Even £50 million won’t make a new centrist party relevant

- Text by Matt Zarb-Cousin

- Illustrations by Sophie Mo

A new party is on the march. It’s not quite Macron’s En Marche!, but the good news is we may no longer have to endure despairing tomes about the “politically homeless” more often than we hear complaints about actual homelessness. These moans are, almost exclusively, from centrist dad types – those middle aged Blairites who haven’t quite come to terms with the changing world yet.

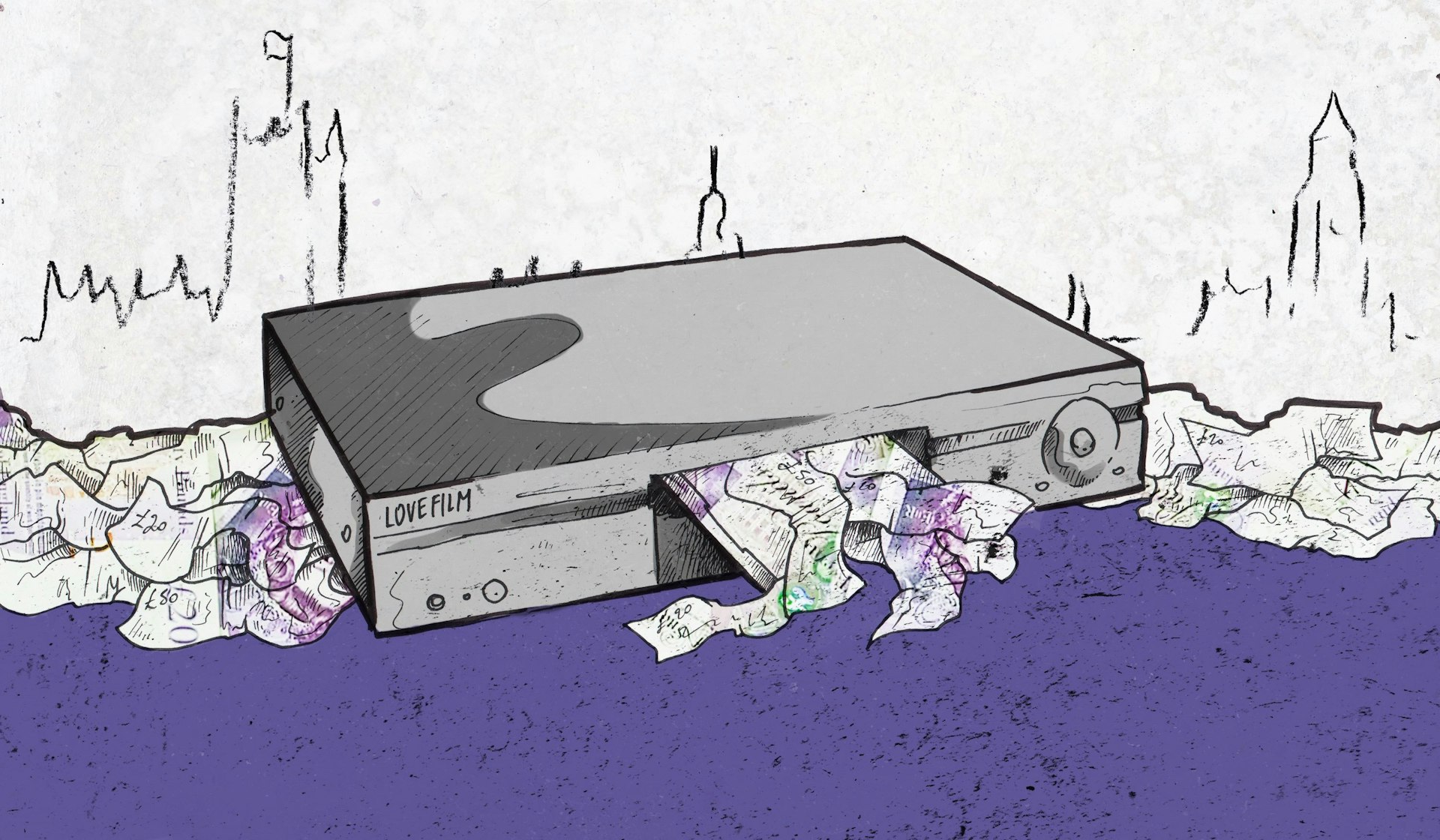

This weekend, The Observer’s front page carried the news that Simon Franks, the founder of DVD rental service LoveFilm, is in the process of establishing a new party of the centre in Britain. It’s reported to be backed by senior figures from business, including some Conservative donors – although no other names were mentioned in reports.

