The UK‘s skate prodigies on the sport’s Olympics debut

- Text by Chloé Meley

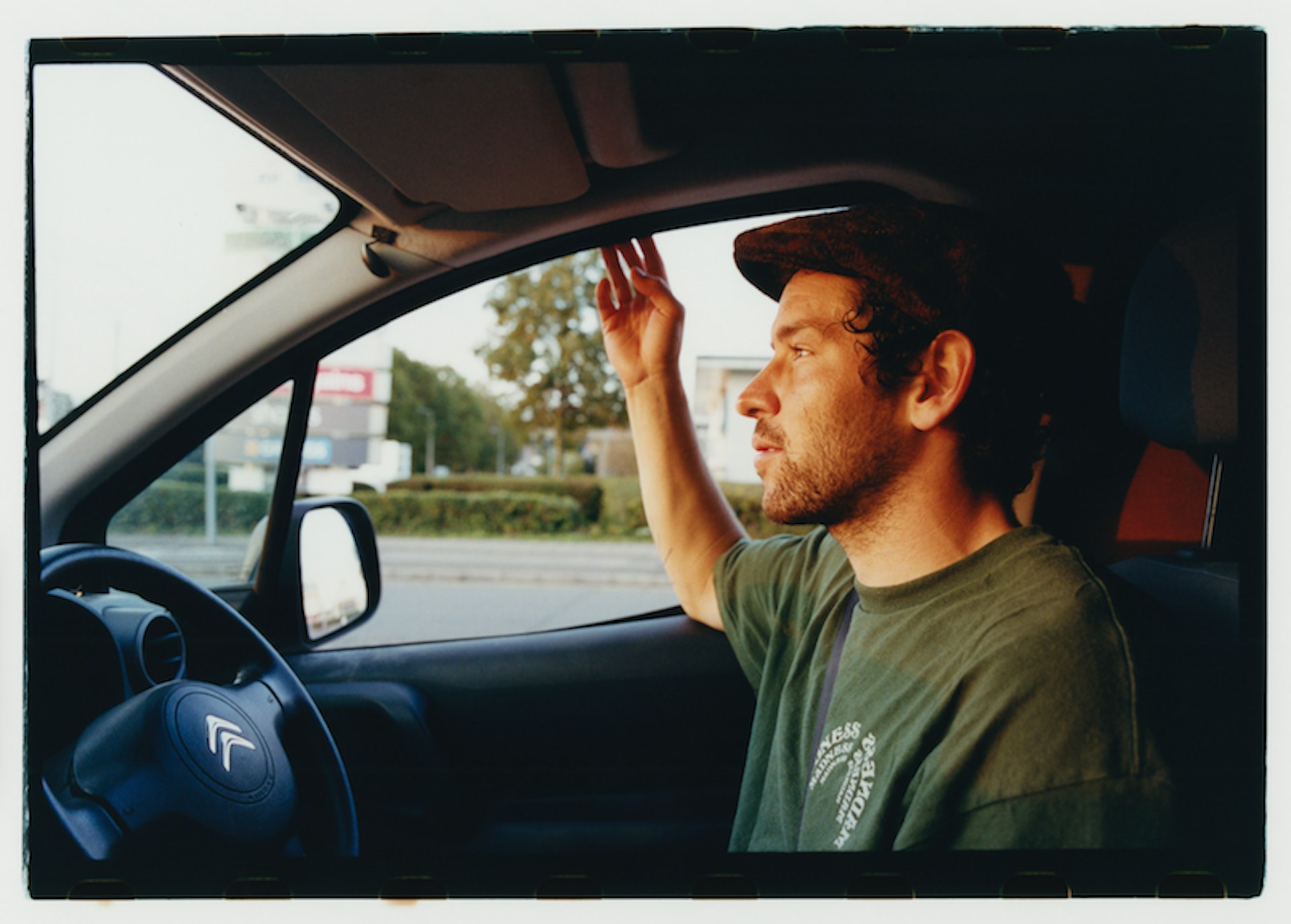

- Photography by Pictured: Jordan Thackeray (left) and Sam Beckett (right)

In the 1950s, flat waves on the Californian coast led to a groundbreaking discovery. Disappointed surfers started gliding around streets on a wheeled wood plank while waiting for the ocean to get boisterous again. In their impatience, they had created skateboarding.

In the decades since, skateboarding has gone global, inspiring fashion, influencing music, creating its own vocabulary, and moulding an entire new subculture defined by camaraderie and an intrepid yet nonchalant attitude. Skateboarding took hold in the UK in the 1970s, as teenagers adapted the activity to rainier weather and bumpier roads, drawing the attention of media outlets attempting to understand this US-imported craze taking over Britain.

There are now around 750,000 people in the country that regularly hop on their boards for transportation, recreation, and in rarer instances, competition. Some skaters have risen above the rest, moving across ramps like they were born with a wooden board attached to their feet and performing mind-blowing tricks with impressive ease.

Despite the athletic ability it requires, skateboarding has long operated outside of the confines of mainstream sports tournaments. But everything will change this summer, as skaters from across the world gather in Tokyo to compete at the Olympics. For the first time ever, skateboarding will momentarily shed its identity as an underground lifestyle to embrace a more conventional status as an Olympic sport – raising questions about what happens to a subculture when it’s thrust into the mainstream.

The new documentary Boarders follows the journey of four of the UK’s best skaters – Jordan Thackeray, Alex Decunha, Sam Beckett and Alex Hallford – as they compete to qualify in the Olympics. Their path is obstructed by injuries, a lack of facilities, and canceled competitions – first due to the Australian bush fires, then to the pandemic.

But their journey is also one that is defined by the power of community. The documentary explores the importance of being surrounded by people who share your devotion and fondness for a certain way of life, having been profoundly shaped by it.

