Why Christmas is the loneliest part of my year

- Text by Amrou Al-Kadhi

- Illustrations by Simon Hayes

For Christmas this year, I wrote to Santa to bring me a loving boyfriend, accepting parents, and as a second-generation gay Iraqi-drag queen, the feeling that I properly belong here in the UK. The white bearded patriarch descends on his mighty sleigh in just a few days, and yet, no such luck. Bastard. He’s probably busy with a white middle-class family in Fulham, bestowing Harrods toys to Rupert and Cassandra.

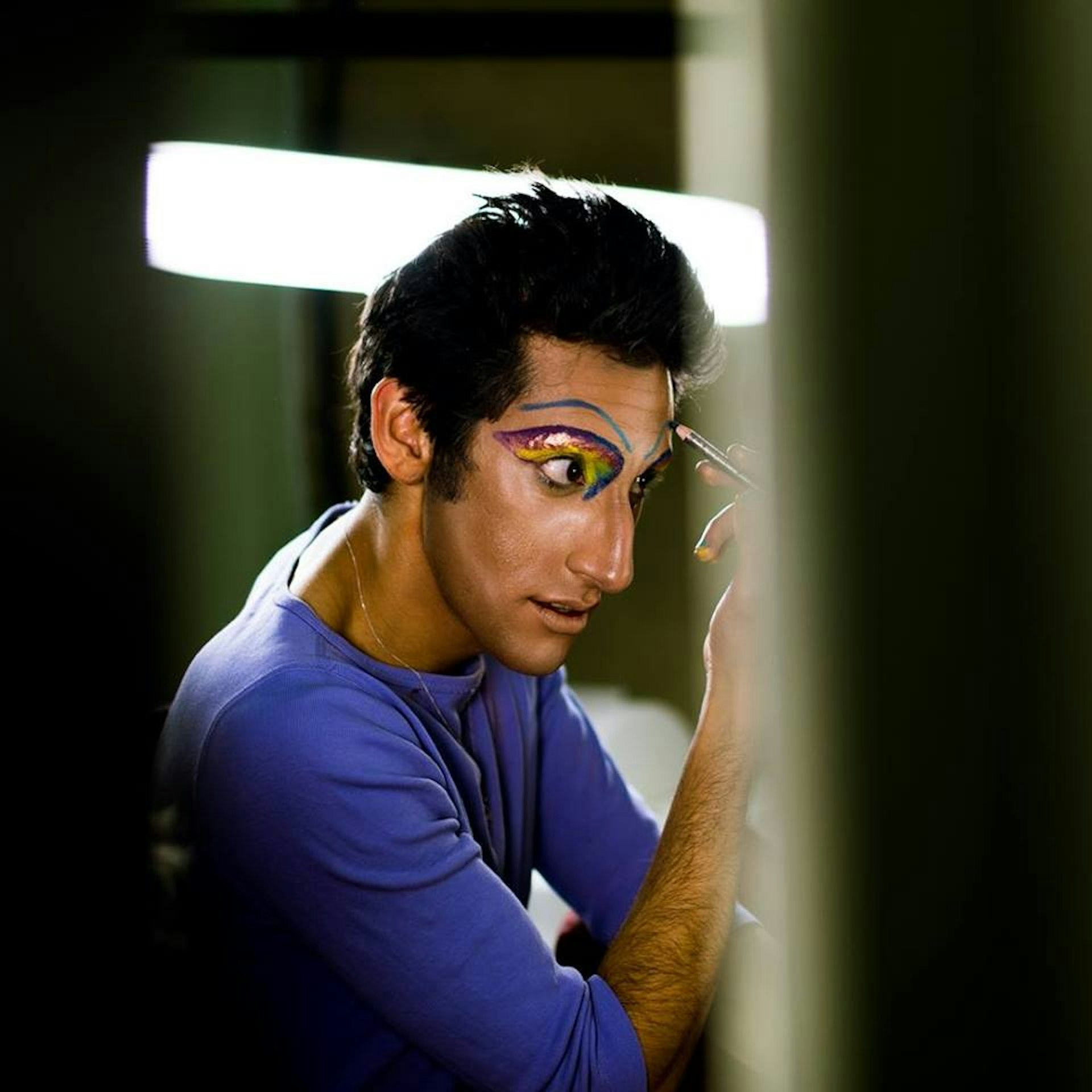

So to fend off isolation this December, I gifted myself with a queer unicorn warrior tattooed across my chest. As most of my friends escape their urban chaos for some “real, quality time with family,” I have a fetish unicorn in a leather harness keeping me company, straddling my nipple, ready to tear shit up. My need to get this inked before Christmas day bordered on obsessive, but the wonderful Jose Vigers (queer tattoo artist extraordinaire), empathetic to my desires, made time for me. A wounded queer unicorn about to attack might not seem the immediate festive piece, but I wanted desperately to mark what Christmas means to me – a season of queer survival.

