Women in Skateboarding

- Text by Tetsuhiko Endo

- Illustrations by Matthew Green

“Women who prefer exercise and liberty, who revel in the cool sea breeze and love to feel the fresh mountain air fanning their cheeks, who are afraid neither of a little fatigue nor of a little exertion, are the better, the truer, and the healthier, and can yet remain essentially feminine in their thoughts and manners.” – 1894 Lady Violet Greville in Ladies in the Field Sketches of Sport

One afternoon in 1997 twelve-year-old Lucy Adams was leaving swimming practice in Horsham, England, when she noticed a large construction fence had gone up in the vacant lot behind the pool. She wandered over and peered through a small hole in the boards. On the other side a group of men dressed in long T-shirts and baggy jeans were building something that she would later describe as “fantastic”. With heavy iron bars, scaffolding and large, smooth strips of wood they fashioned swooping curves, elegant arcs, gentle waves and precipitous drops into something that looked like a cross between an obstacle course and a post-modern sculpture. She returned as often as she could and watched as the ramps and transitions took shape and the men began to ride them with their skateboards.

One evening before the park had officially opened she went over, roller skates in hand, and approached the men. “Can I have a go on my skates?” she asked. They laughed and told her she needed a skateboard. “So I went home and told my dad, ‘These are shit now, we need a skateboard,’” she says. Adams has gone on to become one of Britain’s best skaters, but her wider relationship to the skate industry remains very similar to those early days of peeking through the fence. Skateboarding may not be against women, but it’s certainly a consolidated boys club.

There are few reliable statistics regarding the number of skateboarders in the world, much less the number of female skateboarders. The US boasts over 12 million riders, with the number of women in this group ranging from twenty-five per cent to nine per cent, depending on the source. If, for the sake of argument, we take the higher estimate, the number of women skateboarding is roughly consistent with the number of women participating in both surfing and snowboarding. However, compared to its sister sports, female skateboarders are still a silent, invisible minority and skating in the wider public consciousness remains a ‘guy’s sport’.

Adams didn’t realise it at the time, but by squeezing through the fence and daring to “ask for a go” she was, like so many girls before her, stepping onto the frontlines of a bitter, and contentious gender conflict that has quietly raged in the dark recesses of Western society’s subconscious for over 250 years. It’s a struggle not over land or money, but what the sociologist Michael Messner calls the “contested ideological territory” of the female body. At stake is the very definition of what it means to be a woman and how you can legitimately use your body.

“Athletic meetings… always attract a large number of women, perhaps it is the gay colours of the runners, perhaps it is their youth and splendid physical condition, whatever the reason, they come in their thousands and bring brightness and colour to the scene even if their appreciation is not always particularly intelligent.” – The Times, 1919

The notion of ‘guy’s sports’ and ‘girl’s sports’ is completely socially constructed; the ill-begotten child of the specific time period and societies in which sporting culture originated, namely Britain and the United States during the Industrial Revolution. Although physical competitions existed before the socio-economic upheavals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it took capital, a sedentary leisure class, and the then revolutionary idea of ‘leisure time’ to turn games into what we know as sports today. As machines streamlined production and the work day became shorter and less physical, middle and upper class men who spent a lot of time sitting behind desks found that exercise was a good way to blow off steam. Tennis, football, American football, rugby, basketball, athletics, swimming and many other sports were refined and popularised as leisure-time activities during this period.

But while the Industrial Revolution meant physical liberation for well-to-do men, it meant the opposite for their wives and daughters. The prevailing medical dogmas of the time dictated that the ‘nature of women’ was determined by a fixed degree of energy for all their endeavours (mental, physical, emotional, etc.). This theory meshed well with the bourgeois Victorian ideal of the idle, porcelain-doll woman whose role in society was to look good, be the moral heart of the family, show off her husband’s wealth through the purchase of expensive items and make babies. The last point is paramount because it has often been a reason, overt or underlying, to exclude women from sports.

In Sporting Females, an illuminating book on the history and sociology of women’s sports, Jennifer Hargreaves quotes the chairman of the British Medical Association who, in 1887, emphatically stated that for the “‘progressive improvement of the human race’, women should be denied education and other activities which would cause constitutional overstrain and inability to produce healthy offspring.” The Eugenicists even got in on the act claiming that sports could cause hormonal imbalances in women and hockey in particular (the bête noire of the anti-female sports movements) would disable young women from being able to breastfeed. And so, from their earliest incarnations, sports were codified in such a way as to explicitly exclude women.

