It’s time to confront the ‘Karen’ in all of us

- Text by Nathalie Olah

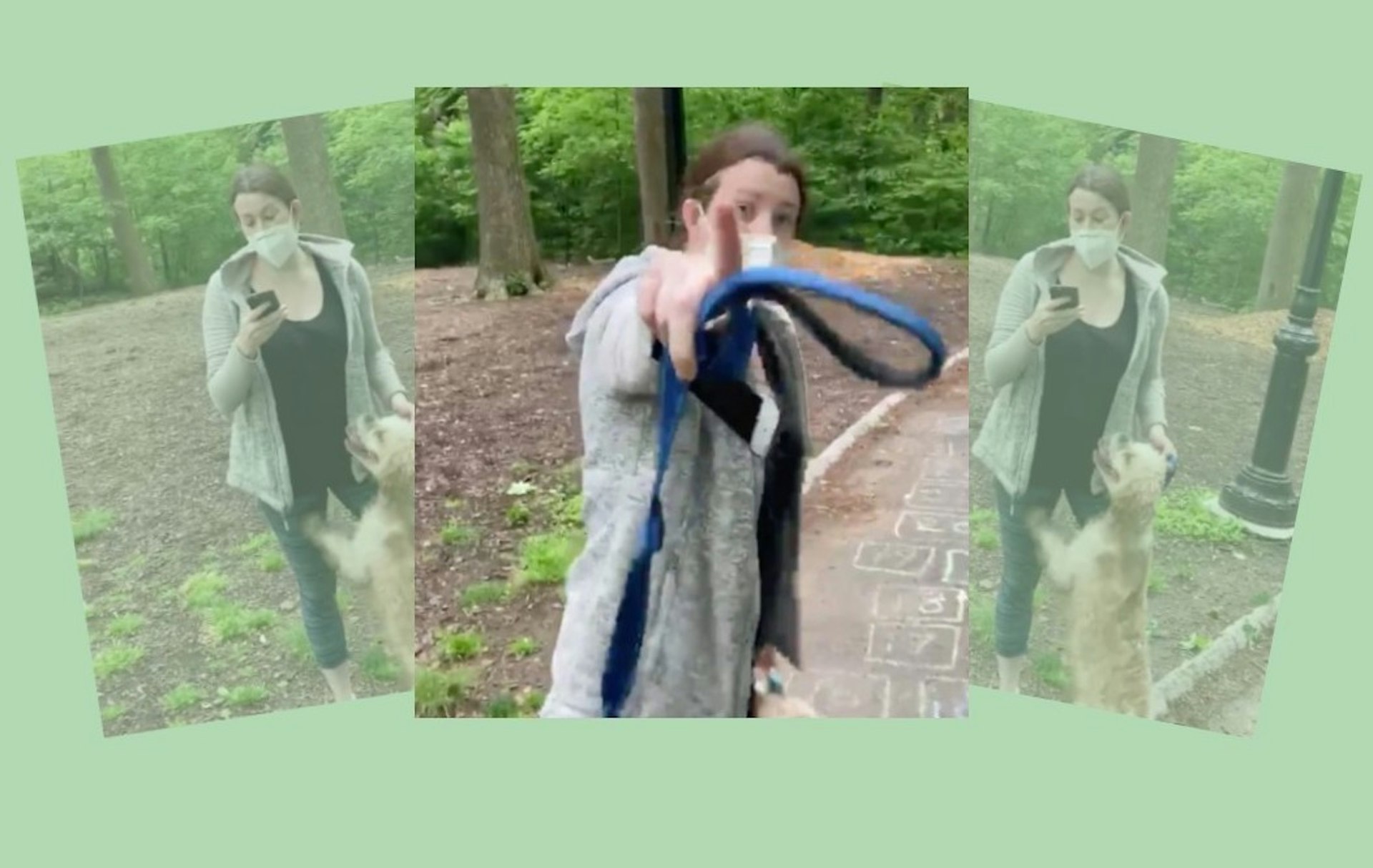

- Photography by Christopher Cooper / Twitter

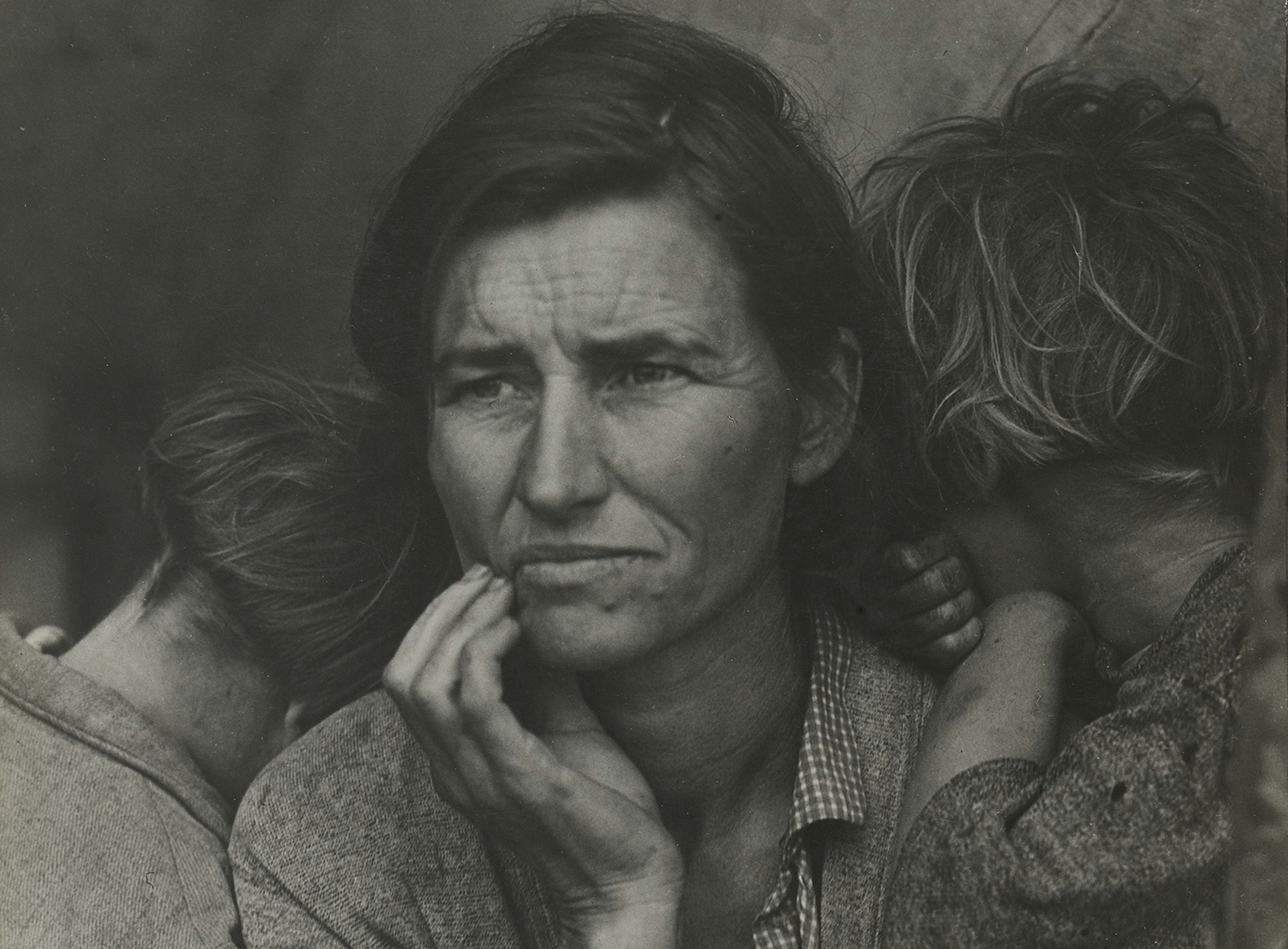

As the war on black people is being waged in America in more vivid and more harrowing terms than at any other point in recent memory, we as white people face a choice: stand up and be counted as allies, or luxuriate in the false sense of our own innocence. Allyship means taking account of our role within in a system of oppression. This doesn’t just refer to the external factors of how we are treated by the police or by our employers, but also addressing the reflexes towards oppression that exist within each of us.

