Why 'inclusivity' in feminism isn't always a good thing

- Text by Abi Wilkinson

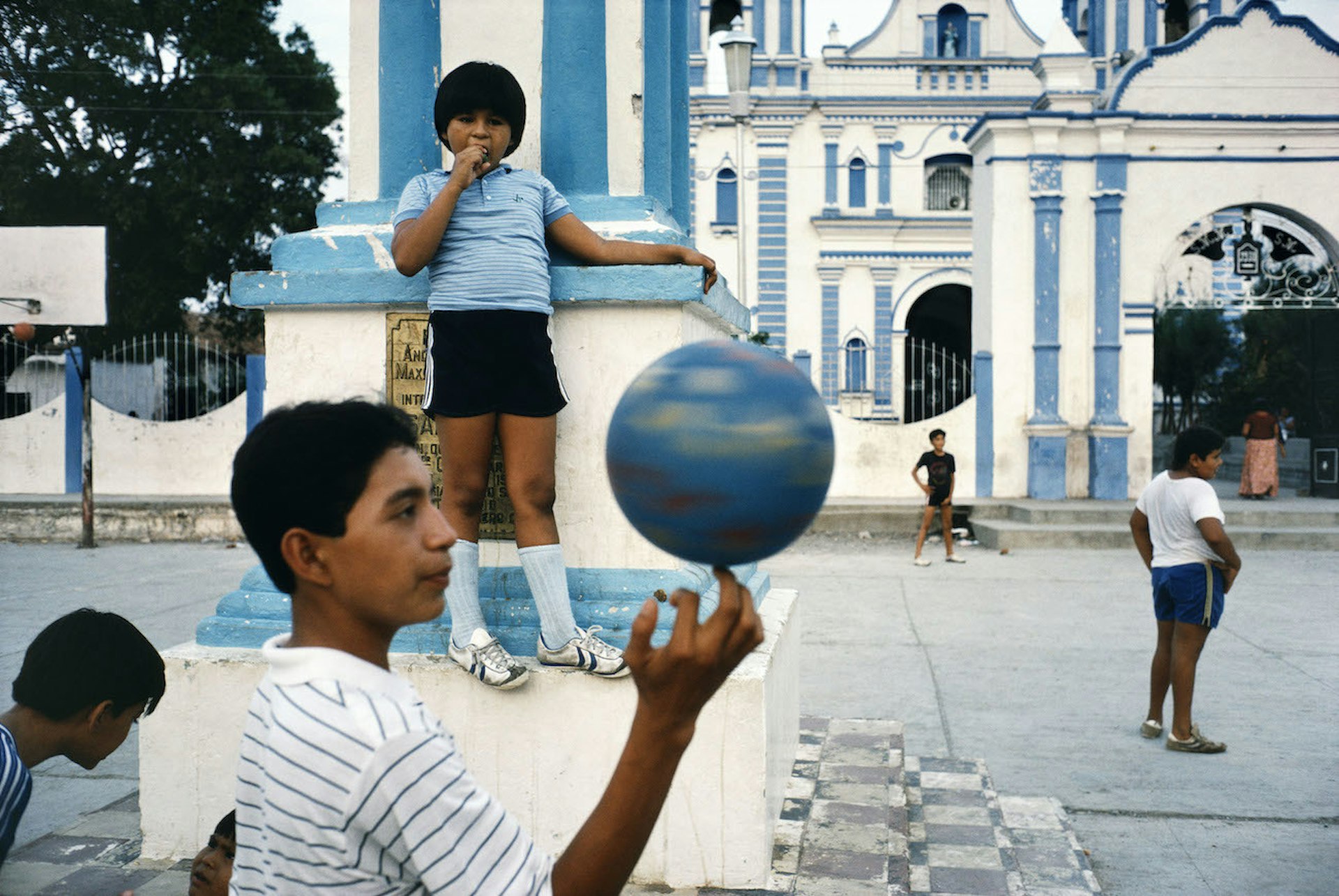

- Photography by via Special K

In 2017, quite a lot of things are supposedly feminist. There are the big ones, like gender pay parity and having women in positions of authority – but you can also make a pro-liberation statement by doing things like “wearing branded activewear whilst doing sports” and “eating cereal”.

