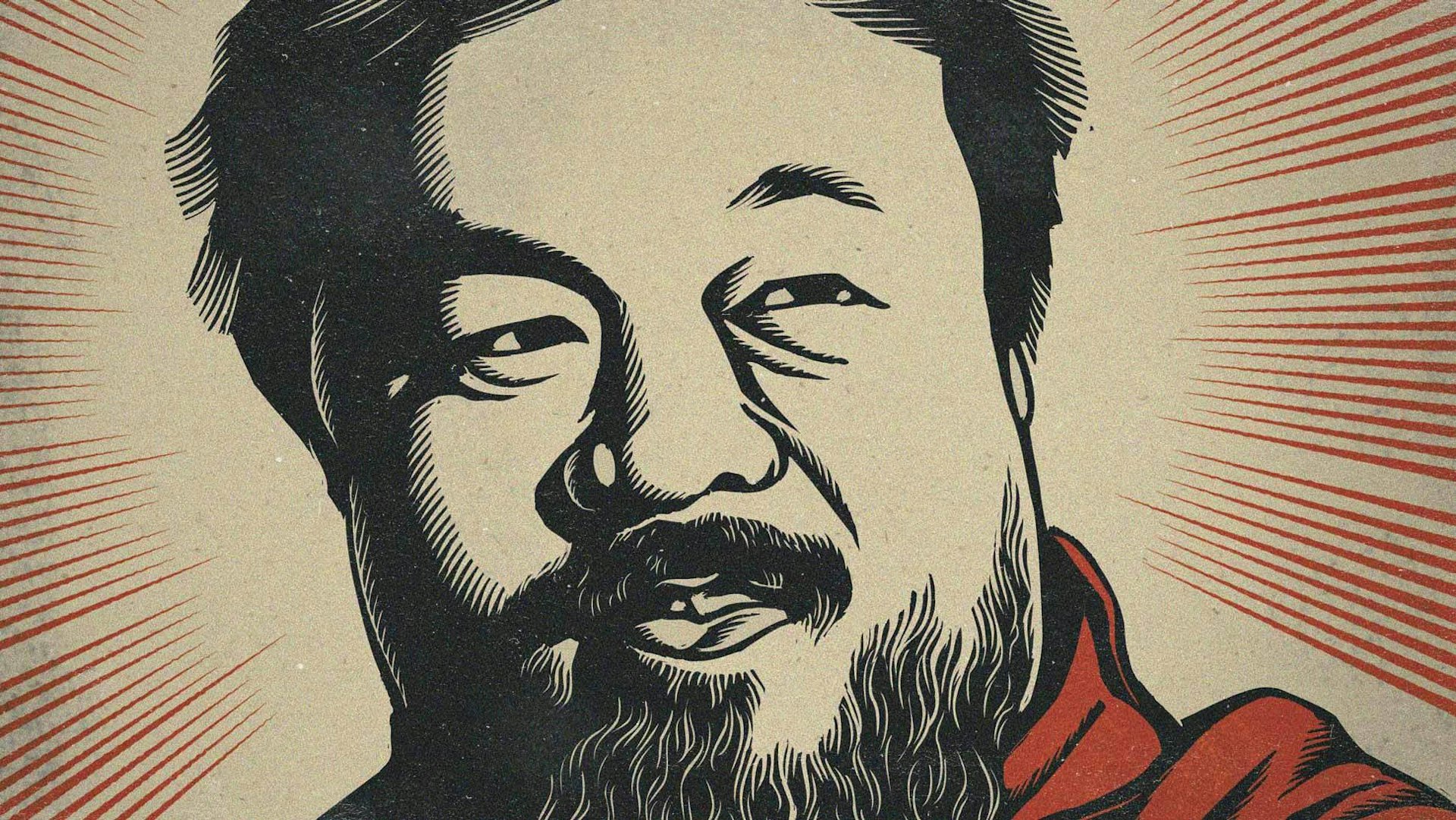

Ai Weiwei

- Text by John Sunyer

- Illustrations by Chris Gall

Ai Weiwei is a difficult man to interview. Not because he’s difficult to talk to. He’s just incredibly careful about what he says. That’s what happens when you’ve just been detained by your government for nearly three months without being able to tell anyone where the hell you are.

In early April, Weiwei’s persistent criticism of the Chinese regime led to his disappearance somewhere in Beijing. His arrest for unspecified “economic crimes” was part of a vicious crackdown on dissident artists, writers and lawyers by the Chinese authorities, who feared an Arab Spring-inspired revolt. Then on June 22, eighty-one days later, Weiwei reappeared at home.

In one of the first interviews since his detention, Weiwei opens with an apology; he explains he can’t tell me about the conditions of his release. “I’m out, I’m home, I’m fine,” he says on the phone. Not free, but “out”, which can mean something closer to house arrest.

