Why don’t video games take sex seriously?

- Text by Tom Faber

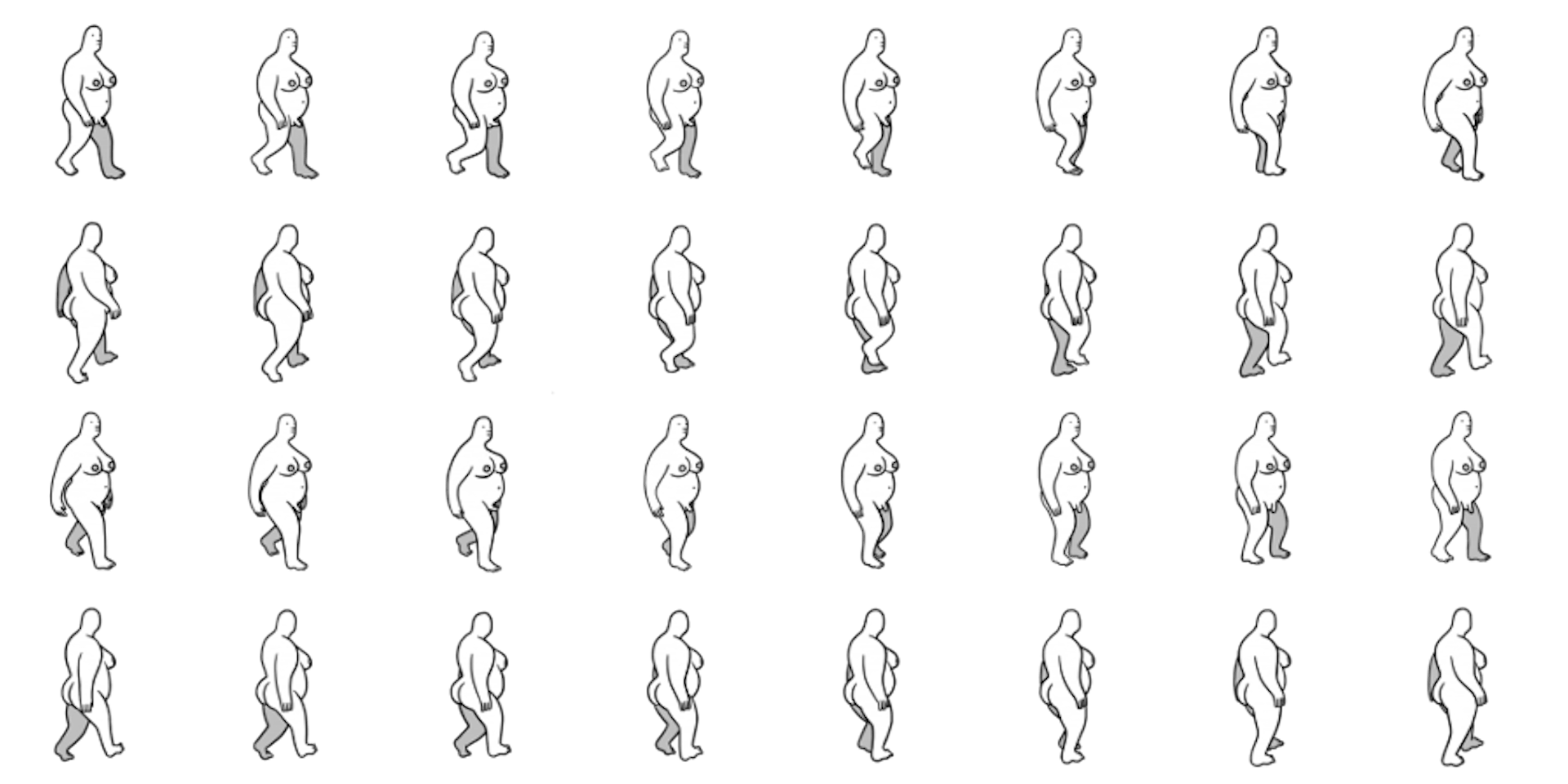

- Illustrations by Eleanor Davis and Robert Yang from ‘We Dwell in Possibility‘

It starts with a single nude figure: tiny, cute, like a Jelly Baby with genitals, strolling around an Edenic garden. Then another joins, and another, and soon my screen is full of naked people spanning all genders, skin colours and body shapes. This “queer crowd simulation game” is We Dwell In Possibility by independent game maker Robert Yang and illustrator Eleanor Davis, which launched last month as part of Manchester International Festival’s digital program.

Sometimes the Jelly Babies have sex, letting off a gush of red hearts. This wholesome orgy is notable because video games so rarely engage thoughtfully with the subject of sex. Yang is one of a small, diverse group of creators who are introducing meaningful explorations of sexuality to gaming, particularly highlighting the queer, kink and BDSM communities. They are joyously redefining what it means for software to go hardcore.

For as long as there have been video games, there has been a seedy niche of video game porn. But games outside of porn which feature sex are relatively rare, and most are deeply problematic. From 1982’s Custer’s Revenge, in which the objective is to rape a Native American woman, to 2010’s God of War III, where the thrusts of your hero’s copulation are accompanied by the sound of a sword slicing air, followed by a post-coital boost in experience points.

We Dwell in Possibility – Illustrations (c) Eleanor Davis and Robert Yang

The artistic legitimacy of games has been compromised by decades of this objectification: women dressed impractically in chainmail bikinis, gratuitous sex scenes used as in-game rewards as if women were missions to be completed. Yet even these problematic examples are few and far between. In most games, even those with adult themes, sex is conspicuously absent. Why does this medium struggle so much with sex when it has no issue representing mature themes like violence?

“A big part of it is warped American values forcing themselves on the rest of the world,” says Ryan Rose Aceae, a creator of indie games which explore sex and gender. “We have this puritanical culture in which violence is okay but we can’t show sex – anyone can buy a gun, but god forbid women show their breasts in public.”

