Dan Draisin

- Text by Jon Coen

- Photography by Henry Zucker

Was there ever a bigger YouTube sensation than the Arab Spring? In the age of the status update, we all have the power to instantaneously call shit on the manifold injustices plaguing our world: the Occupy Movement grew 140 characters at a time; outraged British students mobilise via BBM; in the space of a few hours, a national protest can be organised via text message, captured on an iPhone and uploaded onto Tumblr – all before dark. And yet, fifty years ago, capturing real-world street politics on film was as unheard-of as the World Wide Web. But that didn’t stop one young man from doing just that.

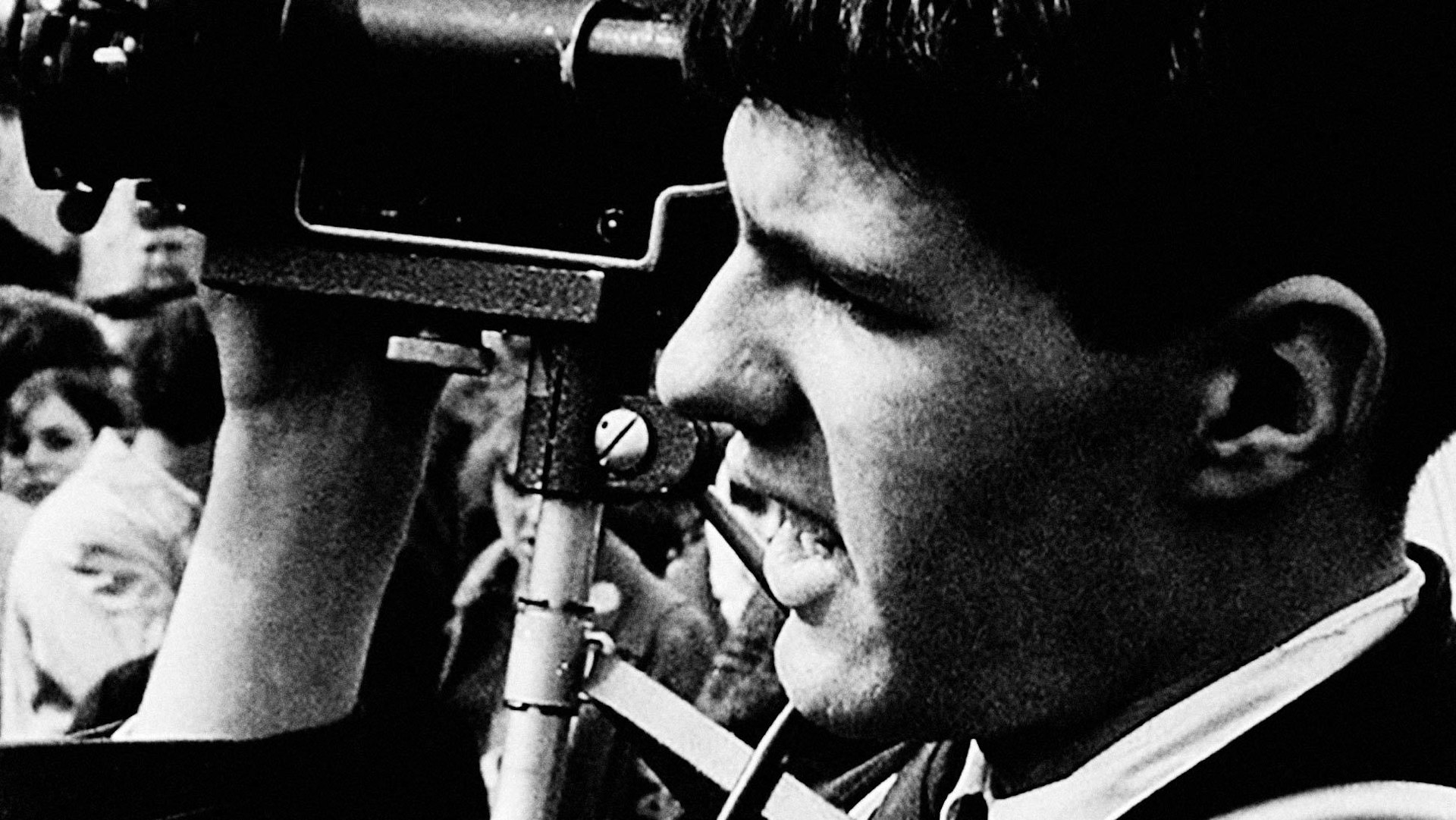

In 1961, Dan Drasin was just an eighteen-year-old kid from Brooklyn intrigued by the countercultural scene percolating around Greenwich Village. But on Sunday, April 9, his role in history took a sudden turn when a protest in Washington Square Park turned into a confrontation with the NYC police. What started out as a simple demonstration by a group of folk musicians – frustrated by the fact that their application for a permit to play music in the park had been denied – descended into a torrent of physical arrests. And, armed with a 16mm camera, Drasin captured the whole thing on film.

The Washington Square Park ‘Beatnik Riot’ became a landmark of the Beat movement, which begat many of the sweeping social changes of the 1960s. On the surface, they were just a crowd of young people lobbying to play music in a public space, against a city that saw them as undesirables. But the seed planted by those unwitting, young activists grew into a generational struggle to address social issues across the board.

The scenes captured that afternoon live on today as DIY documentary Sunday – a seventeen-minute black-and-white film that invites the viewer to join Drasin on the frontline as musicians, writers, artists and activists debate their rights, confront police, and eventually join hands in solidarity until they’re removed by sheer force. Even without a Facebook feed, the doc became popular at film festivals throughout the 1960s and allowed the newly politicised Beats to spread their message far and wide.

