Scenes from the frontlines of America’s never-ending war

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Peter van Agtmael

Coming of age in America, Peter Van Agtmael remembers feeling marginalised by a culture that elevated appearance and athleticism above all things. Searching for his own identity, he began dreaming of joining the military.

Van Agtmael would eventually go to war as a conflict photographer. In 2006, he began documenting the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, later chronicled in the books Disco Night Sept 11 (Red Hook Editions) and Sorry for the War (Mass Books).

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine dominates media coverage, Van Agtmael reflects on the lessons he learned as a photographer on the frontlines of America’s longest foreign war. “There’s a certain amount of groupthink, especially during wartime, that’s extends across all segments of the media,” he says. “It extends to photography as a desire for the most dramatic and brutal but somehow tasteful images that represent the human cost of war, as well as its melodrama. The pictures start to look the same.”

The Hungarian border closed at midnight to prevent thousands of Syrian and Afghan refugees from entering. Horgos. Serbia, 2015.

Preferring to ask questions, Van Agtmael adopts an ambiguous approach, allowing his photographs to open conversations, rather than provide reductive talking points, stale clichés, or stereotypes. His photographs explore the nature of conflict and the toll it takes physically, psychologically, as well as the way it manifests through both American foreign and domestic policy.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Van Agtmael reflects on bearing witness to horrific acts of war, and the disconnect between the rhetoric surrounding them in both politics and the media. “It’s a reminder of how unreflective the mainstream media can be about the historical context around these conflicts and the broader policy issues that potentially make them avoidable,” Van Agtmael says.

Adnan Thanon Younis, 53 years old, was blinded by an exploding shell in Mosul, Afghanistan. Photographed in Erbil, Iraq, 2017.

Soldiers raid a hamlet on the outskirts of Mosul after midnight on a winter weekend. Iraq, 2015

“As the conflict goes on and the media starts to lose interest in covering it, there won’t be much of an opportunity to uncover the layers and give this the depth and breadth it deserves,” he says. “I know how fickle and fleeting attention is, and that has a massive impact on the quality of the work that gets produced.”

Seeing the contradiction between the image of Western progressive liberal society and the romanticism and fetishisation of war, Van Agtmael recognises hypocrisy in the discourse. “It leads me to ask, what are these values if we can turn on a dime? I saw the same thing with the anti-racist stance people were taking in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd as well as the questions of gender quality following the Me Too movement,” he says.

“It’s like there’s this performative representation of values on social media, and now we are seeing it as it relates to the military because it’s the fashionable thing to do. I’m steadfastly refusing to post anything even though I have something to say because, like Bob Dylan said, I want to know my song well before I start singing.”

Ku Klux Klan, Tennessee, 2015

The Hungarian border closed at midnight to prevent thousands of Syrian and Afghan refugees from entering. Horgos. Serbia, 2015.

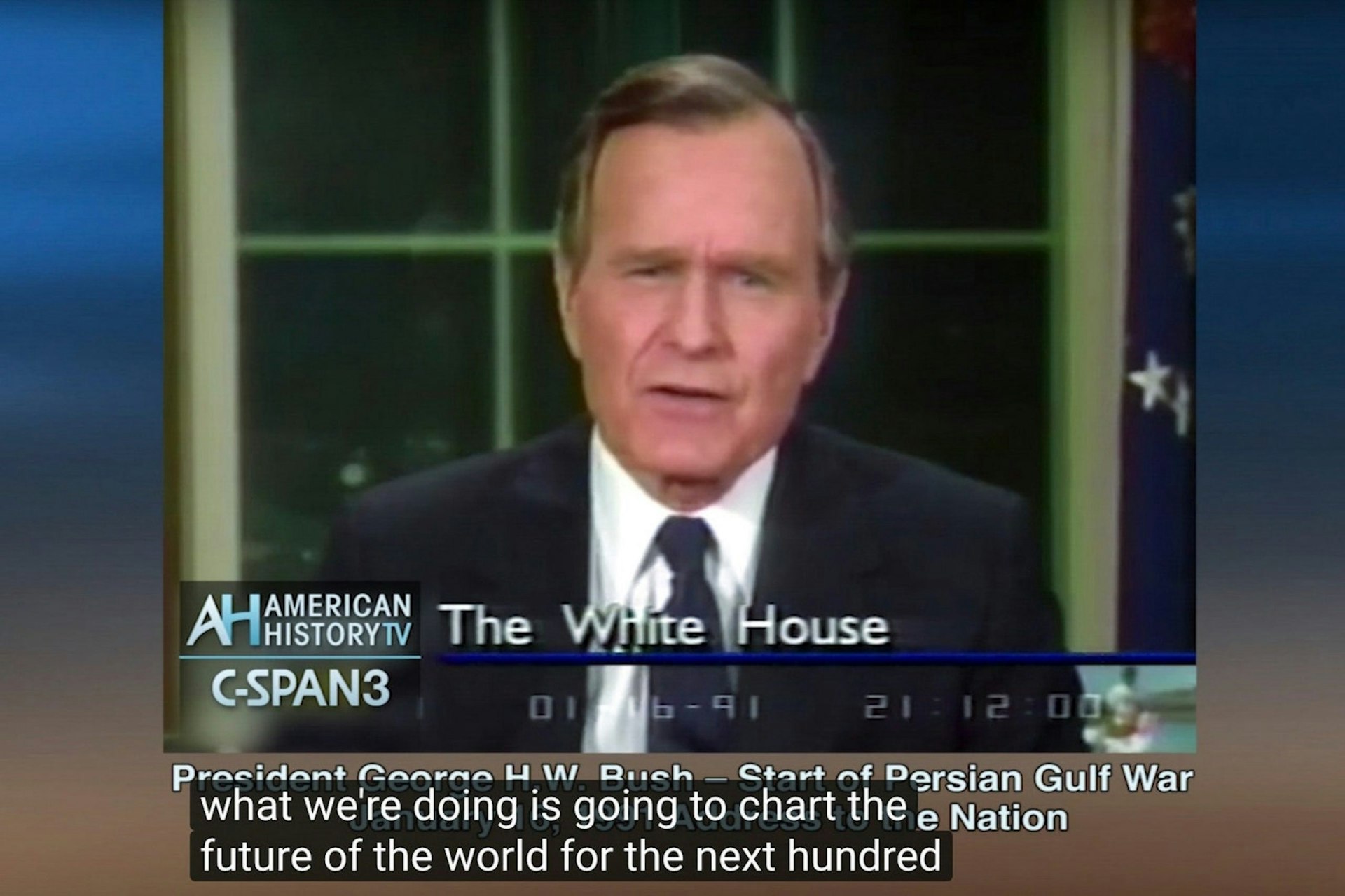

George H. W. Bush announces the launch of Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.