“It also links to our stigma against sex work. It’s okay to pay money to live out the fantasy of killing another person but not to pay for a sexual experience, even one in a game. It’s seen as pathetic, and people assume that a virtual sex experience is sought only by people who can’t have sex in real life.”

Games are further held back by the lingering stereotype that they are made for children. Despite the fact that there are an estimated three billion gamers on earth across a broad spectrum of ages, with many interested in mature themes, big companies are reluctant to take sex seriously. This is partly a financial decision: including graphic sex will land a game with an 18+ age rating, which could restrict where it’s sold, damaging profits. Yang’s games have been repeatedly banned from Twitch, other sex game makers are blocked from Paypal. “There is an anxiety, which increases as game companies get bigger, about being perceived as juvenile, depraved, or a bad influence on the youth,” says Naomi Clark, game designer and Chair of NYU’s Game Center.

Even if there is a desire to show sex in a game, there are myriad technical limitations. Video game sex scenes, when they aren’t problematic, are notoriously unsexy, with body parts overlapping glitchily or characters coming together with all the tenderness of a child smashing naked dolls together. Bodies in games don’t feel soft, Yang points out. They are made for running and shooting, not holding hands or kissing. “I could make a shooter in five minutes,” he says, “but if you tell me to make a hugging game, that’s really hard. Designing intimacy, closeness, simulating objects touching slowly – these are really hard in game development because so little attention has been paid to this space.”

There has been some progress in mainstream games over the past decade. The first step was an acknowledgement that sex is not always serious – games like The Witcher 3 showed that it can also be humorous and awkward, with a notorious sex scene astride a stuffed unicorn. These titles have not always been inclusive enough, however. “Sex in games can be fun and fantasy-fulfilling, but the question is: whose fantasies are we fulfilling?” asks Michelle Clough, game writer with Talespinners and chair of the Romance and Sexuality special interest group of the International Game Developers Association. “The answer is always straight dudes, because the assumption is they’re the only ones who get horny. These preconceptions could not be more wrong.”

