A trip down Greek Street, old Soho’s final frontier

- Text by Jessica Furseth

- Photography by Theo McInnes

I know exactly where I was when I realised there was something different about Greek Street – a road on the Eastern edge of Soho in London, running from Soho Square down to Shaftesbury Avenue. It was just before Christmas, not last year but the year before, and I was with my mates Ross and Gemma and we’d wandered over to Greek Street from the more generic parts of Soho in search of one last drink. There’s that place behind the bookshelf, I’d said, referring to one of the many unmarked bars of Soho. But of course we couldn’t get in – one of the best things about the bar behind the bookcase is that they don’t ever let it get crowded.

So we wandered down Greek Street. Soho was even more crowded than usual as seemingly every Londoner was there, getting merry on a Wednesday. Soon we reached Norman’s Coach & Horses, an old-man pub of the finest order, and grabbed an outside seat. But as I went inside to get a bottle of wine I realised this wasn’t just some rammed Soho pub: everyone in there was singing Oasis around the piano: “Slip inside the eye of your mind / Don’t you know you might find / A better place to play?” Maybe you had to be there, but the moment felt euphoric, and I fell in love with Greek Street right there and then

It’s just before Christmas 2018 when I meet with Alastair Choat, landlord of the Coach & Horses. We rendezvous in a pub over a lunchtime drink – not The Coach, mind, because it’s Christmas Eve and if we were in there, people would be knocking on the windows asking to be let in.

Choat, a tall guy in a Bowie shirt and chunky silver rings, took over the freehold of the 1847-born, Grade II-listed pub eight years ago when “London’s rudest landlord” Norman Balon retired after 63 years.

Alistair Choat

When they first met, Norman told Choat to ‘fuck off.’ But eventually they got talking, and Choat won him over. Norman, now 92, still comes in every other Wednesday to collect the new Private Eye (the magazine holds its legendary fortnightly lunches at the Coach). “Norman told me once, in his gruff voice, ‘We’re not friends Alastair, just very good acquaintances.’ I’m happy with that – a man of his stature tolerates me!”

The Coach & Horses, with its blonde wood and red-tinted lighting, is a talking pub: there’s no music there apart from the piano-led singalongs. “We are an old fashioned boozer,” says Choat. It’s a friendly place and not just for old men – the mix of people has never been greater and there’s even a vegetarian dining room upstairs now. Asked how that went down with the regulars, Choat says it made no difference as they’re not the ones eating: “They come to drink and talk. To them, eating’s cheating!”

A bit further up Greek Street is the Pillars of Hercules, another classic boozer stemming back maybe as far as 1714, that made everyone very nervous when it closed last February for refurbishment – a word that rarely bodes well for a pub. Now, the outside looks the same – the sign with the bare-chested Hercules pushing those pillars is still swinging – but alas, inside the floor is no longer sticky and neither is the air. I used to go to the Pillars, a trusty old pub where you could always get a seat, with my mate Gavin, who described the smell in there as “stoic” (I’d call it “cheesy”). But now, it’s positively floral in there: the Pillars has become “Bar Hercules” and has an actual cocktail menu. Choat chuckles when I tell him this, and assures me he won’t refurbish the Coach: “I like it as it is. It’s rough around the edges and the toilets aren’t that great, but the atmosphere is fantastic.”

*

My view of Greek Street as the last great, ‘shit’ street in Soho is actually a very old idea. In 1906, a Metropolitan Police Inspector called it the “worst street in the West End of London” – a place where “crowds of people gather nightly who are little else than a pest… some of the vilest reptiles in London live there or frequent it.” But what a delightful bunch of reptiles it is.

“Soho has always been quite a dynamic, un-deodorised kind of place that welcomes creative oddities, but not bores,” says Choat. “How you differentiate between the two is completely up to the people in Soho.”

