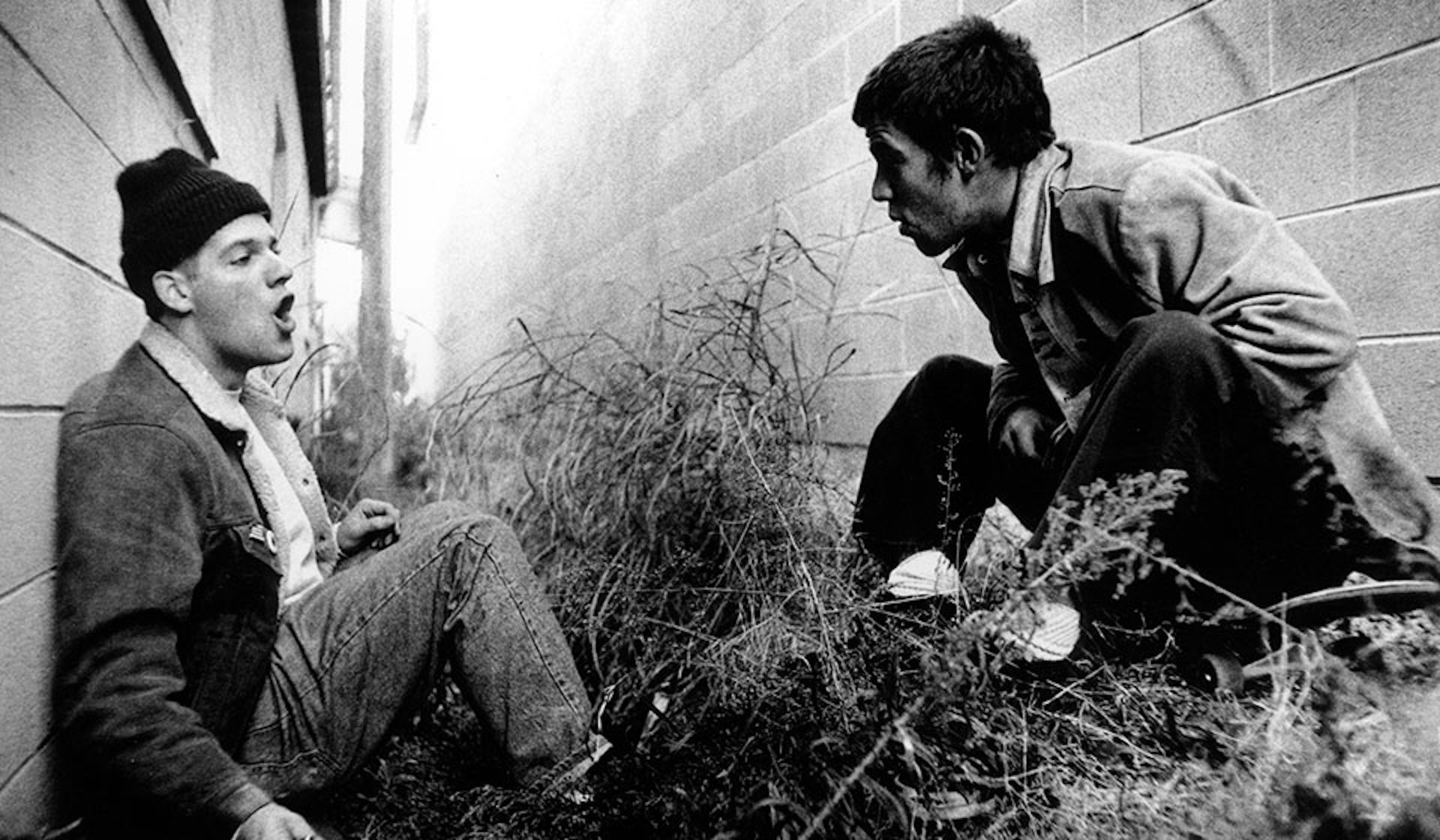

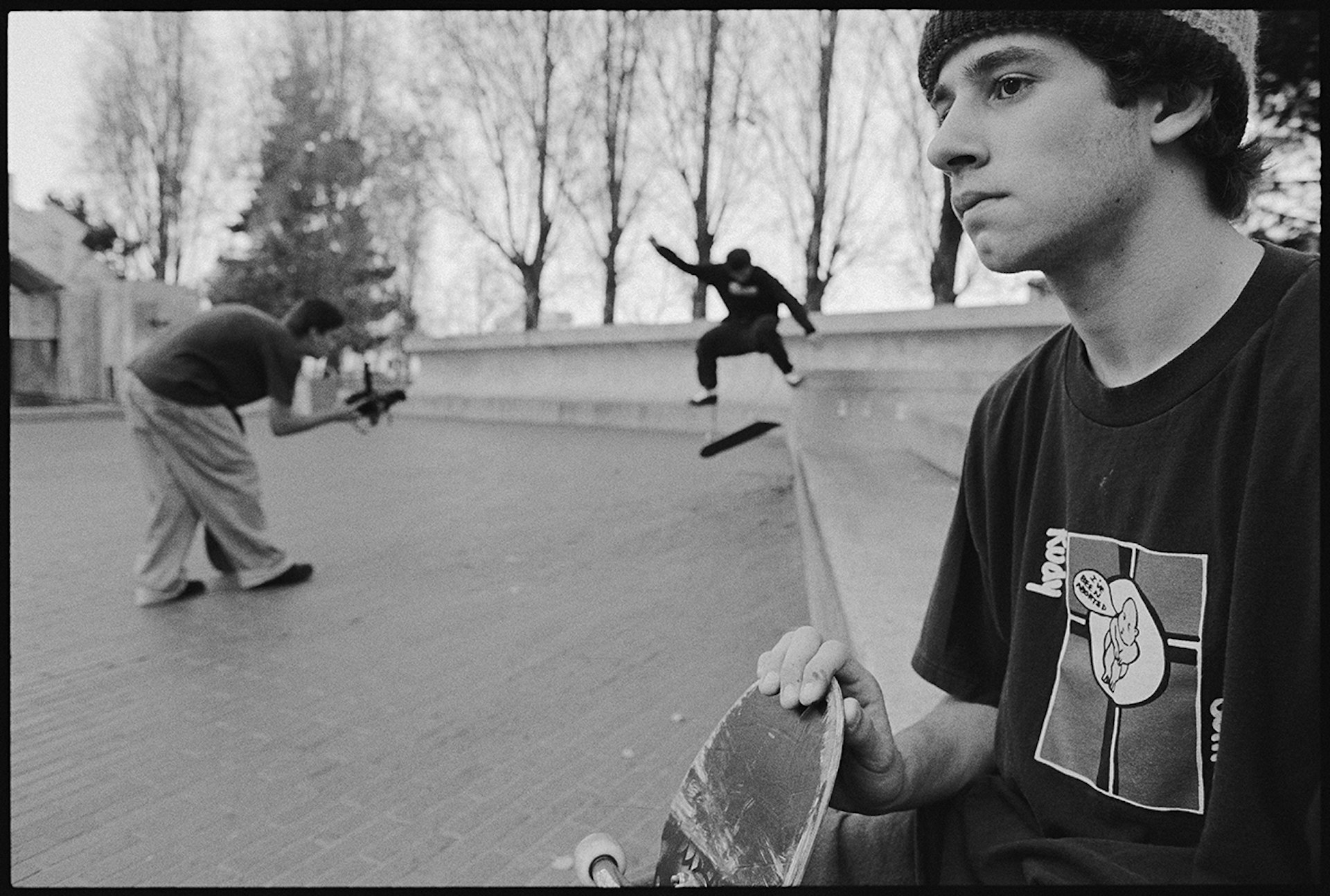

Tobin Yelland captures skateboarding at its most intimate

- Text by Shelley Jones

- Photography by Tobin Yelland

Tobin Yelland can predict the future.

It’s 10am on a Wednesday morning in LA and the photographer, filmmaker and artist – who helped shape the aesthetic of modern skateboarding by documenting its inner world in close proximity – is at his laptop in his garage-turned-studio outside his house in Venice, California.

“I’m guessing it’s going to be sunny today,” he laughs, eyes switching to the squares of light coming in under the door. He was up early to take his two kids to school and now he’s “out here making lists,” he says as he nudges a pen and notepad on his desk.

When Tobin points his camera somewhere, amazing things seem to happen.

Many of his most striking stills of skateboarding’s inner-world – Andy Roy shooting a gun at a range in Sacramento, Aaron Meza filming Chico Brenes in front of an oblivious Mike Carroll at Embarcadero, John Cardiel screaming in front of a Slayer poster, Jason Lee popping a can of coke next to a sleeping woman, a skateboard smashing into a car windscreen – hint at an almost supernatural ability to anticipate drama.

Tobin has a way of getting under someone’s skin to capture a moment. And rather than his work getting lost in the meta bloodbath of selfie-style, shoot-a-minute horseshit dumped on the internet every second, it just seems to get more and more powerful as time goes by.

The shapeshifting photographer, now 44, can channel the urgency of youth through a single shot and it’s a skill that hasn’t faded with age.

“I think finding the perfect moment to take a photograph is all about knowing that person really well,” says Tobin, whose easy nature makes him the perfect confidante.

“It helps to photograph a person over and over again so you can start to see things unfold before they really happen and you’re ready to take a picture. Also, when you’re that person with a camera in your group of people they maybe act out in front of you – so things happen. It’s just about creating that environment, which is really fun. I feel like it’s a rare moment but you know when you’ve got it, and it’s perfect.”

