How food banks are weathering the cost of living crisis

- Text by Ben Smoke

- Photography by Aiyush Pachnanda

Joe Walker is walking between the buildings at the food bank and community cafe he manages in Whitehawk, east Brighton.

Nestled between “a big hill and a racecourse”, the area is in the most 1,000 deprived wards in the country. Just a mile down the road from affluent Kemptown, Whitehawk could not feel further apart.

“It certainly has a rep, but when you get here you realise it’s not deserved – it’s a community full of friendly people trying to get on,” Walker, who grew up in a similar area on the other side of the city, says. “It’s a big council estate with 70 per cent social housing. It has some of the highest indicators of deprivation in the city and many of those we see at the food bank face the socio-economic challenges associated with them.”

There has been a food bank in this area since 2015. Operated by the Trussell Trust, it is one of more than 1,200 food bank centres in the charity’s network, which make up around two thirds of all food banks in the country. From 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021, the trust distributed 2,173,158 food parcels, of which 832,109 were for children.

It’s been four years since Joe first started working with Whitehawk food bank, first as a volunteer before becoming the manager. In that time, demand has skyrocketed. In the financial year 2018/19, the food bank distributed just over 1,000 parcels. The next year the number shot up by 52 per cent to over 2500. In 2020/21, as the pandemic raged, the number of parcels increased by an eye watering 209 per cent to over 7,000. It’s continuing to grow. Last year, Whitehawk, which serves an area with a population of around 14,000 people, distributed 8,309 parcels.

The food bank operates across two spaces. The first, a church on the main road running through the area aptly named Whitehawk Way, is open to all as a community cafe. People can come here and drink free tea and coffee. Pastries and cakes are partly bought by the trust and partly donated by Sussex Bake Down – a community interest company which sees hundreds of people in the area baking cakes at home and dropping them off at hubs to be distributed to food banks and projects in the area.

There are also opportunities for residents to come in and get advice on housing or money issues. Once a month, caseworkers from local Labour MP Lloyd Russell Moyle attend the cafe, which opens once a week on a Thursday, to offer assistance to members of the community.

In the more private basement of the church, volunteer befrienders sit down and talk to food bank users, taking their orders, talking through services or referrals they may need and asking them about their week.

“The reasons that people have to come and access our food bank are multifaceted,” Joe explains. “It could be a benefits problem that is often associated with years of struggling with a health condition. Or mental health issues which have built up because of debt issues. Or any number of things. So our support has to be much more holistic and wraparound compared to other food banks that maybe act as an emergency port of call because someone’s waiting for Universal Credit. But after that they can be self-sufficient from what they receive.”

Prior to the pandemic, the food bank operated out of the church, in the space now given over to the community cafe. Next to the church is an old community centre, which shut down around eight years ago. “When the pandemic happened, and we could no longer meet in person, we got in touch with the trustees of the centre and asked if we could use the space for the food bank – to store, sort and distribute parcels from,” says Joe. “They said yes, and we’ve been there ever since.”

