Battling depression and addiction at London’s homeless boxing club

- Text by Matt Broomfield

- Photography by Giulia Fassone

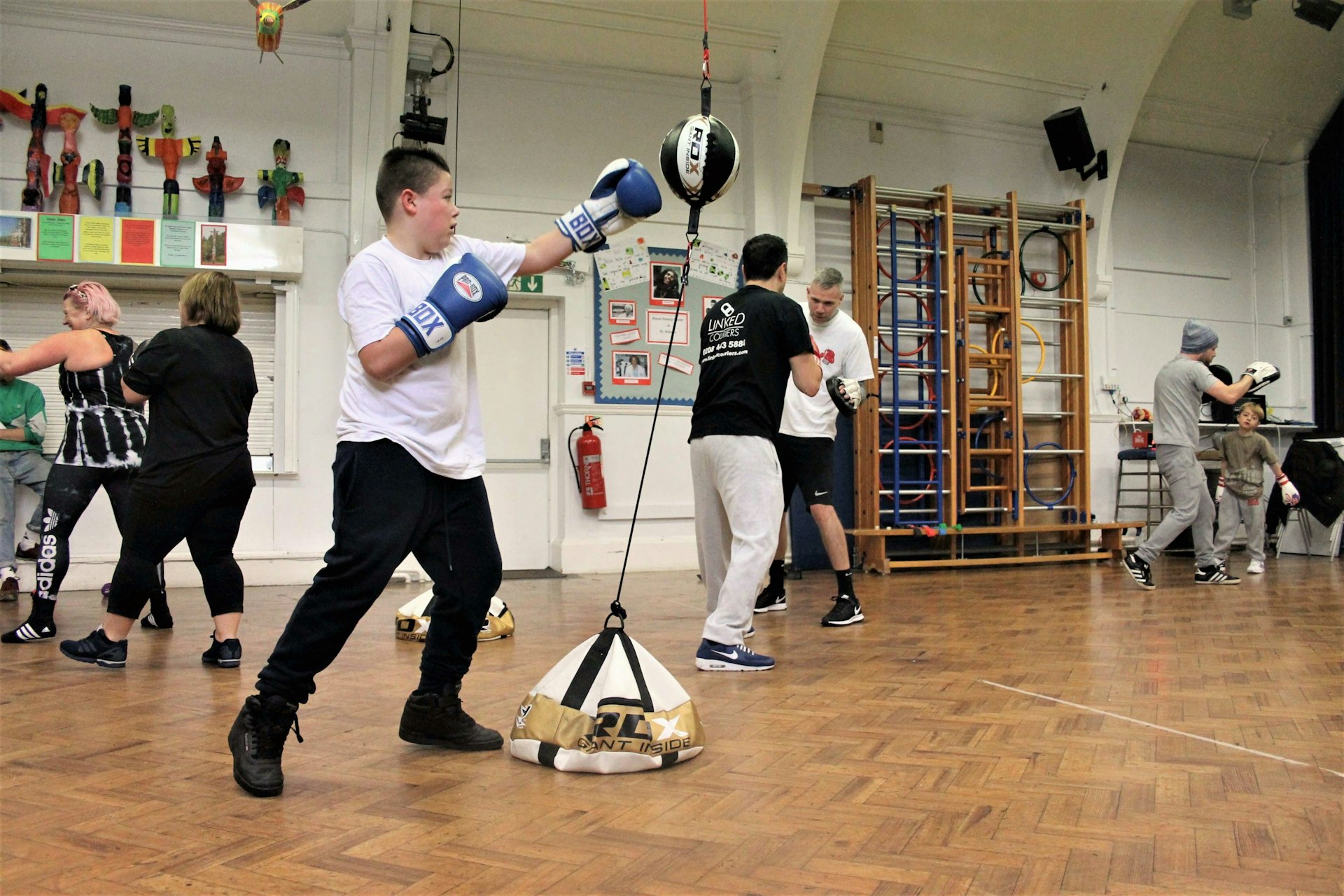

A scrawny preteen bounces on his tip-toes to batter a muscle-bound former boxing champion with a volley of jabs: a single mother leathers a punching-bag under the close supervision of a recovering crack addict.

Sam Hadfield, the founder of the UK’s only boxing club for the homeless, watches over his gasping protégés with a grin. “These people aren’t looking for a world title belt,” he says. “They’re looking for a place back in the world.”

This Sunday morning sparring session is taking place in a North London primary school hall, below papier-mâché storks and sugar-paper dreamcatchers, amid a distant yet lingering aroma of Turkey Twizzlers.

Sam

In flat cap and knuckle tats, 53-year-old Sam looks like a cockney Santa, and he enters the room a tumble of punched arms and belly laughs. “We’ve got a reporter here, so best behaviour, everyone. You’re not wanted by the police, are you?” he adds, addressing a hyperactive ten-year-old who’s busy pummelling a punching bag.

“I’ve been doing this for six years, but it still kills me when I see people struggling,” Sam explains, as the crowd of 20 or so break up and begin chucking air punches.

Following a heart-attack the best part of a decade ago, depression had him “locked away”. This crisis led Sam to volunteer with rough sleepers as a way of getting stuck back into day-to-day life, and now he works with Caris, a homeless shelter in Islington.

