Inside the fight to save creative freedom

- Text by Chris Hayes

- Illustrations by Simon Hayes

It’s been said that Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” invented the music video, seven years before MTV came onto screens worldwide. And despite the fact most people know many of the lines off by heart, this peak of the ’70s prog rock genre has notably ambiguous lyrics. In just under six minutes, Freddie Mercury questions the nature of reality, existential despair, and confesses to murder. But the song was written during a major turning point in his life: after a seven-year relationship with a woman, he was embarking on his first proper relationship with a man.

This connection is one that conservative censors have been trying to keep from audiences since the song was released in 1975. When a Greatest Hits tape was released in Iran in 2000, it was accompanied with translations and explanations that omitted this history. Even in 2018, the Malaysian Film Censorship Board cut a whopping 24 minutes from the biopic of the same name: including the scene where Mercury explains to his fiancee, Mary Austin, that he is bisexual. This decision angered Malaysian audiences, and created massive holes in the plot because you can’t tell his history without this part of the story.

This kind of censorship is something many creative projects and people have had to face throughout history – but it can often get overlooked. So who will stand up for artists when they’re silenced, regardless of where they are in the world?

Last year, Freemuse celebrated its 20th anniversary. The organisation, which was founded at the World Conference on Music and Censorship in Copenhagen, initially promised to tackle human rights violations against musicians and composers – but has since expanded to fight for all artists, globally. In the face of constant crisis and the rise of Trump styled autocrats around the world, their fight is a welcome beacon of light.

The threat to artistic freedom comes from “a range of state and non-state perpetrators,” the Executive Director of Freemuse, Srirak Plipat, tells Huck. “This is a ubiquitous problem and one that constantly evolves, which means its constant monitoring is necessary so that governments and other institutions are held to account.”

“Freemuse wants to bring arts and culture into the international human rights conversation and agendas, paving the way for positive change in the fight for universal freedom of artistic expression.”

Their mission isn’t easy. As well as the 24 minutes of LGBTQ scenes that were cut from Bohemian Rhapsody in Malaysia, recent campaigns involved a Tanzanian actress who has been banned from acting and charged with posting sexually explicit content after sharing images on social media, and an exhibition in Hong Kong that was cancelled after ‘threats’ by Chinese authorities. Cultural activities are being stopped because those in power disapprove, and often artists are facing discrimination, jail time and even threats to their safety.

And much of these violations are happening on our doorstep in Europe – and often with a minor, bureaucratic justification. A 14-year-old boy in England was banned from performing a drag act at his school’s end-of-year talent show on July 17 because it was deemed “age inappropriate.” A national theatre director in Belgrade was fired just two days after criticising the reduction in the budget allocation. And the artist Robert Mapplethorpe has been the subject of censorship for decades because his work openly deals with gay themes, which again arose this year in Portugal.

Clearly, the world is providing enough problems to keep them busy – so what can we learn from this 20-year fight for artistic freedom?

*

Freemuse was set up in 1998: the year the affair between Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky became public, Google was founded, and Titanic became the first film to gross $1 billion. It was a few years after the Iron Curtain collapsed, and computers were coming into our lives in a big way. Many people saw the old authoritarian ways of the past were on the way out, and a mixture of liberal politics and technology signalled a bright, open future.

Unfortunately, the 20 years that followed didn’t bring a utopia. A recent Freemuse report on artistic freedom documented 48 artists who were serving combined sentences of more than 188 years in prison. Spain imprisoned 13 rappers under controversial terrorism legislation – more musicians than any other country. Rapper Valtonyc said on his Twitter account that he was “the first musician to enter prison in the Spanish State condemned solely by the lyrics of his songs” – accused by the government of “grave insults to the Crown” and of “glorification of terrorism and humiliation of its victims” for supporting Basque separatism groups. On average, one artist per week in 2017 was prosecuted for expressing themselves. 70 per cent of violations against women artists and audiences were on the grounds of indecency, a rationale used in 15 countries across Europe, North America, Asia and Africa.

