Stuck between two evils: rethinking the Syria conflict

- Text by Fiorella Lecoutteux

- Photography by Syrian Freedom on Flickr

“When you are detained, the jailers can do anything to you. They touch your body. They threaten you – once, they threatened to rape my five-year old son.” Farah Al pauses and points to graphics on her powerpoint. “Here are different ways they can torture you: the welcome (shabet) where they hang you upside down, the tyre (dubbab)… They also put electric rings on my fingers. I still have scars on my hands, legs and feet.”

Farah Al was one of two Syrian refugees who spoke out against Bashar al-Assad’s regime in the House of Commons last week as guests of the Rethink Rebuild Society. Two years before Farah arrived at parliament, MPs voted against military intervention in Syria, in August 2013. In that time, the west’s position on the conflict has shifted dramatically, but there is still no resolution in sight. Parliament’s vote in 2013 followed evidence that Assad had used chemical weapons against his own people. But as the threat from ISIS grows, and attacks on tourists in Tunisia and suspected involvement in the Russian jet crash in the Sinai last week show the extremist group is now able to project its power around the world, western governments and media have begun to see Assad as the lesser of two evils.

However, Farah was just one of a number of voices at recent events around London whose testimony revealed that the west urgently needs to rethink its stance towards Assad’s regime – which is responsible for the majority of civilian casualties. Western governments need to completely go back to the drawing board if they hope to end what UN special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura declared in January is the biggest humanitarian crisis since the Second World War.

Farah remembers the smell of weed and alcohol reeking from the jailer who tortured her. She was stopped at the Lebanese frontier in 2014 when she tried to renew her British passport, arrested, and spent the next thirty-six days in one of Assad’s detainment camps. “One day, as he took off my blindfold, I asked him: how can a person like you hit and torture us? He got quite angry at first, then he opened a drawer and pointed to some white pills.” The violence, she stressed, is a policy from above.

What began as peaceful, Arab Spring-inspired protests against President Assad in 2011 has since become the bloodiest civil war in decades. The Assad regime is estimated to have killed 200,000 Syrians, while ISIS terrorises the country from the north. Other opposition groups are made up of the Free Syrian Army, moderate Islamic forces and other jihadi groups. The Assad regime considers anyone who opposes it a terrorist.

After Farah finished speaking, a second Syrian refugee, Yasser Aljassem played a video filmed on his iPhone. A barrel bomb falls and explodes in the middle of a busy market square in broad daylight. Two children are stuck underneath the rubble. They are unable to breathe and their backs are fractured. Recruited by the Syrian army in 2010, Yasser defected a year later when he witnessed the violence perpetrated by his officers on peaceful protesters. Soon after his escape, ISIS killed his brother. Yasser says his experience illustrates that Syrian civilians are stuck between two evils – and there is no easy way out.

