Inside the mind of the world’s most controversial director

- Text by Briony Cartmell

Despite the fact theatre director Milo Rau experienced a Russian travel ban for his exploration of Pussy Riot’s trial; was prevented in Manchester from having naked children on stage for his analysis of child rapist Marc Dutroux; and has recently come under fire for putting out a casting call for ISIS fighters, when I ask what the greatest challenge he’s facing is, he looks nonplussed. “I don’t know,” he says, his typical cheerful manner wavering. “There isn’t really a big challenge in my life. I’m just working.”

For someone whose work The Guardian branded as some of the most ambitious in Europe, such ambition, it seems, is routine.

Keeping Rau busy currently is his premier season at Belgium’s NTGent Theatre. Debuting first is La Reprise, a performance depicting the 2012 torture and murder of Belgian Ihsane Jarfi, a gay muslim man, that caused shockwaves through the country.

The work is deeply arresting and stark in its violence, containing full nudity and live action urination. Rau smiles. “I’m not interested in walking into a perfectly equipped theatre and making a Shakespeare so I can go to sleep under the table.”

Het Manifest van Gent/ The Ghent Manifesto from NTGent on Vimeo.

For work that is so dark, Rau is bright and convivial, with an intelligent twinkle that keeps you nodding along. 10 minutes into our conversation in the Theatre’s cafe, a coffee machine waking up proves too much for a head balancing on the celebrations of the night before, and we run through back corridors, up to the sanctuary of his office. He calls out to colleagues, laughingly swearing at a stubbed toe, and as I tumble gamely behind him, it occurs to me that people are pulled along in his slipstream exactly by that geniality.

It certainly helped to smooth things with the Flemish culture minister after he sent out a casting call for ISIS fighters earlier this year for Mystic Lamb, his new biblical play which is set to premiere in September. Rau tells me the two men ended up bonding over an ’80s song lyric on the minister’s office wall which happened to be by a good friend of his.

Amiability may get him out of scrapes, but his work is lauded critically for thoughtfully tackling trauma. What sounds initially stomach curling – for instance, using disabled actors to recreate the torture-porn work 120 Days of Sodom – becomes comprehensible when deconstructed by Rau.

Milo Rau. Courtesy Phile Deprez

He saw the film, which features extreme violence and brutality, as a young student in Paris and had a revelation: “I understood this violence is happening the very moment in reality somewhere,” he says. “It wouldn’t have made sense to repeat this movie just as Pasolini did with a range of beautiful young Italians, it would just be kitsch today.”

Instead, for his 2017 stage version of the film, he turned to the topic of prenatally detectable disabilities such as Down syndrome where in some countries it is reported high percentages of women choose to abort. “That means these are kind of the last generation of these people, especially in Switzerland,” he explains. “I said OK, I’ll make a play about this sort of fascism, and I will kill them on stage.”

For all his hopping from one trauma to the next, his work is prevented from becoming crass because, underpinning everything, is his early training as a sociologist under Pierre Bourdieu. “He was somebody who said, ‘Immerse yourself – go and understand what you’re talking about. When you’re talking about central Africa, then go live in central Africa.’”

This methodology has created a man of action, bringing revolution to the NTGent in the form of a new manifesto, which I am told is to be woven into the carpet at the theatre foyer, for maximum answerability.

