A tribute to the incredible visual legacy of Frida Kahlo

- Text by Katie Goh

When you close your eyes and think “Frida Kahlo” what pops into your head? Chances are it’ll either be one of her numerous self-portraits, or a tote bag. You can buy the iconic Mexican artist’s face on nearly anything – from socks and pillows to t-shirts. She has even become a (controversially white-washed) Snapchat filter, a Halloween costume, and a Barbie.

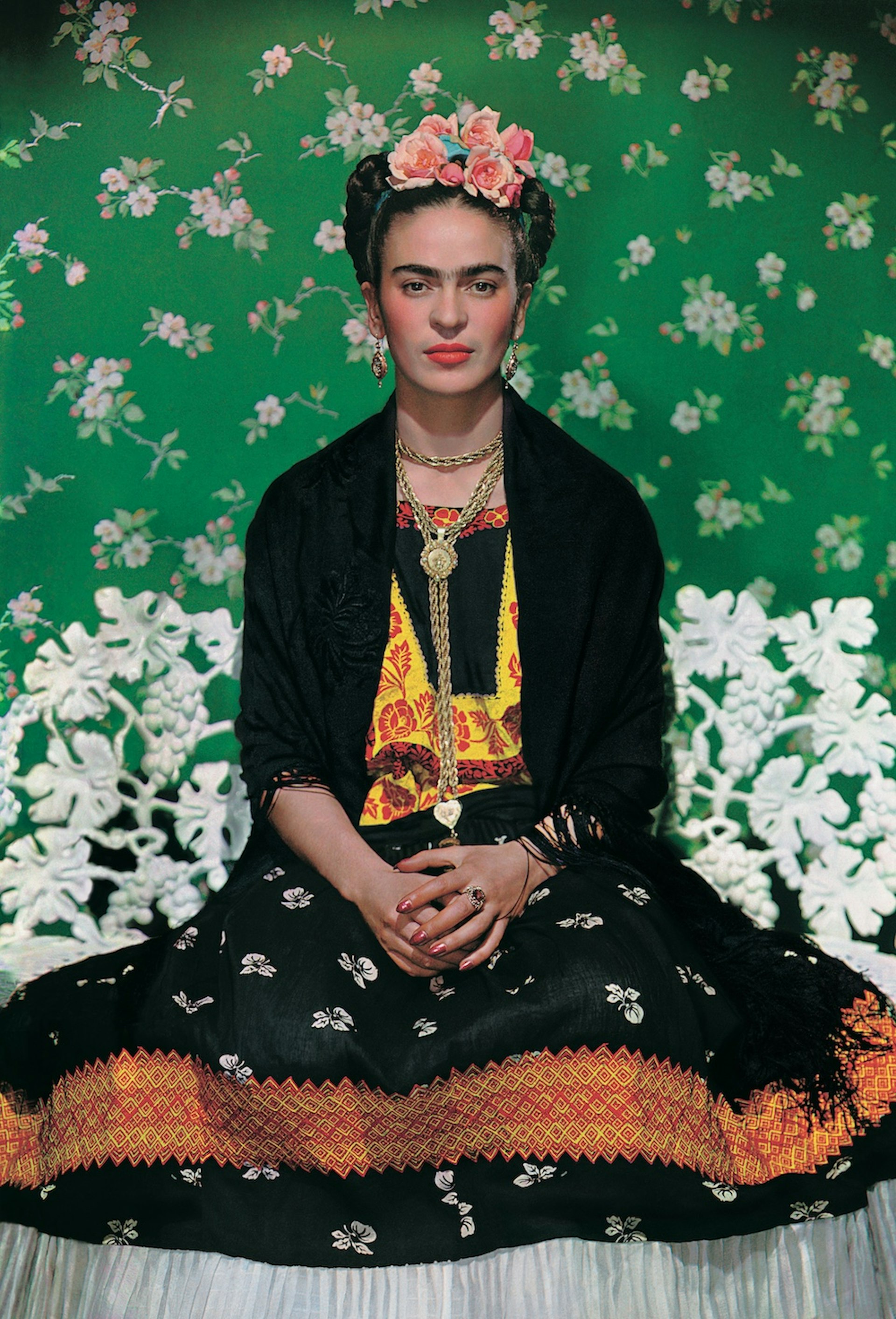

Her legacy has become something of a joke, given how much Kahlo knew about image – particularly her own image. As a young woman working in the male-dominated Mexican art scene, Kahlo was always aware of how she appeared.

