The creators of Black Mirror want you to stop worrying

- Text by Daniel Dylan Wray

On September 23, 1984 a young Charlie Brooker saw something so terrifying that it would leave its mark on him for life.

At 9.30 on a Sunday evening, Charlie – 13 years old at the time – sat down to watch television. What followed – the apocalyptic war drama Threads – left him slack-jawed and frozen stiff. The BBC show tapped into a collective fear, using the backdrop of Sheffield to show what life would look like if a nuclear bomb were detonated.

“It had a big impact,” says Charlie, now 48 and best known for his own harrowing TV series, Black Mirror. “I was already a worried person and I could not understand at that time – with the world appearing constantly on the brink of nuclear war – why everyone wasn’t running around screaming. It felt like there was a crisis going on and alarm bells should have been ringing at all times.”

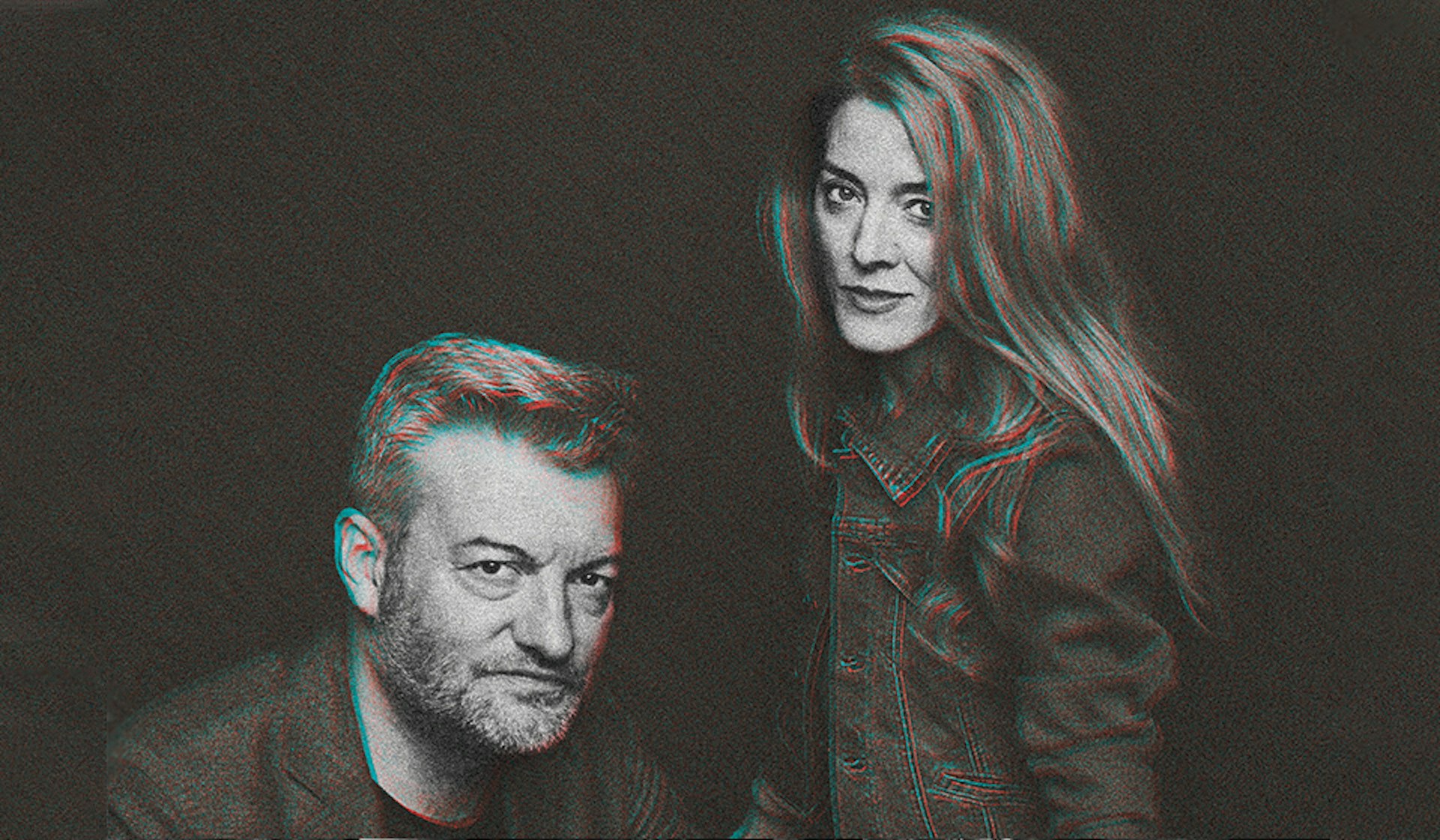

That memory of watching people rummage around in the nuclear fallout, eating rats to survive, never really left him. “That has probably translated directly into a lot of the unease you see in some episodes of Black Mirror,” says Charlie, sitting in a plush Soho hotel alongside the series’ co-creator and producer, Annabel Jones. “That, and the sort of laughing-into-the-abyss type flavour to the comedy stuff I’ve done. I think they’ve both been born from the same traumatic shape the world was in back then.”

“When you think back, it was fucking traumatising,” says Annabel, nodding. “To think that we were all on the verge of nuclear war.”

Annabel and Charlie have been working together since 2008’s Dead Set, the ostensible blueprint for Black Mirror, which followed the contestants of a fictional Big Brother-style house while a zombie outbreak ravaged the outside world. Since then, the pair have taken Black Mirror from a cult Channel 4 series into a global Netflix mega-hit that attracts big-name talent (Miley Cyrus features in the latest series, while Jodie Foster has been a previous director).