Soho is a small patch of London – about three-quarters of a square mile bordered by Oxford Street, Charing Cross Road, Shaftesbury Avenue and Regent Street. It was grassland until Henry VIII took possession in the mid-1500s and turned it into a royal hunting ground (the word “Soho” is a hunting call: “Sohoe, the hare ys founde!”)

As efforts to turn Soho into another Mayfair in the 1700s failed, it became a village of bohemians, writers, troublemakers and immigrants. While the area has come a long way from poverty-stricken Victorian lodging houses and red light districts, its reputation as London’s hedonistic core set the scene for what Soho is today. This was the place for rockers, teddy boys, skiffle fans, Mods, Punks and New Romantics. By the time the ’60s hit, Soho nightlife was transformed, welcoming people of all classes, races, sexual orientations and gender identities.

Greek Street was first mentioned by its current name in 1679, taking its name from a Greek church from 1677 on Hog Lane (now Charing Cross Road) whose main entrance faced Greek Street – immigrants (French, Italian, Jewish, Greek and more) were plentiful in Soho at the time. Greek Street comes first in the old cabbie mnemonic ‘Good For Dodgy Women,’ which is how they remember the order of Greek, Frith, Dean, Wardour. The air smells like beer, cooking grease, soy sauce, and piss. Casanova is said to have lodged at number 47 and Thomas De Quincey, who wrote Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, is said to have stayed at number 58. Greek Street is not a long road – three, four minutes’ walk from 1862 homeless charity House of St Barnabas at the top (where Dickens supposedly wrote A Tale of Two Cities) to the Palace Theatre at the end. While the sex trade is far less prominent in Soho than it used to be, there’s at least two or three “walk-ups” still on Greek Street, with subtle handwritten signs in doorways advertising “models.”

*

I meet with Tony Shrimplin, Chair of the Museum of Soho, who invites me for a wander down Greek Street. There are about 3,000 local residents currently living in Soho but it used to be more like 30,000 back in the 19th century, says Shrimplin, an unassuming man who walks with a cane (we keep getting stopped by people on the street as he tells me he’s “part of the furniture.”)

Asked what the Soho spirit is, Shrimplin says it’s all about the people: “A big part of what I love about Soho is that you can have a place where the sky’s the limit for the bill, and a few doors down you can get a meal for five quid. It’s really important to keep that – Soho is for everyone.”

Shrimplin says the area still has a clubby vibe to it, but there are far fewer live venues and Crossrail has been challenging – he refers to the loss of the Astoria to make room for a Crossrail station on top of Dean Street. Thanks in large part to the efforts of the Soho Society, which formed in 1972 to stem the tide against change, Soho is a Conservation Area, but developers are chipping away: “It’s a shark attack.”

