Handmade Boards

- Text by Jon Coen

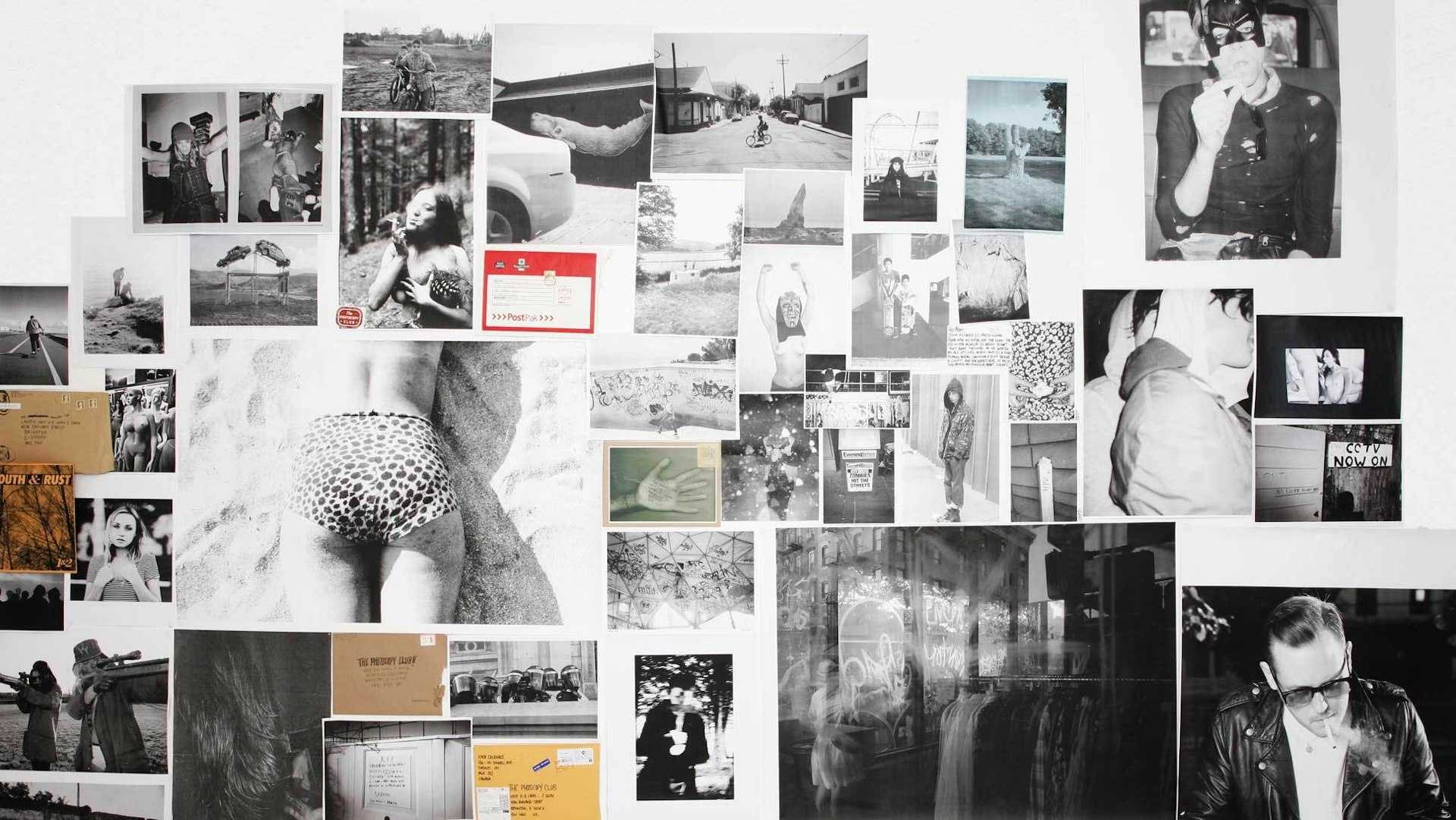

- Photography by Nick Lavecchia, Shem Roose

It’s funny. We all remember where we were on December 5, 2005 (aka ‘Blank Monday’) when Grubby Clark closed his Laguna Nigel foam factory for the last time. It was a wake-up call. The seventy-two-year-old had supplied the polyurethane foam for a good eighty per cent of the world’s surfboards. But no amount of monopolistic market share could combat the fact that volatile organic compounds were a major catalyst in the decision to shut shop. And rightfully so – because, as soon as the dust settled around old Grubby, we were all reminded that foam and fibreglass are both toxic materials.

For the majority of eco-minded boardriders, it was a reminder that our primary tool is petroleum based – as are our wetsuits, booties, snowboards, bindings, outerwear, watches and must-have bags. If it weren’t for the seven plies of maple we kick around the street, we’d be total assholes. Well, hypocrites at least.

Almost every piece of gear we use to access nature is a detriment to it. And despite our desire to ‘carve a different path’, we sure do resemble the society we aimed to set ourselves apart from – worshipping idols (aka ‘ambassadors’) employed to divert our attention away from the fact that, despite the pretty logos, they’re all just moving units. It stands to reason that in the Northeast region of the US, the geographical and metaphorical opposite of Southern California where ninety-nine per cent of the industry is based, there should exist a pair of companies – Grain Surfboards and PowderJet Snowboards – that are living the freethinking mantra, not just marketing it.

“What we do is give people a choice,” says Brad Anderson, the fifty-one-year old co-owner of Grain Surfboards, whose life resume includes ship captain, land conservation director and wood worker. “If you can live by the values that you feel strongly about and make those present in your product, then it gives all those other surfers out there, who may be inclined that way, a choice. It’s a choice to adhere to those values – to get a surfboard that doesn’t make them feel like they’re betraying everything that they believe in.”

