Using the internet to become your own doctor

- Text by Emily Reynolds

You can find pretty much anything in the world on the internet, along with similar minded people out there waiting for us all. From Facebook groups celebrating some of the most bizarre facets of our characters, to international Twitter campaigns that can fuel revolutions, it’s impossible to truly measure the power of the internet to bring people with shared experiences together.

The reality of living out our lives online, and the virtual communities that are built around them, is a topic that artist Lucy Beech has been keen to explore, particularly when it comes to looking at the way women deal with illness. Because when doctors and modern medicine tell you there is nothing wrong with you, the internet provides the perfect place to prove otherwise.

“We build a view of our lived bodily experience through a number of lenses,” she tells me. She points to the experience of female Morgellons sufferers, a group she worked with while making her new film, Pharmakon. Morgellons, a skin condition that is widely considered to be a delusional disorder, is largely self-diagnosed and, therefore, often neglected or maligned by traditional medical communities.

Online, communities of women with the disease have thrived on forums and social media, discussing their illness and coming to terms with it, supporting one another and providing advice. Beech describes this process of self diagnosis (“patient forums, doctor’s guidance sites, symptom archives, YouTube, advocacy websites…”) as collaborative process – particularly for women. Parallels can also be found in the mental health community, with blogs, articles and discussions flourishing, away from a healthcare system that can fail to provide adequate support, both psychological and physically.

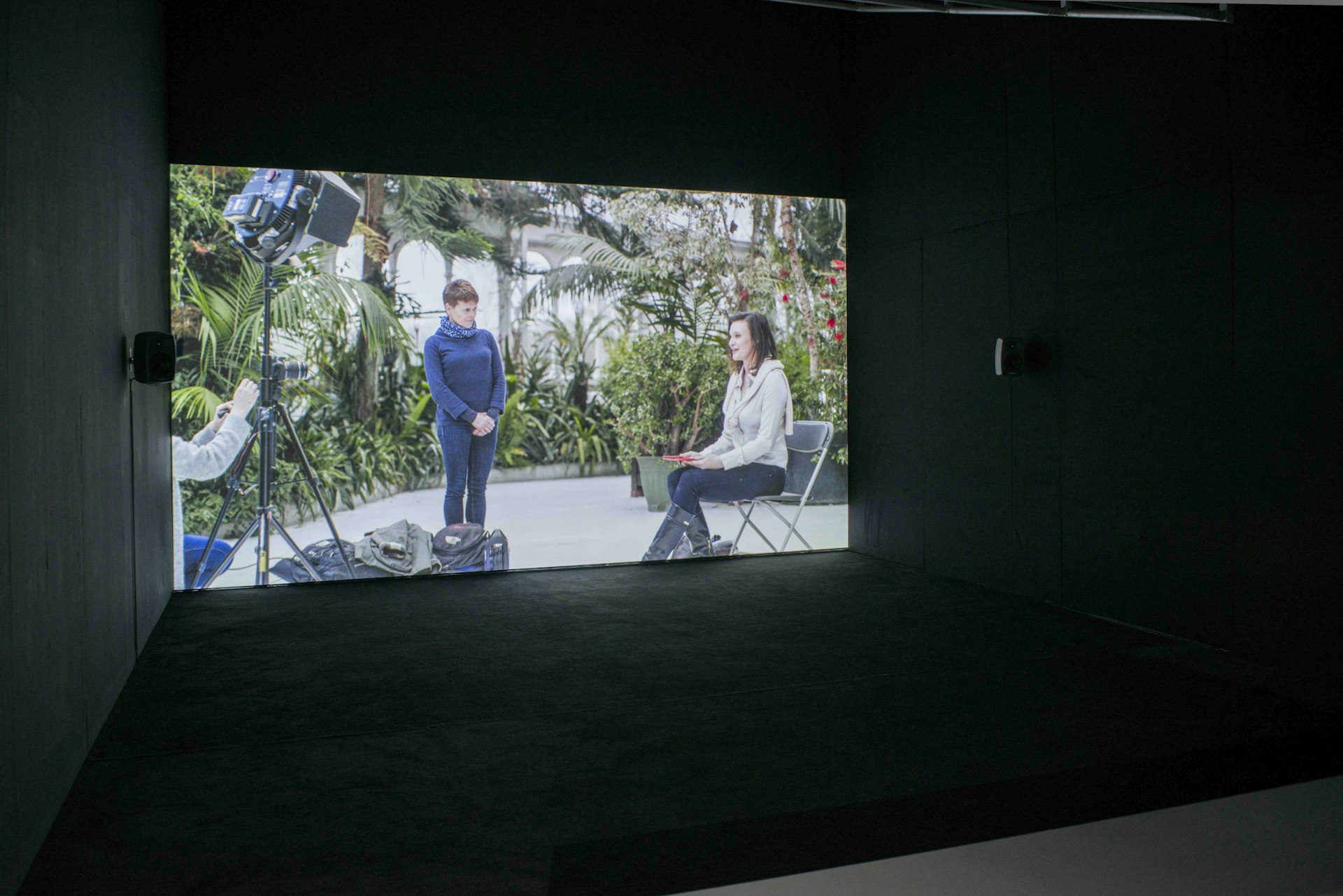

Pharmakon is Beech’s attempt to explore these issues. The film details the experience of a security guard who is “increasingly drawn into a world of bodily self-examination, hypochondria and anxiety”. Whether the security guard is accurate in her self-diagnosis, or dangerously finding a community that will encourage her own hypochondria, is not explored. (Modern medicine is not an exact science, but an ever changing art. Misdiagnoses do happen. And, psychological issues can also severely impact physical health.) Rather than addressing these issues, Pharmakon explores how our very real health anxieties can be both “alleviated and monetised” by big business.

“The screenplay itself is developed from interviews with clinicians working in the field of delusional infestation, advocacy websites, therapy groups, consciousness raising events and product launches for new alternative products and ‘cures’,” says Beech.

Diagnosis is a shared experience – both online and via a more traditional doctor patient relationship. But the way we navigate that experience is also inevitably influenced by capitalism, Beech says. Big business can help here – think of pharmaceutical companies providing anti-depressants, for example – but they can also capitalise on our pain. Self diagnosis can seem like a practical, and sometimes radical, antidote to this.

And online, away from stricter social definitions of ‘sickness’ and ‘health’, which are often reliant on a person’s ability to work and ‘be productive’, our experiences of sickness are more nebulous. We might have symptoms that are less common or are misunderstood, or we may relate emotionally in a manner that traditional medicine doesn’t cater to. This can be particularly pressing with diseases that are viewed as psychosomatic, like Morgellons.

These experiences may not be explicable or relatable within strict diagnostic definitions, and may exist “in the gap between an expectation of a disease and how it actually manifests”. This gap is where spaces of exploitation can emerge, with sufferers unsure how to deal with their symptoms, making them susceptible to manipulation from pharmaceutical companies and hospitals.

“My research for this film focused on certain diseases and conditions that fall out of mainstream biomedicine. Wellbeing is viewed in holistic terms in the interest of the ever expanding field of emotional capitalism, yet on the flip side people are quietly encouraged to maintain a very narrow view of illness.”

By engaging in online communities, we can escape what may feel like strict and limiting diagnoses from doctors, and perform self-care, both for ourselves and for those in our self-made networks. It is within these communities that we can redefine our experiences of illness – and find the radical potential in doing so.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.