How coverage of the Tory conference showed me the ugly face of British media

- Text by Fiorella Lecoutteux

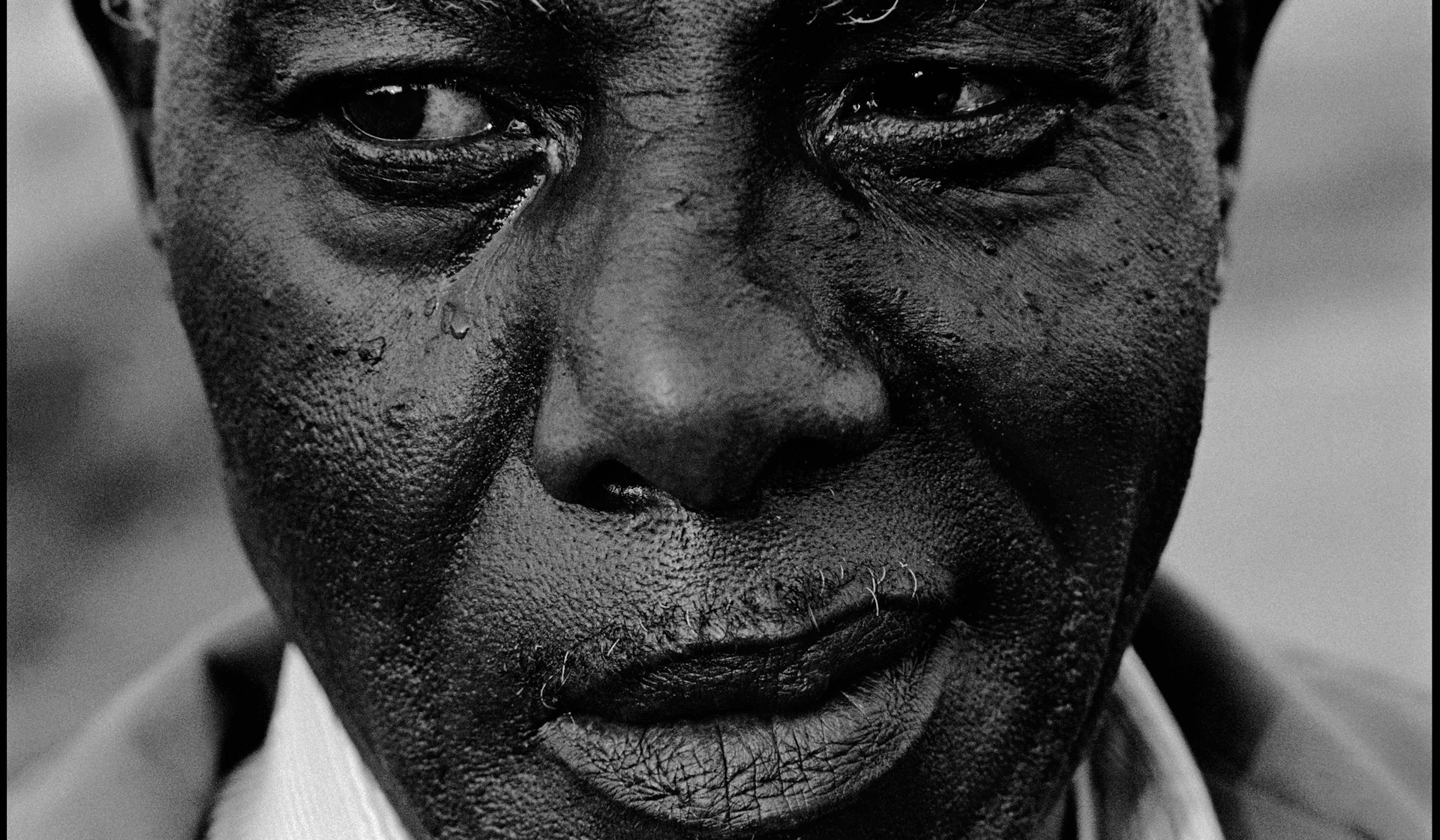

- Photography by Richard Searle

“We are] the party of working people, the party for working people – today, tomorrow, always.” So began David Cameron’s speech at the annual Conservative party conference in Manchester last week. Set to themes like immigration – or anti-immigration for home secretary Theresa May – the conference was a highly media-managed event. But outside on the streets, the People’s Assembly Against Austerity planned a week of action to ‘take back Manchester.’ Organized protests, workshops and talks were scheduled as an alternative to the austerity narrative. When the Tories discussed the controversial trade union bill – a measure threatening to restrict the right to strike legally – trade unionists had a platform just a few blocks away to express their discontent.