The stories of Grain Surfboards and PowderJet Snowboards – based in Vermont and Maine, respectively – aren’t just intertwined with New England’s heritage of hand-wrought craft, but also with each other. Grain founder Mike LaVecchia and PowderJet’s Jesse Loomis met in the early 1990s and both wound up working at Burton’s Burlington HQ. Although it wasn’t until 2005 that the idea of the wooden surfboard took root in Mike’s mind, the next decade played out as an apprenticeship of sorts.

Working right on Lake Champlain, Mike bought and restored a wooden boat, then left Burton in 1995 to spend two months sailing a thirty-eight-foot sailboat to the Florida Keys. He earned his captain’s license, launched a sailing charter operation and, by 2001, was hired by the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum to build a replica of an eighty-eight-foot, 1862-class Canal schooner, which had sunk in 1876. Jesse, meanwhile, discovered he wasn’t a shabby lensman and moved to California to take up a photography position at Transworld Snowboarding. But by 1998, he was back on the East Coast honing a new skill. “My wife and I bought a house in Burlington, and I started learning some basic carpentry in order to fix it up. When we got preggers in 2000, we decided to move out to the country to raise feral children, and I became a full time carpenter,” he recalls.

In 2005, Mike moved to Maine and built his first wooden surfboard. Soon after, spurred by his interest in conservation and craft, Brad Anderson stopped by to check things out. Like Mike, he’d started surfing later in life and neither was enamoured with the idea of buying a board straight off the rack. “The first time I called him was out of the blue I had to look up his name in the white pages. There was no ‘Grain’ yet – he was still in the basement,” recalls Brad. “He was working in a cave – no light, a few crappy tools, a couple of boards, aborted frame tests, scraps and shit everywhere, all covered with dust. It was like he was a cave-dwelling surf terrorist secretly preparing an attack on an infidel industry who’d gotten away with building an evil empire of toxic wave-toys for too long.”