We’re told it will be aimed at a liberal, centre left audience, but that it would also “support centre right ideas on wealth creation”. A socially liberal, fiscally conservative party. So you might say they know the problems in society are bad, but they believe the economic causes to be… very good.

Essentially this new party is a rebrand of the Liberal Democrats, but instead of coming with the baggage of having propped up a Conservative government, it’ll itself be propped up by Conservative and corporate donors, who want to prevent a transformative Labour Party led by Jeremy Corbyn taking office.

It’s fitting that a centrist party aiming to maintain or, at best, slightly ameliorate the status quo – appealing to those Liberal types who only avoid voting Conservative because they feel guilty about it, and who don’t agree with Brexit anyway – is the brainchild of LoveFilm’s founder Simon Franks. Because a business which asked people to post rented DVDs back instead of physically returning them to a shop is actually analogous to centrism. It doesn’t ask fundamental questions about the purpose of renting a physical DVD, or consider how DVD renting isn’t really a thing of the future. It just tries to slightly improve the process of renting a DVD. And then it becomes irrelevant.

If Franks set out to cut through to people with the so called ‘Project One Movement’, then he succeeded. We’re talking about it, and that’s the objective of marketing above all else, he might argue. If your only conception of politics is through the prism of the media, you might be forgiven for thinking that there isn’t much to it. Just come up with a name, a broad set of “values”, get on the front page a national Sunday paper by revealing the £50m war-chest backing you, and hey presto – you’re in the game.

But politics isn’t anything like marketing a brand. You can’t simply rock up with a broad set of values akin to that of a corporation, along with a rough idea of what you’ll do or where you fit on the political spectrum, and expect people to buy into it.

Being a known “brand” is not enough, you have to demonstrate, through policies that are reflective of and reinforce your values, how you’d improve people’s lives. You have to recruit thousands of activists who share your vision, and you have to come up with a plan to navigate an electoral system built for two-party politics. So why the decision was taken to tell the press how much corporate cash was backing the Project One Movement before any work had been done on actual policies is anyone’s guess.

It looks like Franks weighed up the pros and cons, and decided that marketing his initiative was more important than the political consequences.

In an era where anti-establishment sentiment is sweeping across the world, when the top 1% is on track to own two-thirds of the world’s wealth by 2030, leading with how many corporations and entrepreneurs are backing you is probably politically unwise – unless you want to be nicknamed “Project One Percent”.

The prospect of a well-funded centrist party that doesn’t threaten to challenge the status quo, that accepts an economic settlement predicated on Thatcherism, is surely likely to appeal to Conservative voters more than Labour supporters, as well as posing existential questions about the future of the Lib Dems.

When the “gang of four” Labour MPs broke away from their party to form the SDP back in 1981, they entered into an alliance with the Liberal Party. Without a similar alliance with the Liberal Democrats, Project One risks splitting the liberal vote. That said, a pact with the electorally toxic Lib Dems will only draw criticism that they’re simply Lib Dem Lite. So it’s surely doomed either way.

Meanwhile the Labour Party continues to explore the possibility of democratising Parliamentary selections, so candidates are accountable to activists who give up their time and money to help get them elected. There are a few dozen Labour MPs who have made it their mission to undermine Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, and it’s certainly possible that these MPs might think that if they’re going to get deselected anyway, then they might as well defect.

Except, the relevance of these Blairite rebels is tied to their status as dissenting Labour MPs. A story propagating Labour’s internal war is far more newsworthy than an MP of a party no one will have voted for attacking Jeremy Corbyn. By defecting to Project One, they’d blunt their attacks, leaving a united Labour Party in Parliament.

The expense of electoral competition from another pro-establishment party, by the rich and for the rich, is a small price to pay for that. But it’s a sad indictment of the economic elite in Britain that they cannot get behind the social democratic platform offered by the Labour Party at the last election – one that reflects the real centre ground of public opinion.

So this initiative is more an attempt to preserve the economic interests of an elite than to fill a meaningful gap in the political spectrum. But it’s a poor one at that. Without policies or a popular movement to go with it, it’s reduced to the vanity project of the anonymous, super rich. If they really cared about helping make society a fairer place, you’d think they could find a better cause to make use of all their cash.

Follow Matt Zarb-Cousin in Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.