“These lads were just sitting there on a Playstation,” says the lifelong boxing fanatic, who also works as a caretaker. “So I brought in gloves and pads, and they were loving it.” Six years later, and the Caris Boxing Club has seen scores of North London’s most vulnerable come through its doors – and some of its most famous.

“We were in the press last year when Jeremy Corbyn came to visit,” continues Sam. “But I’m not doing celebrity visits anymore. That’s not who the real champions are.”

As far as Sam sees it, the spotlight should be on people like Amy, a 30-year-old mother of three just starting out at Caris.

“My dad died when I was seven,” Amy explains. “Heroin. I’ve been ill since I was 11, self-harming, my own addiction issues… But I’m still here now. My son Lee over there is 10 and he’s seen violence from my partner, he’s seen me off-the-scale drunk.”

To Amy, the boxing club provides a chance for some much need to one with time with her son, “getting both of our aggression out”, she adds. Punching away, she explains that if it wasn’t for Caris, she’d spend Sunday morning lounging around drunk or hungover in her pyjamas.

To be fair, she’s probably not in a minority in that respect. “But if I didn’t have this place I’d have no incentive”, she continues. “Someone putting their hand out and saying ‘Amy, we’ve got faith’… it’s never happened before.”

Though Caris describes itself as a club for the homeless, Sam and his coaches are at pains to emphasise that “no-one’s ever turned away”.

But Some boxers here are very much living on the street. A Lithuanian guy known as Harris was a rough sleeper when he first joined the club, but having made himself a regular he was put through an Amateur Boxing Association training course, securing his coaching credentials. Now he runs his own boxercise classes elsewhere in the capital.

But many more are simply vulnerable: most are living with addiction, and all have the ropy mental health of the long-marginalised.

Pete (left) and Danny (right)

“I was destroying myself, killing myself,” says Pete bluntly, whose bad back is keeping him to the sidelines of the work-out session. He’s 48 now, but years of drug abuse have added a decade of lines to his face. “When you’re an addict you’re isolated, you think you’re on your own.”

“So it’s not just the training: it’s being with people who speak the same language”, he tells me. “There’s no hierarchy, everyone’s here as themselves. I’ve been part of the furniture here for years.” Pete has been clean for a year.

More than 8,000 people slept rough on London’s streets during 2015/16, a figure that’s more than doubled in the last five years, and nearly tripled in a decade. Even on the short route from the tube station to the primary school, I pass homeless people bundled asleep in a dank and damp underpass. It’s a pattern that stretches across the city.

But with 380,000 people living in ‘hidden homelessness’ across the UK, there is an invisible crisis too. Based for years in squats and hostels or surfing sofas, the hidden homeless are vulnerable to eviction at a moment’s notice, and often lack the structure needed to combat substance abuse or mental health issues. (London is also the most crack-addicted city in the UK.)

In whispery tones, Pete’s mate Danny explains the difficulties he faces, even as someone fortunate enough to have a flat of his own: “I know I’ve got to go back to an empty house. I brought up my three kids as a single dad, but they all went off and they ain’t coming back.”

“I used to care for my disabled dad but since he died, I’ve got nothing, no-one”, he says quietly. “I was alone over Christmas and I was thinking [about] suicide.”

Maj

Instead, the 54-year-old returned to the ring. “You hit the bag and it takes a weight off”, he says, picking up the pace. “I used to box years ago, so it’s nice to see people picking it up.” He turns to a woman catching her breath beside him. “Maj couldn’t get the footwork today, but that hook…” they both mime a vicious swipe, and break out into laughter.

Maj, 44, describes herself as a willing punching-bag in the name of gender equality. “If it’s all men it’s a bit off-putting, and the men don’t really want to hit you. But with me here?” she bumps her gloves together: “It’s a fair match-up.”

Sam wants to make the club as inclusive as possible, not just to men and women alike but for at-risk kids too. Treating them equally to the adult boxers, he shows them the respect – and demands the maturity – they are denied elsewhere.

“I just won a bet with Mickey over there,” he says smiling, pointing to a wiry kid throwing electric combos of jabs. “I told him I’d give him 50 quid if he could go a month without getting excluded from his special unit at school. Of course, he couldn’t do it.”

Mickey

“But don’t put that in your article, we’re all clean-living here,” chimes in Mickey’s dad wandering over for a cigarette. Cash betting might not be an OFSTED-approved teaching method, but Chad, 43, reckons he was glad to see his son getting some positive male mentorship.

“I want my boy to do well,” he adds. “I know what it’s like on street corners, with the fucking gangs.”

Chad himself went from a “big boxing past” as a schoolboy champion to the depths of a grand-a-week drug addiction. Five years clean, he now helps Sam to lead the sessions, loping round the hall and stretching the reach of the club’s hottest prospects.

Watching the sparring session, it’s difficult to tell who’s homeless, who’s battling addiction, and who is simply there to help out. And these divisions don’t mean much to Sam or his fellow coaches; caked in sweat and struggling through sit-ups, well-meaning local parents are indistinguishable from addicts and rough sleepers.

On the street these people might be marked out as anti-social, counter-cultural, dirty, unsafe: here, they’re standing up and fighting back.

The names of under-18s have been changed.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.