Is virtual reality the new frontier for human rights filmmakers?

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by We Who Remain

You hear the roar of planes flying overhead, then an explosion that shakes the ground you’re standing on. You can’t see above the edge of the cramped foxhole you’re hiding in, but you can feel that was too close for comfort. You look around and in every direction you see the terrified faces of children crouching next to you. There’s nothing you can do, you can’t move, you’re trapped and vulnerable – just like everyone else.

This is a scene from We Who Remain, a groundbreaking piece of virtual reality journalism that puts you in the centre of a little-known active conflict zone in Sudan’s Nuba mountains, where rebel fighters and civilians face a deadly stream of attacks by government forces. Directed by Trevor Snapp and Sam Wolson, We Who Remain is one of the powerful activist and human rights films in the virtual reality strand at the 58th Thessaloniki International Film Festival in Northern Greece.

Socially-engaged filmmakers are increasingly turning to VR to help them force issues into the public consciousness which have gone ignored or under-reported in the mainstream media; from highlighting conflicts in forgotten parts of the world to refocusing attention on humanitarian challenges, like the refugee crisis. In the era of passive news feed grazing and fake news, the 360-degree, sensory and immersive experience of VR is hailed as an ‘empathy builder’ that can break through our chronically short attention spans. But as the novelty of the technology wears off, can VR remain a powerful tool to connect audiences to crucial issues?

Over 4,000 bombs have been dropped in civilian areas in the Nuba mountains since April 2012 and the region is cut off from the outside world, with no humanitarian access. This hidden war shows no sign of ending, yet because journalism has been banned for decades, it receives almost no media coverage. “It’s a place nobody is going to go, it could just disappear,” Trevor explains. “It’s a simmering low-level conflict that’s displacing people, terrorising communities and periodically erupting in violence. But it’s a story that’s just not going to stay in the headlines. After working in the area for many years, shooting We Who Remain in VR was an attempt to break through that and take people to a place they couldn’t go.”

But is VR a better way to highlight the conflict to audiences than conventional journalism, photography or filmmaking? Both Trevor and Sam come from a photojournalism background and argue that VR really is a game-changer. “As photographers, we often felt forced into a box and there must be more effective ways to tell pressing stories,” Sam says. “You can’t communicate what it feels like to be hiding out in a cave or riding on a truck with a mobile rebel unit through photography, or even film. But VR makes you feel like you’re in those places and gives you the freedom to experience those moments in your own way. It’s powerful and immersive in a way that photography isn’t.”

