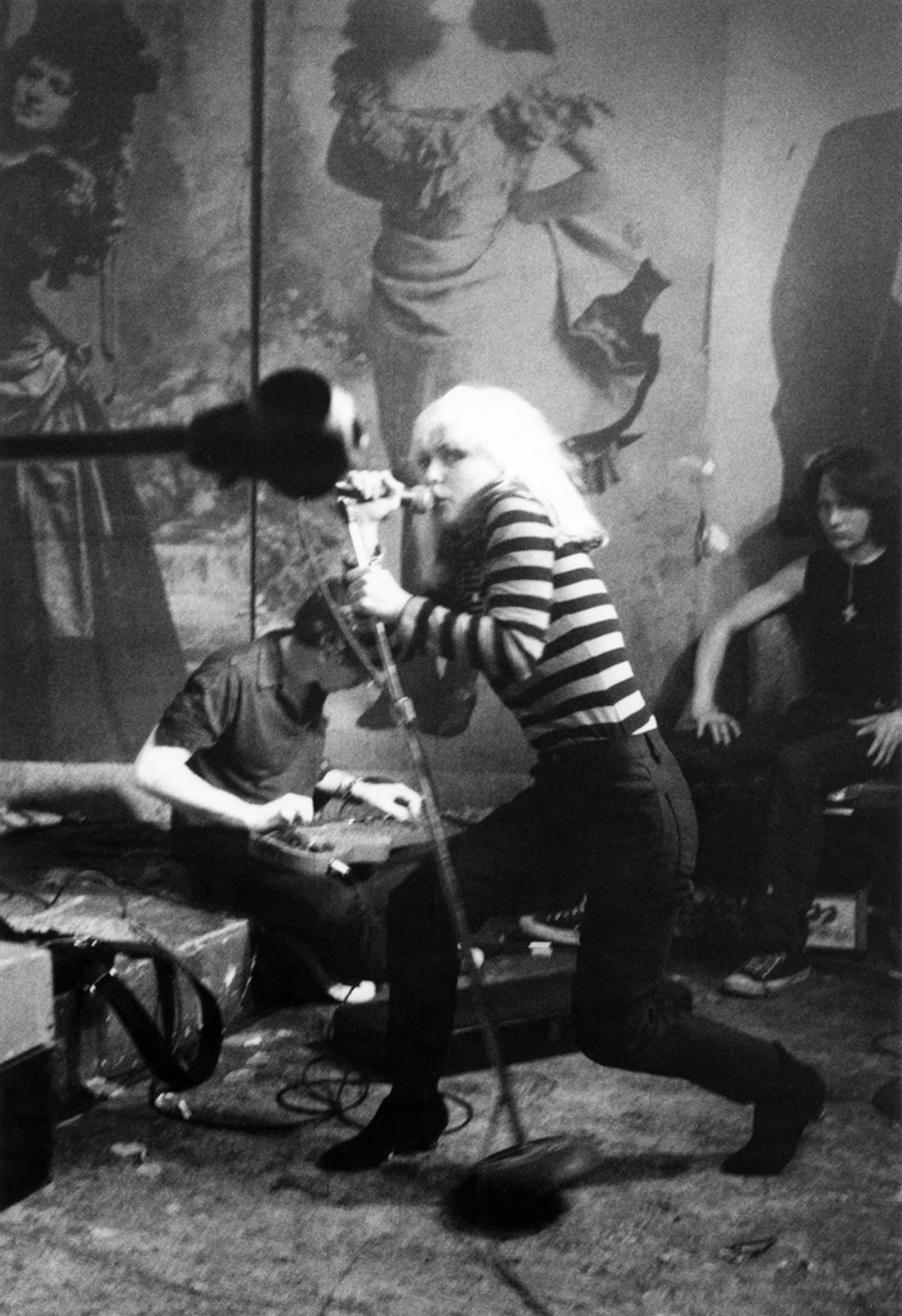

Blondie, CBGB, 1977.

The Casualties play a house show in East Los Angeles. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

That renegade spirit has persisted, with teens the world over still forging their own spaces in the name of punk. The benefit of being below the radar, says Boatwright, means LA punks dictate what they will and will not tolerate. “The tricky thing about punk is that there are supposed to be no rules; no one has officially defined it,” she says. “They are literally redefining what is acceptable in their scene minute by minute. It’s constantly evolving.”