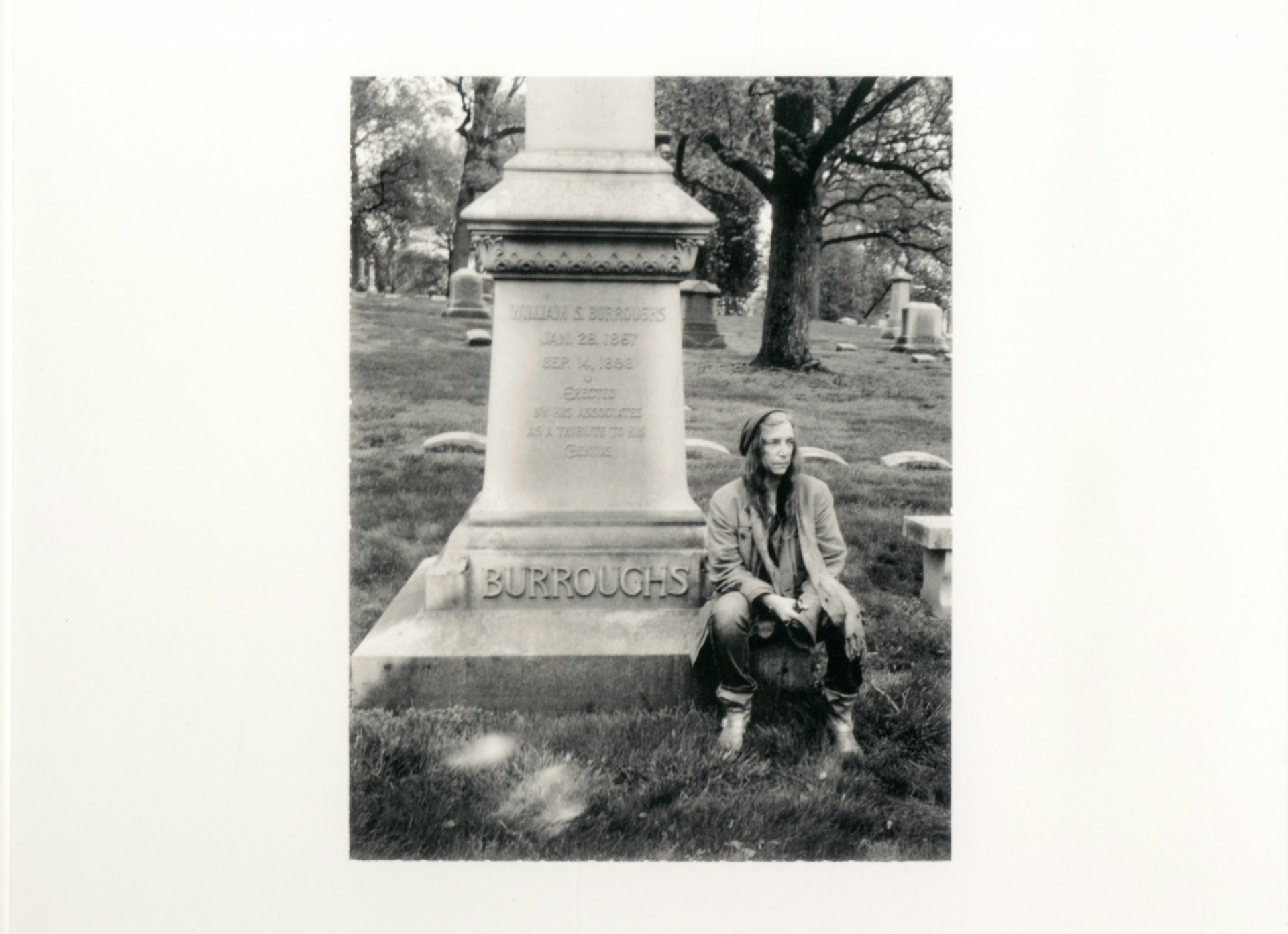

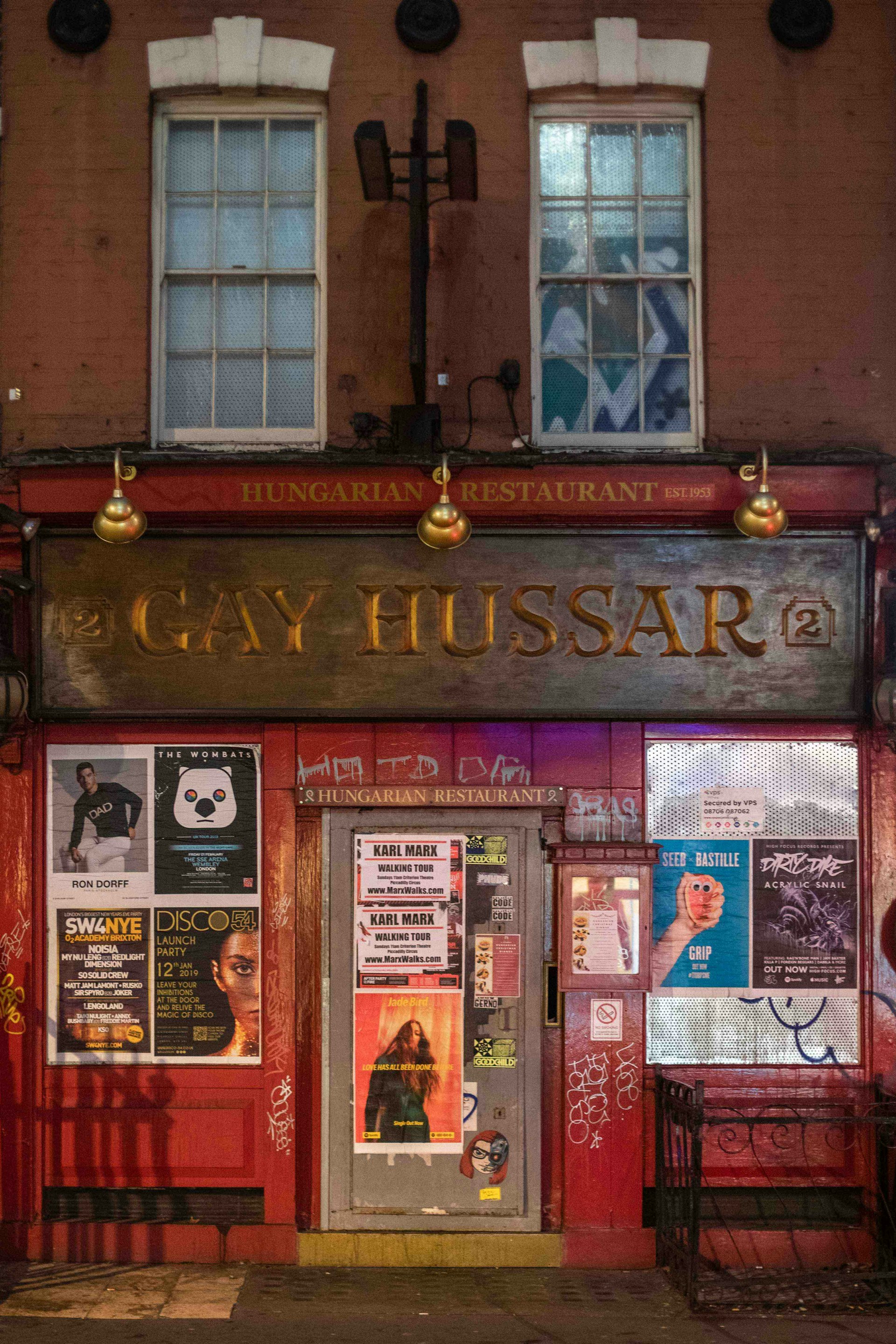

Shrimplin is pragmatic about change, though: “You can’t keep the area in cotton wool. Soho is a living, working part of London, and change is inevitable.” Rents and business rates are high in Soho, businesses come and go and no one is immune: Greek Street stalwart and political gossip hotbed the Gay Hussar is boarded up after serving its last goulash in June. Shrimplin points out a white-fronted building that’s just been done up: number 59 was once the Soho Club and Home for Working Girls, not far from another development where the 19th century fronts are all that’s left of the old Wedgwood pottery showrooms.

Tony

Tony Shrimplin

Iconic Soho deli Lina Stores, which has been trading from Brewer Street since 1944, opened a restaurant on Greek Street last spring at the site of the old Trattoria Da Aldo, which had been there for 42 years. There’s a new-ish restaurant and tea room called Bun House – neither Shrimplin nor I can remember what was there before: “Once a place goes, even as a local you can forget, especially if the last place hadn’t been there long. There’s a constant change.”

Right next to it is the charming Pleasant Lady Jian Bing Trading Stall, a hole-in-the-wall outlet for jianbing, a Chinese savoury crêpe. A classical meal can be had at L’Escargot, London’s first French restaurant from 1927 whose tricolour neon sign still lights the way. Also on Greek Street is Maison Bertaux, probably the oldest French patisserie in London, established in 1871 when Paris Commune-supporter Monsieur Bertaux fled with a handful of recipes. Tania Wade, sister of current owner Michele Wade, has a small gallery upstairs, says Shrimplin, although you wouldn’t know from the outside.