He explains that he is still producing art, although he has to “digress” from the more political aesthetic that made him China’s first global art star. “Please understand that I can’t talk about what kind of art I’m making now. It reflects my current position,” he says, before trailing off mid sentence.

In July, Weiwei accepted a teaching post at the Berlin University of the Arts. Is leaving China his only hope? “It will bring out my creativity and give me the chance to work with young people. But it’s hard to know when I can go,” he says, cagily.

The interview lasts for about fifteen minutes, but most of what Weiwei says is unprintable. At the end of the call, I ask him if he wants to leave China and what he thinks about the Chinese dissidents that have already left. “I never wanted to leave China. But I am not allowed to talk to the media about this at all,” he says. “Please understand you can’t print this. I think I’m allowed to say that I’m happy for them and everyone else who makes their own choice and has the freedom to feel liberal.” And with that, our conversation ends.

These blank spaces speak volumes in their own way. Anything you want to know about Weiwei – his birth in 1957 to outspoken poet parents; his twelve years in America surrounded by the Warhol-influenced art scene; his expertise at blackjack, prolific Twittering, and the emergency brain surgery he had to undergo to repair a burst blood vessel, reportedly caused by a severe police beating – it’s all just a Google search away. But what happened during his detention is anyone’s guess.

“It’s well-known that torture in custody is rampant in China,” says Phelim Kine, a senior Asia researcher with the New York-based Human Rights Watch. “The Chinese regime uses criminal and thuggish methods to silence dissent. […] It’s becoming distressingly routine for the authorities to pay absolutely no attention to the law. Since mid February, they’ve thrown the rulebook out the window.”

Plain-clothes security officers follow Weiwei everywhere. He must ask for permission to travel outside of Beijing. He is banned from using Twitter or blogging. His passport remains seized. And yet he has not been formally charged. “Ai Weiwei is in limbo,” says Kine. “He’s in a legal grey zone, which is exactly where the Chinese authorities want him.” To combat this, says Kine, the high-profile campaign for his emancipation must continue. “It’s only when there is long-term public pressure that conditions begin to change.”

PEN International, a worldwide organisation that campaigns for freedom of speech, has seen its Chinese centre take on fourteen new cases – including Ai Weiwei’s – in the last six months. “We’ve been contacting the families and lawyers of detainees, appealing for donations for humanitarian and legal support through our website internationalpen.org.uk and publishing some of the banned works,” says Yu Zhang, executive secretary of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre.

Weiwei won notoriety for destroying Chinese antiquities to create new works, a comment on the denial – and indeed destruction – of China’s rich cultural history by this and previous governments. There’s the daring picture of his wife, Lu Qing, lifting her skirt to reveal her white knickers as she stands in front of an iconic Chairman Mao portrait at the gate to the Forbidden City in Beijing. Equally provocative is ‘Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn’, a triptych of photographs in which Weiwei is seen casually dropping a two-thousand-year-old vase to shatter on the ground. And in 2000, he seriously tested the patience of the Chinese authorities when he co-curated an exhibition in Shanghai called Fuck Off. The show included a series of photographs called ‘Eating People’ in which another artist is seen cooking and eating what appear to be aborted human foetuses. Authorities promptly closed down the show.

In an interview with Weiwei in 2010, I asked what it felt like to be both one of China’s most recognisable artists and one of its highest-profile critics. “It would be easier if there were other artists with the same influence as me to share the burden,” he said. “There is so much attention on everything I do, but it’s my job. I have to do this.”

I also asked if there was a distinction between his art and activism. “Sometimes my work is political, sometimes it is architectural, sometimes it is artistic,” he explained. “I don’t think I am a dissident artist. I see them as a dissident government.”

The severity of the recent crackdown has led many to agree. Dozens of artists and writers that support Weiwei’s call for freedom of speech have been abducted, tortured and imprisoned in the last five months. Given the authorities’ bullyboy tactics and the constant threat of prison, many have been forced to choose between the insidious force of self-censorship and exile: stay silent, or leave.

Take Murong Xuecun, the pen name of Hao Qun. The thirty-seven-year-old is considered one of the most famous authors to have emerged in contemporary China. In his damning and unflattering portrait of modern China Leave Me Alone: A Novel of Chengdu, we follow three young men beset by dead-end jobs, drugs, gambling debts and whoring as they struggle to make their way in Chengdu, the country’s fifth most populous city.

Murong attempts to sidestep the absurdities of the censorship system by using his “powers of obfuscation”. In other words, he writes about sensitive subjects without putting damning words onto the page. This is a heavy burden for a writer to carry. “The censorship machine is invincible. Sometimes it can be impossible to fully resist and oppose,” he says.