By 2006, Brad was a co-owner and a few months later they moved to their current location, a farm just a few miles from York Beach, on the southern coast of Maine. Soon they were shaping boards, selling ‘Homegrown’ kits to hands-on surfers and hosting weeklong classes at their shop, all the while cultivating a worldwide following of surfers and hobbyists eager to be part of a DIY community.

“There’s just constant motion and always a good feeling at Grain,” explains Jesse, who shaped the odd surf craft from his mountain workshop for Grain. “I thought they had such a great idea. It was eco-sensitive and different from the normal surfboard. It took about two years to say, ‘What the hell? Why don’t I just do this with snowboards?’ It makes so much more sense for me, living in Vermont.”

By January 2009, Jesse was ready to snow-test his first board on the wooded hillside near his home. “I followed the old logging road up into the trees, then stopped for a minute to catch my breath. I was pretty nervous that the board was going to feel wonky, awkward or just wrong. Before I could spend too much time thinking about it, I strapped in, pointed the nose down the logging road and straight-lined it… I couldn’t believe it rode exactly the way I’d hoped it would. From that point on it was just laughter – a solitary fool on the hill just laughing.”

Grain’s testing ground is just as quaint. Long Sands, the jewel of Maine’s York Beach, is a two-mile sandy nook on a coastline known for rocky crannies that attracts droves of Massachusetts tourists (affectionately referred to by locals as ‘Massholes’) who battle for blanket space all summer long. Around every corner are lobster rolls, hand-knitted scarves, organic eggs and wood-roasted coffee. Maine does have its secret spots – some guarded by shotgun-toting lobsterman, others just by the stories of such. Long Sands just isn’t one of them with plenty of room to find a peak.

Today, it’s an unseasonably warm February evening, so we head out to snag waves on wood. Scoring anything in the Northeast – frozen or fluid lines – is like wooing a temperamental lover. The mountains aren’t as dramatic as the west. Snowfall is erratic. Aside from autumn hurricanes, the surf usually depends on short windswell from tempests moving off the East Coast. And while winter offers intimate moments of deep passion, it can too often be a long, trying relationship that ends in bitter death. But everything about New England lends itself to tradition and old-world craft. This is the first place colonists settled in North America. And while the architecture may seem pubescent to Europeans, it exudes history by New World standards.

“You go into one antique store in an old barn and you’re melting from the sense of craftsmanship,” says Brad. “The fact that someone built that, with all that joinery, just to put his cows in. It’s inspiring.”

There’s a small get-together at the Grain shop later that night in aid of Mike’s sister-in-law’s birthday, and Jesse has driven out to the coast to join in. Over homemade cupcakes and microbrews, folks wander around the workshop to admire the boards, including a few that the Vans art department flew out from LA to make a week earlier.

Mike and Jesse are both bearded and clad in flannels, woolies and work pants – a functional uniform for the New England craftsman, whether building cabinets or snowboards. “I’m always discovering things that are incredible to me from the barns to boat builders tucked away in little pockets,” says Mike. “There’s one down the road who’s been building boats for thirty-five years. And he learned from a guy who built boats for thirty-five years before him. He’s using tools that are a hundred years old, passed on.”

“Many of our personal hand tools are these old antiques that we found in barns and cobbled together to keep alive,” Brad interjects. “We’re all inheritors of that aspect of quality, craftsmanship and care. Everywhere you look here, you just feel it.”

It’s a refrain uttered repeatedly. One customer even describes his Grain as having “the warmth of a living being”. And, as odd as that may sound, there may well be some truth in it. Alongside their commitment to life-cycle analysis – where they “interrupt the waste stream” to repurpose someone else’s trash – Grain are determined to pioneer a greener business model. Wood shavings are carefully collected and used as bedding for the animals on the farm. No employee of Grain commutes more than twenty minutes from the factory. Hand planes are finished with whey – a by-product of Vermont cheese as an alternative to polyurethane. And lumber off-cuts become ‘Sea Sleds’ or skateboards. They recently inked a deal with Fyne Boatworks, who will distribute Homegrown kits in the UK made of Douglas fir, ash, Larch and spruce from managed woodlands in England.

