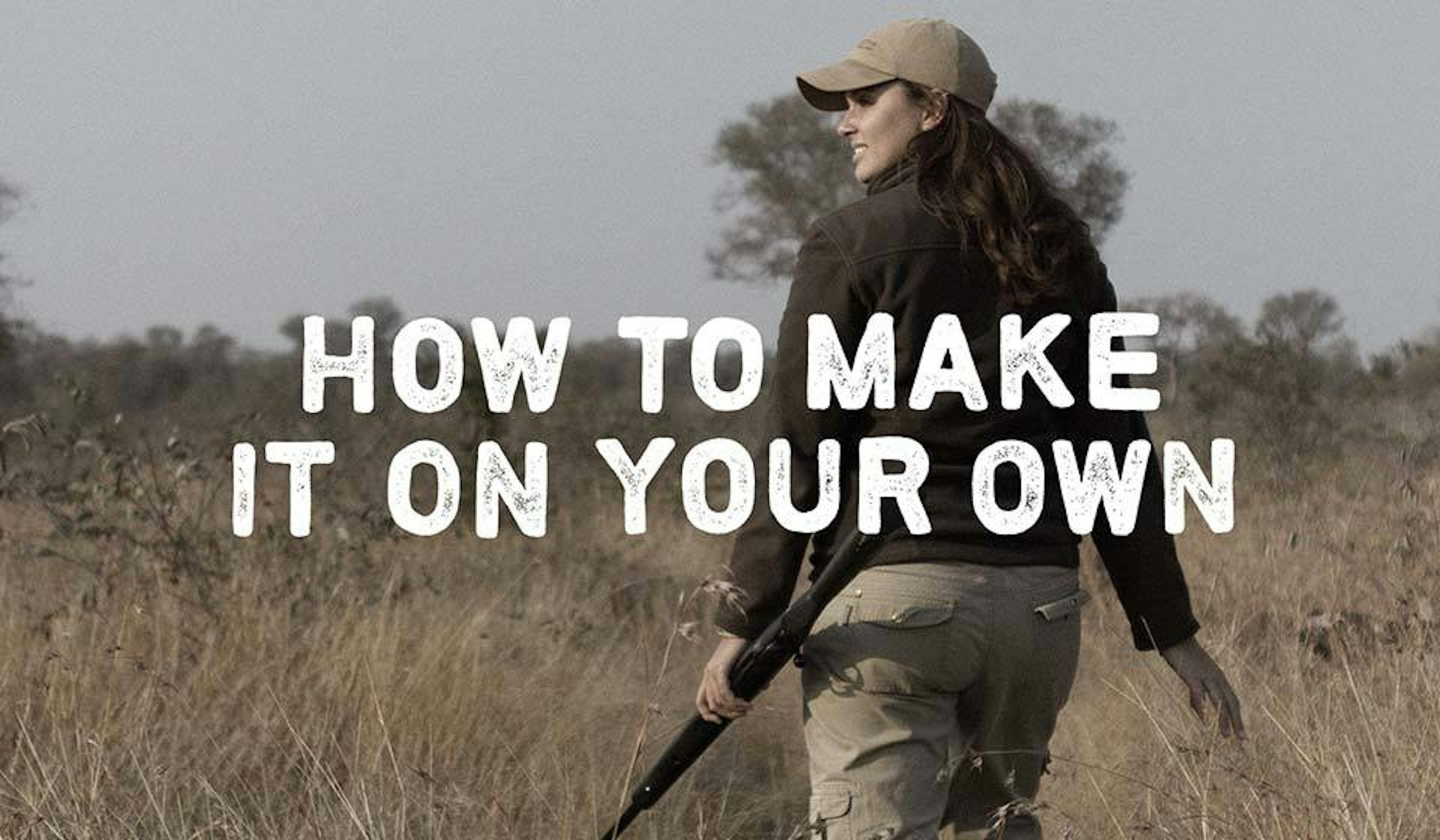

The conservationist who fled Hollywood to save rhinos in the African Bush

- Text by Adam White

- Photography by Our Horn is NOT Medicine

Whenever she visited the lush safari paradise of South Africa’s Kruger National Park with her family as a teen, Lee-Anne Davis militantly protested ever leaving. “We’d drive all the way from Cape Town in our Kombi and spend the week, and I’d always go back kicking and screaming because I wanted to stay,” she recalls today. “That’s where I learned to love the Bush.” But it wasn’t until she was 30 years old that she finally decided to make it home.