On Monday October 5, I was in the city centre surrounded by thousands of Mancunians and visitors from across the country as Jeremy Corbyn took to the stage outside Manchester Cathedral. “They think the only show in town is austerity! They think the only show in town is cutting our public services!” he said to a volley of applause. But the biggest show in town by far came from the protestors themselves, 80,000 of whom peacefully marched through Manchester against more austerity cuts on Sunday. This challenge to Tory rule, “has suddenly made people talk amongst themselves – people are now more excited about the kind of world that we could live in,” Corbyn said, and renewed a determination not to let the Tories define the terms of the debate.

But open the papers or turn on the news, and the media coverage couldn’t have been more different. Popular press like The Sun, Daily Mail and The Guardian published entire spreads on the Tory conference, but failed to report on the mood on the street. Lengthy articles appeared on Theresa May’s upcoming speech on immigration with very little analysis – largely lifted straight from press releases.

What little coverage appeared of the Tory opposition was always in vilifying, derogatory terms. When The Sun reported Corbyn’s speech, it boiled it down to a small headline entitled ‘gatecrasher Corbyn rant.’ The short paragraph that followed intimated that Corbyn was ‘inciting violent protests’ by turning up at the rally. This is not far from Cameron’s own party speech that warned Tory members from ‘terrorist-sympathising and Britain-hating’ Jeremy Corbyn.

The Telegraph didn’t miss the opportunity to describe the opposition rallies as ‘hate-filled protests.’ Their reporter cast an infamous incident where Tory delegates were spat at as the real face of Corbyn’s ‘new politics.’ He argued the week of protests were clearly engineered to put conference attendees under threat of being ‘punched at, spat at, kicked, and subjected to racist abuse, sexist abuse and other general threats of violence.’

The focus on isolated events of violence while ignoring the peaceful and largely good-natured protest by 80,000 people raises important questions about how the media chooses to portray major political events. What is present and what is absent in the news tells us a lot about the media’s affiliations. To understand why the media privileges certain perspectives over others, it is crucial to identify the politics that underlie each media outlet – and their ownership says a great deal.

Today, there are five billionaires who own over 80% of the UK’s national newspapers. You might recognize some of their names: Rupert Murdoch (The Sun, The Times, Sky News), Richard Desmond (Daily Express, Daily Star, Channel Five, OK!) and Lord Rothermere (Daily Mail, Metro). Not only do they own a lot of newspapers, they also have the biggest readership according to the National Readership Survey, both online and in print. As for television news, even the BBC, which is supposed to remain impartial, is often swayed by the direction taken by the print press. In the case of the Manchester protests, much of the reporting was focussed on the Tory member who got an egg thrown in his face.

The Leveson Enquiry – a judicial public enquiry into the practices and ethics of the British media launched in the wake of the phone hacking scandal – has pointed to the connections between the media moguls and the government in power. Collusion between media and political power can come in many forms, and isn’t always as obvious as Rupert Murdoch’s private lunch with Thatcher in the eighties or meetings with David Cameron before the last elections.

When the establishment and corporate media are so often ‘on-message’ with one another, it’s a sign the UK lacks a truly objective media that is willing to speak truth to power. Media Reform UK has further stressed how these same media outlets backed the invasion of Iraq in 2003. And it comes as no surprise to learn that The Daily Mail is controlled through an offshore trust and its owner Lord Rothermere is domiciled for tax purposes outside the UK, despite residing at Ferne Park, a stately home in Wiltshire. These are just a few examples that reveal the connections between the media, its owners, political influence and money.

Beyond shaping the news, the UK mediascape has a critical role in society’s larger structures of power. If we are to accept their narrative, last week’s protests in Manchester were either violent ‘fascism’ against the Tories or just did not appear on their radar.

The UK media is in dire need of reform to make sure that all voices in our society are heard – not just those that agree with the government and their policies, which benefit powerful and wealthy interests. To enjoy a properly functioning democracy, we need more transparency and more plurality. We need a media that doesn’t ignore the mood on the street.

These are just some of the issues to be addressed at the Media Democracy Festival, Saturday October 17 at Goldsmiths University, London. Open to all, the programme of talks, film screenings and workshops will attempt to answer a complex but crucial question: how can we achieve a media democracy?