What happens after you get deported?

- Text by Bethan Staton

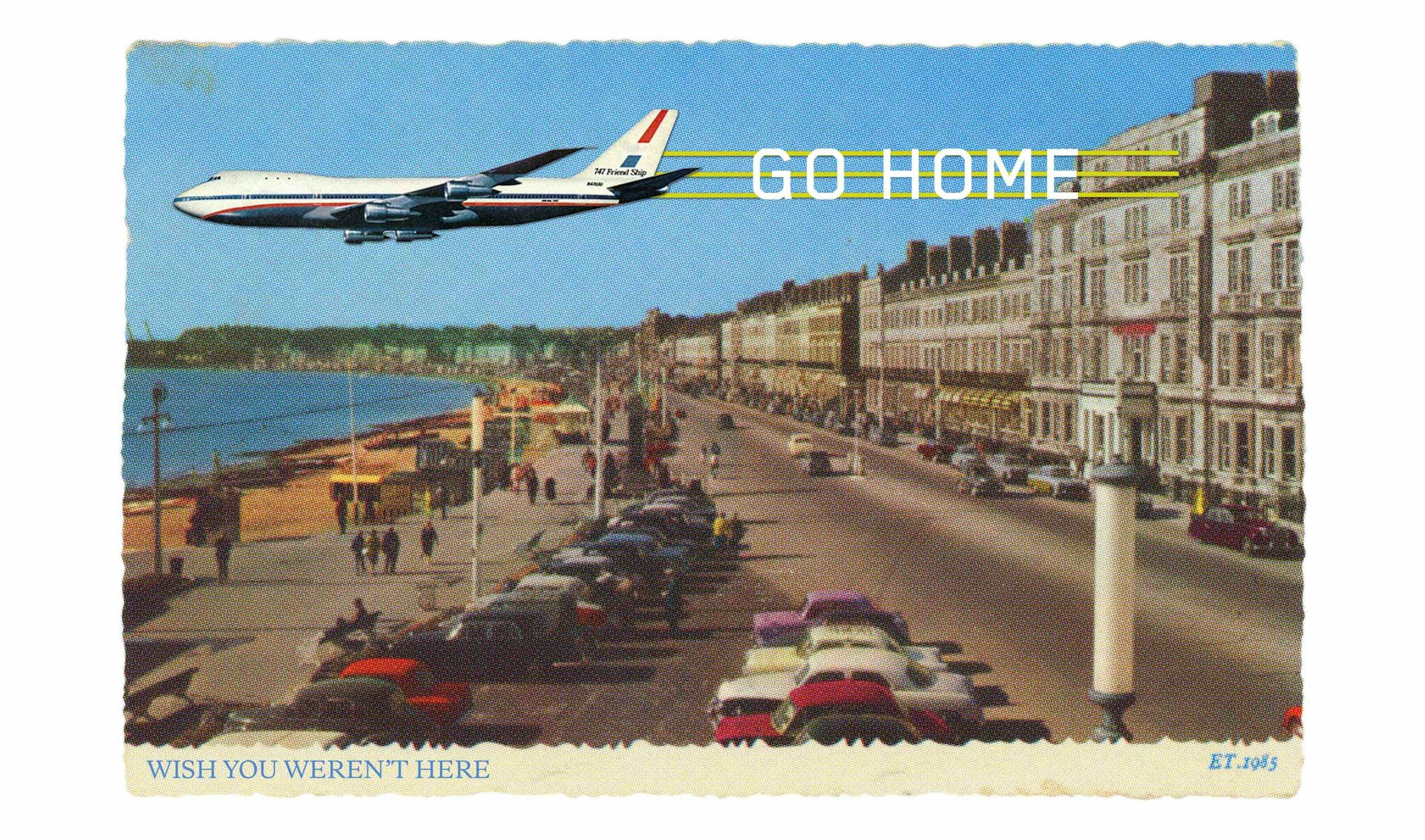

- Illustrations by Eve Izaak

Paul Robinson is hungry. After two months in Jamaica, he has no money, no job and no papers. This morning, he complained of burning in his chest: acid, his neighbour said, from an empty stomach.

“It’s a nightmare,” Paul says. “I was dropped here with nothing. Nothing at all.”

