Inside the weird, shady world of click farms

- Text by Isaac Muk

- Photography by Jack Latham

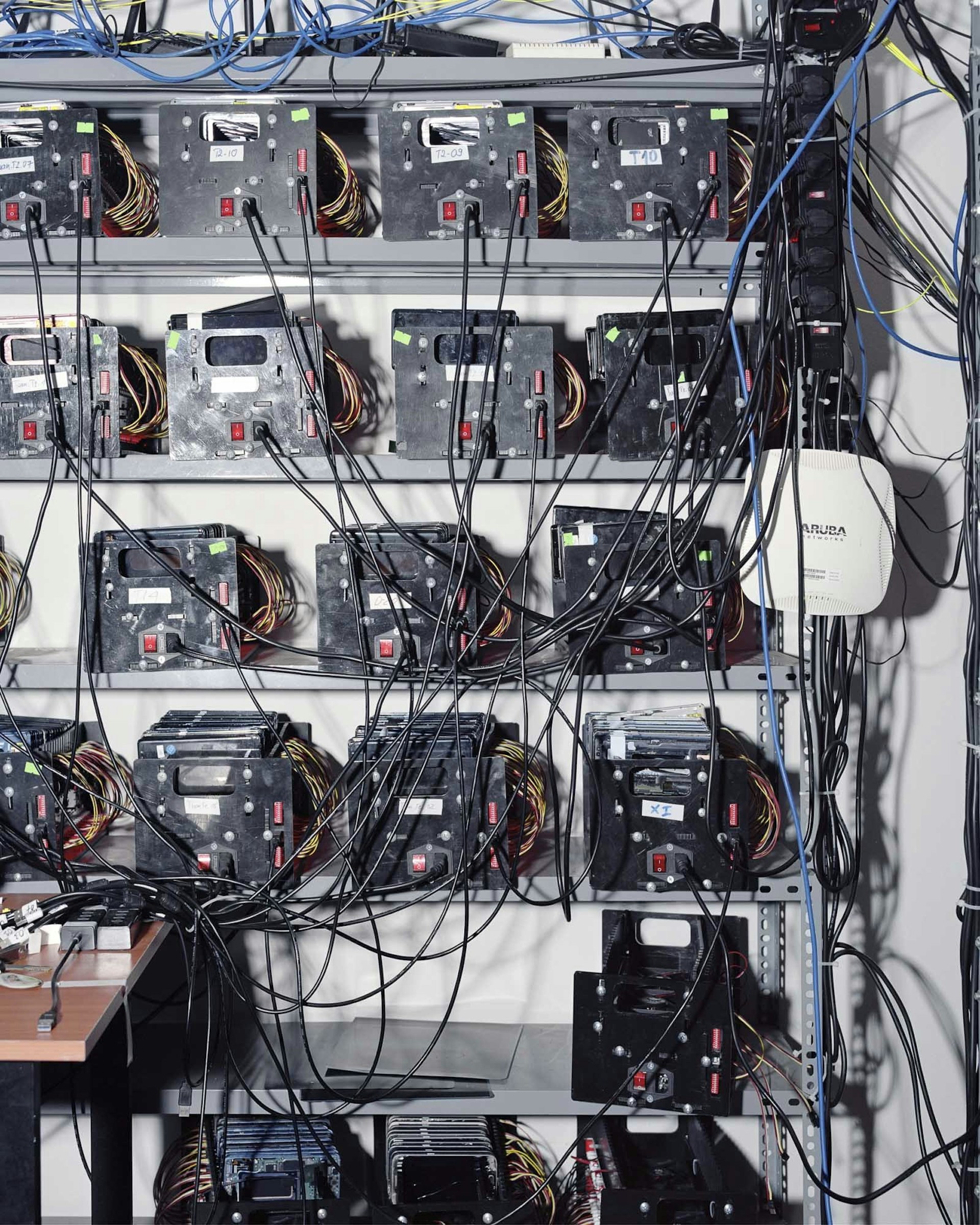

Early in 2023, photographer Jack Latham was in Hong Kong, when he received instructions to visit a nondescript hotel among the city’s densely packed skyscrapers. Over the past four years, he had been searching for access to a click farm – shadowy operations that use large numbers of electronic devices to boost engagement online and manipulate algorithms – and after connecting with some people on hacker forums, he was now visiting one for the first time. Taking the elevator to the top floor, he was shown into a small room where hundreds of smartphones lined the walls, all connected to computers via a dense web of cables.

Eight people worked on the phones, sending thousands of likes and follows to content that they had been paid to promote. “It was quite strange, it almost felt like an office – I felt like I was at a young tech startup, I don’t think anybody there was older than 25, and they broke down the software and how it all works and what you can do,” Latham recalls. “These phones are connected to a main computer and when a client pops up, whether it’s Instagram, Facebook or TikTok, they then enter someone’s profile, which appears on every single phone simultaneously, and you press follow or like.”

The fast engagement artificially inflates the popularity of their posts, as well as tricking algorithms into boosting content more, giving clients the opportunity to go viral quickly. “Each phone is a different account, and each can change its IP address 20 times [a day],” he continues. “Each phone is technically 20 different phones, so you can see how it scales up.”

After that first visit, Latham sought out other click farms across Vietnam and Hong Kong, photographing what he found inside and even purchasing his own farm, which he keeps stowed in the living room of his London apartment. Those shots he took during his travels, showing the endless telephones laid out neatly in rows, are presented in his new photobook Beggar’s Honey, alongside obscured, surreal pictures he manipulated from people who reached out to him asking for boosts to their content.

“The way [the book works] is that you flick through foldouts that look like phones, and you have nothing but content that people have asked me to like on social media as a click farmer,” he explains, before detailing examples of the media he was asked to boost. “There was something about immigrants, other things like how to spot a fake Rolex, there’s lots of nudity, military propaganda and videos of armies, conspiracy videos about the Twin Towers and a conspiracy video about the vaccine.”

Within a landscape of misinformation and disinformation, it’s easy to see how click farms could be used dangerously. “It’s also been used for nefarious reasons, [a member of] the BJP Party in India was found to have been buying fake comments on social media,” he alleges. “I don’t think a lot of people share things on a big scale intentionally to fool people, but people just get fooled by it, and I think content is thrown at you so quickly these days that it’s almost impossible to take notes of what you’re seeing.”

Latham even manipulated the announcement of his book, which proved to be an effective way to engage his followers. “When we initially launched the book, the only time I used it is to promote my initial [Instagram] post,” he says. “So, within 30 minutes, I had 8,000 likes on the post – I could see in real time that this thing was growing and growing. When I did a lecture one of the people in the audience said, ‘I saw you post it and I bought the book straight away because I thought this book looks incredibly popular, so I should probably buy it.’”

The pictures form a surreal, discomforting look behind the curtain of the endless stream of content that now dominates our consumption of media. Latham’s work helps unravel and interrogate the authenticity of what we view through our screens, while also raising questions about what success means in today’s hyper-online, personal branding driven world. “I can certainly understand the proclivity for one thing to look popular – say you’re a local bookshop or bike repair shop and you make an Instagram account and it has zero followers and all of a sudden it doesn’t have the same kind of authority as something that maybe has 5,000,” he says. “So I think [using click farms] is incredibly common.

“There’s this need to appear more popular than you are as a form of validation and there’s certainly people in my industry I know who have purchased followers,” he continues. “I think we’re allowing the metrics of social media to infiltrate our self worth in a way that I think is quite fascinating.”

Beggar’s Honey by Jack Latham is published by Here Press.

Follow Isaac on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.