How landlords are exploiting London’s homelessness crisis

- Text by Alex Norris

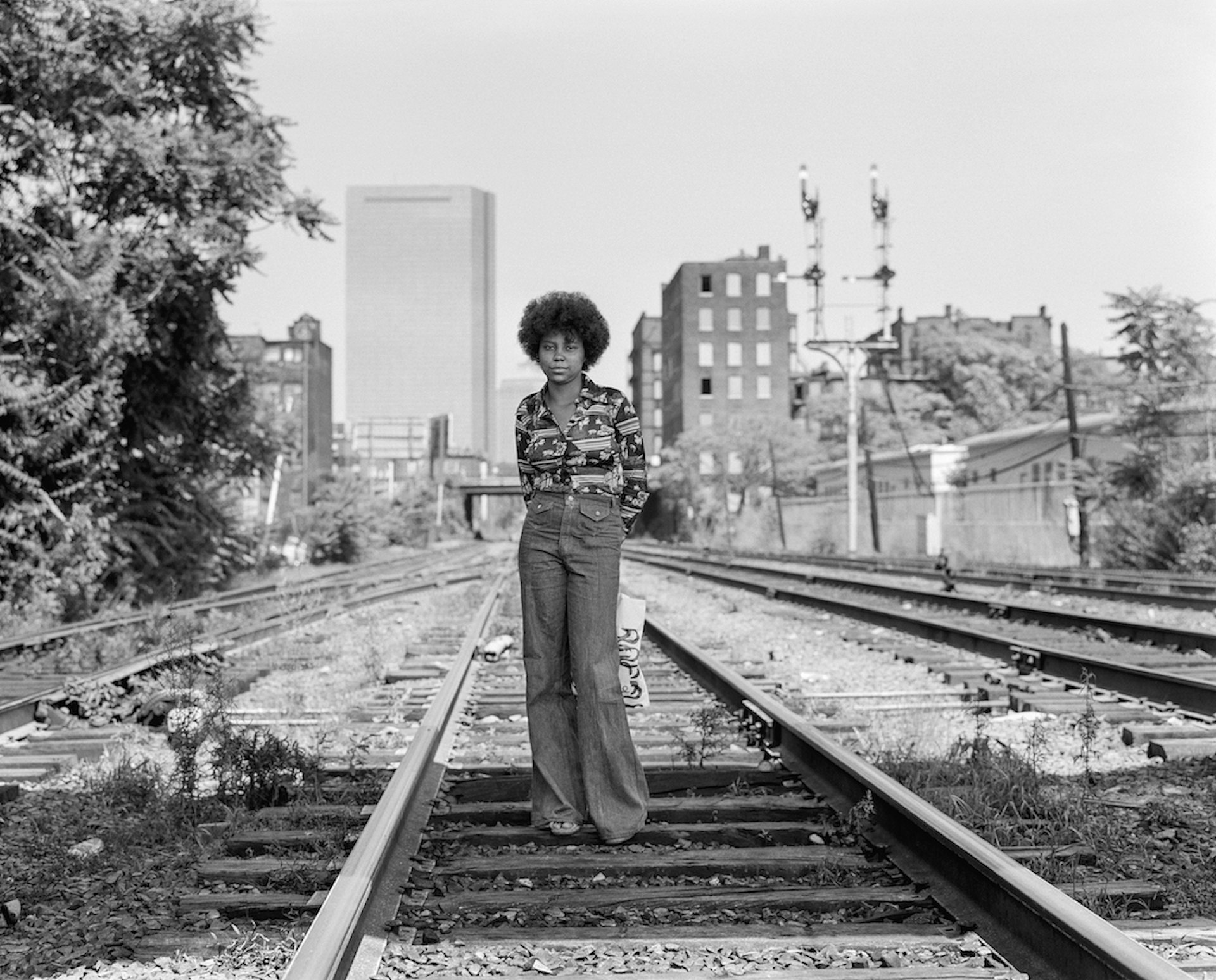

- Photography by Finbarr Fallon

The UK is in the grips of a housing crisis. Due to ever-increasing rents, a boom in the buy-to-let market and a scarcity of social housing, for many people, keeping a roof over their heads is an ever-present worry. In London – famed for its extortionate rents and huge wealth inequality – the situation is especially dire. With homelessness on the rise and the Covid-19 pandemic forcing droves more people into hardship, thousands across England’s capital find themselves in crisis. And as with any crisis, there are people willing to exploit it.

In recent years, letting agencies have found a way to profit from both London’s housing shortage and the vulnerable people it affects. The way they do this is simple. By letting out rooms exclusively to people on Universal Credit, then setting the rent at the maximum amount their benefits will pay, landlords funnel huge sums from the taxpayer-funded benefit system into their pockets.

It gets worse. In some London boroughs, Universal Credit will fork out rent costs in excess of £295 per week. This puts many people who are trying to get back into work in an impossible position. Once they start earning, their benefits will decrease or stop completely, leaving them with an eye-watering rent payment they simply can’t afford. This means many people are left entirely dependent on benefits, unable to work for fear of losing their accommodation and unable to live elsewhere unless they can manage the hopeless feat of saving up a deposit.

Often, these agencies target people trying to escape homelessness, knowing they have little option but to accept whatever is on offer. Glass Door Homeless Charity coordinates the UK’s largest network of open-access services for people affected by homelessness. “Many people who are looking to leave homelessness behind have no other choice but to turn to the private rented sector,” says Neil Parkinson, the co-head of Casework at Glass Door. “These agencies charge the maximum they know benefits will pay, for what in some cases can be houses cut up into a collection of very small studios. Some of these can be in good condition, but others are frequently badly maintained. In London, these properties are located almost exclusively in the outer areas of the city. Tenants who take these properties too often then find themselves displaced to unfamiliar areas and become socially isolated.”