He is one of 29 people deported on the first chartered removal flight from the UK to Jamaica since the Windrush Scandal. He had lived for 19 years in Britain, where he has a partner and child. But after being convicted of a drugs offence he was branded a foreign national offender, his leave to remain in the country stripped.

Like many of those on board the flight, Paul knew virtually no one in Jamaica when he landed. He lacked the paperwork to even fix a money transfer, and had to stay with a distant friend. Tensions in his hometown mean he can’t go back for fear of violence. But even in Kingston, marked as an outsider and returnee, he fears for his life.

Now, he’s getting help from the National Organisation for Deported Migrants – a charity founded to help returnees. Oswald Dawkins, its president, is helping him secure a birth certificate and national ID – documents Paul doesn’t have and can do little without. But these cost $18,000 Jamaica dollars (£110) and months of processing, leaving Paul in limbo.

NODM’s resources, and future, are also uncertain. The Home Office says it works with NGOs to fund support for deportees, but NODM’s funding from the UK High Commission ran out in March. Oswald says it’s left the country’s only devoted deportee charity fearful for its future.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t know how long we’re going to be sitting in this office,” he says. “We could be in the position where, if Paul called me, we’d have to say ‘There’s nothing we can do.’”

NODM helps dozens of people who arrive in Jamaica with nothing, Oswald says. Most end up staying with what he calls a “semblance” of family – distant aunts or cousins who are the only connection to Jamaica after years overseas – in the painful balance of precarity and dependence that sofa-surfing often brings.

It’s the situation Chevon Brown now faces. He left Jamaica at 14, and had expected to spend his life in the UK where he has a partner and was training to join his father’s barbering business. He was deported after a driving conviction for which he spent eight months in jail.

When his phone was cut off on the night of the deportation – the Home Office never confirmed his departure – Chevon’s father Vance called friends to pick him up from the airport. The 22-year-old is still staying with them, with Vance sending money for board.

“They’re nice people but I feel like I’m weighing them down,” Chevon says. For several weeks after arriving he stayed inside, depressed, fearful of being attacked, and unsure of what to say to his hosts. He’s since got to know the family better, but still rarely ventures out.

Finding a job seems an impossible task. Government statistics place unemployment at around 9 per cent in Jamaica and as an outsider with a criminal conviction, Chevon is at a disadvantage. When the charter flight left, Sajid Javid said all those on board had been convicted of serious and violent crimes and needed to be deported for public safety; Chevon fears the label has stuck.

“I got labelled as a rapist, a murderer and a trafficker,” he said. When he walks around, he’s anxious that everyone is recoiling from him. “I don’t know what everyone’s thoughts are. But you can still see that look on their faces – they know what they’ve labelled us as.”

Back in Oxford, Chevon’s father is doing his best to reassure his son. When they talk on the phone, he tries to avoid talking about his efforts to appeal the deportation, or how he is coping without him.

“My family is all over the place,” Vance says. He believes Chevon has been “chewed up and spat out by the system” and is worried for his younger brothers, who are becoming more distant, angry and hurt about Chevon’s removal.

“My 17-year-old son is struggling the most. He’s been very quiet,” Vance says. “He thinks might not ever see Chevon again – and they were tight, good friends.”

Unlike Paul, Chevon has not contacted NODM and neither he nor Vance received any communication from the Home Office after the charter flight. Oswald says their situation – the stasis, difficulty finding a job, sofa-surfing – is usual. It also means deportees are at higher risk of destitution and turning to crime.

“People who’ve been through it say it’s ‘one of them things’,” Oswald Dawkins says. “It’s not ‘one of them things’. How can be when a person is in the UK since he was five, has a job, a partner, a skill set, a house, then is taken away?”

For Chevon, the way forward doesn’t look clear. He says he feels like he should be “moving forward, getting on with my life” but cannot see how. He spends much of his time playing his arrest over in his head.

“I always think about it. How I should have pulled over,” he says over the phone. He blames himself, but cannot understand how deportation – imposing a “double punishment” after his sentence was served – could be justified.

“I’d say it was a life-changing experience, being taken onto that plane,” he says. “I thought I had the right to stay in the UK.”

Learn more about how you can help stop deportations by visiting the End Deportations campaign page.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.