The courageous story of Westerly Windina has lessons for us all

- Text by Jamie Brisick

- Photography by Brodie Standen

Last November I boarded Thai Airways Flight 474 to Bangkok with my friend Westerly Windina, formerly Peter Drouyn. Westerly wore the sort of outfit Marilyn Monroe might have worn for a flight back in the fifties: black-and-white ballerina flats, white Capri pants, tangerine sweater. Her blonde hair was pinned into little curls. She applied a fresh coat of ruby red lipstick every five minutes. “Do I look alright?” she asked me for the fifteenth time. She was palpably nervous. In the three years I’d known her she’d spoken nonstop about her “completion”, i.e. gender reassignment surgery. Now it was less than seventy-two hours away.

I first met Westerly in August 2009 when I wrote a piece about her for The Surfer’s Journal. At the time I knew little about Westerly, but lots about Peter. Peter Drouyn was a surfing legend. Born in 1950, he spent his early years frolicking on the beaches of his hometown, Surfer’s Paradise, in Queensland, Australia. He rode his first wave on a balsa board at age eleven. He surfed his first contest a couple years later. At age fifteen, on the eve of the 1965 Australian Titles, he got badly beaten up by a trio of surfers and spent most of the night in hospital. The following morning he showed up to the contest with a bandage on his forehead and something like steam coming out of his nostrils. He blitzed his way to the final and won, setting forth a theme: throughout his long career, Peter would see himself as the perennial outsider. After a trail of victories in Australia he travelled to Hawaii and flourished in the big waves. He won the prestigious Makaha Invitational, came second in the Duke. While his contemporaries did walkovers and hang fives, Peter heaved up and down, back and forth, pioneering what the Aussies dubbed the ‘power style’. He could lose himself on a wave; apply every nerve, every cuticle. “It was a rebellion thing,” Westerly told me. “Peter powered. He had to get it out of himself. He’d punch the wave.”

In 1971, Peter enrolled in the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) and studied Stanislavski’s system – an approach in which actors draw upon personal emotions and memories, and immerse themselves fully in their characters. From this he developed “method surfing” – “you are one and the same, you become the ocean by degrees of concentration and relaxation, kind of a hypnotic state… I went out and just became the ocean.” In 1977, he invented the man-on-man competition format – still the benchmark today. In 1984, he challenged four-time world champion Mark Richards to a showdown. Dubbed ‘The Superchallenge’, it seemed less about determining the best surfer than showcasing Peter’s wild imagination. He took out campy advertisements in the surf mags: Peter clad in underwear, smeared with ketchup, posing Gladiator-style, with Muhammad Ali-like jibes slashed across the page. In 1985, he brought surfing to The People’s Republic of China.

Peter was a showman par excellence. But he never got the accolades he felt he deserved. Sad stories pepper the nineties. After a series of false starts he ended up destitute, living in caravan parks or with his parents. At a Masters contest in Fiji he got punched out for hitting on a fellow surfer’s wife. At an awards banquet in Australia he grabbed the mic and sputtered vitriol at all in attendance. He was booed and tomatoed off the stage.

In 2008, Peter appeared on Australian national television announcing that he was living as a woman. Her new name, she said, was Westerly Windina. Surf magazines and websites picked up the story. They cast Westerly as a social pariah, a laughing stock.

I was genuinely curious. I felt a certain kinship with Westerly. I grew up in California’s San Fernando Valley – disastrously uncool in the surf world. When I started surfing contests in the early eighties I found the scene to be cliquey and frat boy-ish, a far cry from the bohemian seventies. I competed on the ASP Pro Tour for five years, during which time I was rather put off by the narrow-mindedness of surfing’s elite. My antidote was reading. Literature embraced our inherent strangeness, made it all feel okay. I can remember the very sentences that inspired me to become a writer. Paul Theroux: “Writing is an education in the eyes of the public.” Henry Miller: “Develop an interest in life as you see it; the people, things, literature, music — the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls and interesting people. Forget yourself.” Paul Theroux again: “Fiction gives us a second chance that life denies us.”

In 1992 I quit the Pro Tour and started writing for surf magazines. For the first couple of years it was a revelation: I got to use my brain in ways that I hadn’t as a pro athlete; I was buttressed by a world I knew well. But the more I documented surf culture, the more monochromatic it became. When Westerly came along I jumped with excitement. Here was a story that had meat (sorry!) and depth and controversy. The surfing part I knew. The transgender part would be a great learning experience.

We met at a little Italian restaurant not far from where she lives on the Gold Coast. Westerly was dressed like a fifties bombshell and carried herself coquettishly, as if at any minute she could throw her handkerchief to the ground and revel as I dive for it. She wasted no time in laying down the facts. “This is the unfolding of someone experiencing a new existence,” she told me before the waiter had even brought us glasses of water. “I’ve been plucked and put into a new dimension. This is actually something that has come and hit me and said, ‘You’re ready. You’re ready to enter this new space and time and there’s a mission for you in all this.’”

