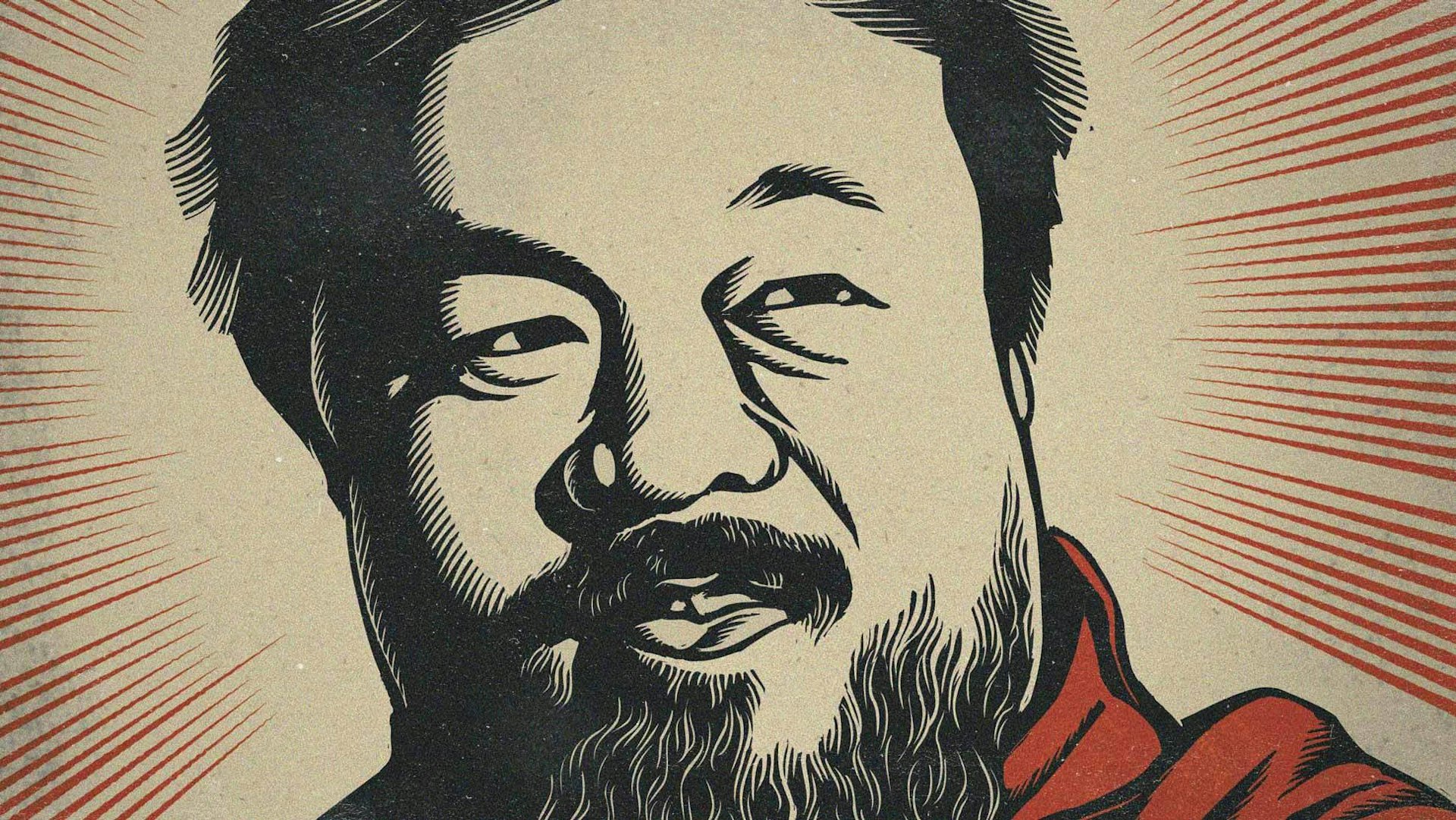

Jack Robinson

- Text by Jed Smith

- Photography by Jimmicane/A-Frame

In the pre-dawn darkness of remote Indonesia, the yacht creaks and a rope clangs against the mast. Out towards the bow, the tiny frame of Jack Robinson sits alone, peering into the darkness.

“It’s pumping out there. Look at this one,” he says as I approach, before the unmistakable crack of water against reef and the gentle phwooosh of air out the end of a tube confirms it.

It’s day one of Jack’s first trip to the Mentawais and he’s been awake all night at the prospect of surfing. When the sun pokes over the jungle in a few minutes time, we will see six to eight feet of Indian Ocean fury marching towards the reef in front of us. And a crowd of onlookers will learn whether the most heralded junior since Kelly Slater is worth his hype, or, what it sounds like when a child screams for his mama, forty hours from home.

At thirteen years old, Jack is already one of the most recognisable surfers in Australia. He’s twice been the subject of major bidding wars (Quiksilver’s won both times, recently extending his contract for another three years). While the plaudits continue to come from the sport’s best.

“Apart from having an unbelievable amount of talent, he has a crazy amount of feel for the ocean and the lineup,” says Modern Collective star and Margaret River local Yadin Nicol, who has watched Jack’s development over a number of years. “He can position himself in a lineup of pro surfers and know where to be when the best wave comes. I haven’t seen anything like it.”

West Australia’s other favourite son Taj Burrow has been similarly impressed. “Every time I’ve seen him surf he’s blown me away. He’s got freakish talent,” he says. Jack’s competitive record is equally impressive. By the age of twelve he’d claimed all three divisions of the West Australian titles (the under 12s as an eight-year-old, the under 16s aged ten and the under 18s aged twelve), and kicked off 2011 with wins in the under 16s divisions of the coveted King of the Groms contest at Snapper Rocks and the Taj Small Fries event in Yallingup.

But his success has also raised concerns about the ethics of rearing a child into a surfing super-athlete. His parents recently came under heavy criticism from the Australian press for removing him from school to concentrate on surfing. If Jack is suffering, he’s not showing it yet. “I’ve got the best life in the world. I can’t believe it,” he says back in Indonesia, before leaping theatrically overboard and making his way into the lineup.

When a bomb morphs out of the horizon, sending a boatload of South African businessman sharing the lineup with us scrambling for the channel, Jack paddles deeper. As the lump lurches, his tiny arms spin furiously, pushing his forty-one-kilo frame over the ledge. With a blank expression and eyes slightly narrowed he takes off, plunging at the coral before a deft drop-knee, grab-rail bottom-turn pulls him up and into the tube. A cheer from the boat a few seconds later signals his safe exit.

The businessmen return to the lineup. “Fucking unbelievable!” exclaims one. “For a second there, I thought he was dead for sure.”