Role-playing games such as Mass Effect and Dragon Age from developer Bioware excel in nuanced depictions of romance, including those between same-sex and even inter-species couples. Still, such romantic side-quests always follow the same tired formula – you meet possible love interests, decide which one to pursue, jump through hoops, and are rewarded with a sex scene. “Games are starting to experiment with sex as a marketing and titillation strategy,” says Yang, “but they’re not actually interested in thinking about sex in any deep way. It’s more like: here’s a penis on your character, now go shoot some people.”

Such limitations are particularly frustrating because gaming has inherent qualities as a medium which could allow it to explore sex in ways that would be impossible in TV, film, or books. One is a unique potential for empathy. While you passively watch a character in a movie, in a game you make their decisions – you are them – meaning you identify more deeply with their story. Players inhabiting game characters are free to explore their desires in a safe space with no real-world consequences.

A new wave of indie creators are capitalising on this potential for self-exploration with sex games in the visual novel genre, which minimises complex gameplay to tell its story largely through text, images and narrative choices. Notable titles include Tusks, a queer dating game about orcs, Dream Daddy, about dating gay dads, Hardcoded, a cyberpunk story of trans awakening, and Ladykiller in a Bind, a queer adventure exploring kink and BDSM. The range of options is dizzying. “The scope of human desire and depravity is so beautifully wide,” marvels Yang.

For these games, sex-positivity is essential to their queerness. “Sex is part of what makes us queer,” says Clark. “It’s can’t be a sanitised, ‘no kink at pride’ version of gay liberation. No, we’re going to have sex in these queer games.”

While these visual novels tell diverse, meaningful stories around sex, they do not capitalise on gaming’s full potential to explore sex because they have little actual gameplay, meaning the sex act is a passive experience that the player watches. Creators are only now exploring the foothills of what interactivity can truly offer. Yang is a pioneer in this respect, with a range of crass, funny, thoughtful games that ask you to manually scrub a naked hunk in the shower, pleasure a gay car, or fellate an anonymous dude’s firearm in a public toilet.

There are two main factors contributing to the blossoming of sex games in the indie space. One is the recent availability of tools which allow independent creators to make games cheaply and with little technical knowledge. The low financial stakes mean it’s easy for independent creators to bypass gatekeepers in game publishing and pursue passion projects. It has also paved the way for the second factor, which is the increased presence of queer, female and POC creators in game development, particularly within the indie space. “These are the people pushing sex forward in games,” says Aceae, “straight white male developers don’t need to challenge anything, because games already cater to their sexuality.”

There is still a question around how explicitly indie games can show sex before they blur into the separate world of less artistic porn games which are mainly found on Nutaku, a platform owned by MindGeek, the parent company of Pornhub. Such games are generally seen as cheap and shallow. “Maybe disdain of porn games isn’t because porn is inherently bad,” says Clough, “but because the types of porn endemic to this genre are bad. I go onto Nutaku and what do I see? Boobs boobs boobs, boobs boobs boobs, then some bodily fluids I don’t want to consider – and I leave. Porn game designers may need to rethink their approach. Just because it’s porn, it doesn’t mean it can’t be interesting or meaningful.”

Engaging maturely with sex does not delegitimise gaming as an artform. It acknowledges games for what they truly are – engines for pleasure and play, tools to explore our fantasies. Games can help normalise diverse sexualities and tastes, even imagine the future of sex. As they grapple with sex, we see them maturing as a medium. Still, outside the indie space, the mainstream’s concessions to modes of desire which are not chaste or heterosexual are severely limited. Yang calls them crumbs. “I’m tired of these crumbs. It’s fun to lick crumbs off the floor, right?” he says playfully, “fun and hot and sexy. But let’s bring our heads up a little bit and eat from the table sometimes, too.”

Follow Tom Faber on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.