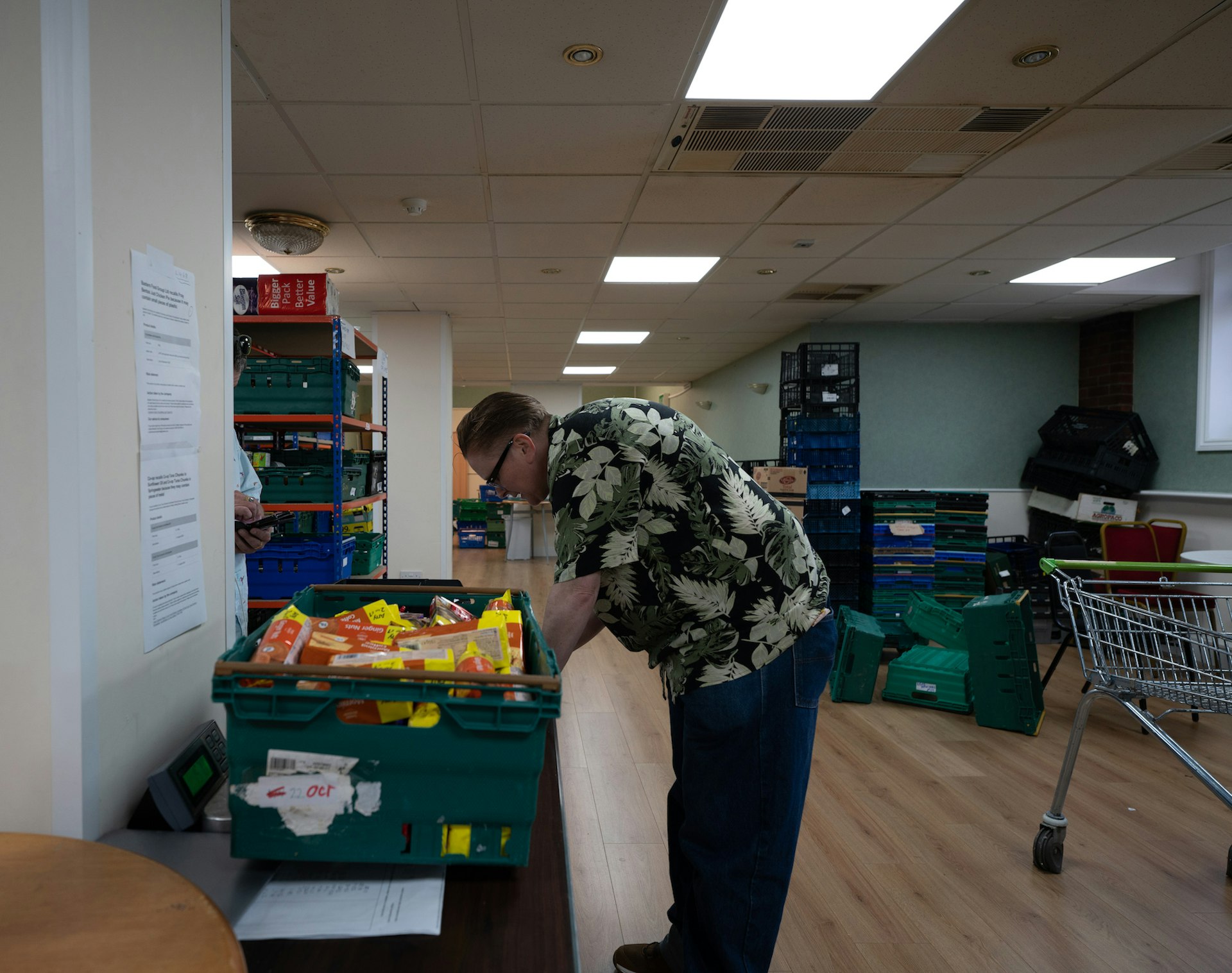

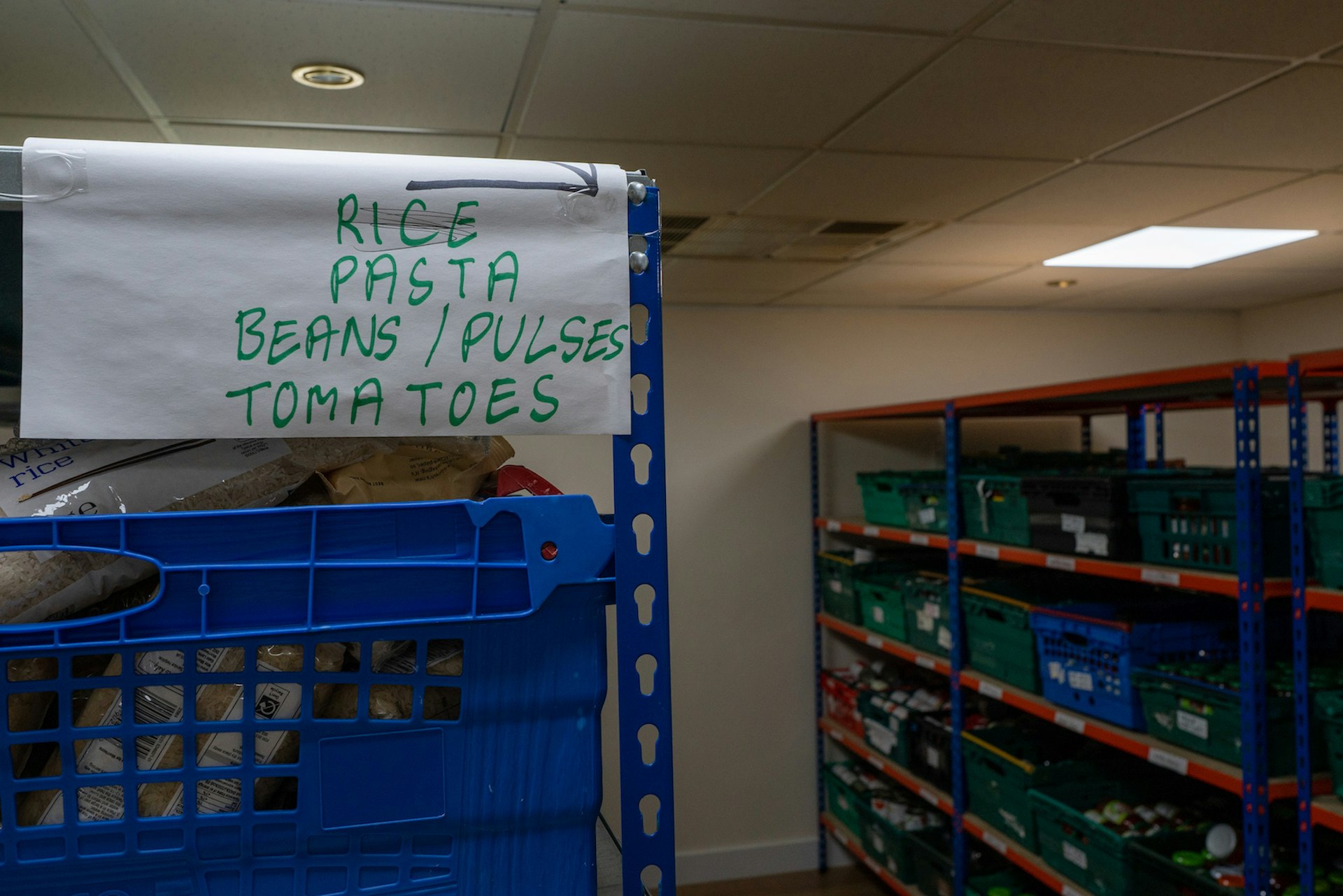

Inside the centre, a big cavernous space is given over to rows of shelving units packed full of food, toiletries and goods. Volunteers and staff sort through donations, many of which are received from the surplus of local wholesalers. They weigh trays of soup and pasta to keep track of stock levels before moving them through to the sorting room.