But things, they admit, are far from perfect. Even after carcinogenic foam has been cut out of the surfboard equation, the wood still has to be wrapped in something – and fibreglass is still the only option. They may have found an epoxy for their glassing process that emits zero volatile organic compounds, and a type of bioresin that’s thirty-five per cent organic, but in the spirit of transparency, the Grain website discloses each and every sticking point, in the hope that consumers will push them to up their game.

But if there’s one thing they’re proud of, it’s gotta be the wood. “We are unequivocal about using sustainably harvested wood,” says Brad of the Northern White Cedar from which they assemble the boards. “It’s been over-cut in other areas, but for us, it’s local and renewable. Human history is rife with examples of people thinking a resource would never run out and time has always proved that to be an error in judgement.”

As midnight passes, the party turns into a cupcake war. Icing-coated revellers teeter homeward, but convening in the quiet office Brad, Jesse and Mike’s conversation turns toward the bigger picture.

“There’s a certain segment of the boardsports culture that’s going to be attracted to what we do, and what Jet does,” says Brad. “It’s not like it’s going to sweep the culture, sweep the industry or sweep public consciousness. But it’s not a novelty like, say, a coloured condom. There’s something real and meaningful here that a certain type of person is going to be attracted to like fine art, poetry, or anything that [is more than just] a manufactured plastic product.”

While a demand for hand-shaped surfboards has thrived, snowboarding, as Jesse points out, has been slower to catch up. It’s only now, after two decades of mass-production, that pockets of riders are visibly crafting their own sleds. But is the nature of wooden, handcrafted boards sustainable – in the real-world, economic sense of the word? Can ex-Burton employees run small businesses in a world where their former employer is growing bigger by the day, buying up brands like Channel Islands Surfboards, and energy drink companies have bigger media budgets than the media?

“It’s not much of a revolution as far as the industry is concerned. We don’t have any interest in attacking them or what they do – we’re only interested in offering choices that weren’t really there before,” says Brad.

And people, it seems, are making the most of this freedom of choice. Even board-riding luminaries, like Portland snow anarchistScotty Wittlake, are proponents of these companies. Ocean activistDave Rastovich enjoyed his 5’10 Grain ‘Waka’ so much that he built a 6’10 ‘Radicle’ pintail on the lawn of the Billabong house at Pipeline. Kassia Meador and Mikey DeTemple came up and crafted a few. And seven-time world champ Layne Beachley helped design the 7’0 ‘Pandan’.

Is it possible that a generation who started out building their own ramps, ordering sticks from the local shaper and duct-taping hand-me-down snow gear are now looking for a way to re-access those roots? “People who are contacting me are into the whole concept of looking away from the Shaun White version of snowboarding – the over-the-top, branded, maniacal, sport. The board itself is a pretty aggressive ride, but it’s a lateral move,” says Jesse.

Consumer society has become so dependent on inexpensive plastic shit from Asia that we toss anything that has lost its appeal. It’s largely an American trait spread like a venereal disease from the US like polyethylene herpes. Planned obsolescence kills quality. Neither Jet nor Grain is looking to tear down the establishment. But maybe in addition to learning to grow our own food, supporting independent record labels, and fixing our own vehicles, more of us are looking for a way to reconnect with the most important objects in our lives.

“I don’t think what we do has much at all to do with the industry, marketability of surfboards or consumer patterns,” says Brad. “It’s far more of an act of creativity and passion that we’re involved in, the way a painter cares about creating a piece of art. I’m not saying we’re equivalent to some fine artist or anything, but it’s like that. You could have a hundred ways to decorate the inside of your house – a painting, sculpture, or photograph by someone who’s really trying to express something. That’s kind of what we’ve created – something that comes from the heart.”