On Monday, and only a few short hours after the killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minnesota, another video appeared online of a white woman verbally abusing a black man in New York’s Central Park. Christian Cooper, an avid bird watcher, asked Amy Cooper (no relation) to keep her dog on a leash in the wooded area of the park known as The Ramble. In response, Amy Cooper called the police to make the false report that an African American man was threatening her and her dog.

This racist lady called the cops on a black man saying he was threatening her life after he just asked her to put her dog on a leash

Her name is Amy Cooper, VP of Investment Solutions at Franklin Templeton

CALL FOR HER FIRING

CALL FOR HER IMMISPONMENT!pic.twitter.com/kex8FNCySE

— StanceGrounded (@_SJPeace_) May 26, 2020

The video justifiably sparked outrage. But if after seeing it the response from white people is still only a sense of disgust towards this awful woman, then we risk missing the point.

In Sister Outsider, Audre Lorde wrote:

It is easier once again for white women to believe the dangerous fantasy that if you are good enough, pretty enough, sweet enough, quiet enough, teach the children to behave, hate the right people, and marry the right men, then you will be allowed to co-exist with patriarchy in relative peace, at least until a man needs your job or the neighbourhood rapist happens along. And true, unless one lives and loves in the trenches it is difficult to remember that the war against dehumanization is ceaseless.

It’s a quotation that has stuck with me over time, reminding me of the Martin Niemöller verse, and the implication that bigotry and discrimination have a way of shifting their targets to eventually encompass all who differ from the dominant group. But in recent weeks I’ve also been thinking about it again, as the perfect encapsulation of a term that has recently been the subject of fierce debate.

For anyone living under a rock, ‘Karen’ is the name being used by predominantly online communities to refer to a haughty white woman whose contempt for service personnel and people of colour leads to a habit of joyfully complaining to the manager or, worse still, the police. In the wake of the Amy Cooper incident, accusations of Karendom were understandably applied. This haughtiness is mixed with enough strategic oversight to know that society’s preferential treatment will allow the Karen recourse to victimhood at the first accusation of bigotry. When Julie Bindel and Hadley Freeman recently argued that the term constitutes a sexist slur, they seem to have fundamentally misunderstood the nature of sexism. When white tears are weaponised against a black woman, it is the white person, regardless of gender, who is enacting the patriarchy.

But in Cooper’s case, the tears hadn’t worked. This felt like a watershed moment in exposing the more ‘respectable’ forms of racism that continue to fly under the radar of quiet society. Amy Cooper is an investment banker with a degree from the University of Chicago. If, as she claims, the event in Central Park was an ‘over-reaction’ and the first and only time that she had ever made such remark in public, then it’s safe to assume that racist comments were still enjoyed a free pass at home.

