Easing the gay blood ban means more sexual stigma

- Text by Benjamin Weil

- Illustrations by Laurene Boglio

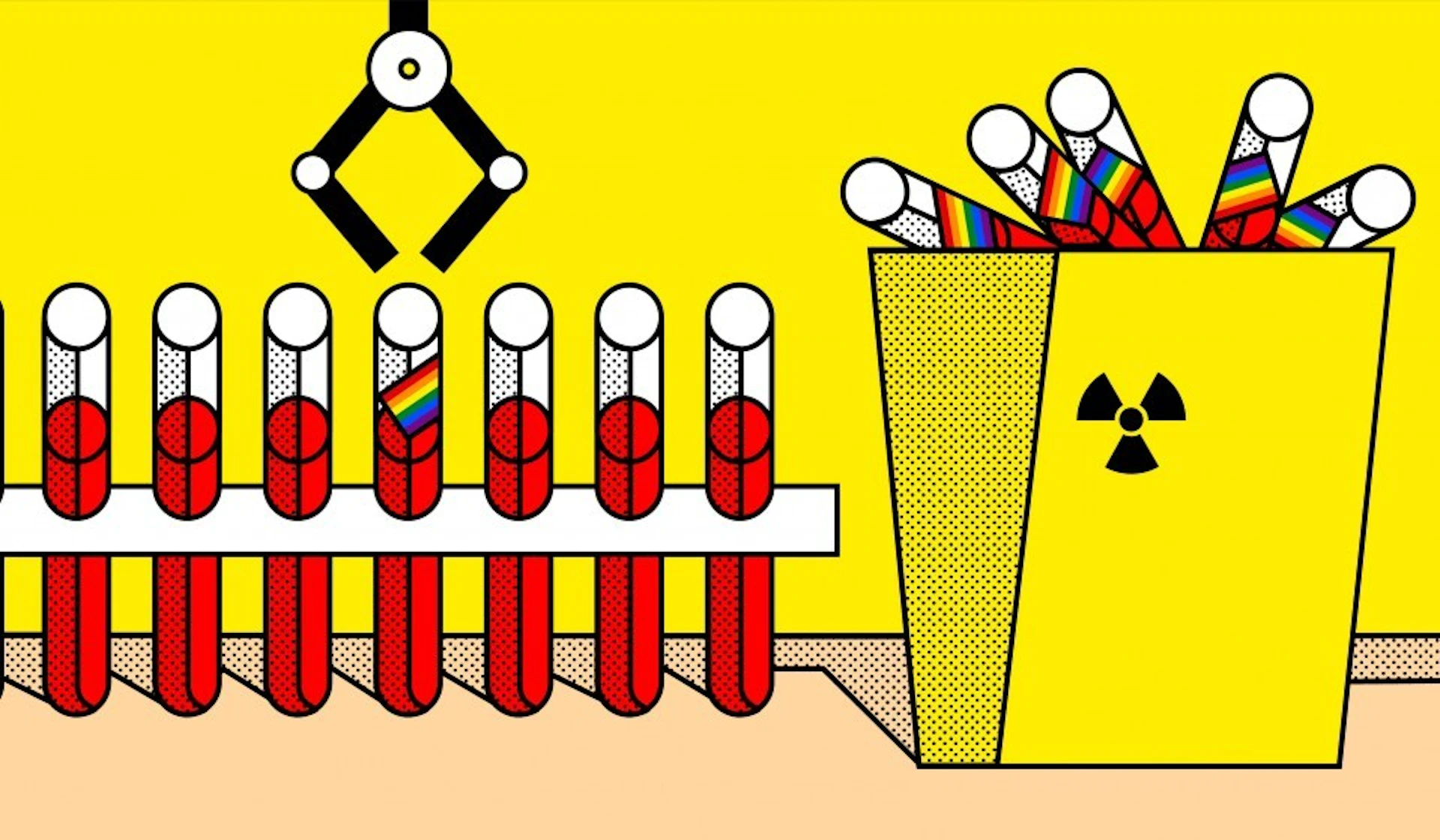

This morning (14 December), Matt Hancock, the Secretary for the Department for Health and Social Care, announced a set of new blood donation criteria that would allow many men who have sex with men (MSM) to donate blood for the first time in England. The change is the outcome of a report conducted by the steering group For the Assessment of Individualised Risk (FAIR), which was formed by the blood services under pressure from blood donor activists lobbying for reform to policies that have historically prevented many gay and bisexual men from giving blood.