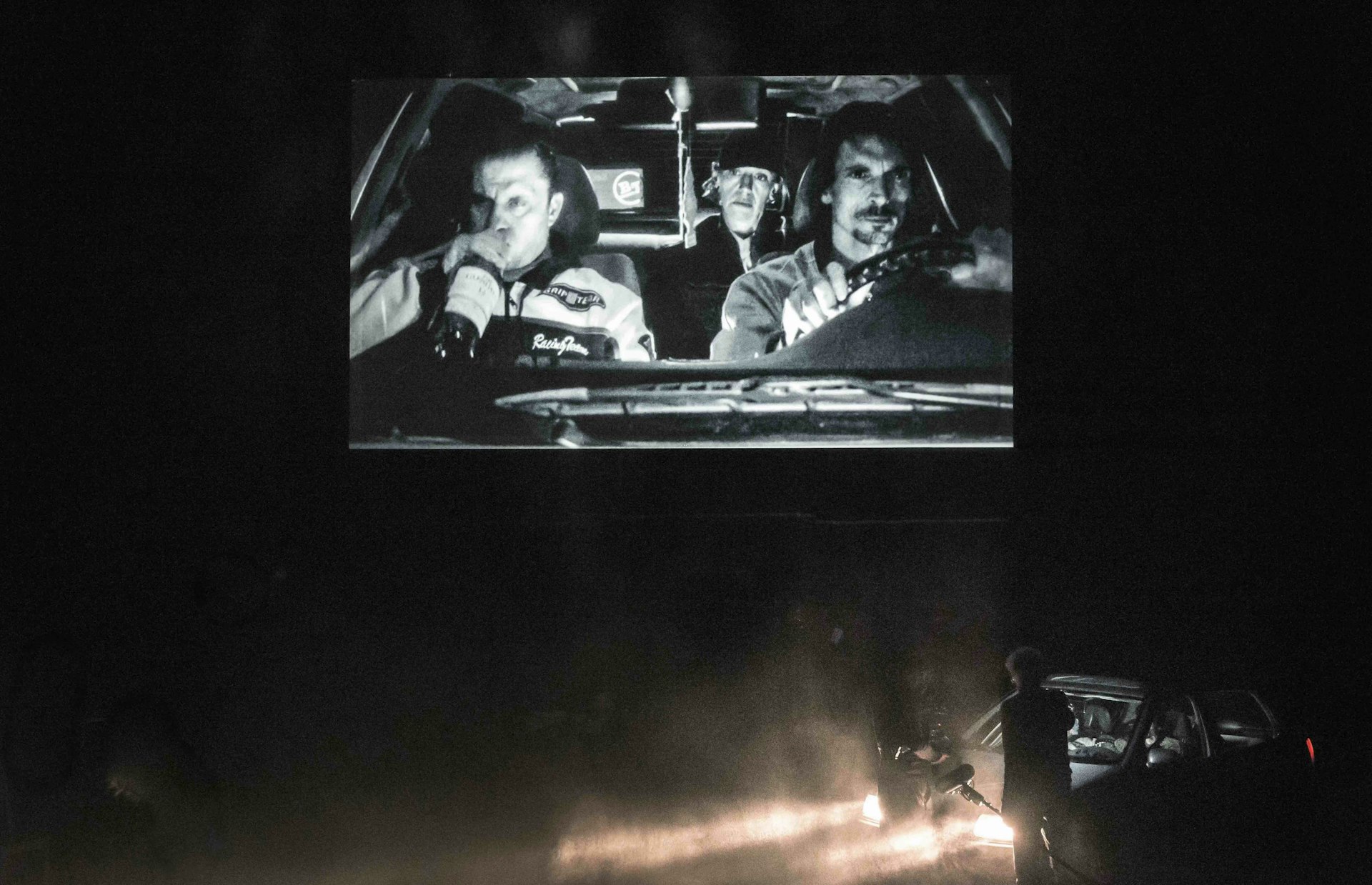

La Reprise. Courtesy Hubert Amiel

Clauses include using non-professional actors, eschewing classical adaptations, and performing works in war zones. “We have no cameramen in eastern Congo, so we take three months to educate some good young photographers from the region and they become our cameramen and so on. In the end, you create a bit of structure, it’s not about touring and saying hello in a war zone then bye bye.”

Rather, what is important to Rau is accountability. After witnessing a massacre of women and children in the Congo, he thought: “OK, I need a truth machine, a machine that explains to me why this happened – because I didn’t understand, it was just children, dead babies, two months the youngest.”

The result was last year’s Congo Tribunal, a performed tribunal with real judges, real experts, real witnesses, and a verdict at the end. It worked: as a result, the minister of interior and minister of mining were dismissed from the government. “It’s started now to become an institution. We invested half a million, we made crowdfunding for four more tribunals and then ten more which will happen in autumn.”

La Reprise. Courtesy Hubert Amiel

It is this making sense of violence that rounds back to the murderous subject of La Reprise; although he stops short of definitive causality, Rau points to a backdrop of unemployment and the collapse of the metal industry in Liège, Belgium. “Sociologically it’s simple,” he says. “You can really see the connection between that loss and how the whole city falls into depression and anger. On the other hand, if you give a group of young men the possibility to be violent, they will.”

“One day after the men [killed Jarfi], they continued to live as if they hadn’t and that’s interesting. When society has this behaviour that’s normal and behaviour that’s extraordinarily sadistic, if civilisation doesn’t draw that line again and again by practice, then it becomes fluid.”

But where does theatre stand in drawing that sadistic line?

Rau speaks very softly. “Artistic freedom has its limits, of course. These are the limits of laws on construction, of physical possibility. You can’t kill on stage, you can’t have criminals. In Lam Gods, a sheep is killed and we asked ourselves: why don’t we kill a sheep every evening because they are killed anyway very close to the theatre? We said ‘OK, this could be interesting.’ But it’s forbidden, you can’t do it.”

Rau knows what he can’t do but in creating his truth machine, he’s leaning into the limits of what people can handle. The greatest challenge, then, lies at the feet of the audience.

NTGent’s Histoire du Théatre (I) La Reprise is touring from 7th July 2018 in France, Germany, Switzerland and Luxembourg.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.