This shape-shifting is mirrored in the spaces where the Latinx punk scene takes place. Unlike their counterparts in more privileged parts of the city, “there are very few all-ages venues so young people are forced to throw their own shows in alleys, driveways, backyards and abandoned houses,” says Boatwright. “To wind up at a show and see all this ‘fuck you!’ energy is incredible.”

The “fuck you!” that emanates from these urban backyards is more than just adolescent rage: it’s a symptom of an unforgiving landscape. “LA has a vicious history with racism,” says Boatwright. “It’s such a segregated city – a place where freeways were built to corral different communities. My punks are dealing with more than artistic freedom. You have kids that are dealing with DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] right now. I see a lot of anger. These teens are fighting to understand, for their identity and who they are. They might be fighting against having a dysfunctional family or against the bullshit societal rules that keep them down for generations.”

Boatwright has witnessed violence erupt at shows, but is quick to set this within a broader context: constant police raids, racial profiling and high rates of youth unemployment. At the same time, there are punks who transform their frustration into a force for good. “Protest and rebellion requires organisation,” says Boatwright, referencing a woman named Erika who founded South Central Vegans to encourage people to eat healthy and keep money in their communities. “Some are moving forward.”

Ivy and Lance Downtown Los Angeles. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

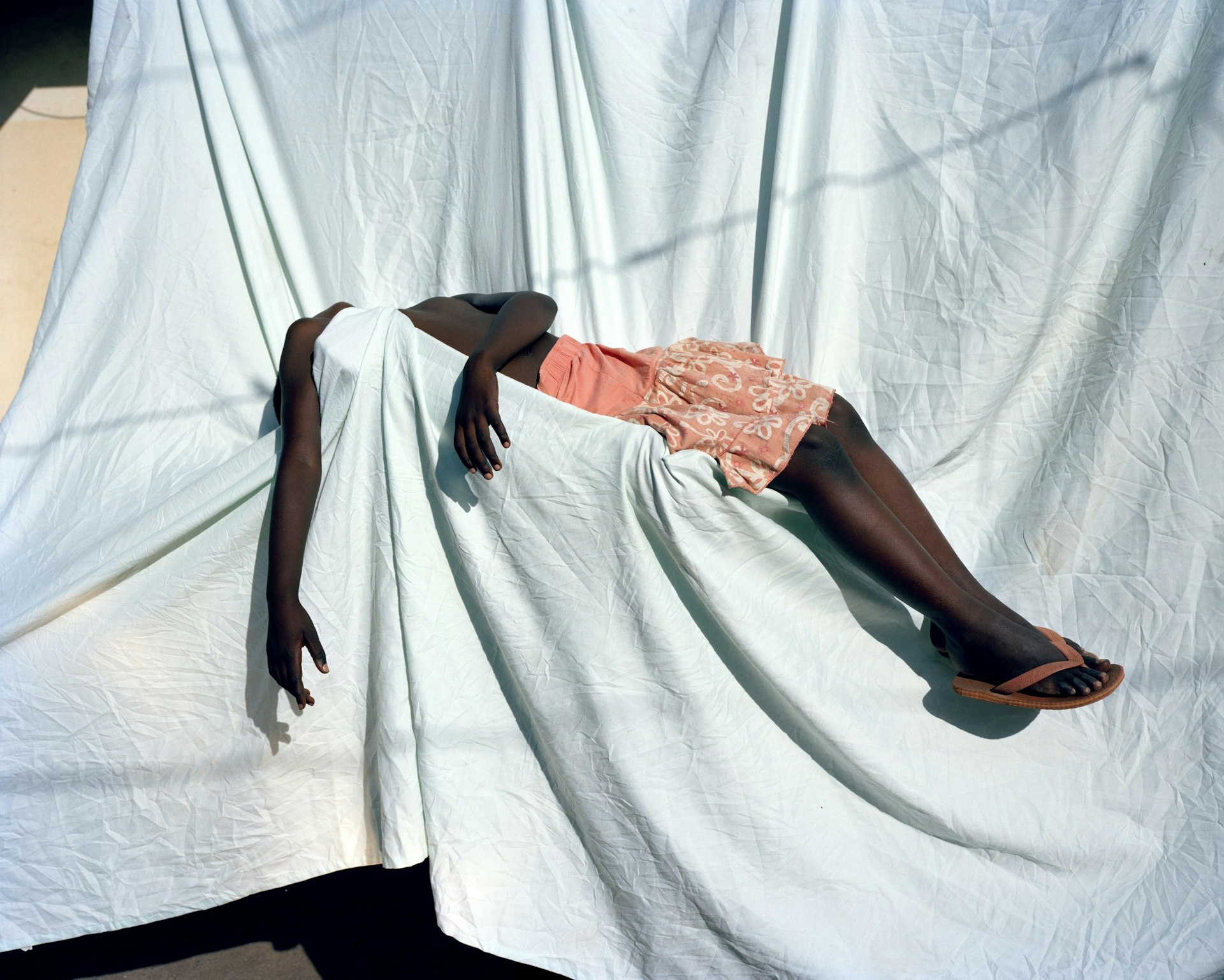

Photo by Angela Boatwright.

For the street punks, the mosh pit becomes a space for catharsis and release. Boatwright understands this better than most. As a photographer, she’s documented the punk, hardcore and metal scenes, and is currently working on a new documentary about Juggalos.

“I can relate to this music, the aggression, to getting into a mosh pit and fighting or punching someone,” she says. “If you come from a dysfunctional family, you are a fighter your whole life. I know this first-hand: I might be white, 42 and from Ohio, but I grew up in a horribly dysfunctional family so every breath I take is a fight… As a teenager you are in a second infancy and you are trying to understand things, so life becomes a fight.”

In Godlis’s New York, violence at shows didn’t begin until the Sex Pistols came on the scene, when the fans started gobbing and spitting at the performers. Prior to that, CBGB was an ever-evolving space for musicians, artists, filmmakers and designers who were reinventing themselves night to night. And yet still, it was no utopia.

By the time Sid Vicious was arrested for the murder of Nancy Spungen at the Hotel Chelsea in 1979, the scene had begun to transform into something else. “The younger kids were saying, ‘Enough with these bands. We are going to play less chords,’” Godlis recalls. “It started with Lydia Lunch, Teenage Jesus, Arto Lindsay, and would lead into Sonic Youth. Terry Ork, Television’s first manager, called it ‘No Wave’ and it stuck. The ’80s were starting to get into full swing – and not too far off was MTV.”