Some of the motivations for censorship are familiar – governments or corporations that don’t take criticism well, and weak legislation defending artists rights means that they’re easier to push around. But new challenges have emerged too. Plipat explains how the “ever-increasing digital space” offers greater opportunities for artists, but also “more opportunities for arbitrary censorship – sometimes due to opaque and inconsistent guidelines by social media companies – or nationwide internet blackouts and government social media blackouts to silence opposing voices.”

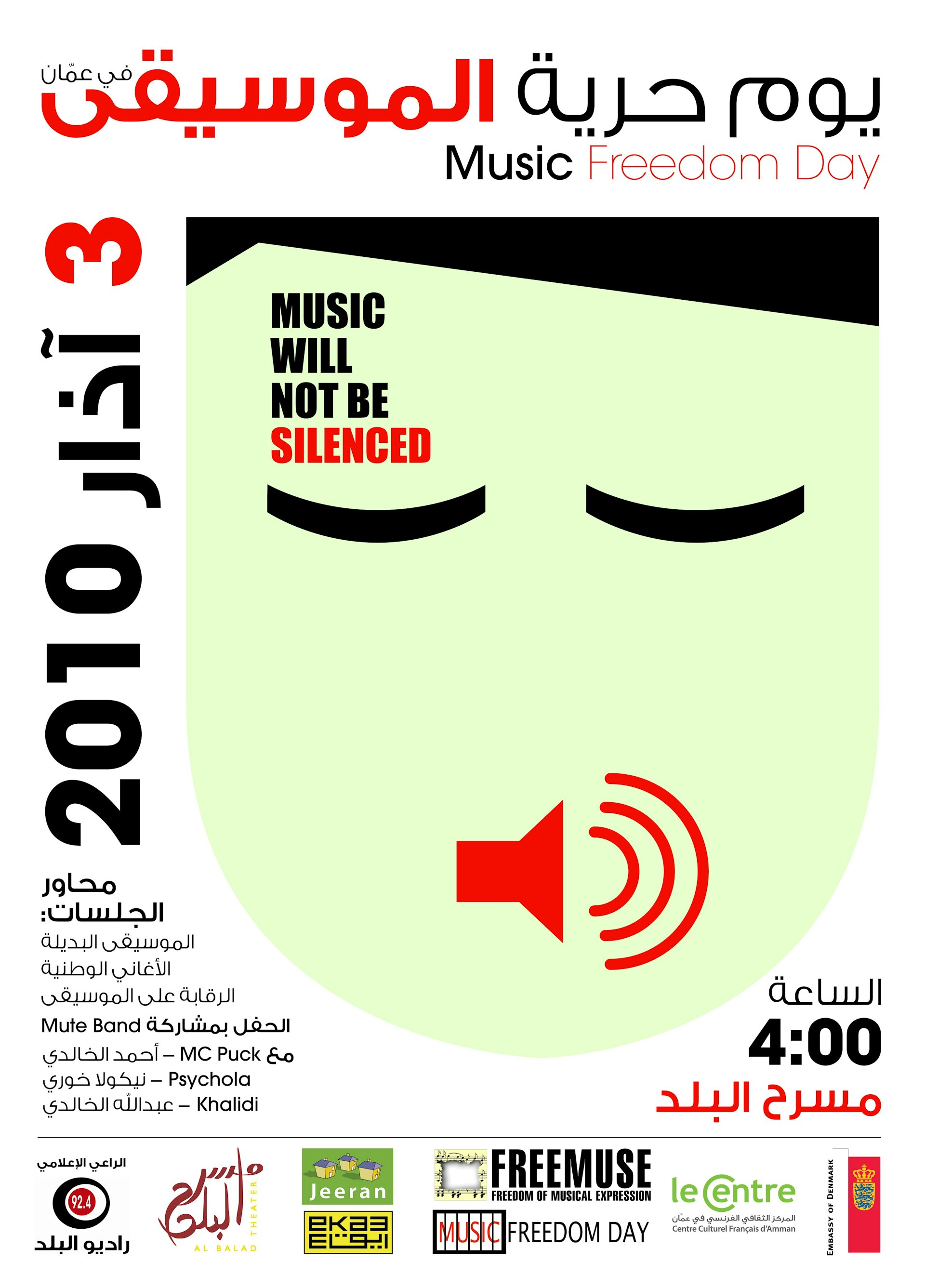

Freemuse’s Music Freedom Day 2010

While certain governments – like Russia or China – are more regularly criticised for curtailing freedom of expression, artists in the West face their own uphill battle from a wide range of challenges. As Plipat explains: “the troubling rise in Europe that we’ve seen in 2017 is attributable to expanding already vague laws that trap artists in its net.”

And Freemuse has the research to back this up. Their State of Artistic Freedom 2018 report shows that in 2017, France and the USA were among the top 10 countries found to have censored the most, and Spain was the top country found to have violated freedom of musical expression.

But there is one unifying factor around the world – women, the LGBTQ community and racial minorities are the groups being disproportionately discriminated against. These threats can be very serious; Plipat describes how “culture is being censored on the grounds of indecency and religion, and artists are being silenced with arrests, prosecution and imprisonment.”

While artistic freedom is not generally seen as an important human right, it goes beyond individuals wanting to express themselves. The Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) was sued by Black and Pink – a non-profit organisation focused on supporting LGBTQ prisoners – for allegedly banning and censoring its correspondence to prisoners. In a statement, UPLC Executive Director Alan Mills said: “Prisoners are extraordinarily isolated. Publications give them a lifeline to the outside world. Almost all prisoners will one day be released, and it does no good to isolate them while they’re inside. Having ties to the outside while in prison is one of the best predictors that someone will not return to prison.”

*

So what can be done? Increasingly, the work of FreeMuse isn’t just bringing awareness to these offences, but developing the research and information to bolster advocacy efforts. (They produce an annual Report on the State of Artistic Freedom and the Advocacy & Campaign Guide, for example.)