There are many Greek Street wonders that you won’t know are there unless someone told you. For example, the cocktail bar behind the bookcase (which I did manage to get into in the end) – its proper name is The Vault, and it’s just below Milroy’s of Soho, the whisky specialist established in 1964 by brothers Jack and Wallace Milroy. “They were the first to bring single malt scotch into London – they used to go up to Scotland in a van and pick it up,” says Martyn “Simo” Simpson, who’s owned Milroy’s since 2014 which is when he opened The Vault.

“Our very simple ethos is whisky without the bullshit. Milroy’s was always about drinking whisky regardless of how much you earn, where you’re from, where you live, and that’s what we’ve changed it back into,” Simpson tells me, as we’re sitting in the bar before it’s open. A young-ish man with messy blond hair and arms full of artful black tattoos, Simpson agrees that Greek Street is something special – he bought Milroy’s after a few years in corporate ownership. He thinks Soho had started becoming too commercial and “a bit boring” around five or six years ago, but then the Save Soho campaign happened and things began improving. “We’ve got that old Soho spirit back: zero bullshit, just enjoy yourself and have a good time.”

At street level, Milroy’s is a shop-slash-bar that takes whisky very seriously. Simpson says there are 400 whiskies in the shop and 300 in the bar ranging from £5 to £200 a glass. The curated selection changes constantly, but the staff knows every one. Walk past and push through the bookcase in the back and the cocktail bar reveals itself to the lucky who can get in – or the smart who’ve booked ahead.

When I visited, Greek Street was packed – Soho before Christmas is just like Soho in summer – and my boyfriend and I had to queue to get into Bibimbap at number 11 for a nice, cheap Korean dinner in burning hot stone bowls. The Greek Street pubs were as rammed as the Tube in rush hour, but none of that busyness followed us down into The Vault – this is seated drinking only. The easy atmosphere with low lighting and quiet-ish music, coupled with table service, was a welcome reprieve from the world outside.

*

The top end of Greek Street is full of music and entertainment history, some of which is long gone. Legendary folk music venue Les Cousins used to be downstairs at what’s now Club 49: “Bob Dylan and Paul Simon played there – Les Cousins had a significant hand in the resurgence of folk in the 60s,” says Shrimplin. “Diana Matheou ran it with her husband, she still lives in Soho.”

He stops in front of the Be At One bar, remembering it was the site of Le Beat Route in the 80s, a New Romantic club where Spandau Ballet used to go to see and be seen: “You go down Greek Street / Then it’s underground / Well it’s Soho life”. A corner where retro clothing is now sold used to be Soul Jazz Records, now at Broadwick Street. Comedy fans will note the plaque over Zebrano’s marking it as the site of the Establishment Club from 1961, run by “only twin” Peter Cook. (His wife Wendy described their first sight of number 18 Greek Street: “It was the seediest of beer-sodden atmospheres. The windows were swagged in oceans of red velvet curtains … there were discarded G-strings, used condoms, plastic chandeliers – all the tawdry remnants of a former strip club.”)

House of MinaLima at number 26 is a Greek Street newcomer. The showroom for graphic design duo Miraphora Mina and Eduardo Lima is primarily dedicated to the Harry Potter franchise, and the building had been a popup venue before the House of MinaLima opened in 2016, initially as a temporary exhibition.

“We took root, and we totally couldn’t leave now,” Miraphora Mina tells me. While she says the location isn’t great from a retail perspective, the bottom end of Greek Street feels safe and cosy: “I never thought having a business right in the centre of London would feel so village-y. It’s really lovely. I always feel at home when I come here.”

This village spirit did mean that, at first, Mina was a little concerned about possibly threading on toes – other businesses had been there for so long. But she found a warm welcome: “That first summer there was this torrential rainfall and everyone got flooded, and we shared each other’s pain and helped each other.”