But Murong remains defiant. In 2010, a non-fiction work, The Missing Ingredient, about going underground to uncover a fraudulent business scheme, won him the People’s Literature Prize, but he was unexpectedly barred from making an acceptance speech. Instead, in a bold riposte to the Chinese authorities, he mimed fastening a zip across his mouth as he waited on the podium to collect his award.

The New York Times later published Murong’s planned acceptance speech in which he declares: “I am a proactive eunuch, I castrate myself even before the surgeon raises his scalpel. Our language has been cut into two parts: one safe, and the other risky.”

Chen Xiwo, a novelist and professor of comparative literature, puts it more simply: “Unless you keep your mouth shut, you’ll come under pressure very early,” he says. In 2007, Chen launched a legal case against China Customs for confiscating copies of his own short story, I Love My Mum, which were being delivered to him from Taiwan. The novella centres on a disabled man who is in an incestuous relationship with his mother and, at her demand and using a whip she provides, beats her to death. Censors quickly labelled the book “anti-human”.

Some Chinese dissidents are prepared to leave China to fully pursue their right to freedom of speech. The Chinese writer, poet and folk musician Liao Yiwu has spent much of his life in and out of Chinese prisons, largely because he insists on describing the realities of Chinese life in unrelenting detail as he sees it. The German edition of his memoir, The Witness of the 4th of June, is finally set for release this August.

The book was supposed to be published in April, Liao tells me over the phone, with his friend, Yeemei Guo, as our interpreter. “I received very serious warnings that if my book was published, I would ‘disappear’ for a while and be put in some kind of jail,” he says.

On July 6, Liao fled to Berlin – after being denied an exit visa seventeen times and forcibly taken off trains and planes by the authorities – to tell the “ordinary story of Chinese people”. His self-exile means he is now safe and feels liberated. “I’m finally free. It feels like I’m dreaming. It is not my life goal to criticise the regime, but I am an independent writer. I want to be the witness of history and speak for all of the Chinese people who feel suppressed,” he says, adding that his writing is the most important thing in his life.

It is, however, becoming more dangerous to speak out. In his new e-book, Liu Xiaobo’s Empty Chair: Chronicling the Reform Movement Beijing Fears Most, Perry Link investigates China’s “stability maintenance”. This includes monitoring people – disgruntled workers, lawyers, religious believers – in order to stop “trouble”. Link writes: “In 2010 China spent 514 billion yuan on ‘stability maintenance’ – more than it spent on health, education or its social welfare programmes and second only to the 532 billion yuan it spent on the military.” This year, the “stability maintenance” budget is at a record high.

But exile – whether forced or self-imposed – has its problems. “It has been very clear for more than a decade that exiles lose their influence inside China,” Link explains in an email, before listing sixteen famous dissidents who never regained the attention they once commanded after they went into exile. “I have also seen cases in the last two years [of dissidents] who have rushed back to China just so that they won’t be barred from going home when something sensitive is approaching.”

For the fifty-eight-year-old Chinese writer Ma Jian, this warning comes too late. Ma, author of the acclaimed Red Dust and Beijing Coma, has lived in the UK with his partner and translator Flora Drew since 1997. Staying in China was never an option. “Whenever I put pen to paper, I was always glancing at the door, waiting for the police to walk in,” he says.

Although his works are banned on the mainland, Ma has visited “hundreds of times” since he left. But in July, he was barred entry without receiving any official explanation as to why. His situation is indicative of how things have deteriorated since the crackdown in February.

“It reminds me of the repressive period that followed the Tiananmen massacre of 1989,” says Ma, who wrote an explosive fictional account of this period in Beijing Coma, which tackled the horrors of how Chinese security forces killed up to seven thousand students and supporters who had been demonstrating for democratic reform for over six weeks.

According to Ma, there is a new sense of “dread and trepidation” whenever he speaks to his Chinese friends on the phone. “Their voices sound knotted and strained. They’re terrified of being overheard saying something they shouldn’t,” he says. “But I won’t let any of this alter the way I think and write.”

I can’t help but think back to a party I attended last year at Ai Weiwei’s studio on the outskirts of Shanghai. While an ankle-deep mound of sunflower seeds captivated visitors at London’s Tate Modern, Weiwei was under house arrest back in Beijing. The Chinese government had ordered the demolition of his new £750,000 studio because of complications surrounding the planning permission. Weiwei organised a party to “celebrate” but was banned from attending. The party went on without its host.

Under a hazy blue sky, with five hundred people feasting on local delicacies, like river crabs and steamed buns, one lady carefully unfurled a poster. She gathered another protestor standing nearby and gave them a corner to pull tight for the cameras. The ubiquitous face of Ai Weiwei shined back. Part of the right side of his head was shaven, revealing scars from the emergency operation he underwent, allegedly after the police beat him. “The state media don’t report our protests,” she said. “They can threaten us all they like, but we won’t go away.”