This incredible sense of style which is being celebrated – along with her art – at a new exhibition opening this weekend at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. The show, titled Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up, features a selection of the artist’s clothing and personal belongings. It’s the first time the collection has been on public display outside of Mexico.

Self Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States of America, 1932

Kahlo’s life, style and art were shaped forever at the age of 18, when she became disabled in a road accident which saw a metal handrail pierce both her pelvis and her uterus. The realities of Kahlo’s life – her gender and sexuality, her infertility after the accident, her Mexican heritage – are all explored through her artwork, primarily in self-portraits.

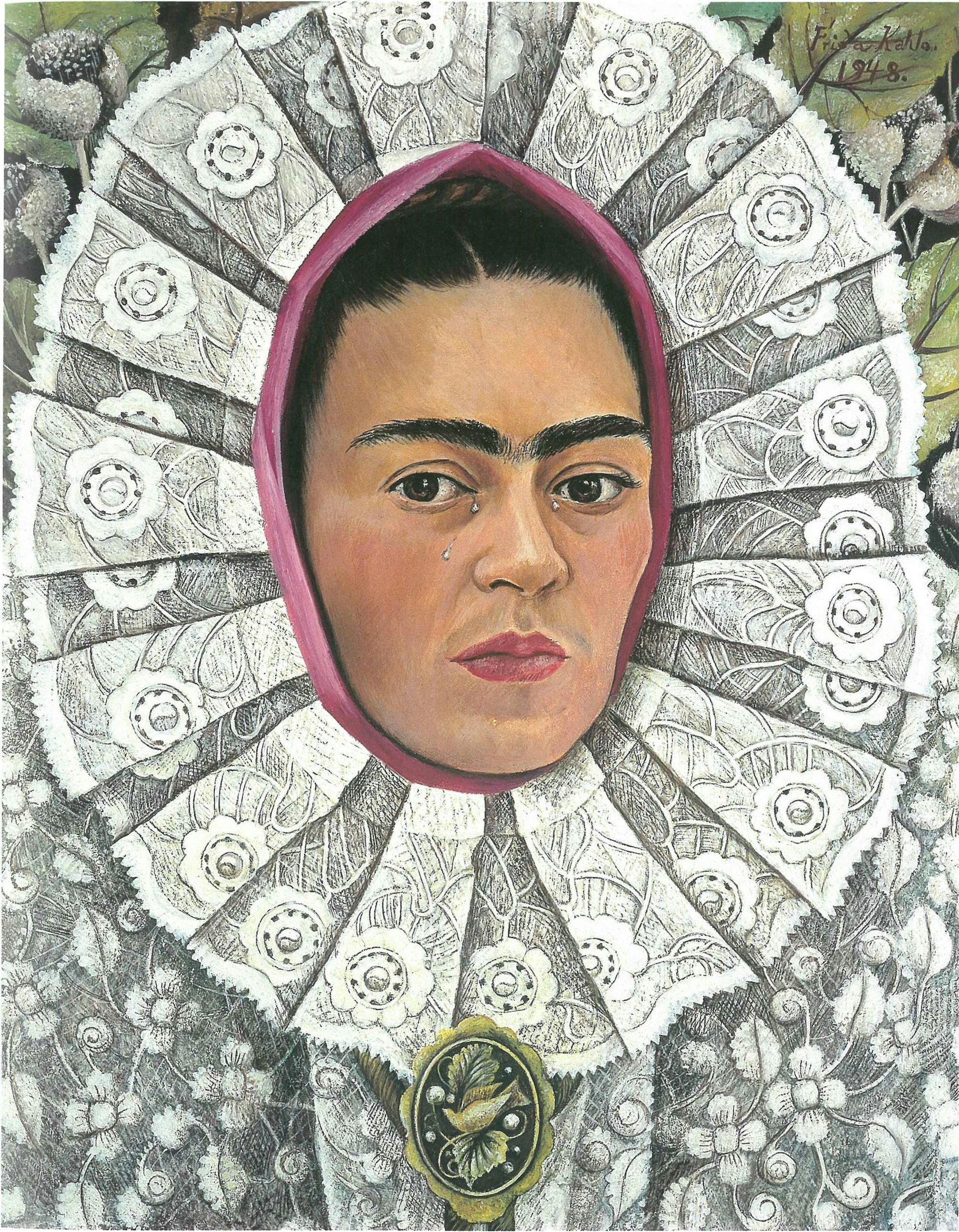

In her art, Kahlo doesn’t just represent herself; she embellishes herself. Sometimes she has wings, sometimes she’s surrounded by plants and panthers. She explores her disability in paintings like ‘The Broken Column’, in which she is kept upright by a metal pole, and ‘The Wounded Deer’, in which her head is transplanted onto a deer struck with arrows. Sometimes she’s flying, or dreaming, or a baby. In 1953, when Kahlo’s leg was amputated, she wrote in her diary: “Feet? What do I want them for, when I have wings to fly.” Kahlo understood that in art, the possibilities are endless.

Prosthetic leg with leather boot. Appliquéd silk with embroidered Chinese motifs. Photograph Javier Hinojosa. Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums

In her personal life, Kahlo had a similar philosophy. Her body was as much a work of art as any canvas and like her paintings, she embellished it. In a famous family portrait, she poses in a three-piece suit, hair slicked back with one hand in her pocket. She’s assertive, making direct eye contact with the camera. In her paintings, she similarly played with perceptions of gender, such as her 1940 ‘Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair’ in which she’s styled in a similar fashion to the family portrait.