Though I’m very lucky to have friends in London who take me in during the holidays, it doesn’t shed the feeling of displacement Christmas has engrained within me. For almost three months, our city is saturated with images of cohesive family units, coming together to celebrate “the important things in life” – though things not implicitly available to queer immigrants living in the UK.

This year’s spread of Christmas adverts again shows why. For instance, Sainsbury’s holiday animation repeats the saccharine jingle, “I want to find the greatest gift I can give my family – the greatest gift I can give, is ME!” A touching (if not delusional) sentiment, but if you’ve suffered familial rejection, the idea that “being yourself” is the best gift your parents could wish for hits a sour spot. Me in Christmas drag wearing gold tinsel for a headband would hardly be mommy and daddy’s ideal prezzie; me in a shirt with a wife by my side – their prayers to Santa (Allah, really), finally answered!

Amrou

Morrisons and Lidl’s campaigns were similarly predictable and depressing. If I see another entirely white family passing gravy round a dinner table, chuckling about shared, good times, I’ll throw the ready meal I usually eat home alone on Christmas at the fucking TV. And infuriating for different reasons, Burberry’s ‘Festive Film’ is purely offensive. In an apparent celebration of all things ‘British,’ it rejoices in Thomas Burberry’s colonial excursions, and how he brought back tools for invention to a once imperial England (and according to the advert, its exclusively white citizenship). Finally, a brand that delivers on the promise of Brexit and Britain taking back control!

This year, I reached out to other LGBTQIA+ immigrants who might share my feelings about Christmas. And in my search I came across the wonderful project Rainbow Pilgrims, led by Surat-Shaan Knan and supported by Lottery Heritage Fund and charity Liberal Judaism. I spoke to Surat-Shaan about what they are trying to create. Aiming to empower isolated LGBTQIA+ migrant communities and groups in the UK, Rainbow Pilgrims brings together displaced identities to collectively share experiences. They aspire to do this through oral history and storytelling, by collecting and archiving suppressed histories, and in pop-up events that bring together queer people of faith and colour, helping foster a sense of belonging.

When I raise the topic of Christmas to Surat-Shaan, we compare our feelings of disdain for the season of ‘joy’. They explain that for LGBTQIA+ immigrants living here, the sense of marginalisation is two-fold – many are rejected from their cultural community due to their sexuality, and many don’t feel welcome in an increasingly xenophobic Britain. I understand this feeling of hovering between two fractured worlds; “too Western” for my Iraqi community, and “too Iraqi” for a Christmas Britain.

Surat-Shaan talks to me about how the pretence of collectivity at Christmas is no more than a smokescreen for selfish behaviours. With the belief in God replaced by a devotion to Western capitalism, Christmas is the month of pure consumption. Your resources are directed entirely at family-pleasing purchases, and those of us on the outside aren’t offered a slice of the mince pie. My self-worth can quite literally plummet through being sidelined in the chaos of Christmas consumerism. As a way to combat this, Surat-Shaan and their team believe in the potential of ritualistic objects, where power lies in their meaning, not value.

As part of their work, they host events where LGBTQIA+ immigrants each share an item or food dish of cultural significance, using objects to bring people together and communicate, rather than leaving many pressing their noses enviously against the high-street glass. Such happenings want to reignite the “powerful and ritualistic collectivity that Christmas should be – and was initially – about,” Surat-Shaan tells me.

And so this Christmas – and every Christmas from now – I have a queer unicorn warrior as my totem, its permanent ink a constant companion, a gift to fight off loneliness, there to tell my story to anyone who asks.

Amrou Al-Kadhi is a writer, performer, filmmaker and creative director of drag troupe Denim.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.