For the next two hours, over plates of spaghetti arrabiata and strong lattes, she had me in her thrall. She spoke of Peter in the third person, lovingly, as if he were her tragic son who died a tragic death. She told me how as a child, Peter would paint his fingernails and wear lipstick and miniskirts — “He looked like a boy, but his emotions and sensitivities were like a girl.” She said that she named herself after the westerly wind, favorable for surfing on the Gold Coast where Peter grew up. She grimaced when she spoke of “the monsters that robbed poor Peter”, i.e. the surfing establishment that never gave him his due. Then she launched into the climax.

On a sunny afternoon in 2002, Peter Drouyn paddled out to his beloved Burleigh Heads. The sky was cloudless; the waves slightly overhead and spiralling down the point. He picked off a set wave and proceeded to streak across the shimmering face. On the inside section, where shallow sand creates a kind of zippering suck-up, he went to do his trademark straighten-out in which he adds a matador-like flourish, as if the lip were a charging bull. The wave clocked him square on the head. As it took him down, the left side of his face slapped the concrete-hard surface. He was held underwater for a preternaturally long time.

“This feeling is never to be forgotten,” remembered Westerly. “Peter felt terribly disoriented, his equilibrium was shot, he thought he was dead, he saw a powdery white light… and suddenly he popped up and drifted to shore.”

Westerly said that this accident, which left Peter with a concussion and perforated eardrum, “pretty much fried his brain”. She said things were never the same again, and that soon after he started changing into a female. She told a fairy tale-like story of Peter walking back from a surf one late afternoon. The beach is empty, Peter’s in a ponderous, introspective mood, when he nearly steps on a discarded women’s bathing suit, pink with white stripes. He takes it home and tries it on in front of the mirror. It fits. He sashays around the house in it regularly, often to the accompaniment of classical music. He experiments with lipstick. This leads to visits to local thrift stores, where he buys up women’s clothes by the bagful. In the middle of the night he puts them on, drives down to the beach, and dances along the shoreline in a kind of bewitched rapture. Pretty soon she’s wearing more women’s clothes than men’s.

“It was just bursting out of me,” said Westerly, “It was as if the suffering just couldn’t continue. And the moment I started believing I was a girl my body started to change. I went from a square gorilla to long-legged, slender. The hips are higher, the bum has lifted right up. The doctors can’t believe it!”

Westerly told me that she carries the spirit of Marilyn Monroe with her, that she’s on a kind of mission. “I want to bring back the power of femininity,” she said. “Everything I do — my speech, my communication, my clothes — is from the point of view of purity of femininity and the power of that internal spring; that caring, that sympathy, that sensitivity. A woman’s touch is finer than 16,000 magic carpets from Aladdin’s lamp! It can change the world.”

As I researched the piece, Westerly’s legend grew. Her friends and contemporaries weren’t buying it. “At sixty we men become invisible to the girls — Westerly just wants attention,” said one. “I saw him at the Stubbies Reunion night. He was wearing heels and lipstick. I asked him what the deal was and he pulled me in close and whispered, ‘It’s all an act,’” said another. “This is the greatest piece of performance art ever. Westerly should be in museums,” insisted a third.

While writing my piece I spoke with Westerly via Skype almost nightly. She spilled her guts — about how unfairly Peter was treated, about the “insensitive, backwards-thinking culture of Australia”, about her love for her son, Zach. “What I want more than anything,” she told me repeatedly, “is to get my operation.”

I got to thinking about identity. If Westerly were to have her surgery, would this silence the naysayers? If she were to change her mind, would this out her as a fraud? At what point does performance become real life? Aren’t we all to some degree acting?

My story appeared first in The Surfer’s Journal, then in magazines and on websites in Brazil, Australia, and Japan. It was the most commented on piece I’d ever written. I learned something I probably should have learned much earlier: a journalist is only as good as his/her story. I also learned that good stories essentially tell themselves, which is to say that I felt less like a prose/structure master and more like a midwife.

My friendship with Westerly continued after the piece was published. We spoke at least once a week. Along with her surgery, she wanted desperately to come to “America”, where she was destined to become a famous entertainer. As she fleshed out her version of “famous entertainer”, I was transported to the Marilyn Monroe 1950s. We discussed me writing a screenplay about her/Peter’s life, but we could never come to an agreement. Westerly had all kinds of stipulations. She oscillated from small-town ingénue to testy sixty-one-year-old prima donna making absurd demands. And she did the latter with almost a wink, as if it was all part of the persona.

Around that time I started to work with the director Alan White on a screenplay. Often our development meetings would drift into conversations about Westerly. Alan was as fascinated as I was. The hard facts of Westerly’s life, I realised, were far more interesting than anything I could dream up in a script. Not to mention the fact that documentaries are a lot easier to get off the ground than features.

In December 2011 Alan and I shot footage for a demo reel. We filmed Westerly at home and interviewed various surf luminaries. With producers Jordan Tappis and Beau Willimon, and musicians Matt Sweeney and Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, we brought our project to Kickstarter. Not only did we secure the funding we needed to get started on the film, but we learned that people were hungry for the Westerly story.