Although the show explores our relationship to technology by tapping into the dark possibilities of an increasingly connected world, Charlie’s background is rooted in humour. Growing up in a Quaker household in the Oxfordshire village of Brightwell-cum-Sotwell, he remembers his father steering him towards groundbreaking comedy shows such as Not the Nine O’Clock News and Monty Python. In 1999, after failing to graduate from the Polytechnic of Central London (his media-studies dissertation on video games was rejected), Charlie launched a fake TV-listings website called TVGoHome.

One recurring entry evolved into a real sitcom (Nathan Barley, co-created with Chris Morris) and Charlie soon established himself as an acerbic television critic for The Guardian as well as a presenter for a variety of TV shows – Screenwipe, Newswipe and Gameswipe – where his apocalyptic anger took aim at life on-screen. Annabel – who grew up in rural Wales and studied economics before pursuing a career in TV production – played a crucial, ever-present role on many of these shows.

In person, Charlie is the more loquacious of the two, often quicker and more eager to answer questions, which he does through rapid bursts of words (usually laden with dark humour and profanities). In a smart suit jacket, yellow polo shirt, jeans and skate shoes, he shuffles about, crossing and uncrossing his legs, often gesticulating to emphasise points.

The antithesis to Charlie’s animated restlessness, Annabel sits curled up on the sofa like a snug cat in a suntrap. She is more held-back in her responses, often letting Charlie take the lead, though frequently chipping in to contribute digs at his expense. At one point, the two get locked into a playful back and forth, bickering about whether we are in more or less danger of nuclear attack now compared to when they grew up. It’s clear that their creative and personal relationship is built on a deep-rooted love of prodding one another to extract ideas, as well as a ceaseless impulse to take the piss.

“That’s how he found God,” Annabel quips, when asked how the pair unplug from the bleak imaginary world they often inhabit to create the show. “Black Mirror is the word of God – he speaks through me and makes me do things,” Charlie retorts, keeping the joke alive before answering more seriously. “Part of me is contrary. I’ve always been a worrier, and Black Mirror is born out of me being worried about certain things. Oddly, when other people start worrying I start to think that I can ease up a bit on my worrying. In a contrarian way, I start to look for an optimistic point of view.

