The story behind the UK’s biggest LGBTQ+ helpline

- Text by El Hunt

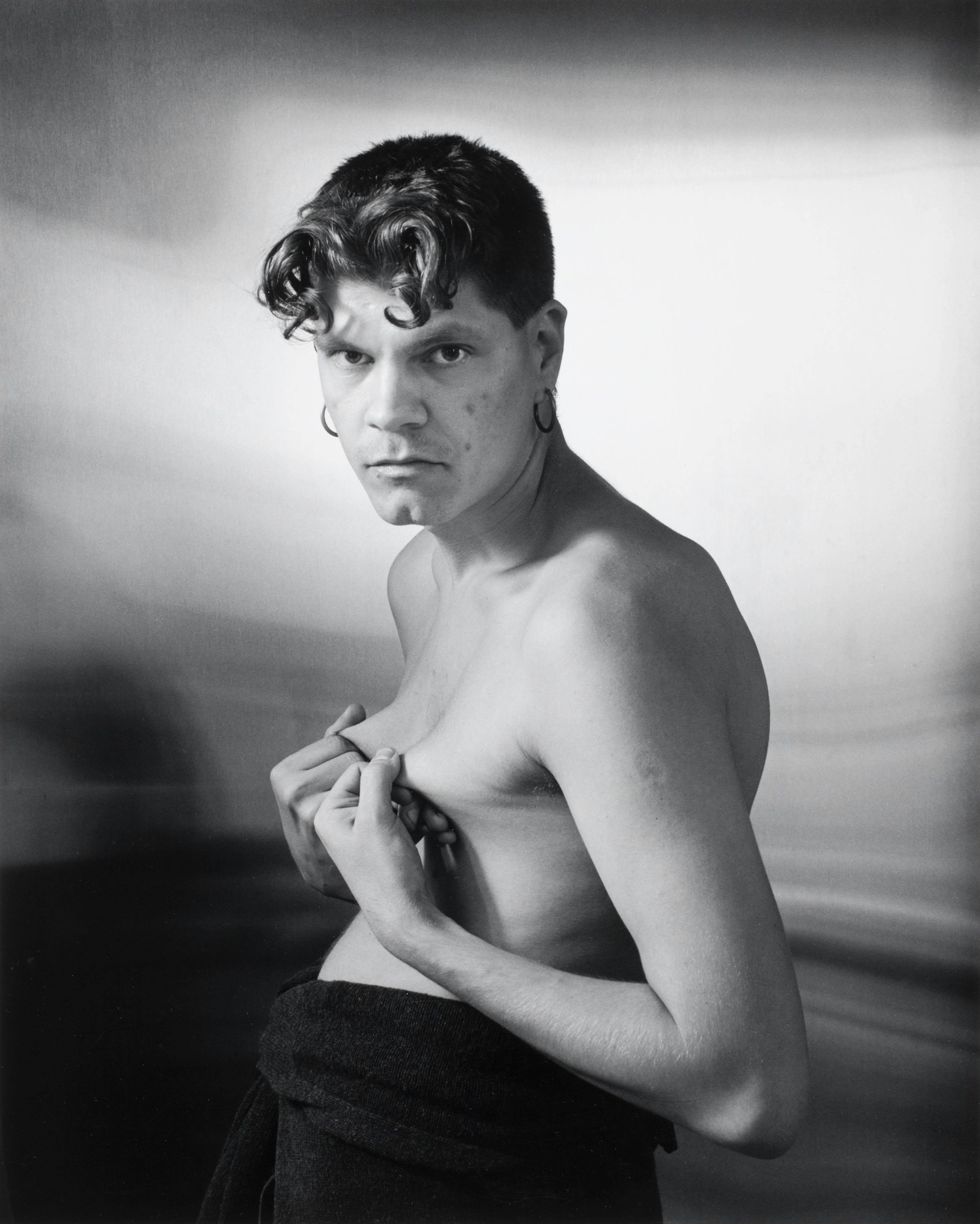

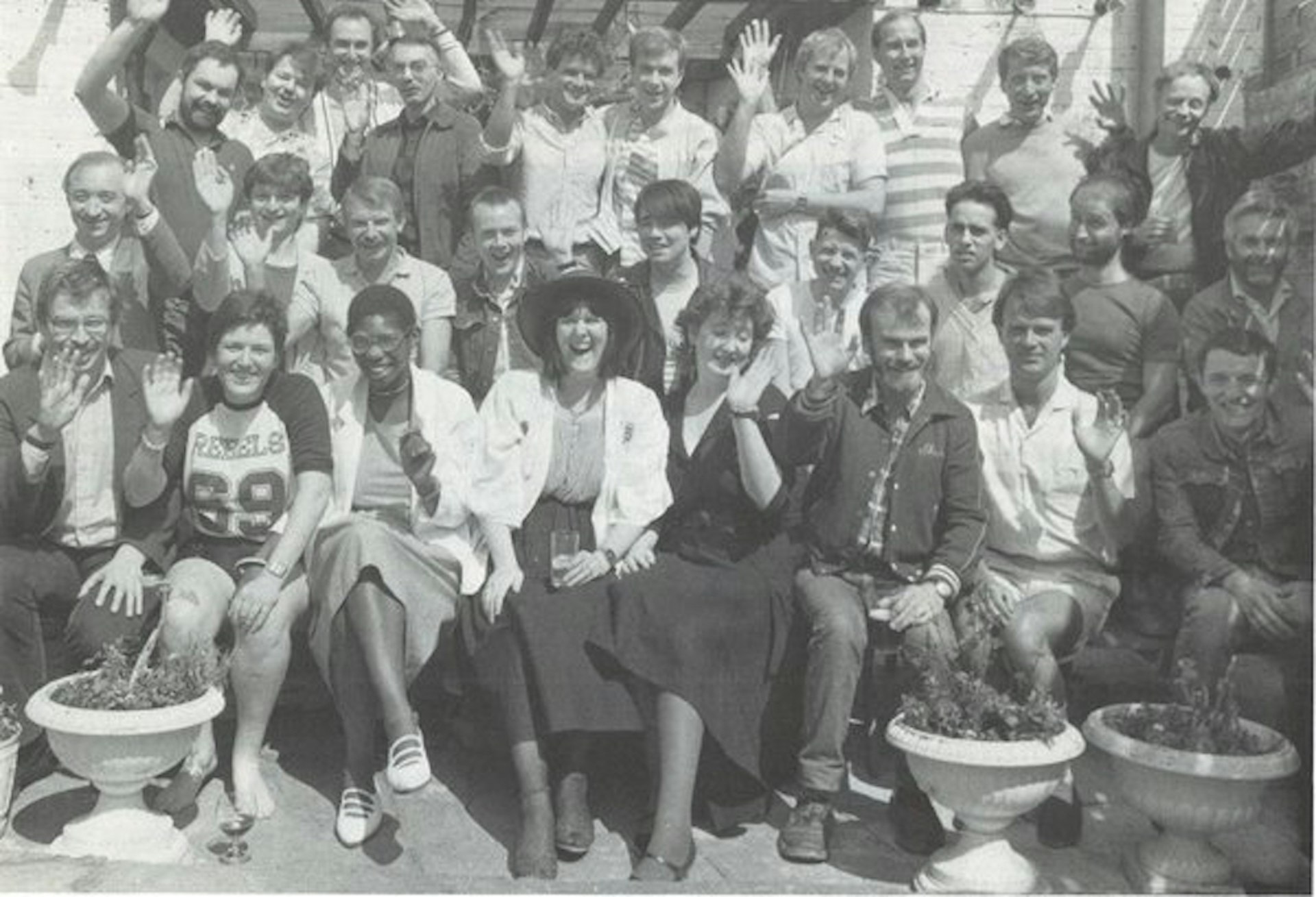

- Photography by Switchboard archives

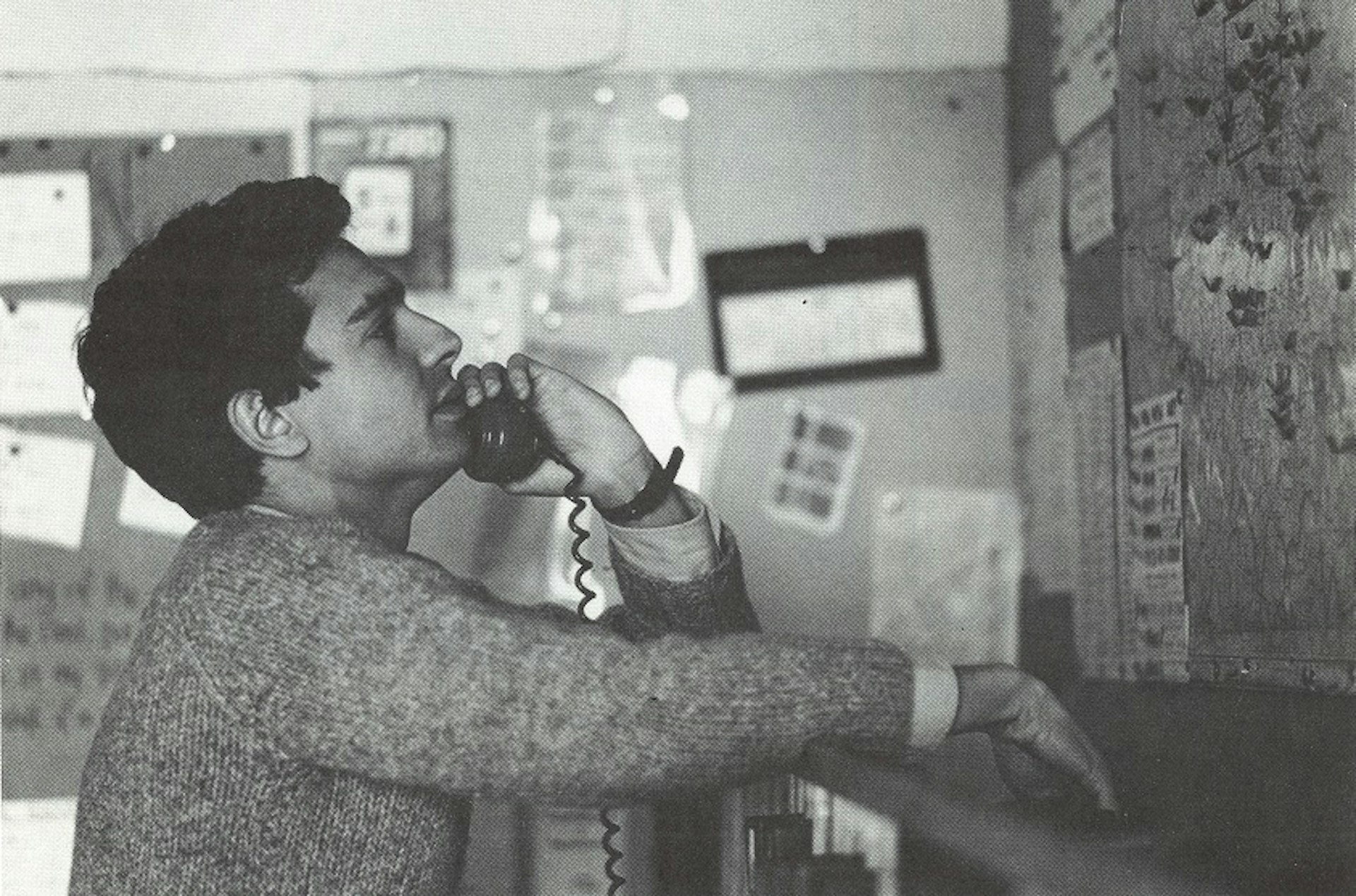

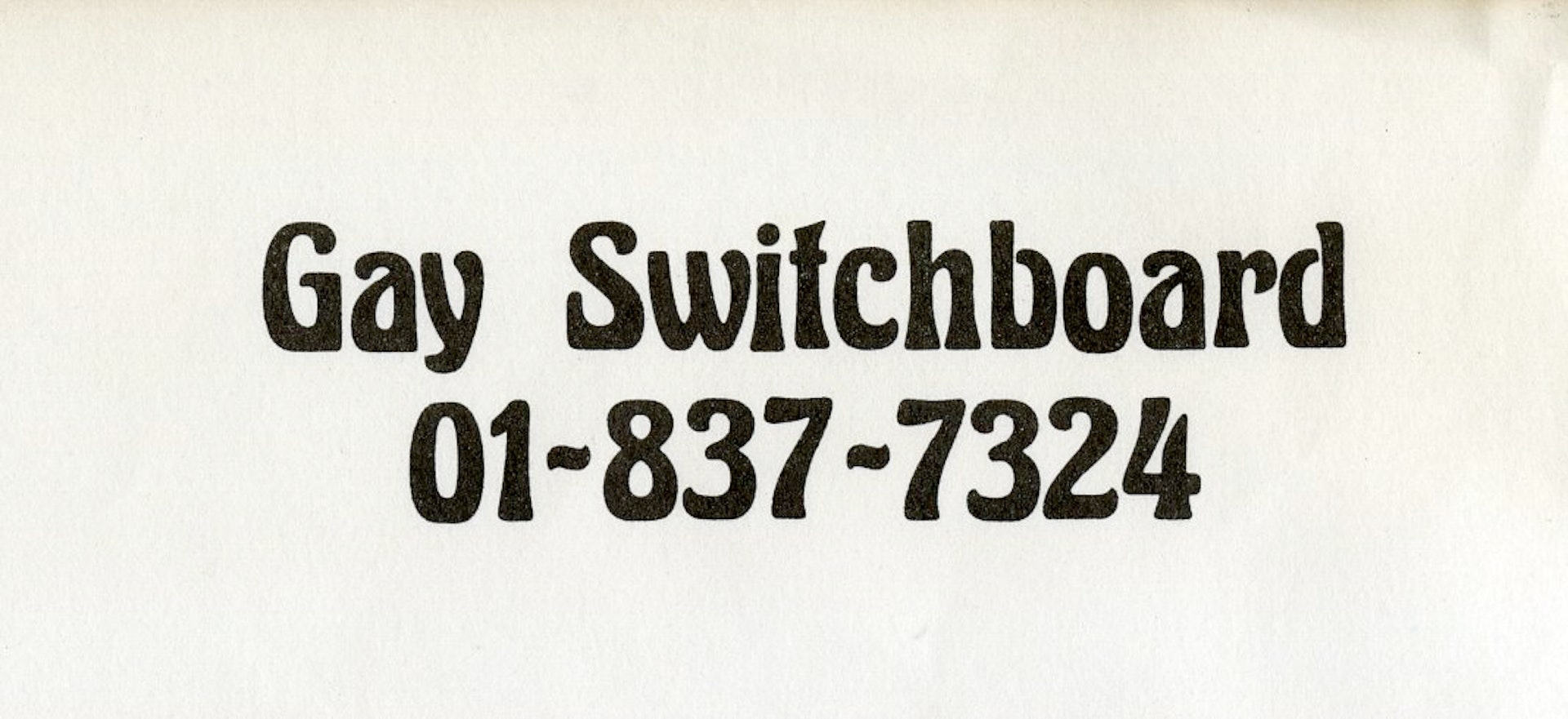

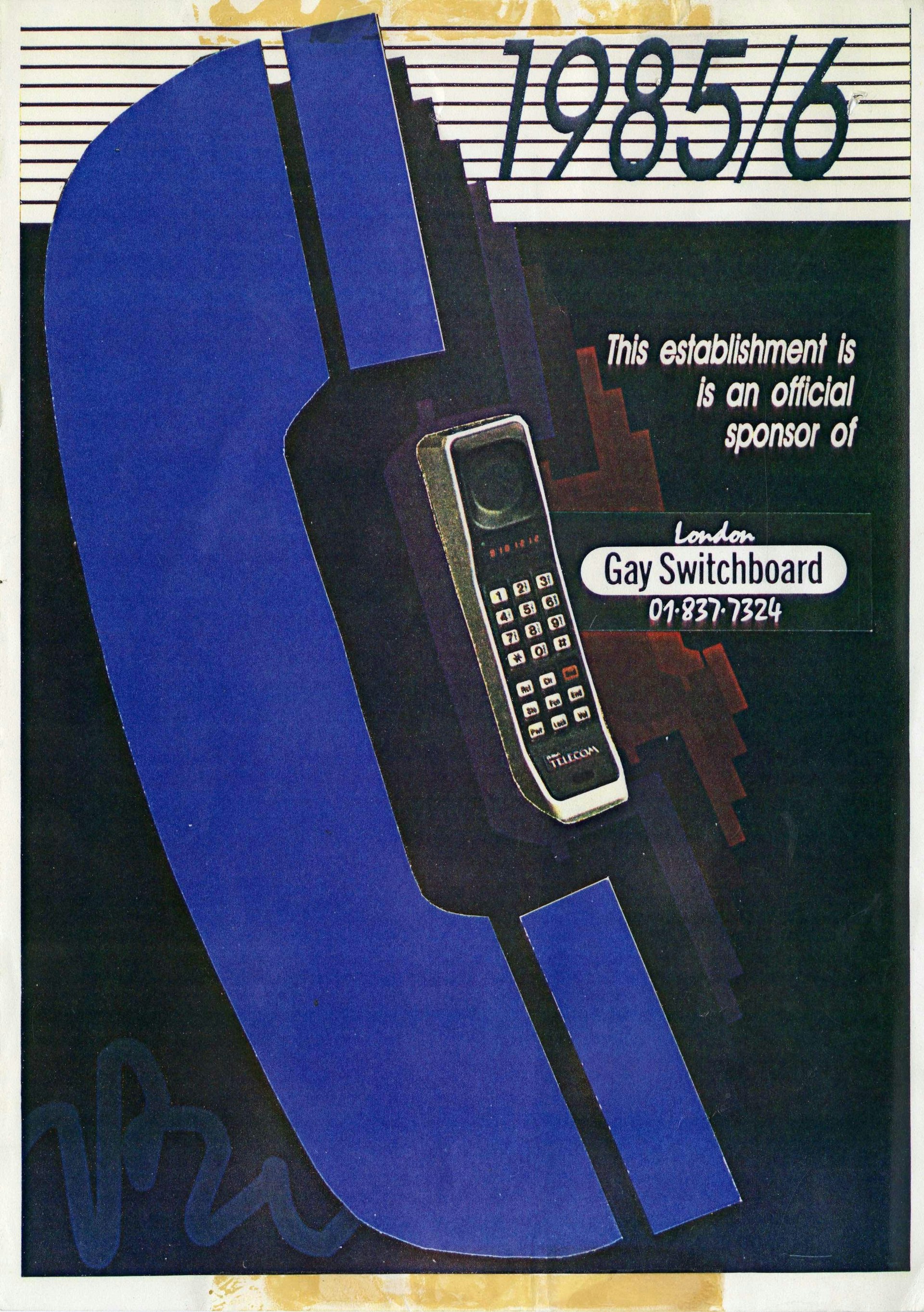

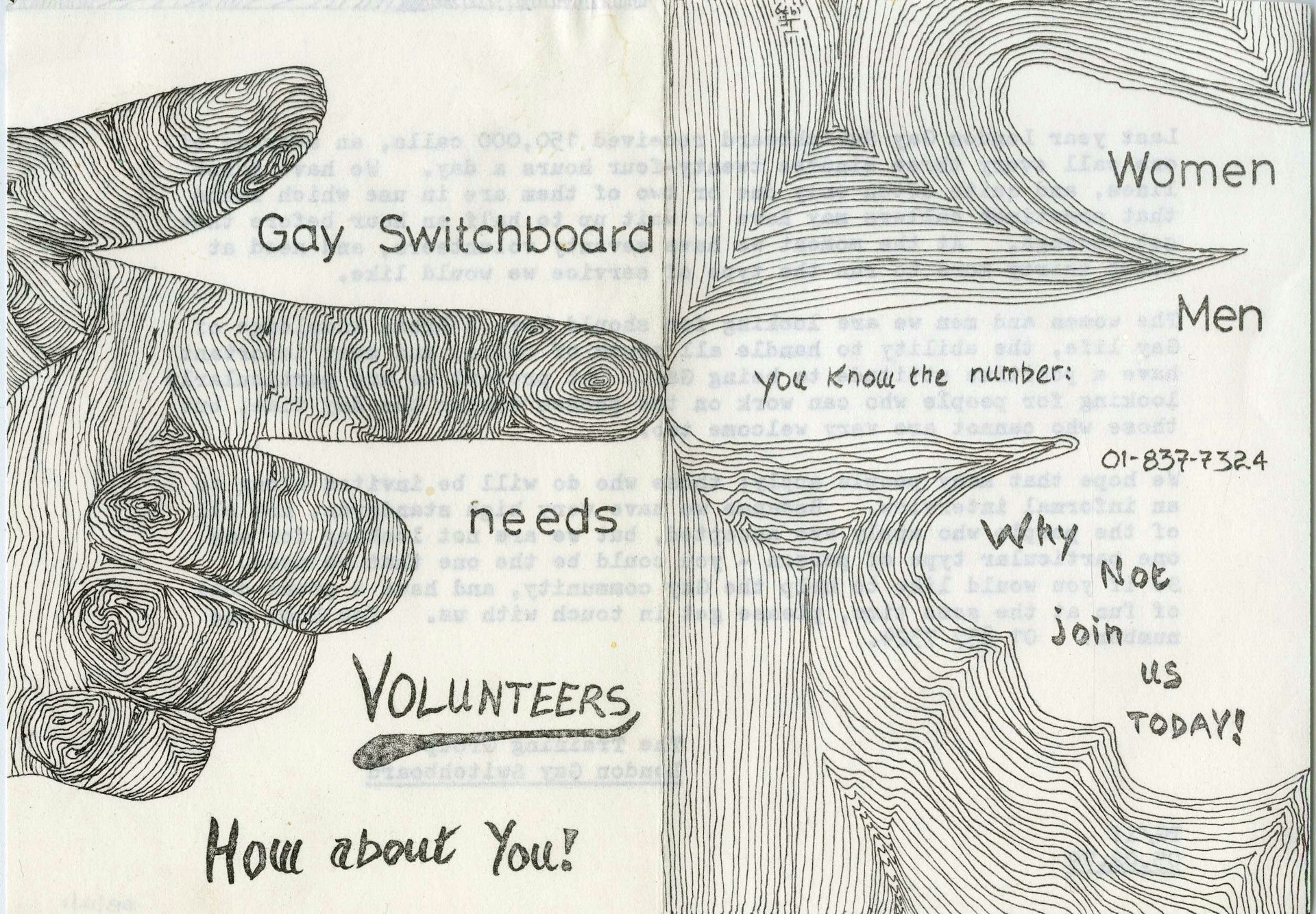