Which brings us back to Flight 474 to Bangkok. Westerly squirms in her seat. She triple-checks the stack of pre-surgery tests and psychiatric evaluations kept neatly in a pink notebook. She pulls from her purse a vintage hand mirror and applies a fresh coat of lipstick. As the plane makes its way down the runway she leans in close and sings in a breathy whisper:

I lost my love on the river and forever my heart will yearn,

Gone gone forever down the river of no return.

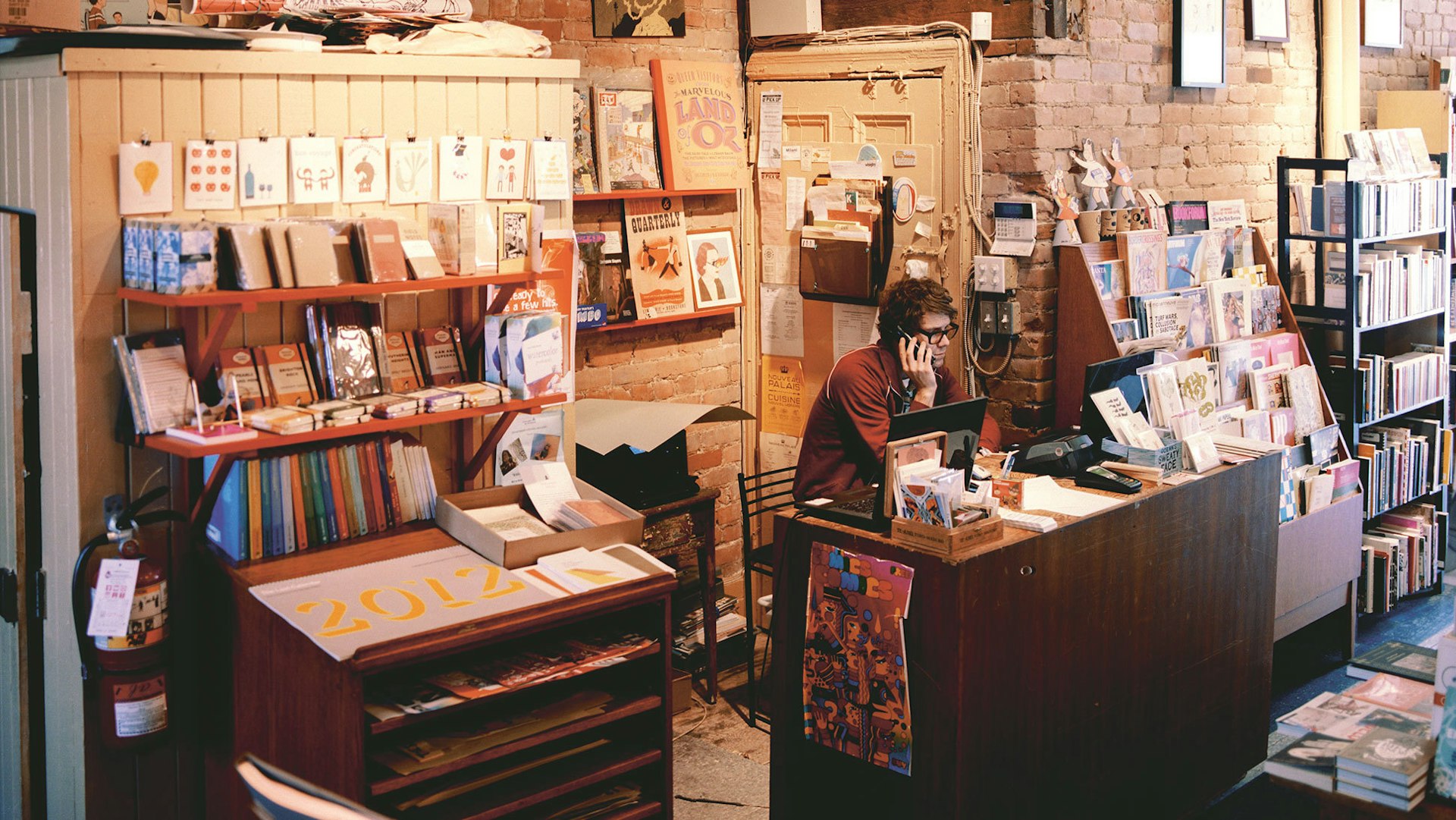

Join us for the European launch of Jamie Brisick’ new book, Becoming Westerly about surf champion Peter Drouyn’s transformation into Westerly Windina.

Join us for a reading and Q&A Huck’s Editor-at-Large Michael Fordham, followed by drinks and live music from The Loose Salute at Huck’s 71a Gallery in Shoreditch Tuesday July 28 from 6pm.

The event is free, all you have to do is RSVP here. 71a Gallery, 71a Leonard Street, London EC2A 4QS