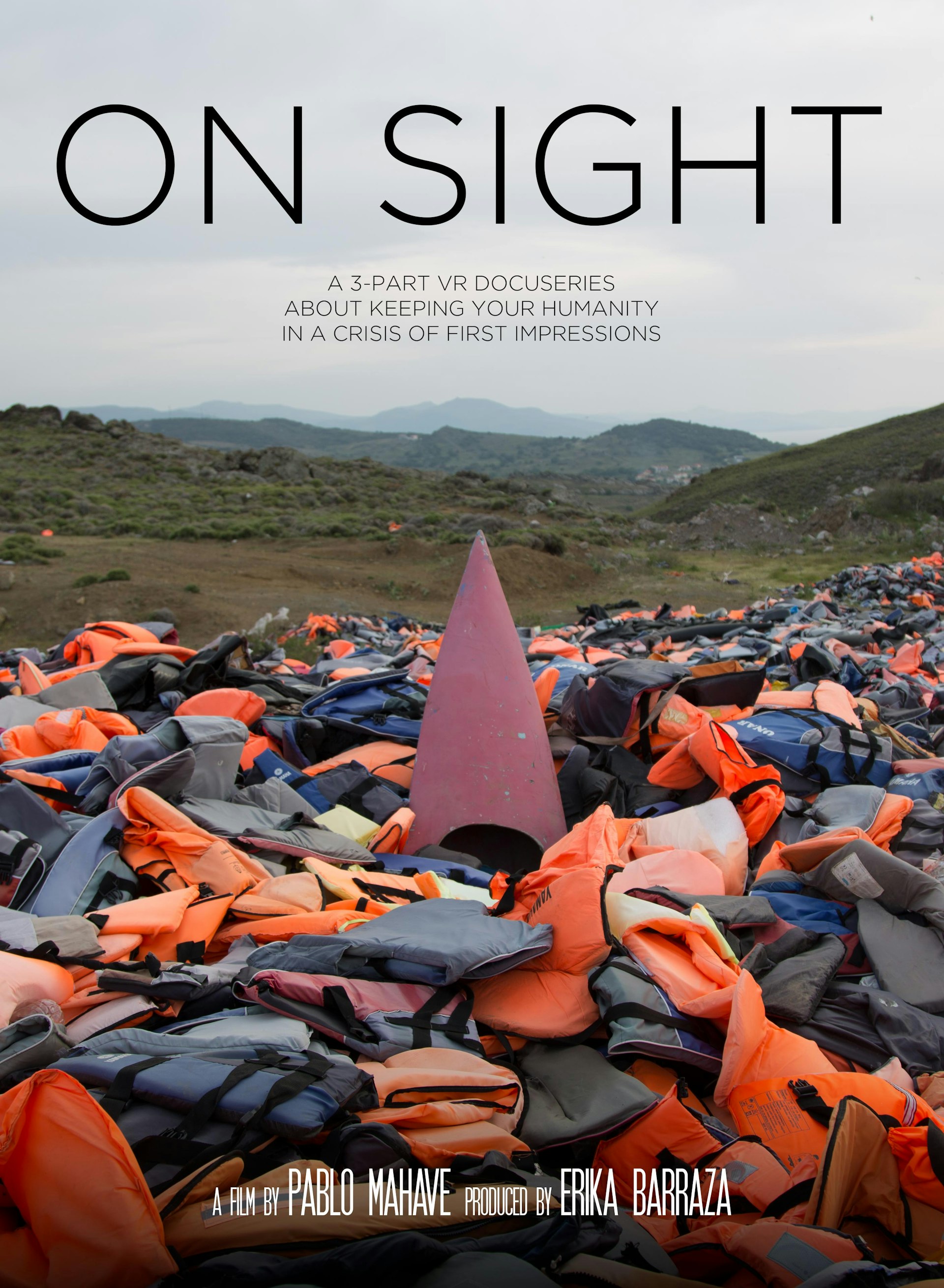

Despite how problematic much of the reporting on the refugee crisis has been, it’s hard to argue it’s an underreported issue. Yet the news cycle often moves on and boredom, or if you’re being generous, ‘compassion fatigue’, sets in long before the desperate situations improve for those forced from their homes by violence. By handing over control of the filmmaking process to three Afghan brothers struggling to rebuild their lives in Greece, Pablo Mahave’s On Sight shows how VR can be used not just to raise the profile of humanitarian issues, but empower those affected to share their perspectives.

“[With any traditional media] there is always a filter between reality and the delivered message,” Pablo explains. “If there is a medium that can cut out the middleman, then it’s VR. There was no script, no pre-planned story outline and the brothers made the key decisions themselves. This piece is an experiment that seeks to put the spotlight on the dignity, empowerment, respect and decency of the people portrayed.”