Wearing expensive shoes is feminist; having a fuller figure is feminist; being slender, providing it’s what you want to do, is definitely feminist too. Advertisers have discovered that feel-good, feminist messages are an excellent way to sell all kinds of consumer products.

It’s in the interests of these for-profit corporations to make these messages as bland and uncontroversial as possible. In doing so, they can avoid alienating potential customers, but this limits their political usefulness. When “inclusivity” involves placing marginalised women (such as trans women or women of colour) at the centre of a movement, attempting to make feminism more “inclusive” is clearly a good thing. Watering down rhetoric so that almost everyone agrees with it however is a different matter entirely.

If the push to broaden the definition of “feminism” was limited to the world of advertising it might be less damaging; it’s obvious to anyone who’s looking that advertisers alone can’t set the terms of political debate. However, some feminist campaigners have also adopted similar tactics.

After the Women’s March on Washington, there was reasonable debate about whether the pink “pussy hats” worn during the protest were vagina-centric and thus trans exclusionary. Less justifiably, there was also disagreement about whether women who advocate for the criminalisation of abortion should be represented. Though it will come as a surprise to many who marched, organisers even insisted that the protest wasn’t explicitly anti-Trump, presumably in an effort to avoid alienating Republicans.

Some high-profile feminists have gone to great lengths to make men feel welcome in the movement. For columnist and campaigner Caitlin Moran, this involves convincing guys that, when you complain about gendered oppression, you don’t mean them. In an article for Esquire magazine, she suggested: “When women talk about “The Man”, we’re not talking about you. You’re just a man. You’re not The Man. Similarly, when we talk about the patriarchy, that’s not you, either. You’re not the patriarchy. You’re just… Patrick.”

This might be an effective way to get men on side, but it’s a significant departure from how feminists usually understand gender. It’s true that not every man is an active oppressor, but all men passively benefit from male privilege to some extent. What’s more, denying that gender inequality exists between ordinary people makes it harder to fight things like sexual harassment and domestic violence.

In reality, Moran’s point seems to have been about class. “When we’re doing those “MEN!” chats,” she explained. “We’re just identifying the general locus of the problem, i.e., most of the power and influence being held by a small amount of men.” Because mainstream feminism is so focused on the issues affecting class privileged women, it’s possible for the topics to become confused. Yes, the ruling class is disproportionately male – but the way you attempt to fix things depends on what you think the problem is.

The advertiser-friendly version of feminism has a very simple solution: more female elites. Increasingly, the rhetoric of intersectionality has also been incorporated into this project. It’s no longer enough to get more women into senior roles if they’re all white, cis and straight. Your boardroom needs to reflect social diversity in a myriad of ways.

Only one axis of inequality is consistently ignored. Though it’s a central aspect of the original intersectionality framework developed by theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw, campaigning focused on diversifying elites tend to make little mention of social class. In truth, the politics of representation can’t have much to say on this topic because class inequality is intrinsic to the economic system it relies upon.

Pro-capitalist feminism necessarily ignores some of the biggest challenges faced by ordinary women. We’re never going to see a Nike or H&M advert mention that women are disproportionately represented amongst the world’s poor, as doing so would mean acknowledging their own exploitation of (predominately female) sweatshop labour. The celebration of individual wealth and power allowed period underwear entrepreneur Miki Argawal to paint herself as a feminist as she denied employees adequate maternity leave and terrorised her predominantly female workforce.

Feminism that cheers on “successful” women without asking who they’ve trampled on isn’t inclusive in any genuine sense. The interests of economic elites are often directly opposed to those of ordinary people, regardless of gender. A political movement which doesn’t recognise this can’t claim to speak for majority of women, who are disproportionately likely to be in poverty in the UK and across the globe. It’s little more than a branding exercise to shore up the exploitative status quo.

Abi Wilkinson is a freelance journalist based in London writing about politics, inequality, gender, popular culture, and pretty much anything else.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.