“So, you can look at the fact that the world is going to shit,” he continues. “But we are so bombarded with news reports and mini-updates – you absorb more news and know about what’s going on in the world more than ever – that it makes everything feel like an emergency and a crisis.”

Anthony Mackie and Yahya Abdul-Mateen II in Season 5 episode ‘Striking Vipers’

When it comes to how people avoid this kind of information overload, Annabel – as she does often through the conversation – quickly flags up the paradox in play. “It’s the relationship [with devices] that people worry about most, which is hilarious,” she says. “I love the irony that now phones and devices are reflecting this and telling you how long you should be using the devices for. It’s like the drug is also giving you the nicotine patch.”

It’s an apt analogy for Charlie’s own reliance on technology. A former heavy smoker who would reach out and grab a cigarette first thing in the morning “without thinking”, he has since observed himself replicating the same routine with his phone. “It’s a comforting, familiar thing,” he says. “I have to remind myself to set a good example to my kids by not using it all the time. But sometimes kids are boring. They can be really fucking boring. They are not always good conversationalists – their experience is narrow. I remember hearing one of them say for the first time, ‘Daddy put your phone down’, and you feel pretty bad. It’s something everyone is grappling with.”

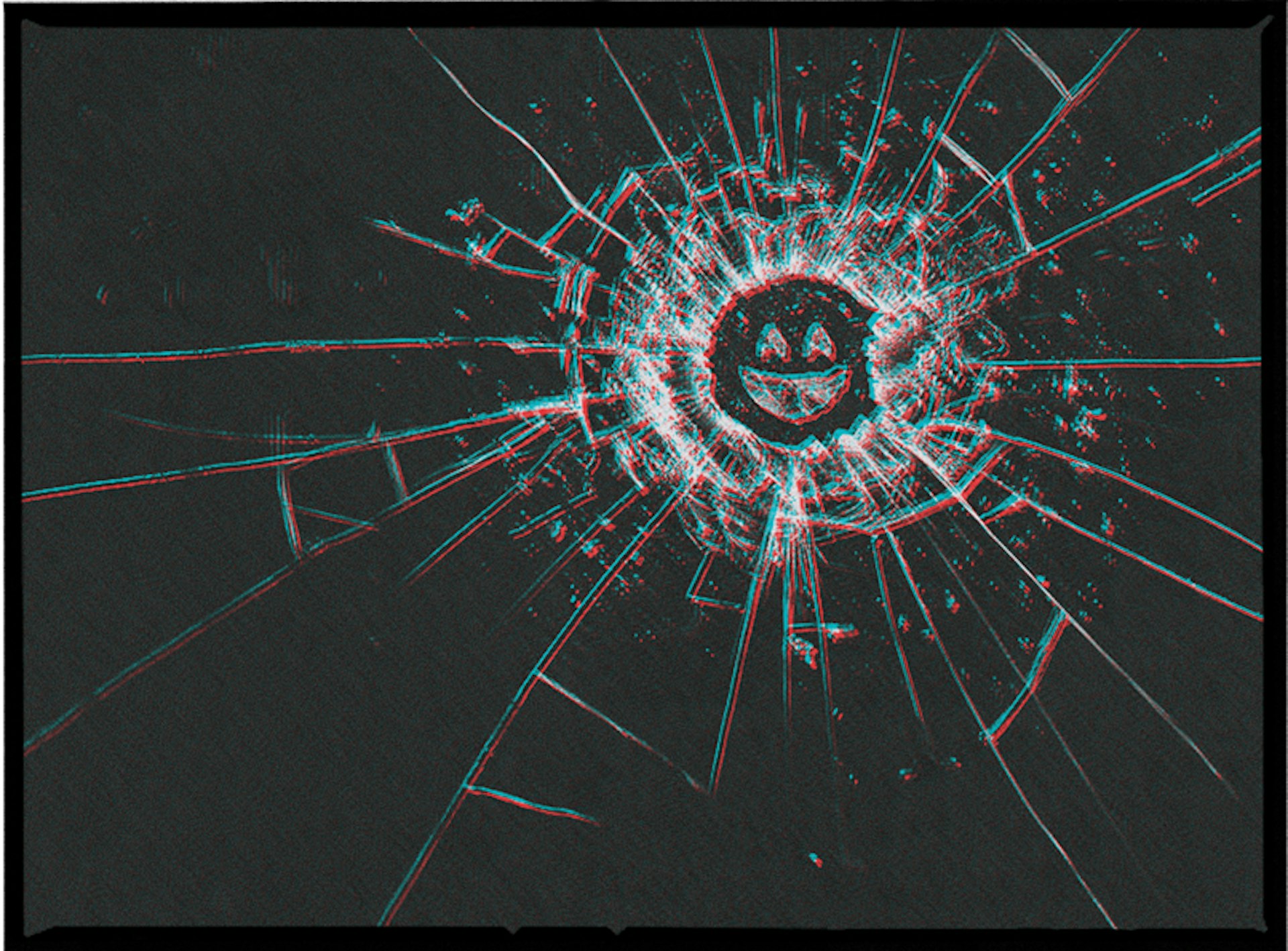

Over the years, Black Mirror has dealt with a variety of subjects – each episode features its own story with new characters. It’s an approach that has led to fresh, distinctive worlds being created time and time again. Yet while the appeal of the show often stems from its dark shade of realism – technological advances and nightmare scenarios that feel within the grasp of possibility – sometimes those subjects veer a little too close to real life.

Four years after the show’s first episode (in which the British Prime Minister was made to have sex with a pig on live TV), for instance, then-Prime Minister David Cameron was accused of defiling a dead pig’s head. But some episodes have become even more uncomfortably prescient. ‘Nosedive’, taken from the show’s third season, imagined a world in which everyone was constantly ranked in order to reflect their social status. In the real world, China’s ‘social credit system’ closely emulates that same practice.

