Stop calling Jeremy Corbyn an IRA terrorist sympathiser, it's simply not true

- Text by James Butler

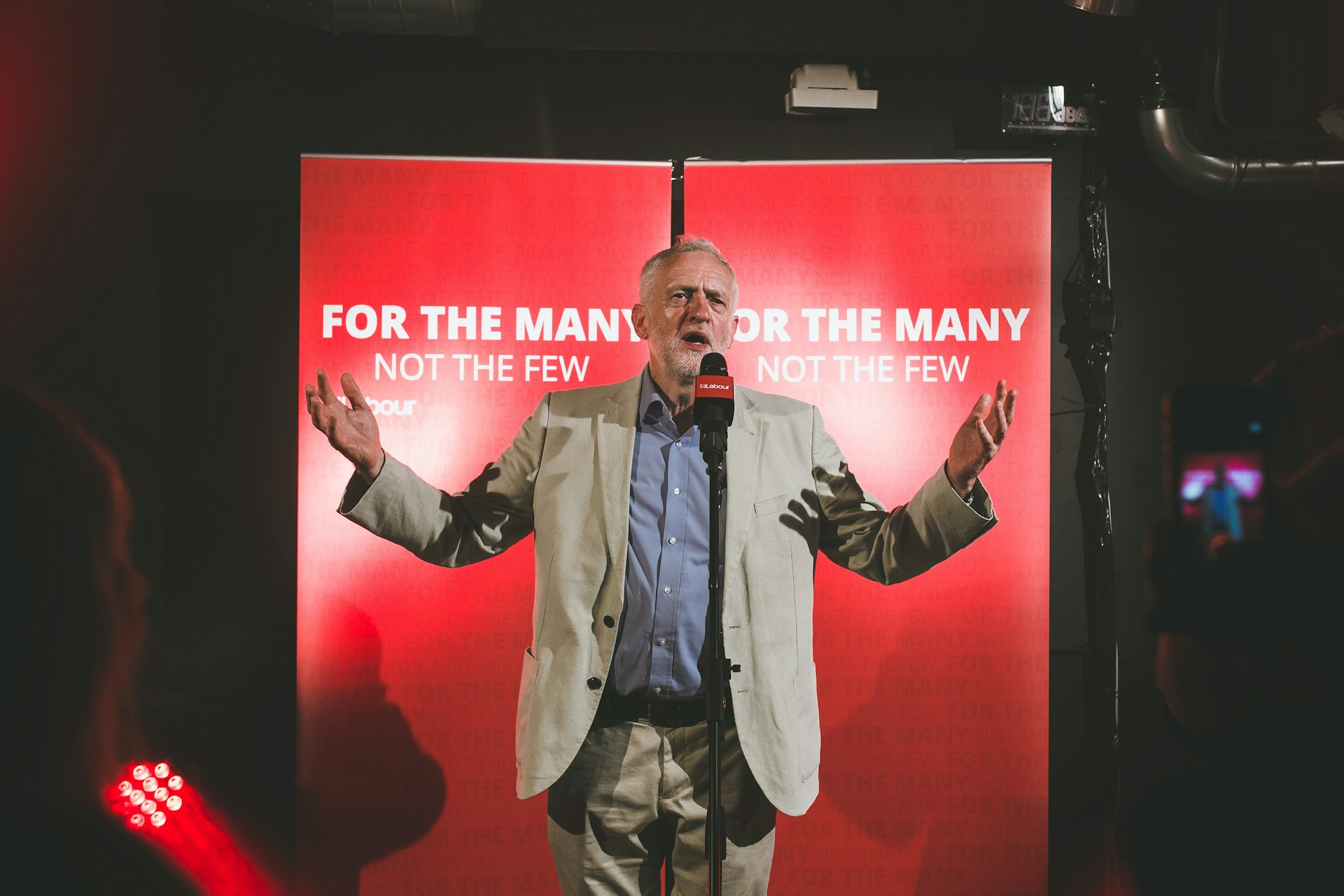

- Photography by Theo McInnes

When Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour leader back in September 2015, conventional wisdom suggested that his past associations with Irish Republicans – including invitations he gave to Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams to visit Westminster in the 1990s – would be used to hammer him in a national campaign and eventually spell his downfall.

Both the press and the Tory party have revived such attacks in the past weeks, though to less avail than expected. Without any new revelations, they have had less purchase than might be expected, but it is likely the Tories will keep running them to shore up their base’s hatred of the increasingly popular Labour leader.

So what is the truth? Many of those attacking Corbyn do so with a hefty dose of condescension to his younger supporters, deeming anyone under the age of 30 incapable of understanding the severity and danger of the IRA’s bombing campaign, nor the sense of betrayal felt by its victims at Corbyn’s fraternisation with Republican leaders. Certainly my own memories are a compound of images of the 1996 Manchester bombing with folk myths about not standing too close to bins in central London, and Gerry Adams’ words on the news.

But England’s perception of its war in Ireland (Patrick Keiller’s phrase, subversive in insisting the English take some ownership of it) has always been shrouded with myth, not least the myth of inexplicability. It attracts its inevitable share of armchair extremists, not all on the left: it was Michael Gove who called the Good Friday Agreement – the 1998 peace and power-sharing agreement now governing the north – ‘a mortal stain’, a ‘humiliation’ for the British army. Jeremy Corbyn voted for it.