“Woman’s anatomical characteristics are analogous with man’s but her physiological predisposition demands less vigorous treatment. The law of beauty is based purely on the conception of life and must not be abused. The rounded forms of woman must not be transformed into angularity or nodosity such as in man.” – Pehr Henrik Ling, Inventor of Swedish Gymnastics, 1939

“When sidewalk surfing hit big in the 1960s, both males and females skated,” says Michael Brooke, publisher of Concrete Wave magazine. “The population skewed more towards males but, I mean, Pattie McGee doing a handstand on her board made the cover of Life magazine in 1965 – that’s one of most iconic skateboarding images of all time.”

Women stayed on the scene as an important minority for as long as the skateboard industry focused the action on skateparks and remained broad in its definition of the sport: from vert and park, to slalom, freestyle and street, girls and young women got involved. However, the late 1970s saw a mass extinction of parks and a narrowing of the industry as well as the fusion of skate and punk rock culture that, Brooke speculates, pushed skating in a more male-oriented direction. “I’m not suggesting women didn’t follow punk rock – they did. But I think it made the industry very testosterone driven. All of a sudden, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, it’s men listening to punk rock and riding on skateboards. All this changed the image, it got a lot more aggressive, a lot more underground.”

The 1990s were boom times for the skateboarding industry, but the companies increased their market shares through a somewhat Faustian bargain: by narrowly focusing on selling street skating to a young, male demographic. “They bet the farm on kids doing rail slides and forty-stair ollies,” says Brookes. “Once the industry decided it was going after one thing, it started checking these boxes: males – check; males under 18 – check. And as it hit each check point it was reducing the population it was going to appeal to.”

Such a narrow demographic is a big deterrent, especially for older women says Brooke: “If you ask a thirty-five-year-old woman if she is comfortable hanging out with thirteen-year-old boys, the answer is no.” Additionally, a hard focus on selling soft goods to teenage boys meant that women were not simply ignored, their image was co-opted and turned from that of active participants like McGee, into passive, hypersexualised groupies, like the scantily clad model in the ‘Rosa’ adverts run by skateboard company Shorty’s throughout the 1990s. Whatever Rosa’s skills may have included, skateboarding was certainly not one of them.

“There is a well-known Girls’ College which makes pre-eminently for the cult of mannishness. And here are seen, absorbed in fierce contest during the exhausting heat of summer afternoons, grim-visaged maidens of sinewy build, hard of touch and set as working women in the ’40s, some with brawny throats, square shoulders and stern loins that would do credit to a prize ring. All of which masculine developments are stigmata of abnormal sex-transformation…” – A criticism of Dartford College, in London, which had an early physical education programme for women, 1920

As educational opportunities increased for women in the nineteenth century, so too did their sporting opportunities. By the beginning of the twentieth century, most doctors were in favour of exercise for women, but the types of exercises considered appropriate were limited, at best. The most famous of the early ‘women’s sports’ was something called Swedish Gymnastics, a sort of proto-aerobics that featured a highly regimented combination of calisthenics, stretching and physical therapy whose aim was both exercise and subtle nationalist indoctrination. Other sports followed like tennis, hockey and netball, a non-contact version of basketball that is still played exclusively by women.

Note the pattern: ‘women’s sports’ tended to be ones that reinforced wider societal stereotypes about how women should or could behave. Many, like dance or gymnastics, were obsessed with rigid bodily control. Sports that allowed freer movements, or some other transgression of the Victorian feminine ideal, like overt aggression, were roundly criticised and the women involved in them stigmatised. When the ‘safety bicycle’ became popular in the 1880s and women began to ride them in their specially designed undergarments – or ‘bloomers’ – an entire world of bodily and spatial freedom opened up to them. The critics also came out of the floorboards. “Cycling… was claimed to be an indolent and indecent activity which tended to destroy the sweet simplicity of a girl’s nature and which might cause her to fall into the arms of a strange man!” Hargreaves writes with ironic relish. “The worst fear was that cycling might even transport a girl to prostitution.”