Before that, a life in Hollywood was on the cards. “I was acting in commercials and doing modelling work, while working at the Chateau Marmont.” She laughs at the memory of moonlighting as an aspiring actor while cleaning up after celebs. “It was obviously a very different life to the one I lead now.” Swapping billboards on Sunset Boulevard for packing heat in the African Bush, today Lee-Anne is a game-ranger and rhino conservationist with her own charity, Our Horn Is NOT Medicine. A world away from the land of rampant, starry-eyed ambition.

Taking such a radical leap into the unknown was traumatic. “I actually broke out in shingles and very unusually I lost the vision in my left eye. I just had a cornea transplant in March and so far I’ve got fifty per cent of my vision back. But it just tells you how difficult the situation was.”

A big part of the difficulty was how much of her game-ranging dreams were caught up in fantasy. Knowledge of the realities of the profession eluded her. “I had absolutely no contacts. I knew nothing. I didn’t know how much money game rangers made, where they lived and slept. Do they live in a house? How do they wash their clothes? I had absolutely no idea.”

And it didn’t get any easier when she got there. After signing up to one of the largest game-ranging courses in South Africa, Lee-Anne jumped headfirst into six months of intensive training, covering everything from a physical boot camp to the fundamentals of science and botany. “It’s very much a male-dominated world, and I felt our trainers were a little harder on [the women], just to prepare us for what they thought we would struggle with.”

Out of 25 recruits, Lee-Anne was one of only three women – and one of those dropped out after a week. “I think my age helped me a lot, because at 30 I was quite old to start becoming a game ranger. Most of the guys on the course were 22 or 23, just out of university, and they were into having these nice two-year stints in the Bush. For me, this meant a career. This was my life.”

Lee-Anne credits her success as a game ranger to her own vulnerability, and her openness to being emotionally touched by the nature surrounding her. The tourists she helps guide through the Bush can’t help but then reciprocate. “I often have guests email me once they get home,” she says, “and they say, ‘I’ve just seen some geese on my lawn, and I’ve been watching them for an hour.’ And I’m so into that, getting people to open up.”

She admits, however, that all the emotionally charged human interaction of the job came at first as a surprise. “I kind of wanted to be away from people a little bit,” she laughs. “But I’m more social now than I’ve ever been in my whole life. I drive every single day for seven weeks at a time, and my vehicle is always full of guests and you get to know them very well. They start talking to you about their lives.”

She says that many of her guests open up, confiding in her their personal traumas and occasionally meaningful reasons for travelling. “I never, ever saw that coming. I didn’t realise that I was basically going to become their psychologist.”