Huck caught up with those four skate prodigies to discuss what skateboarding means to them, their thoughts and feelings on the sport’s debut at the Olympics, and whether a mainstream stage could ever take the soul out of skateboarding.

Jordan Thackeray

As a kid, Jordan had to hustle for skateboarding gear, trading equipment with kids from his estate and inheriting friends’ old boards.

When he thinks back to this time, he can’t remember ever envisioning a world where skaters would become Olympians. “When I was a kid, no one looked at [skateboarding] in the light of it being a sport. Up until recently, we didn’t really think of ourselves as athletic people,” he says.

“The reason I got involved in different competitions was because it was a lot of fun, traveling around, seeing different sites, meeting new people. And then suddenly everyone’s taking it way more seriously. It’s interesting to see the transition.”

But for Jordan, this shift is nothing to worry about. “I think skateboarding will definitely retain its own identity. It’s jumped in and out of the mainstream for decades, but the pure essence of it won’t fade away.”

That essence, for Jordan, is a certain carefreeness, coupled with determination. “You have to be a bit weird to want to do something where you’re probably going to hurt yourself. And skating also doesn’t carry instant gratification. To get to the point where you’re able to control the board even a little bit, you have to put in quite a lot of hours,” he explains. “You have to have this crazy mentality to get into it.”

And the UK skate scene only encourages this tenacious attitude. “It’s a little bit more rowdy than others,” Jordan laughs. “There’s not many places you can go around the world where everyone’s constantly screaming at each other but in a constructive way.”

Alex Hallford

After his dad introduced him to surfing, Alex got into skateboarding at the age of nine. Two decades later, he’s sharing his expertise and love for the sport with children at an indoor skate park in Nottingham. “I love seeing the kids progress,” he says. “Passing on the knowledge is lovely.”

Not only do children learn technical know-how, but also crucial life skills like cooperation and open-mindedness. “The kind of lessons that I teach are very dynamic and inclusive. There are a lot of different ages and different demographics, all kinds of different people that are all connecting when they normally wouldn’t,” Alex says.

He hopes that the discipline’s debut at the Olympics will help change people’s minds about skateboarding for the sake of this future generation of skaters. “We’ve had some terrible weather and grounds and facilities for years, and parts of the general public really have it out for skateboarders,” he says.

“Maybe becoming part of the mainstream will help with things like facilities and general acceptance of skateboarding and skateboarders. There’s a lot of positive things that could come out of it.”

At the same time, Alex doesn’t believe that a couple of tricks done in Tokyo will completely redefine the lifestyle. “Skateboarding is bigger than the Olympics, no offense to the Olympics,” he says. “Some competition to see who’s the best on one particular day, that isn’t really going to change skateboarding much.”

Ultimately, Alex would want skateboarding to remain the fun, rebellious activity that he fell in love with as a kid, rather than a polished Olympian performance. “I hope future skateboarders don’t just see it as some sort of clean-cut Olympic sport,” he says. “I hope it can stay true to itself.”

Sam Beckett

10 years ago, Sam moved to California at 18 to pursue his dream of becoming a professional skateboarder. He came back home in 2019 after a knee injury, and has been based in the UK ever since.

Despite having lived in skateboarding’s birthplace, Sam still speaks fondly of the British skate scene. “In California skateboarding is so integrated into the culture, and it’s a huge industry. In the UK we don’t have those clean parks or clean street spots, we’ve got crusty old skate parks and dirty street spots. But because it’s a small community, it feels very cohesive,” he says. “It definitely has a family feel.”

When asked whether he’d ever considered a future in which skateboarding would be mainstream, Sam takes a second to reminisce. “When I was young, it completely consumed my life. I only watched skate videos and I only wanted to hang out at the skate park,” he recalls. “Because it was the biggest thing in my world, it felt like it was the most mainstream thing ever.”

Perhaps the Olympics will make Sam’s skateboarding bubble a little bit more crowded than before, but he doesn’t mind. He’s not in the business of gatekeeping the lifestyle. “Some people are worried that it’s going to take the soul out of skateboarding, or that something’s going to be taken away from them. But if it’s your thing and you’re enjoying skating, then no one can really take that away from you,” he says. “It’s all up to you, and it’s up to people to make it their own and get what they want out of it.”

“I hope skateboarding continues to provide people with connection. It’s a really amazing tool to experience the world and other people’s cultures and ways of doing things,” Sam adds. “That’s why it’s beautiful, so I hope it doesn’t go away.”

Alex Decunha

When he was a little kid, Alex was walking around the shopping centre in Milton Keynes when he came across a group of skateboarders doing a demo for a brand. “Six-year-old me was just in absolute awe,” he laughs. “And here we are 18 years later, still going strong.”

Alex is what is known as a street skateboarder, which consists of turning the urban environment – with its concrete ledges and uneven slopes – into a skating playground.

“Some security guards think we’re skating here just for the sake of making their life hard. But that’s not the case. Everyone’s pretty friendly within the community and we’re never trying to cause trouble,” he says. “We’re just trying to make the most of it, and sometimes it just happens to be somewhere where you’re not allowed to skate.”

Street skateboarders are routinely chased out of their spots, as stereotypes about skaters persist and the policing of the discipline continues to disrupt their sessions. “Maybe the Olympics will change the public’s perception of skateboarding,” Alex suggests.

He also would like to see the male-dominated sport become more diverse. “I hope it influences a lot of people to get involved and encourages the skate community in the UK to change to become a lot more welcoming, so people don’t feel shy or intimidated at their local skate park.”

“I hope more people try to give it a go because once you’ve tried it, you’ll be hooked from there,” he adds. “It’s a lifetime of good memories sorted just like that.”

Boarders is available now on UK digital platforms.

Follow Chloé Meley on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.