Tobin was born in Berkley, California, in 1970. His parents were both artists and he spent his baby years in the northern wilderness of the Golden State. After his parents divorced in 1973 he and his mother moved to San Francisco where he started skateboarding at eleven, took a class in photography at fourteen, and had his first pictures published in Thrasher at 15.

In 1987, aged 17, Tobin took a three-day photography course mentored in part by iconic subculture chronicler Larry Clark and he hasn’t really put his camera down since. “I think if I had my time again I definitely would not have gone to a photography school,” says Tobin, glancing sideways into memory space. “In four years of college I would have missed out on too much.”

Instead Tobin bedded down in the belly of the San Francisco skateboarding beast; shooting for scraps, living off burritos and sharing bathrooms with the likes of Bryce Kanights, Mickey Reyes, Luke Ogden and Julien Stranger.

He helped shape the visual output of iconic ’90s brands – shooting Stereo’s A Visual Sound in 1994, one of the first jazzy forays into arthouse skate celluloid, and Anti Hero’s Fucktards (1997), a raw love letter to San Francisco’s nascent street skateboarding scene.

He was prolific but at the core of all his productions was this constant curiosity about the human condition.

“I’m drawn to characters that are maybe a little crazy and really not self-editing all the time,” says Tobin, who takes a pop at contrived California in a funny short film, Encinitas Realization (1999), made by artist Chris Johanson.

“Hopefully they wear their heart on their sleeve. I think that’s the same for any photographer. [Anyone who] just lets themselves be photographed and is not self-conscious – it makes it a lot easier and fun.”

With the support of his creative misfit community, Tobin began to transcend the skate world. Artist Thomas Campbell hooked him up in a group show at Aaron Rose’s cultish Alleged gallery, Spike Jonze got him on commercials and he began shooting stills for movies.

Whatever the subject, Tobin was able to apply the immersive and roll-with-the-punches approach he learnt from society’s most self-destructive fringe. “Any subject that has life and energy is exciting to me,” says Tobin.

“I’m really grateful to have found skateboarding at a young age because it’s active and has taught me so much about perseverance and going for what you want to do, just because you want to do it. I have the fondest memories of skateboarding with my friends all over the city, all day long.

“Not having a concrete idea of where we were going but just pushing to find new skate spots and new experiences. Skateboarding got me out of the house and introduced me to all these people.

“First, I’m grateful to skateboarding, then I’m grateful to the artists who came out of skateboarding and carried on the creative journey into art and films or whatever.”

Self-employed again after a stint as video director at a brand, Tobin is zoning back in on the subcultures that spawned him.

In a series of recent documentaries presented by Vans Shoes he follows four photographers – Andrea Sonnenberg, Lele Saveri, Ray Potes and Clint Woodside – who shoot and self-publish their personal artwork through zines and blogs.

It’s a topic close to Tobin’s heart – the last book he read was Copies In Seconds, autobiography of the rags-to-riches inventor of the Xerox machine Chester Carlson who “got out of a shitty situation by inventing something himself”.

He loves documenting young people – because they’re “always ahead of everyone else” – but would he encourage his own kids down a similar DIY path?

“I would encourage my kids to make choices for themselves,” he says. “And hopefully not make life choices out of fear, like, ‘I have to do this because I have to be stable.’

“Even though I want them to be self-sufficient I think it’s more important for them to do what they really want to do. They might follow some wild hair of an idea like, ‘I want to be in the circus!’ But what’s the worst that could happen? They might fail and then they’d have to work something else out.”

In his life and work there’s an openness and ambiguity to Tobin Yelland that lets people draw their own conclusions. He’s been an inspiration at skateboarding’s centre.

UK skate photographer Sam Ashley sums his influence up: “Not only did he shoot the rawest skaters, he shot them in a way that gave you an insight into their crazy world, beyond just the skateboarding. It was clear that this wasn’t someone just observing from a distance, he was an integral part of things, too.”

But there’s something even more universal about his appeal. Every shot, and every sentence, seems to hint at a world of stories underneath. Is it something he’s aware of?

“I’m really honoured if I’ve inspired people – so many people inspire me,” says Tobin, who cites visual anthropologists like Jacob Holdt, Mike Brodie, Craig Stecyk, Peter Sutherland and Ari Marcopoulos as favourites.

“I would hope that some of my work shows something about people that no one’s ever seen before. And I hope I can continue to show something new… Hopefully there’s an honesty, too, between me and who I’m photographing.

“I feel like everyone can appreciate an honest answer from someone. A no bullshit presentation. That’s what I hope my work is. It could be crazy or it could just be a normal moment. But it’s something everyone can understand.”

This story first appeared in Huck 45 – The Ed Templeton Issue. Get it from the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you don’t miss another issue.