David Lammy: ‘You can’t buy your way out of Covid-19’

- Text by Ben Smoke

- Illustrations by Emma Balebela

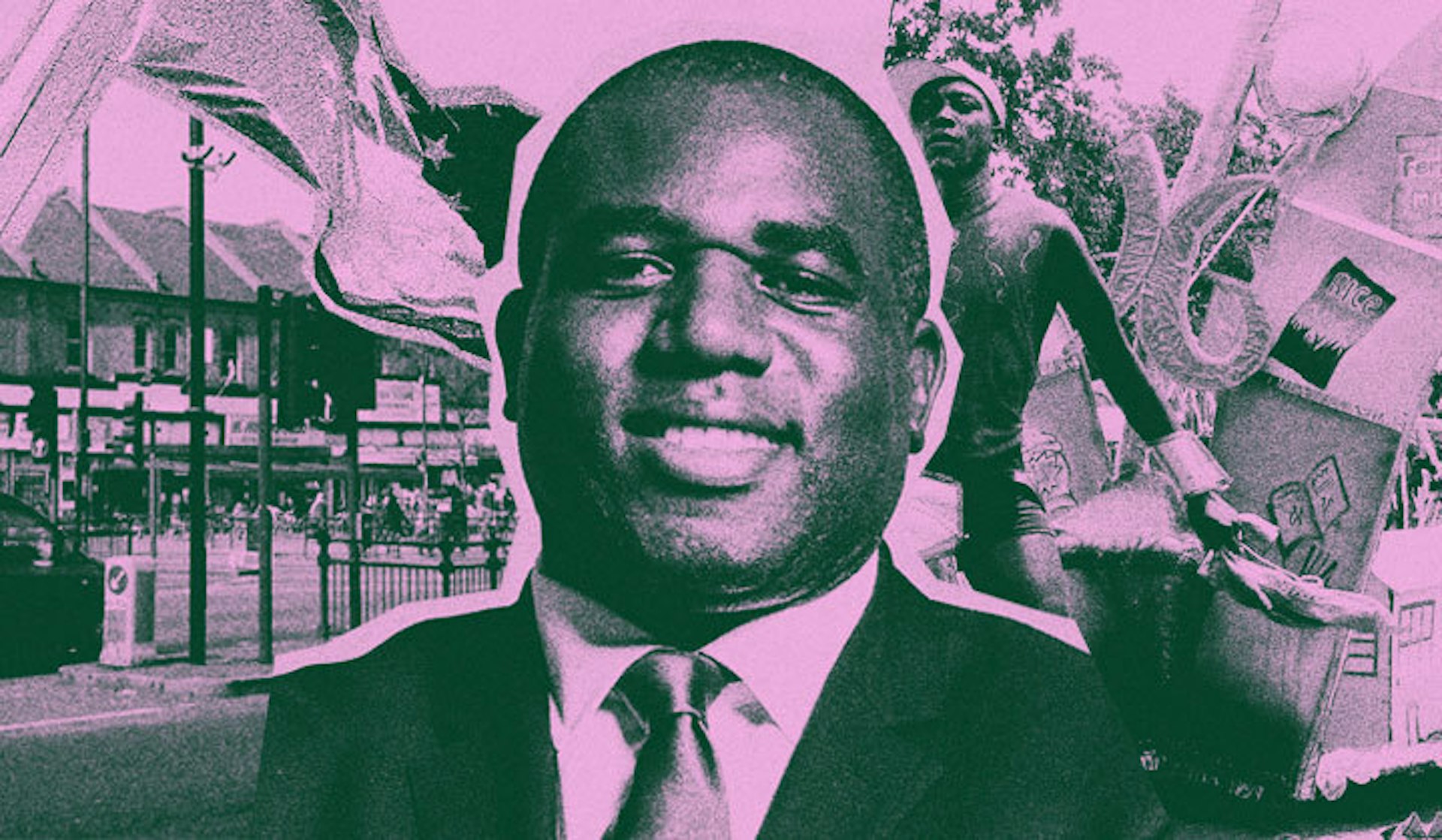

In the last few years, David Lammy has been a powerful voice on the backbench. Whether it’s reviewing the treatment of BAME people in the criminal justice system, or speaking out loudly for those affected by the Grenfell tragedy and the Windrush scandal, Tottenham’s Labour MP has made a name for himself as a powerful and passionate orator.

Having served as a minister in both the Blair and Brown governments, Lammy left the frontbenches in 2010 after Labour’s general election defeat. He caused controversy in 2011 when he called for the relaxation of smacking laws in the wake of riots which erupted in his home constituency, which he’s represented since a by-election in 2000. A year later, the MP – whose father left him and his family when he was 12 – caused a further furore when he claimed that absent fathers were a “key cause of knife crime”.

Lammy has also been one of the loudest proponents for remain in the wake of Britain’s decision to leave the EU. Alongside newly minted Labour Leader Keir Starmer, he fought for a ‘people’s vote’, gaining notoriety, acclaim and disdain in the process of doing so.