Starting life in a cramped basement underneath London’s Housmans Bookshop, Switchboard answered their very first phone call in March 1974. After taking out a small advert in the fortnightly Gay News newspaper, volunteers at the brand new LGBTQ information and support helpline anticipated about six or seven calls on their first day.

As the evening went on, the phone didn’t stop ringing. An unprecedented 45 people called up the London Gay Switchboard – as it was known back then – during that first five-hour shift. Within six months, the organisation had outgrown the basement, moving upstairs, and installing several more phone lines to meet the immense demand. By 1975, Switchboard was open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

In the years following the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, society remained deeply homophobic, and the LGBTQ+ scene firmly underground. As well as running an accommodation service for finding gay-friendly house-shares, Switchboard advised callers about virtually everything: from legal advice, to what was happening around town.

“Lovely drunk men would ring up because they’d forgotten the Handkerchief Code [a colour-coded system used to indicate preferred sexual fetishes], and they had just picked someone up,” recounts Stonewall co-founder Lisa Power, who started volunteering at Switchboard in 1979. “While he had just nipped off to the loo, they were quickly calling us from the coin box in the corner of the club, to ask us what the other man’s hanky meant.”

“One minute you’d be telling someone where they could meet other lesbians in Leicester, the next, you’d be dealing with someone who had been arrested. Then you’d get some kids in a phone booth having a laugh.’”

“Over the years, there have always been hoax calls, bomb threats and verbal abuse,” adds Switchboard’s co-chair Tash Walker. The helpline even attracts a number of dreaded “wank calls” – and volunteers have tried and tested responses. “With a wank call, you absolutely bring out the long Latin words, the unsexy biological terms, and they just hang up,” Tash says. “If you can imagine a call, we’ve taken it.”