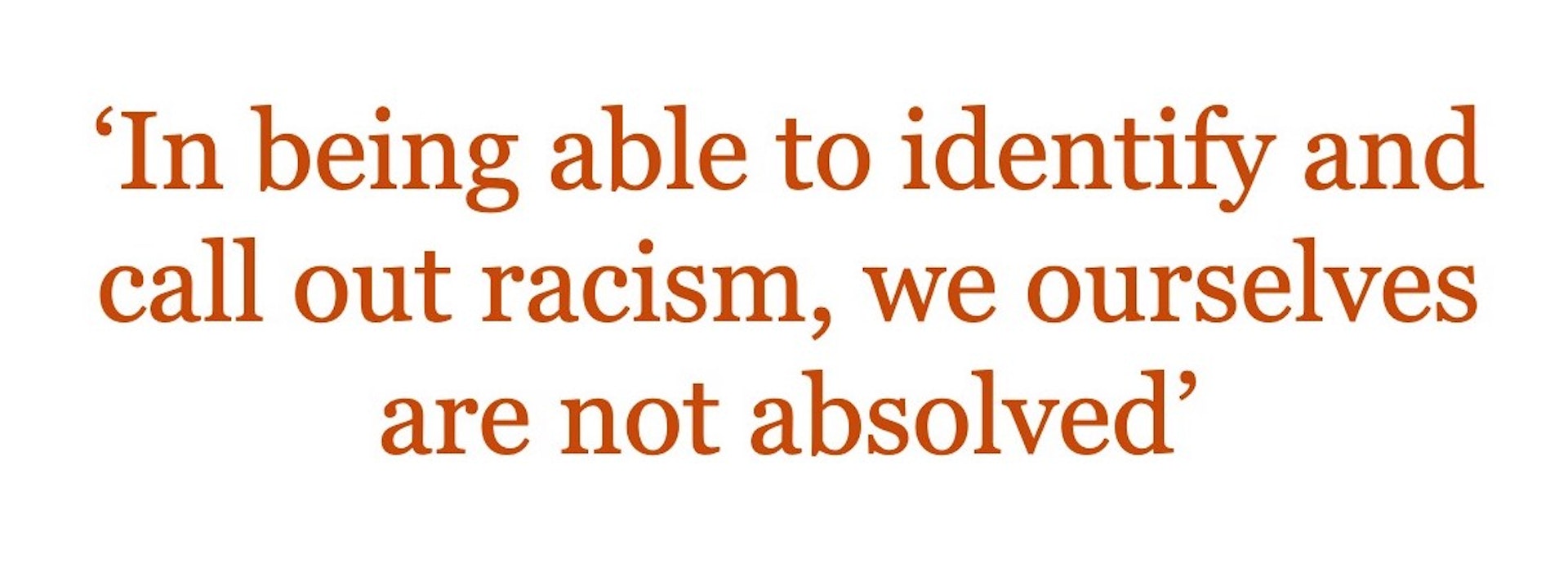

I’ve faced a difficulty in knowing how to frame my criticism of Cooper. On the one hand, I know that I would never do or say the things that she had done and would never challenge the right of anyone to correct me if I was in the wrong. I certainly wouldn’t feel the urge to avenge my own embarrassment by summoning the language of mob violence and lynching. But like every white person on the planet, I had undoubtedly at times engaged with the dangerous fantasy that provided I was ok and out of danger, all was well with the world. This goes for calling out instances of racism as well. In being able to identify and call out the bad thing, we ourselves are not absolved.

It’s quite possible for the dangerous fantasy to also coexist with the urge to donate, tweet, post on Instagram and talk endlessly about the importance of black lives. We must all continue to donate, but the other gestures of solidarity are meaningless if we’re not going become more vigilant – even militant – in our own lives and with respect to our communities. There can be no more quietly minding our own business, working for institutions that have historically undervalued and under-represented people of colour, adhering to bosses who have treated us preferentially over black candidates who were never hired, or colleagues who are perennially kept at a lower rank. We can’t just roll our eyes at racist relatives, or turn awkwardly from the person racially abusing someone in public. We can’t just smile sweetly through stark inequality – enjoying the spoils of our lives while millions are being discriminated against violently – while occasionally registering our support for ‘the black community’ with the occasional nod to an NTS radio show playing world music.

Have I ever got frustrated at a call-centre worker who was probably, also, a person of colour, or accepted work from companies whose track record on racial diversity was pitiful? Did I fancy the boy at school who made occasional racist jokes, despite how it made my best friend feel, whose parents were Nigerian? Have I done things in day-to-day life that make quiet, subconscious assumptions about my own superiority, and which inadvertently undermine or humiliate people who are not white? The answer is yes, by fact of being white. And hard as that is to swallow, and humiliating and shameful to admit, it pales in comparison to the onslaught faced by millions of people every single day for whom the stakes are life and death.

The least we can do as allies, in addition to donating to charities protecting black lives, is be graceful in admitting our place in a system of oppression, and not baulk at the mere suggestion that we might be in some way complicit, albeit subconsciously, or unintentionally. This is key to achieving the hyper-vigilance that will be required of the vast and all-encompassing struggle against racial oppression in our society. It is important not to fall into the trap of thinking that racism happens elsewhere and there is a gesture of humility necessary from all of us, to accept that many of these reflexes have been instilled in us since birth, and that we all have a job to personally address them.

That does not mean that we must shy away from acts of solidarity – quite the opposite. We must extend that solidarity to the act of holding ourselves and our white neighbours and friends to account. Because someone somewhere knew that Amy Cooper held these views, and if they’d only challenged her on them sooner, a black man might have been spared an afternoon of fear and humiliation, and she might still have a job.

Follow Nathalie Olah on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.