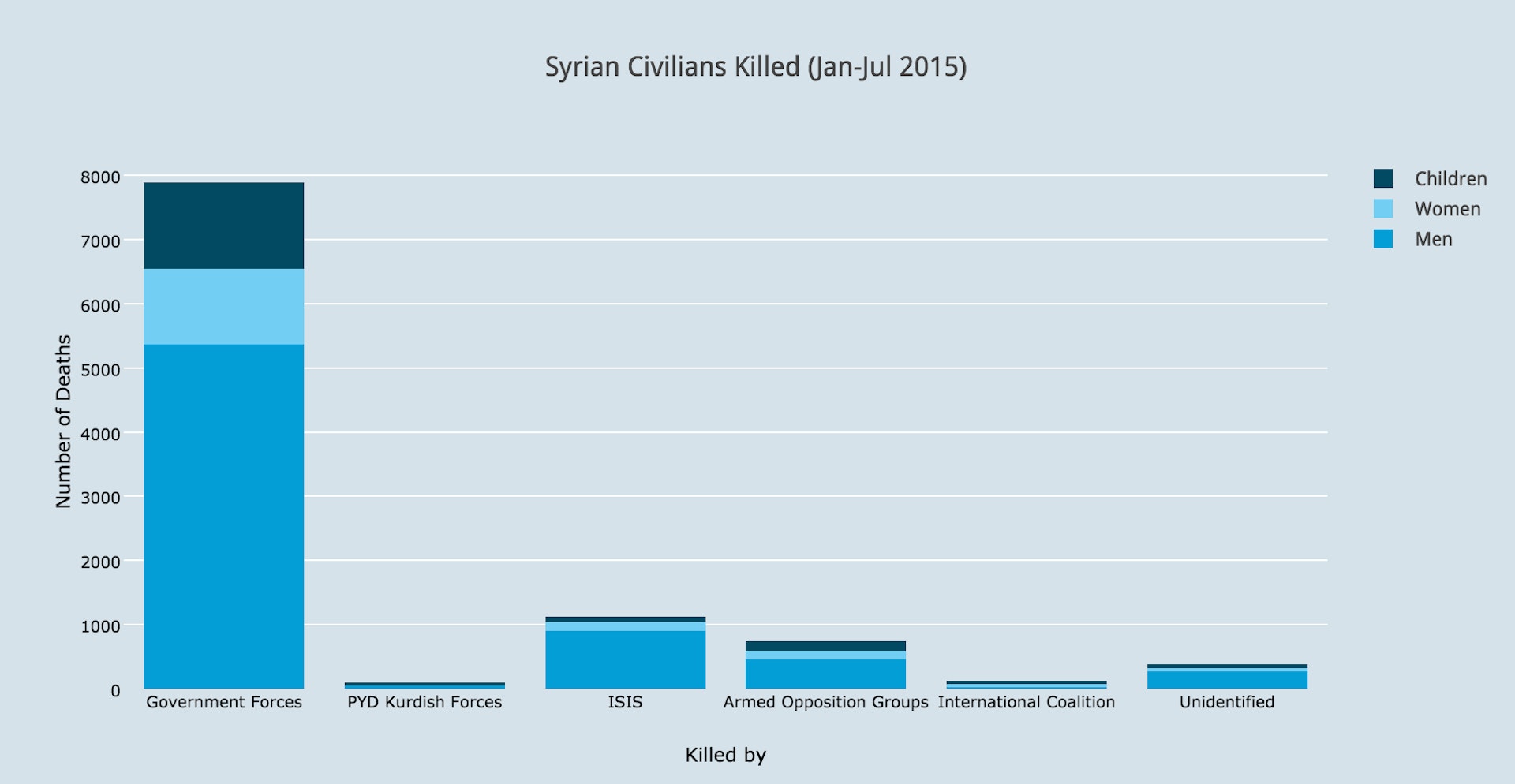

Yet it is Assad’s forces who continue to spread destruction through daily and indiscriminate air strikes on civilian areas. Despite Assad controlling less than a quarter of Syrian territory, a recent survey of Syrian refugees who have fled to Europe found that 70% are fleeing the state organised violence perpetrated by Assad. ISIS beheadings have garnered media attention, but the regime is responsible for deaths of more than three-quarters of the 10,354 civilians killed this year, according to the Syrian Network For Human Rights.

Source: Irin News

Caesar is the pseudonym of a former policeman in Assad’s regime who was initially recruited to photograph crime scenes. When the civil war began in 2011, he was ordered to photograph tortured bodies brought from detention centres to the military hospital. The logic of this performance was to falsely inform families that the deceased had died from ‘a heart attack’ or ‘breathing problems’ in the military hospital.

Between 2011 and 2014, Caesar bravely smuggled out over 55,000 photos of approximately 11,000 Syrians who had been proclaimed enemies of the Assad regime. His images have been exhibited at the UN, the US Congress, the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the European Parliament and at the House of Commons event where Farah and Yasser spoke. The FBI has authenticated the pictures, but Assad denies they are real. The photographs are proof that systematic torture has been inflicted on tens of thousands of Syrians and show that Assad is guilty of crimes against humanity.

One of Caesar’s images.

With everything we know, how can the west maintain its stance of non-intervention? Last week’s Stop the War Coalition talk chaired by Dianne Abbot MP confirmed my impression that the UK is shying away from confronting Assad’s crimes. The panel’s arguments for inaction included the fear of a bigger global war, heightened by Russia’s recent involvement, and the legacy of Iraq.

However, when Syrian and non-Syrian activists tried to speak out on Assad’s crimes, they were not given the opportunity for the entire three hour meeting, despite their protests. Activist Peter Tatchell said afterwards: “I was shocked by Diane Abbott’s unwillingness to invite Assad’s victims to express their opinions. Not listening to victims of Assad’s war crimes is arrogant, insensitive and appalling.” What this reveals is that Assad’s key role in the Syrian conflict does not fit within the larger narrative for the UK’s non-intervention stance in Syria.

While the UK and other states maintain their official position of non-intervention, the Syrian conflict has descended into a full-on proxy war. The network of alliances is too complex to list in full here, but Iran, Russia and Lebanon’s Hezbollah have been doing all they can to support Assad, while the US, UK, Turkey, the Gulf States and others have funnelled money and weapons to the opposition. Despite the vote against military intervention, Prime Minister David Cameron has authorised drone attacks and airstrikes against ISIS targets in Syria – a policy which has been seen to fuel home-grown extremism.

Assad’s claim that he is the last line of defence and an ally in the fight against ISIS seems to have been tacitly accepted in the west. However, his forces has killed seven times more civilians than ISIS in the last four years and analysis suggests the majority of his offensives are directed against other groups. The brutality of ISIS seems to validate Bashar al-Assad’s reason for being and deflect criticism of his own appalling human rights record, while he continues to command the most far-reaching killing machine in the country. His ally Russia’s engagement has just made things worse, being heavily criticised for the bombings of crucial hospitals and killing civilians.

But what to do when the two major forces in the Syrian conflict are so unpalatable? The UK’s supposed stance of non-intervention while it carries out ‘targeted killings’ of ISIS fighters is the worst of both worlds: fuelling further conflict and civilian displacement while failing to meaningfully engage in initiatives that could bring about an end to the fighting. Further bombing is not the answer and boots on the ground could further exacerbate the conflict.

For Rethink Rebuild, a possible measure would be to implement a no-bombing zone to ensure a safe space for civilians and build pressure for peace talks. However, this would require open international intervention, which both the US and the UK have been unwilling to do so far.

The west’s phoney non-intervention stance over the last four years has merely enabled more terror and destruction. Recent peace talks in Vienna have been hailed as a step forward, despite Bashar al-Assad’s absence. However, if we want any meaningful improvement in the situation, the highest levels of government from Washington to Tehran, Moscow, Riyadh, London and elsewhere must be present and transparent about their continued involvement in the Syrian conflict. The desperate situation for ordinary Syrians dictates that humanitarian concerns must take precedent. If their safety is our major concern, stopping Assad’s indiscriminate warfare against his own population should be at the top of our list of priorities.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.