Clothing was a means of playing with form. Kahlo loved shopping and often commissioned specifically tailored clothes. Long, bright skirts have become ubiquitous with her image, yet while they’ve come to define Kahlo, they also conceal her disability. And when she did reveal her prosthetic leg, she really wanted you to see it. Painting it crimson – a nod to her communist allegiances – and decorating it with a fierce dragon, Kahlo took her disability, something that in the early twentieth-century she would have been made to feel ashamed of, and turned it into something beautiful and eye-catching that you couldn’t keep your eyes off.

Frida Kahlo in blue satin blouse, 1939, photograph by Nickolas Muray © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Similarly, Kahlo adorned her face with bright red lipstick and blusher – the feminine juxtaposed with her masculine facial hair. While male artists like Andy Warhol and Vincent van Gogh also readily used images of themselves in their art, Kahlo truly understood the power of self-representation because, as a woman, she used cosmetics and clothing as smoke and mirrors every single day to present an image of herself to the world.

Asked why she paints so many self-portraits, Kahlo remarked, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone.” In her paintings, she’s always a lonely figure, surrounded by the images of her psyche but typically the only person in the frame. Often left alone because of her gender and disability, Kahlo decided to represent her own life on her own terms. She took her prosthetic leg, an instrument of torture that caused her agony, and decorated it in bright hues for her own and the viewer’s pleasure. Simultaneously performance and reality, Kahlo’s life and body were her greatest canvas. It’s no wonder we can’t take our eyes off her.

Self-Portrait, Frida Kahlo, 1948 © Private Collection

Cotton huipil with machine-embroidered chain stitch; printed cotton skirt with embroidery and holán. Ensemble from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Photograph Javier Hinojosa. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

Frida Kahlo, c. 1926. Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

Frida on the bench, 1939, photograph by Nickolas Muray © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

Self-portrait, Frida Kahlo, 1941 © The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Collection

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is running at the Victoria and Albert Museum from 16 June – 14 November 2018. The exhibition is sponsored by Grosvenor Britain & Ireland.

Follow Katie Goh on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.