A few years ago, Sunday was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive due to its historical significance – but the importance of its content never passed Drasin by. Even as a young man, he had the foresight to document the history bubbling up around him, as so many of us do today without a second thought.

Were you involved in the counterculture before that fateful Sunday in 1961?

I wasn’t really. I grew up in the 1940s and 1950s and came out of a fairly straight background. It wasn’t until my late teens when I started hanging out in Greenwich Village that I became involved in the counterculture. It was mainly through the folk music scene, which some friends I’d grown up with got me into. When I went off on my own and moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan, I found myself living in an apartment over Izzy Young’s Folklore Center on Macdougal Street in the Village in 1960 and 1961. I had a friend across the way in a shabby apartment building whose wife had a talent for singing. She’d found these two guys to play guitars, and they’d come over to my place to record practice tapes. Shortly after that they adopted the name Peter, Paul and Mary.

So on the day of the Washington Square Park Riot, you didn’t go there thinking you were going to film something that would become historic?

No one knew exactly what was going to happen. I knew that a protest was going to take place because the Folklore Center had announced it. At the time, I was working my first film job with Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and Albert Maysles, who were pioneering a new form of documentary filmmaking called Cinéma Vérité. They were developing their own highly portable cameras and sound equipment because until then film technology was clumsy and didn’t allow you to shoot run-and-gun style.

As luck would have it, I was in charge of their equipment room, and their policy was that this rare and expensive equipment, when not in use, could be used by employees for their own projects. I couldn’t afford to buy film, so I raided the company refrigerator for short ends of outdated raw stock, and that’s what I shot the film on. Processing and editing the film cost me all the money I had in the world – $750! But I knew that it would be well appreciated, and it was. It was picked up by a producer/distributor who promoted it to a lot of festivals. It went on to win nine international awards. Who knew?

With hindsight, do you feel like the scenes you witnessed that day were a turning point in our countercultural history?

Looking back, it’s clear that the Washington Square Riot was one of many events and people that, together, were launching a new cultural and political awareness that would soon spread to the rest of the country and to some extent the world. But to be honest, at that time – early 1961 – we were barely out of the 1950s and had no concept of a countercultural revolution. We were just doing what we thought was right.

Looking back, it feels right to draw a line between the Beat Generation and the countercultures that followed in their wake, many of which became more overtly political over time – from hippies protesting the Vietnam War to Riot Grrrls chanting for women’s rights. But it seems that a lot of the more prevalent Beat writing was much more indulgent than conscious…

That’s a great point. As idiosyncratic and emotional and unconscious as it may have been, it was still a huge leap out of the grip of the 1950s consciousness. The culture of America in the 1950s was largely moulded by the Second World War. As a legacy of so many people’s military experience, things tended to be somewhat hierarchical. At the same time we were simply tired of war – we needed “peace and prosperity”, which was a common political slogan. The nation needed to settle down to an ordinary life. The downside of that was that it became a very shallow and conformist culture. The Beats began to corrosively undermine that, quite invisibly at first, and created a cultural oasis for people who just were not temperamentally suited to 1950s culture. The older Beats actually looked down on the upstart ‘beatniks’ and hippies of the sixties and seventies as kind of a watered down version of themselves. But the younger ones wound up having the political impact, which the Beats didn’t.

So how did the Beat movement usher in the more political ‘Flower Power’ generation?

Well, I sort of see them as all of a piece. The so-called ‘Flower Power’ era seemed to me to be more of a natural outgrowth of the Beats. I don’t see a clear line of demarcation. Generally speaking, the East Coast movement was more rigorous, traditional and reactive. People were more into fighting and exposing the old way for what it was. On the West Coast things were more relaxed – maybe less intellectually rigorous, but more adventuresome, exploratory, forward-looking, more ecologically aware and a little less urban-oriented. It was still a direct outgrowth of dissatisfaction for the old ways, but it was more oriented toward building a new future. They were two very complementary sides to the same coin.

Do you see any parallels between the youth-led activism you witnessed in the sixties and protest culture today – specifically, the Occupy Movement and Arab Spring?

Well, the parallels are pretty obvious. Dissatisfaction with the status quo runs in cycles, and of course each generation has its own particular issues. But it largely comes down to the question of hierarchy vs. democracy. We’re a little more sophisticated now and we understand more of the psychology of power, but there are specifics that each generation has to learn on their own. And that’s not entirely a bad thing.

You’ve been involved in a lot of different creative media in your work. Why do you think that artists are always the one to drive social change?

Well, I think it’s by definition. Creatives imply creativity, which implies newness, the willingness to explore, the willingness to break boundaries. It’s an important form of leadership, to be willing to risk and willing to say and do things that may be uncomfortable to one’s peers. Speaking of which, there are things going on in the realm of science now that are going to shake things up very, very seriously over the next few years and lead to a completely different view of reality as a whole. A generation or two from now, reality will have a very different feeling to it.

Do you take any notice of countercultural movements today – like the more overtly political hip hop and punk scenes?

I’m an old fart now, so the pop music and pop culture of recent decades have largely passed me by [laughs]. Like all cultural movements these are transient, and will come and go. But the rap and punk cultures, to name only two, are certainly profound expressions of dissatisfaction. That expression is an inevitable phase. The problem is that dissatisfaction in and of itself goes nowhere. You have to have a trajectory. But it all runs in cycles. The protest comes first and then the new developments appear. Then the next generation just grows up with them and thinks that they’re normal. You can see that in some of the alternative language and ideas of the 1960s and 1970s, which have become very well absorbed, almost invisibly, into the mainstream culture. Maybe that’s how it has to work.