Mina is a fan of the Japanese Knife Company at number eight, a shrine to knives with 2,500 blades to choose from – this is a destination shop for people who mean business. Owner Jayesh Patel assures me they use his knives at L’Escargot across the street: “Virtually any fine dining restaurant in London uses our knives.”

The Greek Street shop opened three years ago and it’s one of a seven, after the Japanese Knife Company first started “in a carpark in Kilburn” in 1988. Patel first fell in love with Japanese knives after a visit to the country: “I got stuck in Japan for ten years, as an apprentice blacksmith, studying with a knife master there.” Much of what they sell is custom made by their 42 blacksmiths in Japan, says Patel, proudly: “We’re the largest provider of western-style kitchen knives in the world today.”

*

The original of now-global Soho House is on Greek Street, but the insider’s choice is arguably a little further up the street; the Union Club is marked just with a subtle letter “U” on the front. You need to know it’s there as you wouldn’t be able to tell by walking past – Shrimplin points out clubs right and left as we wander through Soho, behind there, upstairs here, downstairs here – and you need to be a member to get in.

It may feel a bit exclusive, but you don’t have to stick around in Soho for long before someone will invite you, telling you why their club is the best one. Shrimplin likes the House of St Barnabas for its amazing garden (charmingly, the doorbell is a literal bell on a rope), and Alastair Choat describes the Union Club as unlike anywhere else: “Peter Cross started it with his partner Carolyn Dawson, she’s the chef and she’s very good. Everything on the walls in there is stuff Peter’s found and put up himself. It’s a very individual place.”

Simo, Milroys

And then, of course, there’s Trisha’s – the unmarked blue door that opens onto a fluorescent-lit hallway that may put you off proceeding even if you’re sure you’re in the right place. But keep walking down and you’ll find yourself into a slice of old Soho so perfect that it shouldn’t quite exist. You technically need a membership, but the details around this are vague. I first went to Trisha’s, so called for its proprietor Trisha Bergonzi (formally it’s the New Evaristo, sometimes The Hideout), on an otherwise unremarkable night in January a couple of years back with a man whose name escapes me. The light was red and the tablecloths checked green, a nod to the bar’s former life as a gambling den. There were no windows and the walls were covered in photos of Sinatra, Bogart, boxers, footballers and regulars, with an out-of-place disco ball providing some questionable sparkle. I asked the barman for “red wine” and he reached for a bottle without any further questions – when I came back for another round he filled me up to the top as a “recycling bonus” for using the same glass twice. The cheap plonk was unremarkable but you bet I was charmed.

What I remember most from that night isn’t how the cigarette smoke drifted in from the airing shaft in the back which technically counted as smoking outside, or how much the 75-year-old bar looked like somewhere the mafia might have met – it was how the people in Trisha’s looked so different from what I was used to seeing in Soho. They weren’t trendy or young in the way you might associate with the area, but just regular people of all ages, shapes and sizes. In the corner was a woman singing Parisian jazz, the kind of music you’d expect in a place like this, and she had tight black curls and a tight green dress. On her record cover, it said Florence Joelle: Life is beautiful if you let it.

It was one of those nights on Greek Street – possibly the last great, lovably ‘shit’ street in Soho – and life was indeed beautiful. Nothing stays the same for long, but luckily most of the buildings in Soho are owned by entities (Soho Estates, Shaftesbury PLC, and the Crown Estate) who more or less consider it in everyone’s interest to work to preserve the area’s unique character. “It’s really tough to be a business owner in Soho, but if you immerse yourself in the community then you will do well and you will last a lifetime here,” says Martyn Simpson. “Soho is one of the last living communities in London that’s this tight. If you’re sexist, racist or homophobic you won’t feel at home here.”

Immersing yourself in Soho’s bold spirit isn’t for everyone, as it’s a gritty, sometimes uncomfortable, pleasure: “This place will eat you alive if you want it to,” Simpson adds. If we are lucky, and if we take care to protect it, Soho and Greek Street will stay beautiful, and delightfully shit, for a while longer.

Follow Jessica Furseth on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.