“For ‘Nosedive’, Charlie had the idea about eight years earlier and then Uber came out and we were like, ‘Fuck, we’ve missed it – too late,’” says Annabel. “But in the end, it benefited from it because it was already there in a small way so the story was expanded into the personal.”

“When we were first discussing the idea,” Charlie chimes in, “it would have been very abstract. But then when it came out, everybody was like: ‘Oh God, that’s my life.’”

Charlie says that the basis for many Black Mirror episodes comes from finding a hilarious situation and then turning that into a drama by stripping away its comic roots. Yet, somehow, that humorous foundation always remains intact. So at a time when reality can often feel more farcical than fiction, and political turmoil so grim that humour can’t be extracted from it, could we be entering a post-satire era?

Bryce Dallas Howard in Season 3 episode ‘Nosedive’

“I don’t really like the word ‘satire’ because to me it just means taking the piss out of the real world,” Charlie says. “We do that a lot in our episodes but I never expect it to change anything. Satire doesn’t actually ever really change anything. At the moment, the real world so resembles The Day Today or Brass Eye that I don’t think you’d ever write anything as on the nose as Donald Trump. You’d never write Brexit the way that it has unfolded. I don’t think we’re in a post-satire world, I just think the word is redundant.”

Charlie can’t help bouncing around on the sofa as he talks – an upbeat energy that shines through no matter how dark the conversation gets. In fact, for someone who freaked out about the prospect of nuclear war at a young age and then built a career from his own predictions of how the world may end, he’s surprisingly optimistic about the future.

“We’re in a time where you have huge progressive movements going on, so it’s not all bad news. It’s an interesting time to be alive but, hopefully, it’s a transitional time. I don’t think this is the spiral towards the end because people are still joking about it. The point where it really is the end comes when nobody is laughing.”

This article appears in Huck: The Burnout Issue. Get a copy in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Season 5 of Black Mirror is available on Netflix.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.