The new criteria are set to be introduced in the summer of 2021, replacing the existing policy that prohibits donation from any man who had had any form of anal or oral sex with another man in the past three months. Now, a “gender-netural” policy will permit donation from any individual who tests negative for infection and has had the same sexual partner in the last three months, meaning gay and bisexual men in monogamous relationships will newly be able to give blood.

Many blood donor activists and their supporters have been swift to claim this reform as a victory and a “step in the right direction.” Ethan Spibey, the founder of the blood donor activist group FreedomToDonate and member of FAIR, told Sky News how he felt the new criteria went some way to challenge “the stereotype of a gay man being dirty” that had been etched by MSM deferral criteria since its inception, at the height of HIV/AIDS crisis, in 1983.

I agree with activists like Spibey that broad-brush blood donation criteria, based on purportedly elevated rates of HIV and other transfusion-transmissible infections amongst MSM, unfairly imply queer men to be an infection risk regardless of their sexual practices. But I am also concerned about how eagerly these actors have beckoned in a policy regime that explicitly deems certain other behaviours to be “high-risk practices” in confusing, contradictory and often very troubling terms.

Although monogamous gay and bisexual men are set to be able to give blood in good conscience for the first time in England, ‘individualised’ policy will newly prohibit donation from any individual who has had anal sex with a new sexual partner in the last three months, individuals who use the HIV-prevention tools PrEP or PEP, and individuals who have had a “history of chemsex” in the last three months.

Each of these new criteria – the product of political efforts of blood donor activists to end the tarring of all MSM by the same brush – are troubling in their own right. The FAIR report, for instance, highlights chemsex – vaguely defined as “sex on drugs” or “drug use in a sex context” – as a risk practice because of its links to “other potentially high-risk behaviours such as sex with a person who injects drugs… unprotected anal intercourse… higher numbers of sexual partners, group sex and lower condom use”.

This description of chemsex effects a worrying conflation between what is essentially a very broad spectrum of events – sex parties, threesomes, orgies, mediated by a range of drugs and prophylaxes including condoms and PrEP – and HIV risk. While chemsex might be associated, even in an epidemiologically significant manner, with risk practices, there is no inherent link between chemsex and HIV risk.

In fact, recent evidence suggests that certain individuals who engage in chemsex might be more likely to take up forms of STI prophylaxis than their counterparts who don’t. If we are to seriously commit to the blood donor activist line that policy ought to carefully delineate between risk practices, this must encompass even sexually stigmatised events like chemsex.

The FAIR report also concluded that individuals using the HIV-prevention tool PrEP should continue to be excluded from donating blood. This exclusion has created a set of confusing double messages about the drug, which has only recently been approved for provision by NHS England. While evidence points to the drug being close to 100 per cent effect where preventing an HIV-negative individual becoming infected with HIV via sexual transmission, the exclusion of PrEP users from blood donation will surely create uncertainty around the effectiveness of the drug in preventing transmission at all.

Though the report advocates for the deferral of PrEP users because of lingering uncertainties about whether HIV in their donated blood might remain infectious whilst being otherwise undetectable by testing, this didn’t stop many jumping to a different conclusion.

Today some Twitter users assumed that PrEP users were being (unfairly) excluded on the basis of the link between PrEP use and condomless sex and, therefore, elevated rates of STIs other than HIV. However, the FAIR report makes no such assumption. The fact that such a connection became so quickly propagated evidences what is at stake in the labelling of certain individuals or behaviours as ‘high risk’ or ineligible for blood donation.

In their haste to distance certain (read: monogamous, respectable) gay men from the spectre of HIV with which they have been associated, blood donor activists, in tandem with the blood services, have merely shifted the locus of sexual stigma.

Rather than all men who have sex with men, it is now only the ‘high-risk’ MSM (who uses PrEP, who is promiscuous, who has sex on drugs) who has to carry the burden of HIV/AIDS stigma parcelled out by the blood services. And since exclusion policy is now gender-neutral, even heterosexuals will get to momentarily enjoy the stigma of having gay (anal) sex so that ‘good’ gay men are able to give blood.

Follow Benjamin Weil on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.