Jack O'Neill

- Text by Michael Fordham

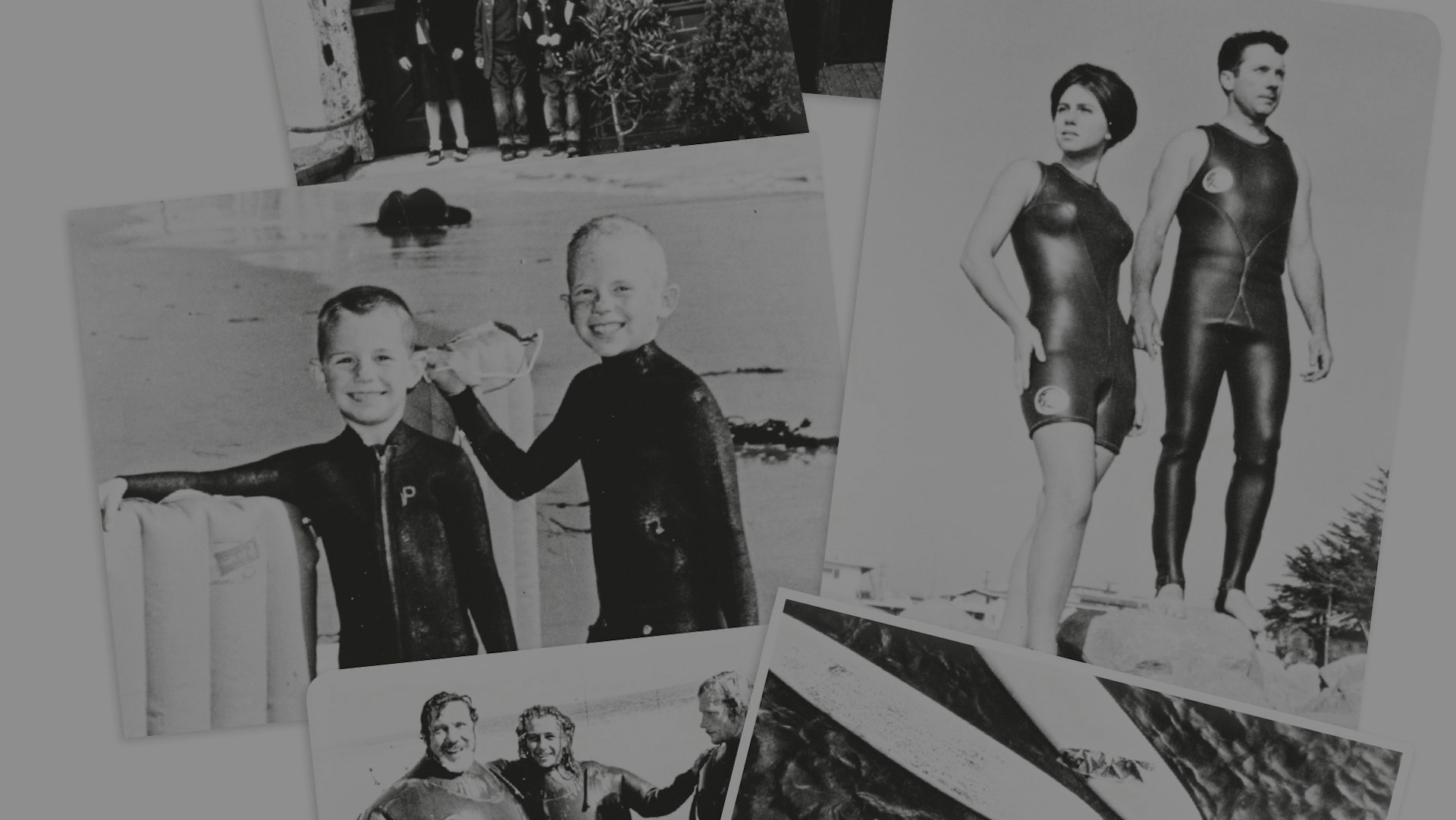

- Photography by O'Neill Archive

This year, Jack O’Neill and his crew are celebrating sixty years in the game. And whichever consumer choice you make when planning your rubber fetish for any given surf season, you owe a debt of gratitude to the man. Drew Kampion’s entertaining tome on the life and times of the Navy pilot-turned-surf entrepreneur helps explain why.

Hardback-bound and coffee table-ready, Jack O’Neill: It’s Always Summer on the Inside is a gigantic archive of first-person narratives and old family-album finds that, together, retrace one of surfing’s most transformative leaps. You see, without Jack’s innovative vision – which has sustained in a triumphal arc these last six decades – the colder watery regions of the world might never have been opened up for surfing’s elemental creed.

“We had no protection from the cold – no wetsuits or anything, and I never got much out of those wool sweaters,” remembers Jack of his early surfing days at Kelly’s Cove, San Francisco, in the 1950s. “We used to run down the beach to get warm before swimming out.”

In the pre-war years surfing in cold water couldn’t have been a barrel of laughs. Hardy brethren would huddle around a fire, sipping on hits of rum and whisky while gingerly eyeing up the freezing winter sets, picking the moment with a little Dutch courage to pull on their woollen jerseys and thermal pants and run to the shore, knee-paddling out for a quick, breathtaking bump and grind. Duck-dives and wipe-outs – anything that kept a body submerged – were to be avoided at all costs. Elegant, dry-haired paddle-outs and nonchalant, stylish kick-outs not only demonstrated surfing prowess and the stylish aesthetic of the times, but were techniques a surfer could use to stay relatively warm and dry.

Then World War Two came and changed all that. That twisted silver lining transformed a million things – in surfing it helped speed up the introduction of fibreglass technology and, of course, the wetsuit, which up until that point was still a seedling of an idea, yet to manifest in Jack O’Neill’s Surf Shop.

Hugh Bradner, a physicist working at the University of California, Berkeley, in the early 1940s is widely credited with coming up with the concept central to the success of the wetsuit: namely that it didn’t have to be watertight to keep the wearer warm. Bradner’s research was commissioned by the US Navy who were keen to find a way to keep military divers in the water longer and to keep them fighting fit and flexible.

Bradner realised that by using various types of rubber, PVC and other materials, a suit could achieve thermal insulation from the many tiny bubbles of air trapped in its material. Water could saturate the suit and the bubbles of water would heat up between the swimmer’s skin and the suit’s exterior surface.

When the Navy officially declassified the PVC insulating technology for their divers’ suits in 1951 it led to a flood of experimentation. Jack in particular found himself picking up frogman suits in surplus stores in the pursuit of a warmer surf.

“[I started] experimenting with ways to keep warm. One guy told me that after the five guys on the beach got outfitted, I would be out of business,” he says.

Jack quickly realised that a more flexible version of the Navy wetsuit would mean more water time for the wearer.

But the real breakthrough came when he discovered an interesting, rubber-like industrial substance: neoprene. So, he made a bulk order and started experimenting, stitching together long johns, vests, beaver-tail jackets and custom-made full-body suits.

“In the beginning, the neoprene came with two smooth sides, so getting them on was difficult,” remembers Jack. “[We would] put talcum powder on ‘em. One guy put flour on and it stuck. […] Basically, you had to put the wetsuit inside out and peel it on, starting from the ankles. But most people who wanted a full suit just got a long john and wore that under a beaver-tail jacket. Those were good sellers. People had never been that warm in the ocean.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Thanks to Jack’s pioneering post-war invention, surfers have been able to tackle even the most frigid of breaks in the four corners of the globe, and stay out in the water for as long as they like.

Bravo to that.