“Modern sports is a cultural system created by men,” says Dr. Uta Balbier, who teaches a class on the history of sports at Kings College in London. “It has a lot to do with urbanisation, but it also has to do with mechanisation, bureaucratisation – keeping records was a big part of shaping the modern sports system – and all this was done by men and all women could do after this was try to fit into the system.”

Because sports were and continue to be defined by men, they are shot through with certain stereotypes that are internalised by both sexes. “The major stereotype is still this ‘masculinisation’ of women who play sports and that this masculanisation leads directly into ‘lesbianism,’” says Balbier. “You cannot be a ‘beautiful’ wrestler or even a ‘beautiful’ boxer because even though we try to get out of our gender perspectives, we can’t… We still see certain sports that don’t fulfill our own perceptions or images of femininity. And that is why many people really don’t want to watch women box, for example. It takes such a long time to establish new images.”

“Hers is all the joy of motion, not to be under-estimated, and the long days in the open air; all the joy of adventure and change. Hers is the delightful sense of independence and power.” – Lady Violet Greville on the joys of bicycling

Away from Western skate culture, the image of the female skateboarder is being re-built from the ground up. The country that arguably has the highest percentage of female skateboarders in the world is Afghanistan, where girls are neither allowed to ride bikes or fly kites. Of course, skateboarding is only about three years old in Kabul. It was introduced by a pair of itinerant Aussies who went on to found NGO Skateistan. “We’ve always made a point of not trying to import any of the cultural elements of skating,” says Rhianon Bader, one of Skateistan’s mix of local and international instructors. She grew up riding the streets and parks of Calgary, Canada, in the late 1990s and early 2000s where come-ons and sexist comments from the mostly male skating population were par for the course. “Because skating was totally new in Afghanistan, no one had any preconceptions about it,” she says. “It was seen not as a new sport that might be dangerous or have certain gender taboos associated with it, but just a game, or a toy.”

This clean cultural slate has seen a nearly equal split between the roughly 400 boys and girls who participate in Skateistan’s programmes. The main difference is that the boys are lining up around the block to skate while Skateistan has invested a lot of effort into recruiting girls. One of the most important tactics, according to Bader, was establishing all-girl skating hours when young women can have the city’s one skatepark entirely to themselves. “I think it’s universal that when girls are adolescents or teenagers they get intimidated when boys watch them play sports,” she says. “So once we made that space where it was comfortable for girls just to skate, we really enforced it and it worked really well. I think a lot of the attraction to the sport just comes down to girls seeing other girls doing something.”

The Longboard Girls Crew, based in Spain and recent media darlings the world over, embraces the same ethos of creating a pressure-free space for females to skate with each other. By choosing longboarding, which, although not a new discipline, is in the midst of a mini-renaissance, they have found a niche that has not yet strictly defined its gender image. At least not as strictly as street and vert. With an active blog, a large team, and links all over the world, they are a breath of fresh air. However, without significant industry backing, or indeed a significant industry to back them, it remains to be seen if they are the start of a movement, or simply a flash in the pan.

Brookes, for one, sees hope in the latent longboard industry. “Skateboarding is too good to be controlled by a handful of people who think it’s just a handful of rails and ledges. It’s like saying soccer can only be played by people of European extraction, golf is only for white people, or bike riding is only for guys. The bike industry is worth 61 billion dollars a year, and there are so many different genres. Skateboarding used to be like that and it can still be like that.”

“Your girls play like gentlemen, and behave like ladies.” – ‘Compliment’ paid to a headmistress about her cricket team in 1891

The task of establishing new images in the Western world – where skateboarding has grown up with men at the helm – has been taken up by a loose group of female skateboarders who are now in their thirties. Though some of the best in the world, their careers have often played out on the margins of a disinterested industry. They include Adams, fellow Brit Jenna Selby, Californians Mimi Knoop and Cara-Beth Burnside, and Lisa Whitaker to name a handful. They face an uphill battle. Aside from occasional, if very significant victories, like Burnside and Knoop’s Action Sports Alliance gaining equal prize money for men and women in X Games events, many of their achievements in growing their sport have taken place under their own initiatives without much help from the larger skateboard companies.