GBGB, 1977. Photo by GODLIS.

East L.A. Liquor, N. Fickett Street, Boyle Heights. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

Although video killed the radio star, video also ate itself. Boatwright notes that the West Coast street punks are the post-MTV generation, who don’t consume culture in the same way. The bands are not getting record contracts or putting out CDs. “You have to go to their Facebook pages, or a couple of bands will have someone create a professional video for them,” she says. “The music is not tangible at all.”

The freedom of the street punk scene, adds Boatwright, is both its saviour and its Achilles heel. Alongside violence and police raids, a much larger threat looms on the horizon. “The nomadic element in the scene allows it to exist but also threatens it,” says Boatwright. She recalls being at a show in South Central LA, watching the bands load into an abandoned house.

“I was waiting for it to get going and then the homeowners showed up with U-Haul trucks! Apparently the house had been sold and the new owners arrived at that moment. The promoter was very professional and said, ‘No worries, we’ll leave. Go ahead and move in.’”

Eric, South Central Los Angeles. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

The Casualties play a backyard show, South Central Los Angeles, July 2015. Photo by Angela Boatwright.

Gentrification is the scourge of modern life, decimating local neighbourhoods built by families over generations, erasing history and whitewashing culture. In Latinx areas across LA, the story is no different. “In 2013, I went to a show at the Euclid House in Boyle Heights, with 500-plus young people and the most incredible view of the LA skyline,” says Boatwright. “Fast forward to 2016 and by happenstance I caught this same house for sale for $600,000. I keep thinking the new owners will never know about the punk shows that were thrown in their home.”

And yet, as Godlis knows too well, nothing lasts forever. Having lived through punk’s blossoming youth, he also knows how influential a scene like that can be – especially if you stumble upon it at just the right time. “Stepping into CBGB was stepping into my future,” he says. “I was looking for something different and punk was that thing for me. A band would walk into the club with their guitars; I walked in with my camera feeling like, ‘This is my equipment and I am going to play tonight.’

“There is something that is entangled in photography, in the sound of the music, and the newness of being young in the world,” he says. “It’s very singular and yet you go through that experience together in a group – which amplifies and magnifies it. That stays in your brain. I like that it’s not graspable, because it if was, it could be packaged and it wouldn’t be that great.”

This article appears in Huck 65 – The Coming of Age Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.