Litigating past sins, alleged or real, is an ugly business, but if we are to revisit the past then we should do so properly, not least by correcting the vacuum which is Ireland in English historical and political knowledge. At the very least, that involves understanding the profoundly unequal social conditions in the north in the years between 1922 and the formation of the Provisional IRA in 1969: that included effectively segregated housing, and an electoral system which advantaged a Protestant minority by making votes conditional on property ownership and offering multiple votes to business-owners; the clearest index of this inequality was unemployment, which affected Catholic youth in huge disproportion.

The Special Powers Act, ‘emergency’ legislation which became permanent, gave authorities the power to intern without trial those suspected of disturbing the peace. In practice these powers were used almost exclusively against Republicans.

The entanglement of the British state with Loyalist paramilitaries, the open question of whether the RUC – the north’s notoriously corrupt and violent police force – operated a covert and illegal shoot-to-kill policy against suspect IRA members, the sheer obstinacy of Downing Street under Thatcher: these matters troubled English consciences too little, and are too easily passed over.

It is worth remembering especially Thatcher’s fatuous insistence that the IRA – and the Troubles in general – were merely misdirection for criminal enterprise; her tasteless posturing in the Commons after hunger striker Bobby Sands’ death – ‘a convicted criminal’ – succeeded in generating only a sneaking sympathy for Sinn Féin and even the IRA where little had taken root before.

None of which is to say, either, that the IRA didn’t demand support with violence in its own communities, nor that its war of attrition could be ‘justified’ by a particular quantum of British violence, but that to treat the IRA as the sole engine of the conflict – as interviewers have tried occasionally to make Corbyn do – is historical idiocy.

Is it possible, however, that the English hard left occasionally found itself overcome by a romantic picture of Republicanism? Certainly. But it is equally fatuous to say that any peace could have been brokered without the IRA: indeed, at the time the peace process truly got underway, one such torpid effort (initiated by then Tory MP Peter Brooke) had been drifting along uselessly since 1991. Republican participation would set off a crisis of Unionist faith and mistrust, fearful its hegemony would be troubled by a no-longer credible ‘enemy within’; Ian Paisley, the Unionist hardliner and Protestant fundamentalist, was master of this tactic.

Certainly, though, the English hard left’s story about Republican successes is sometimes rosy and simplistic. It’s true that the dual strategy – bullet and ballot-box – led to Sinn Féin’s sudden success in the 1983 elections, displacing the constitutional-nationalist SDLP from its sole position as politically ‘legitimate’ voices for a united Ireland; this electoral position would eventually become the pretext for Sinn Féin’s involvement in the peace process. What is frequently left out, however, is that it was the slow and patient work of the SDLP’s John Hume which would eventually provide Gerry Adams with the political framing sufficient to turn the Republican movement away from the dead end of the paramilitary campaign.

The charges against Corbyn are often overinflated: they amount to a solidarity with Irish independence common to the left at the time, a claimed position on the editorial board of Labour Briefing, a magazine which rather tastelessly joked about the Brighton bombing, and invitations of Republican leaders to Westminster and too close an association with them. Taken together, these are used to suggest that Corbyn either approved of the IRA’s bombing and armed struggle, or effectively had no problem with it, and that his statements to the contrary are presented as either lies or self-delusions. There can be no serious claim that Corbyn endorsed or supported IRA violence at the time: no such evidence exists.

The more reasonable version of this claim runs thus: that Corbyn was either too romantic or sentimental about the Republican movement, too trusting of its claims to want only peace, and too lax on connections between the political and armed wings of the movement.

It amounts less to a political endorsement of terrorism than a question of his political judgement. I don’t wish to defend every choice Corbyn made in this period: it would be strange if among the Sinn Féin members he met there were no active IRA members, and certainly the timing of his invitation to Adams after the Brighton bomb was crass. Yet, however unpalatable, it is unquestionably true that Corbyn’s pursuit of dialogue with Republicans, rather than ever harsher war, correctly anticipated the only choice which could lead to peace.

Defences of Corbyn are sometimes overinflated as well: Corbyn’s meetings with Republicans were ancillary to the later real and substantial peace negotiations. But objection to his position often conceals a deeper suspicion that he is fundamentally hostile to the idea that the British state, ultimately, is in the right – whatever its atrocities. This is why his calm insistence that Loyalist and British military brutalities always be condemned alongside IRA violence infuriates those who would, in the end, seek to exculpate the British state.

It is the same attitude which dredges up Diane Abbott’s history of pointing out the deeply-lodged institutional racism: the ‘my country right or wrong’ brigade, who believe that assessment of a country’s failings and complicities is tantamount to treason. It is the same attitude which imperilled the peace process in its fragile beginnings.

If Corbyn’s views during the Troubles were sometimes too forgiving of Republican misdeeds, then his consistent position throughout, that peace would come of dialogue and the fostering of mutual solidarity, rather than unceasing war, was eventually proven right. That attitude, which refuses narrow jingoism, and understands why terrorism happens – without seeking to forgive or excuse it – is the only permanent route out of conflict. It’s a sentiment he holds true to today, his speech following the this month’s Manchester bombing was based on the exact same premise, and the majority of the British public agree.

In a time where state abuses of power over terrorism are rife, a man whose campaigning as an MP focused especially on the miscarriages of justice and state-led abuses (the Birmingham Six, Guildford Four, the multitude of statute-led abuses permitted by 1974’s Prevention of Terrorism Act) should be seen as a real political asset.

And with Brexit now putting the Irish border back on the political agenda, I would far sooner see a politician in office who seeks to understand all sides, possessed of an unwavering belief in the power of dialogue and negotiation to solve political ills, than an authoritarian PM who believes the border issue will vanish by mere wishing.

James Butler is a writer and editor at Novara Media based in London. Follow him on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.