The helpline quickly became the go-to destination for accessing information and support around the clock. As the ’80s rolled around, the AIDS crisis became the most pressing and urgent issue facing the LGBTQ+ community, and Switchboard began constantly collating the most up to date information available.

The deadly illness hit the community hard. Little was known about the disease, and the organisation set up a dedicated line, staffed by specially briefed volunteers, in the days after the BBC aired Killer in the Village in 1983. It was one of the first documentaries to seriously examine the emergence of the disease. “This is a time where people thought you could catch HIV from touching someone,” explains Tash Walker.

“I will always remember the little old lady who was worried that her cat might bite a gay man who had AIDS, and he might give it to the cat,” adds Lisa. “We didn’t know that it was going to kill everyone.”

Switchboard volunteers worked around the clock to support people affected by the epidemic. “We were supporting people who were dying, and people whose family members were dying,’ Tash says. “Switchboard lost many people to AIDS. Our volunteers were grieving as they helped others to grieve.”

“Those first years of the AIDS crisis were incredibly difficult,” says former Terrence Higgins Trust CEO Nick Partridge, who volunteered at Switchboard in the mid-80s. “Until the arrival of effective therapy in 1996, probably one trustee of [Terrence Higgins Trust] would die each year. That made the whole experience very intense, but we were very determined. We were battling on all fronts, with extraordinarily brave feats of both activism and personal courage in the face of a terminal illness. ”

When Switchboard’s phone number was printed on the back of a government-issued leaflet informing people about AIDS and HIV – ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ pamphlets were distributed to every single household in the UK in 1986 – the helpline was inundated. “The phone would ring as soon as you put it down,” remembers Lisa. “If you needed to stop after a call to go to the loo, you had to leave the phone off the hook.”

Around this time, the helpline introduced the practice of talking about safer sex in every phone call. “We were determined to normalise condom use,” Nick says. “Irrespective of the call, we would always finish it with ‘and remember, stay safe, remember to use condoms’.”

And into the ’90s, Switchboard fielded an increasing number of calls from people concerned and angry about Section 28; a cruel policy introduced by the Conservative government in 1988, which outlawed the “promotion of homosexuality” by schools and local authorities. And in the days following the Admiral Duncan nail bombing in Soho in 1999, Switchboard was at the forefront of the immediate response.

Matthew Todd, former Attitude magazine editor and the author of best-selling book Straight Jacket, called up Switchboard as a teenager in 1990. When phoned the helpline, aged 16, he was “on the verge of a nervous breakdown, or maybe killing myself.”

“I was so messed up, because of the messaging in the media,” he says. “Your parents would reject you, or you would end up dead – that’s pretty much what the media was saying.”

“I remember speaking to a flamboyant-sounding man, who called me sweetie, or darling,” Matthew remembers. “I’d never spoken to an out gay person before. To hear someone being warm and relaxed in that respect was a shock. Having someone there to listen was such a stalling experience.”

To this day, Switchboard answers tens of thousands of phone calls each year. Though the internet has made certain services redundant – like the helpline’s accommodation service – LGBTQ+ people continue to call for the same reasons; namely to speak to a friendly, patient listener who understands what they’re going through.

Tash still thinks about a couple of calls in particular; one of them from a young gay Muslim man who rang up, sobbing: “At the end, he just said, ‘I’m due to get married. I’m going to be unhappy for the rest of my life’. He said goodbye, and that was the end,” she recalls.

“You put the phone down, and you just have no idea what will happen next. There was a trans person who had been to their doctor, and had come up against barrier after barrier. It was heartbreaking to hear someone just understanding who they are, and really struggling to get that recognition.”

Nick remembers, above everything else, the intense feeling of relief when a frightened caller summoned the courage to begin the conversation: “I remember calls that were silent to begin with, and you’d stay on the line and say ‘I’m still here’. The release when people began to talk – it would maybe be the first time that somebody had spoken to anyone else about the struggles they were having with their sexuality. Almost immediately, they felt so much better.”

Follow El Hunt on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.