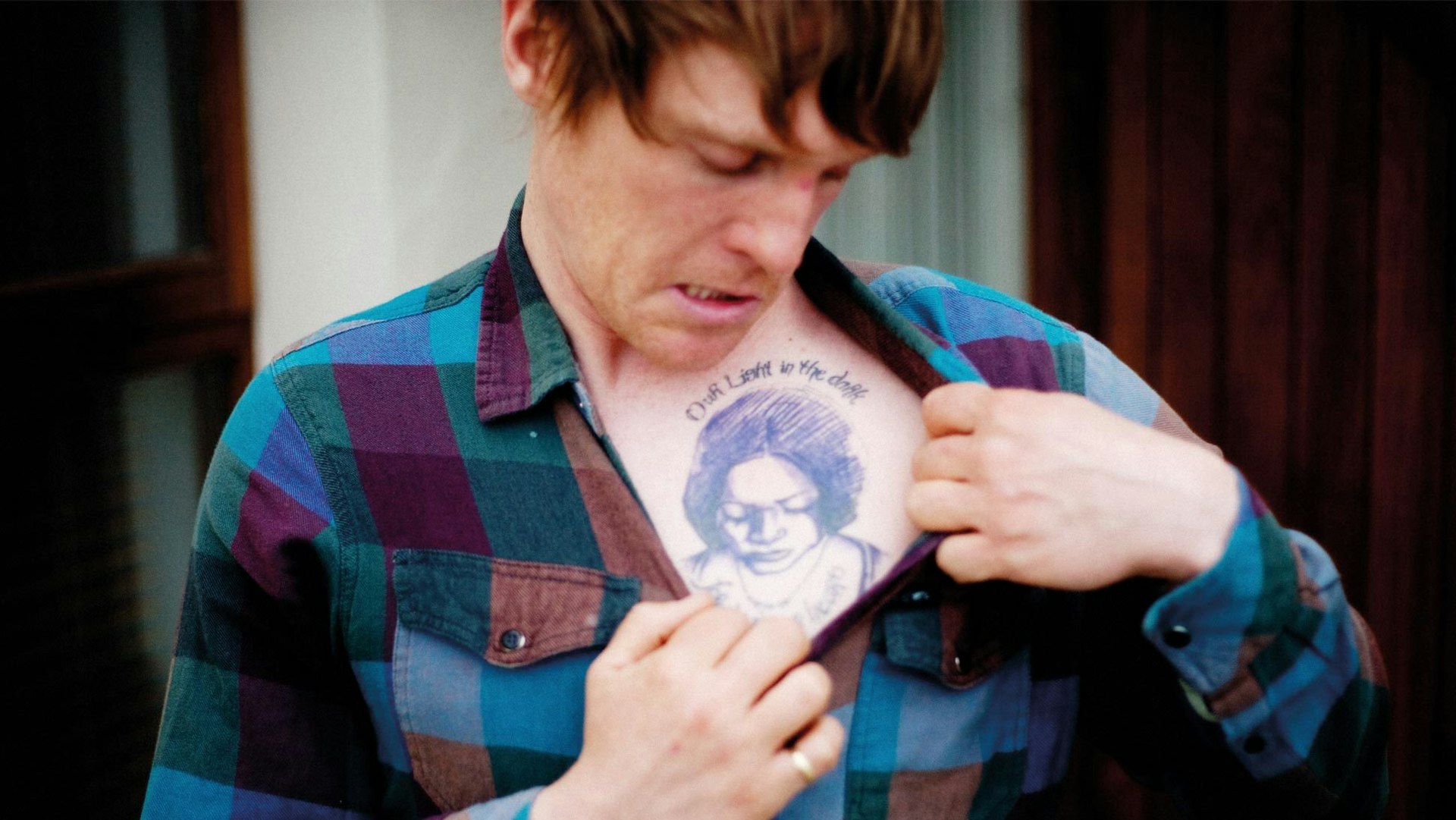

Whitaker runs a website called the Girls Skate Network which is a hub for anyone who wants to post photos and videos of female skaters. It is home to an active forum and regular interviews with up-and-coming riders. Selby hosts all-girl skate jams in England, with the help of female-focused brands like Nikita, and also founded Rogue – an all-female skate company that doesn’t bend to stereotype. She travels the world making women-centric skate films, including 2009’s As If, And What?, the first all-female skate video in Europe, and is currently working on her next. Ironically, these women and the younger generation of skaters they are nurturing, may constitute the only authentic counterculture that still exists in this multi-billion dollar industry.