Between 2019 and 2021, I worked in the homeless sector supporting people who were sleeping rough. It was common for homeless people to end up in accommodation that was not only absurdly expensive, but often cramped and poorly-managed.

I’m reminded of Szymon*, a man who had just been discharged from hospital and was walking with the aid of crutches. Upon approaching his local authority for support, Szymon was told he didn’t meet the threshold for temporary accommodation, despite his eligibility for housing support and his obvious physical impairment. Szymon subsequently spent time sleeping in night shelters and, later, on the streets. When an opportunity with a letting agency arose, he was glad to accept it. But this came at a hefty price. With his rent costing over £1000 per month for a small en-suite room in zone 3, Szymon knew he wouldn’t find work to cover his housing costs. This left him dependent on his measly ‘standard allowance’ from Universal Credit and, to make matters worse, his payment was subsequently reduced to top up the cost of his rent. This is the impact of the benefit cap: money that Szymon could have spent on food or bills was effectively siphoned off by his landlord.

Disabled people are at particular risk of exploitation. When Szymon first met the letting agent who eventually housed him, they noticed his crutches and asked whether he was receiving Personal Independence Payment (PIP). This is a separate benefit from Universal Credit, available to people with disabilities. If Szymon had been receiving it, the agency would have increased his rent further, leeching off money that’s intended to enable disabled people to live independently. This is common practice among many agencies, and another symptom of an unregulated private sector that sees vulnerable people as cash cows they can exploit.

Rather than discourage people from taking up these tenancies, local authorities actively encourage them, offering ‘incentive payments’ to agencies who rent to their clients. Collaboration between councils and landlords has become inevitable in an age when public housing stock has been decimated and councils have to rely on the private sector to fill the gap. This often leads to clients with support needs, such as Szymon, being palmed off into poor-quality private housing in order to alleviate local authority caseloads. Even homeless charities are faced with little option but to work with agencies that will keep people dependent on benefits because so few other options exist.

In a tragic turn of events, Szymon died in 2020 during the first wave of the Covid pandemic. Having been notified of his death by his caseworker, I called the housing agency to find out what had happened. The agent was eerily upbeat on the phone, and almost immediately asked whether I had another client who could take his place. This mindset is typical of these vampiric agencies – when one client leaves, there will always be another one desperate to move in.

Polly Neate, Chief Executive of Shelter, knows the negative impact of these agencies all too well. “Sadly, this is another example of landlords and letting agents capitalising on our worsening housing emergency, and the fact people on low incomes often have no choice but to accept overpriced and substandard private rentals because there is nothing else,” she says.

This won’t end while local authorities allow it to happen. Last year, I worked with David*, a young man who was in his early 20s with a college education and ambitions of getting into the construction industry. David’s local council had sourced him accommodation with an agency charging almost £1000 per month for an en-suite room. While most people under the age of 35 wouldn’t be entitled to £1000 to pay their rent, David was a rare case who qualified for the upper rate of Universal Credit, as he’d spent so long living in homeless hostels. Because of the rife discrimination from private landlords towards people on benefits, he hadn’t been able to find accommodation himself. So, when the council offered him somewhere to live, like Szymon, he accepted it, even though his job prospects were suddenly scuppered.

For many people fighting their way out of homelessness, jobs in the construction, hospitality and retail industries are attractive because entry-level roles are widely available and often don’t require previous experience. However, starting salaries are generally insufficient to cover high rent costs, especially when bills, travel and essential living expenses are factored in. For David, this meant he was left languishing in poor value accommodation that prohibited him from starting a career. Additionally, he was put in the difficult position of having Universal Credit pressuring him to find work, while knowing that any job he was likely to get would leave him at risk of becoming homeless again.

Homeless charities are clear about what needs to change. Matt Downie, Chief Executive of Crisis, says: “To prevent more people facing homelessness being forced into inadequate housing, we urgently need the UK government to seriously commit to building more affordable homes. 90,000 new social homes a year are needed in England to address the backlog of need.” Neate is of the same view: “The only way to level the playing field and make sure more people have access to homes that are safe, suitable and secure is for the government to invest in a new generation of social housing. Until then, local councils must use their powers to crack down on substandard rentals, and those willing to exploit people for profit.”

Parkinson of Glass Door takes a similar stance, also emphasising the need for more supported accommodation. “People with a history of homelessness who do not qualify for social housing or existing supported housing provisions could benefit from transitional accommodation that is equally accessible for those in receipt of benefits, those in employment and those moving between the two,” he says. “We also need enforced minimum standards for properties being marketed in the private rented sector as studio flats, and we need a recognition of the impact of the benefit cap on those reliant on this kind of rented accommodation, especially in London where higher Local Housing Allowance rates can leave tenants with a significantly reduced amount of their Universal Credit to survive on each month.”

In short, landlords and agencies abuse the system because the system allows itself to be abused. Until the government takes meaningful steps to regulate the private sector and provide solutions to people experiencing homelessness rather than problematic short-term fixes, this will not only continue, but get worse. And while it does, the cycle of homelessness will go on, affordable housing will become scarcer, the housing crisis will escalate, and private landlords will – inevitably – keep getting richer.

*Names have been changed to protect identities

Follow Alex Norris on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.