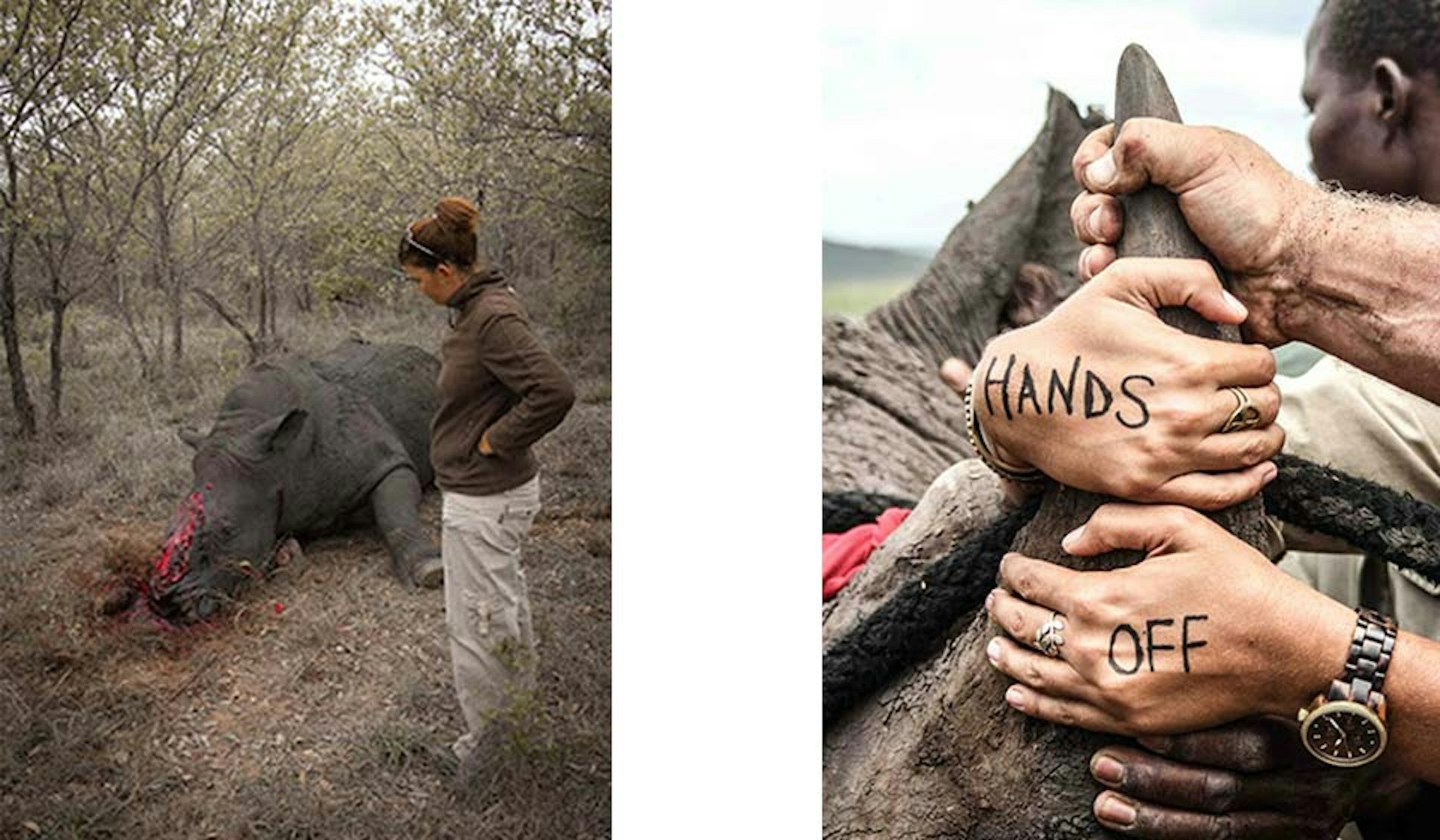

But while her day job keeps her occupied in the field, her true passion is conservation. In early 2012, Lee-Anne founded Our Horn Is Not Medicine, a charity devoted to protecting South Africa’s endangered rhino population. Through education and conservation, they aim to curb the systematic slaughter of rhinos for their horn – much of which is then shipped to Asia, where the horn is believed to hold healing properties.

Rhinos can survive without their horn, but most poachers use a knife to painfully hack away at the animal and completely extract the horn, killing the rhino in the process. Many conservationists are currently arguing for a taxed trade on rhino horn, both to prevent money falling into the wrong hands, and to sustain the rhino population.

Just one kilogram of rhino horn can be sold for as much as $65k on the black market. When horns can weigh up to 7 kilograms, it means poachers can earn up to half a million from one rhino – that’s more than both cocaine and gold. “You’ve got these animals walking around with gold on their faces,” Lee-Anne argues. “On the other side of the fence you’ve got a poor dude with seven children and he can’t get a job and he can’t feed them. What do you expect?”

“Sometimes I do spend my nights staring at the ceiling just thinking, ‘How the hell am I going to get this right? How am I going to save these rhinos?’ But if you have that fuel, you’ll never stop. You’ll just keep going, and you’ll do everything in your power to make a difference. I think a lot of people are afraid that they can’t deal with all the pain and the cruelty. But it’s happening regardless of whether you’ve turned your back or whether you’re looking.”

HOW TO TURN YOUR PASSION FOR CONSERVATION INTO REAL ACTION

Keep the love alive

“A friend of mine in LA said to me, ‘Love comes and goes but passion lasts forever.’ I thought about that quite a lot, and I still do. What it’s taught me is that if you are in love with something, or if you do something that you’re passionate about, and you love it and it just becomes your world, nothing else matters. That is something that no one will ever take away from you.”

Stand by your cause

“It’s very important to have a cause. Everyone should have a cause, because everyone has something that they are passionate about. And I always believe you have to stand by that. You might not feel like you’re making a difference, but you are.”

Target your frustration at something more than ‘clicks’

“People just comment on Facebook and Instagram and think that’s going to make a difference – that’s not going to help. Angle your anger, and put it into a place that’s going to do good.”

Rally your friends

“Instead of asking for birthday presents, ask everybody to donate £50 and send it to us. When you send it to us, I’m going to buy a bulletproof vest, because I need to buy six bulletproof vests, and then I’ll send them a photo of the bulletproof vests that they themselves have bought. And that makes people feel great.”

Get on the right side of history

“Conservation’s biggest problem will be people who have just sat on their hands and watched it all unfold without ever doing anything about it. If you just stand by and let it happen, it will probably be the biggest downfall that our wilderness will ever see.”

Find our more about Lee-Anne’s work at Our Horn Is NOT Medicine.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.