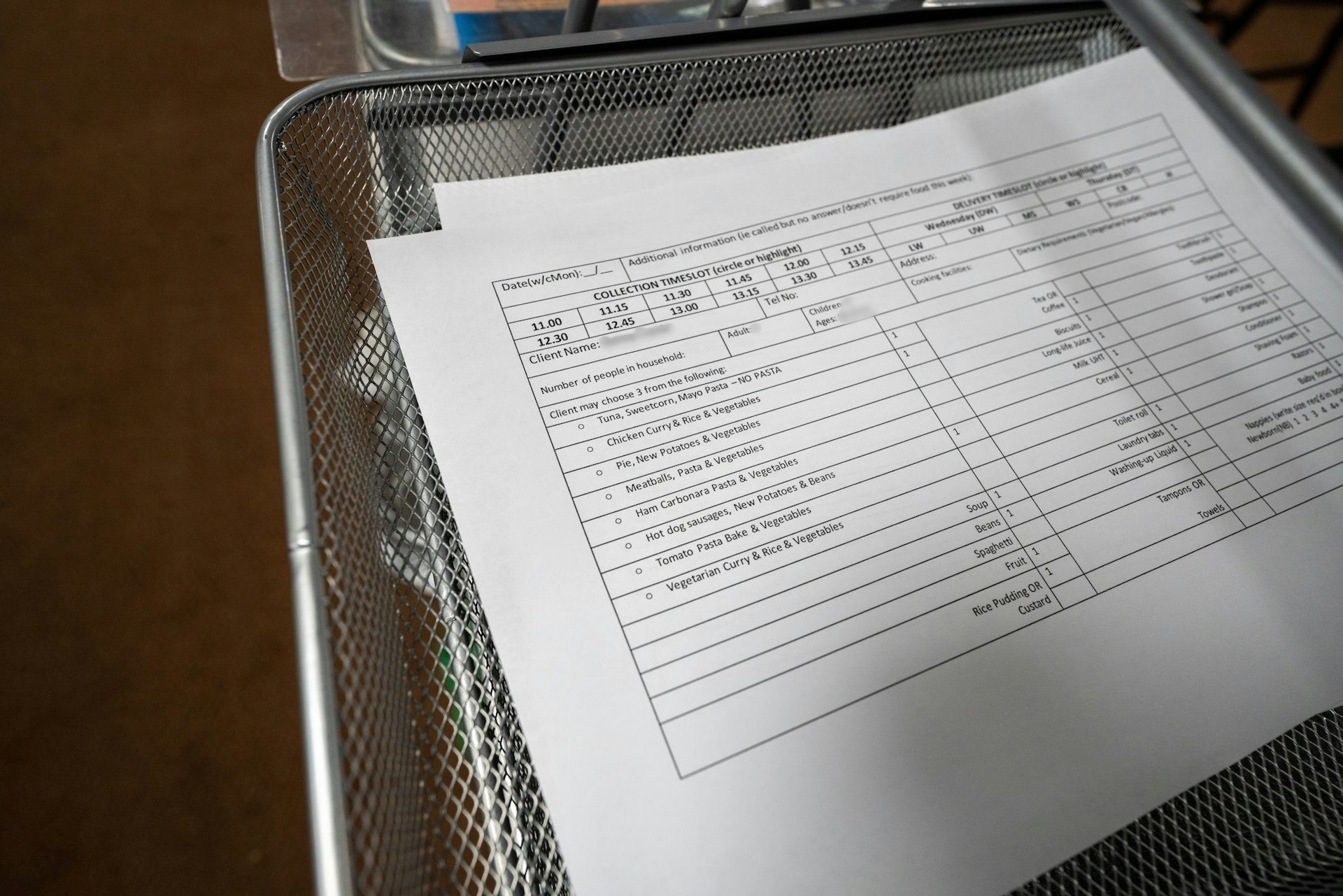

“When a client is with a befriender, they go through different meal orders for the week – we offer a wide selection, including those which take less energy to cook – so maybe someone will request microwave rice over a packet,” Joe tells me as we walk through the sorting area. These options have been particularly useful for those in halfway houses or temporary homeless shelters in the area, though, as the energy crisis builds, the requests are increasing.

“It’s become a much sharper issue over the last couple of months. Lots of people have been telling us my bills have gone from £70 to over £140 a month. If you’re already really struggling to get by and you’re already having to make decisions between cooking yourself some pasta and heating your home over the winter, when the increase comes in, it’s not even a decision anymore, you can’t do anything. We’re seeing more and more of those testimonies from people needing to have food that they can cook in a microwave instead of using the hob because it costs less on their energy bills and things like that.”

The worry, staff at the food bank explain, is that come September and October, with yet more planned energy increases, the demand for help and assistance from the food bank will explode. They’re already planning campaigns for the local area to encourage people to come in and seek assistance now to avoid debt, arrears and stress building up. In many ways, it feels like the sharp inhalation of breath before hitting the icy waters of crisis.

Each client has a specific form which shows their preferences, and the room is layed out to follow the order of the form, with volunteers filling bags ready for users to collect. There are boxes of toiletries and hygiene products as well as treats and crisps. “We try to keep those stocked up for the kids at half terms and on school holidays.”

In many ways, it is a uniquely depressing experience. A tray of order forms sits on the side, each representing a person or family in urgent need of assistance. Each a damning indictment on 12 long years of Conservative government. Despite the sadness, the struggle and deprivation, there is hope here.

Around the corner in the community cafe, residents sit and chat with one another. Children run around the tables, high on sugary drinks, their cackles echoing over the din. Volunteers and local residents enquire after one anothers families or lives. There is a connection here; a togetherness in the fight. It’s in that connection that hope lies.

Outside the food bank as they wait for their orders, clients and volunteers sit and joke with one another in the sun. They are genuinely happy to see one another. Around the corner, sat on the steps of the church, Joe explains his complicated feelings about the food bank and his job more broadly.

“In one way you’re proud of what you’ve achieved in terms of there’s a need and you’ve been able to support people. But at the same time, you’re constantly aware that you don’t want to be doing this,” says Joes. “I’d much rather people be able to have the income to be able to choose what they spend it on. To have their own choice not have to kind of come to us for a charitable handout.”

“We’re so proud of what we’re able to do but charity is not the way we want to operate going forward. In an ideal world we (the food bank) would not exist”.

Ben Smoke is Huck’s Politics & Activism Editor. Follow him on Twitter.

Follow Aiyush Pachnanda on Instagram.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.