But growing that community can be tough. “One thing we noticed in the UK scene, especially when I was younger, is that there were younger girls with amazing skills who would hit their teenage years and sort of disappear due to outside pressures like what their friends were doing and what magazines were telling them to do,” says Selby.

The trend she touches on is common in many female sports where girls drop out as their bodies mature and the role models available to them change from energetic girls to sexy women. Skateboarding suffers in particular because it is inherently threatening to a rider’s body, which is in turn threatening to the still prevalent Victorian notion that the female body is delicate and must always be protected. Remember that Victorians worried what horse riding would do to women’s nether regions; imagine how they would react to the danger of a young woman smashing her crotch onto a rail.

Some industry players have tried to combine the two images in order to attract women to the sport, but the result is problematic. “I’ve noticed recently that some magazines are more interested in the girls that fit a certain profile: one that looks ‘right’ rather than one that has a certain skill level,” says Selby. “That’s something we are trying to avoid because I know surfing has gone down that route… It’s not all media. But it’s almost like some of them are trying to fit us into this box, you know, ‘This is what people want to see. In doing so, I think they are moving away from the core ethics that they perhaps started out with. I know everyone’s got a job to do and magazines to sell, but you need to remember your ideals as well.”

Adams is less circumspect when describing the ‘right look’. “It helps to wear short shorts, inappropriate shoes, and tight tops. It also helps to have long blonde hair,” she explains wryly, having never bowed to the pressure herself.

The marketing argument goes something like this: the only way to sell the sport is to show sexy, rough-and-tumble Lolita’s playing it.It’s not that we’re sexist, it’s what the public demands. “On the surface, the money making argument is legitimate,” says Dr. Kerrie Kauer, a sports and women’s studies scholar at the University of California, Long Beach. “But if you are trying to market surfing, for instance, to young female surfers, why not show young female surfers surfing, instead of lying down with boards on the beach? What they are doing is marketing women’s sports to young men in the eighteen-to-thirty-five age range… If you actually sell to people interested in sport you have a whole new market.”

One brand that is engaging with that market is Hoopla, an all-female skateboard company founded by Californians Cara-Beth Burnside and Mimi Knoop. “There are more girls skating than ever, but you might not know it because it’s so underground,” says Burnside. As one of America’s greatest competitive skaters and snowboarders she has perhaps been the most visible ambassador of women’s skating for the last twenty years. When Vans dropped her from their team in 2011 there was even talk of a boycott. According to her, if female participation, and more importantly visibility, is to increase, skating will need to appeal to parents first. “For me, a big part of getting and staying involved in skating was having supportive parents who never told me, ‘You’re a girl and you shouldn’t be doing that,’” she says.

Convincing other parents to think like hers has become one of Burnside’s professional goals. To this end she and Knoop use Hoopla to promote a female skating image that represents a happy middle ground between the Lolitas of the surfing world and the rugged hardiness often associated with skaters: neither overtly sexual, nor overtly masculine. “I want to show girls doing what they love and still looking like girls. On one end you don’t have to look like a guy, and on the other you don’t have to wear a really short skirt or your bikini just to get attention,” Burnside says. “I think if parents can see girls looking like normal girls doing their thing in cute little skater styles they will think their girls can do that too.”

To some degree, this solution seems to substitute one pigeonhole for another. I consider pointing out that the ‘normal girl’ is another stereotype, just like the ‘gnarly masculine girl’, and both are moulds to squish young women into. But as if pre-empting my question, Burnside insists she’s just being pragmatic. “That is the reality of being a girl skater,” she says, “you have to do things a certain way if you want the sport to grow. It’s the same with girl athletes everywhere – no one wants to see girls looking like dudes. You might not like it, but you’ll have to meet in the middle if you want to do something more with your career… and that goes for anything in our society. If a girl wants to do anything people can relate to her more if she just looks like a presentable girl.”

Not exactly what you would call ‘uplifting’. But then, real pragmatism rarely is. It is, to borrow a metaphor from Latin American liberation theory, about knowing you are in a cage, and taking small steps to increase the size of the cage. After all, you can’t break the bars until you have room to take a full swing. In the meantime Burnside and her small but growing vanguard keep expanding, inch by inch, because if they don’t, no one is going to do it for them. Through it all, Selby remains cautiously optimistic about the future: “Skateboarding is at a point right now where it can go one way or another and we are just trying to keep the importance on skill and personality, not on what a girl looks like or how she dresses.”