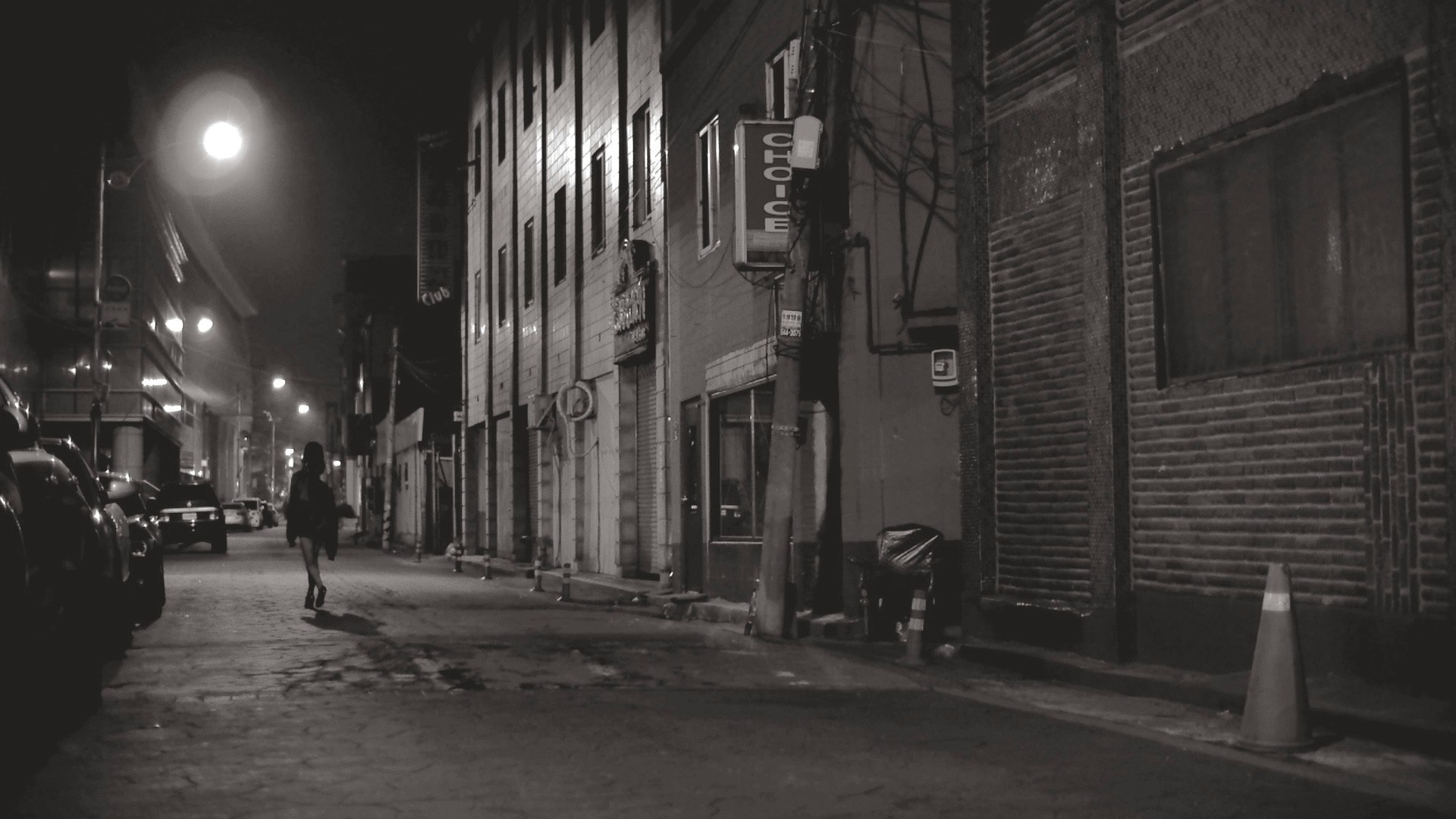

At 1AM on October 28th, 1992, the body of a 26-year-old South Korean sex worker was found at a decrepit house at the Dongducheon camp town – one of 96 such towns that have sprung up to service the (sexual) needs of US soldiers stationed in nearby military bases. Her body was covered in detergent powder to dispose of evidence but a brain haemorrhage was established as the cause of death. Two beer bottles and one cola bottle were found inside her uterus and an umbrella penetrated 11 inches into her rectum.

Although US soldiers stationed in South Korea commit an average of eight crimes per day, including murder, assault and rape, they escape punishment because their victims are usually sex workers, who operate in these special zones which fall under the jurisdiction of neither country. This particularly brutal attack caused a mass protest demanding the perpetrator be tried in the court system. But five-time feature film director Gina Kim couldn’t find a way to tell the story – until she discovered VR.

“The media covered the horrific image of the mutilated body of the victim and the image also showed up on the posters and flyers created by the people participating in the protest,” Gina says. “Every time I saw the picture, I saw the victim’s dignity being once again destroyed. For the last 25 years, I have struggled to find a way to make a film about this tragic incident. As a female director concerned with the female body, I have never been happy with how gender violence is represented in cinema: violence becomes a way of reproducing the violence itself and exploiting the image of the victim. But I realised the potential of VR to tell the same violent story, without showing or exploiting her image. Viewers cannot remain distanced, passive spectators, since they become part of the scene.”

Bloodless won the festival’s Best VR Film Award and hauntingly recreates the victim’s last moments, in the process reawakening the debate about continued abuses perpetrated by US soldiers in South Korea and the lack of justice. “I determined to have her ghost guide us through the dilapidated streets, the club that she met the soldier and finally the small room where she was mutilated and died,” Gina says.

You feel the claustrophobia of the empty room before you notice the blood oozing slowly onto the floor at your feet. You feel trapped, disgusted and want to run but you can’t, you’re stuck there as a witness to a death that went unnoticed – a death you can no longer ignore.

“I do believe VR is an empathy builder,” Gina says. “By far, the majority of tragedies in this world are caused by the profound sense of apathy and misunderstanding. But if used well, VR can promote a new way of communication that allows a totally different intensity of empathy; empathy without exploitation. You can ‘become’ someone else, which no other artistic media achieves. It allows you to understand and experience the pain of others.”

Bloodless, On Sight and We Who Remain played at the 58th Thessaloniki International Film Festival in Greece.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.