As he campaigned to remain, receiving daily death threats and abuse, Lammy sat down to write Tribes. Part memoir, part call to arms, Tribes looks at the very human need to belong, and how that can manifest in positive or deeply destructive ways. The MP – who was educated at a boarding school in Peterborough, born to Guyanese parents and raised in Tottenham – set about figuring out why we group together, and how we can start to harness that desire for the good of society.

As the country went into lockdown, we jumped on the phone with the newly announced Shadow Justice Secretary to talk about the book, the rising threat of the far-right, and how Coronavirus is exposing both the best and the worst of our society.

Tribes explores some of the groupings that, for better or worse, we naturally form as human beings. Do you think the current pandemic is exposing some of the weaknesses inherent within some of those ‘tribes’?

Child psychologists do a test with primary school children where they give them different coloured t-shirts and not explain why. Over time, despite having no reason to, they start to organise themselves according to the colour of the t-shirt. So there are innate tribal instincts that are in all of us. The problem is, in an individualised liberal democracy, people can be seduced by very toxic tribes and move to very alienating, exclusive kinds of behaviours.

And actually, because of the coronavirus, we’re seeing a need to look out for your neighbour, a need to be concerned about those who are on the frontline like our nurses and our doctors, and we’re hearing all sorts fantastic stories of generosity and support. On another level, we’re also seeing great selfishness; hoarding of goods, not looking out for nurses and doctors who also need to feed their children and provide for their families. We’re also seeing total abandonment of government messages; people who are still happy to flout rules about social distancing.

“If you lay down with dogs you get fleas, and that is what has happened with the far right rhetoric in this country.”

Labour MP David Lammy says the “inhumane and cruel” treatment of the Caribbean Windrush generation is a “national shame”. pic.twitter.com/NRa4umqaqJ

— Channel 4 News (@Channel4News) April 16, 2018

You talk a lot about moving past those tribes, but do you think our ability to do that is curtailed by the neoliberal reality we’re living in?

I’m concerned about a populist, nationalist movement that’s gripping much of the world. We have to understand the nature of social media, which is very divisive, and there’s definitely politicians manipulating that for their own ends at the moment. Most of them – Trump, Jonathan Bannon, Farage, Bolsonaro – are connected and very well-financed, and that is deeply, deeply worrying.

They, and often we, tend to look backwards to history, and it’s a mythologised history. We say things like, ‘we won the second world war in our darkest hour’ when in fact, Britain did not win the Second World War on its own. It won it with the Commonwealth and with the help of America. It won it because Russia was on our side.

How much of that mythologised nostalgia do you think is influencing the national conversation and the UK Government’s reaction to the coronavirus?

We live in a liberal democracy. It’s a democracy that encourages free will and freedoms. But we are in an age where people are very conscious of their rights, but perhaps less conscious of their responsibilities. The sorts of views you’re hearing – from Peter Hitchens, Dominic Cummings, those sorts of individuals – are libertarian views. They are scathing of the role of the state and the role of government. They are equivocal about the vulnerable, the elderly, and minorities.

In this country, after the Second World War, we built the welfare state that we have today. We built the NHS, which we are going to rely on so heavily over the coming months. I think that we have to ignore those libertarian voices, as they’re normally from individuals who’ve got sufficient money to provide and help themselves. Although this is a crisis that demonstrates that even money can’t buy your way out of Covid-19. It reminds us about our common humanity, and our common purpose and desire to survive. It also reminds us particularly to support those who are vulnerable in the face of this terrible illness.

A lot of the book is about exploring the tribes that you are part of within the nation: what did you find most interesting about that?

I was writing this against the backdrop of Brexit and a really intense political period. I got a lot of abuse from racists and xenophobes, and was sent death threats. I think that, in a way, it was therapy. Exploring the tribes from which I belong, going to Niger and tracing my DNA back to a country I had barely heard of. Going back to Peterborough, a city that means a lot to me. Also, listening intently in little England to those who took a different view to me on the Brexit issue, and voted leave. The age we’re in is manifest with a profound sense of a lack of identity or lack of belonging.

How important is it, do you think, to hold onto those identities?

I’m at an age now where I’m pretty secure with who I am. There’s no question of losing sight of the bits that make me English. I’m very proud of my Caribbean background. I’m very fond of the city of Peterborough and the community I grew up in Tottenham, that has made me who I am. And I will always stand up for those who are minorities. That is because of my heritage, and my understanding of many relatives and friends, who’re living in a poor country, like Guyana and South America. So who I am at this stage of my life is very clear.

I’ve always been very clear that I in the House of Commons have this tremendous platform – it’s a platform that many of my constituents couldn’t dream of having. And they expect me to speak up on their behalf. Sometimes, people suggest I’m quite robust in my political views but the truth is nothing I say in Parliament is as robust as my constituents say in the barbershops, the post office queues, and the supermarkets of Tottenham. Mine is always a much more sanitised version! I’m really clear that that’s my job and I take that very seriously and in a way the exploration of my own background and identity has assisted in that purpose of knowing exactly where I stand in the ground and the issues that I stand for.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Tribes is out now.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.