“Fighting for artists requires understanding exactly why violations are taking place and who the perpetrators are,” emphasises Plipat. “All violations have deep-seated root causes that need to be addressed.”

A key point on all this work, he says, is the “time, coordination, passion and precision from many different angles and pressure points.” It isn’t a question of government or business overstepping, but powerful public and private interests; “governments, inter-governmental organisations, civil society, artist communities and activists at all levels – local, regional, national and international.”

There is an enormous scale to FreeMuse’s mission – in 2017 alone, they documented over 500 cases of violations of artistic freedom (and, according to Plipat, what they have “documented is just the tip of the iceberg.”)

That said, they’ve already had some notable successes. At the end of last year, after a sustained campaign, a Bangladeshi photographer, Shahidul Alam, was released from prison, arrested originally for supporting student protests under the notorious ICT law. Others they’ve supported include the Equatorial Guinean artist Ramón Esono Ebalé who was jailed for six months on false charges, suspected to have been targeted for his cartoons which are highly critical of the government. But the work of FreeMuse extends beyond individual cases – they are a single source for this kind of research, worldwide. The reports they compile provide an overview that’s useful to governments, institutions and individuals, and they already contribute to important international organisations, like the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review process. It’s not just about raising awareness, but providing the facts and figures that policymakers need so they can act.

With the rise of the far-right, our growing dependency on digital platforms and the ever familiar story of artists struggling to get by, the defence of creative freedom remains an important fight. Freemuse has been doing exactly that for 20 years – this is a human right, that’s under threat from dictators as well as school administrators across the world. And with the growing momentum behind their campaigns, and the increasing level of impact of their research and advocacy, they’re only getting started.

As Plipat tells me, the work of Freemuse “has helped bring arts and culture into the international human rights conversation and agendas, paving the way for positive change in the fight for universal freedom of artistic expression.”

Chris Hayes is an Irish writer in London, and is the Founding Editor of The Emotional Art Magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.